|

Studio Ghibli is one of the few animation production houses whose name is internationally known outside of industry circles, a badge of quality that carries with it specific expectations for style and storytelling. Initially, all of its films were directed by two of its co-founders, Miyazaki Hayao and Takahata Isao, though one of its most celebrated and standard-setting works, Miyazaki's 1984 Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind [Kaze no tani no Naushika], was made a year before studio's formation so is technically not a Ghibli film at all, despite its regular appearance in Ghibli DVD collections worldwide.

The studio's international reputation was secured largely on the back of Miyazaki's thematically complex and richly imaginative fantasy works such as Castle in the Sky [Tenkū no Shiro Rapyuta], Kiki's Delivery Service [Majo no Takkyūbin], Porco Rosso [Kurenai no Buta], Princess Mononoke [Mononoke-hime], the Oscar-winning Spirited Away [Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi], and the glorious My Neighbour Totoro [Tonari no Totoro], whose title character became the studio's logo. Being reality rather than fantasy based, Isao's work is less widely seen outside of Japan, but that didn't stop his 1988 Grave of the Fireflies [Hotaru no Haka] from finding a small but passionate international audience. If you've never seen it then I implore you to hunt it out – it is, quite simply, the most emotionally devastating animated film I've ever seen. Less traumatic but every bit as involving is his 1991 Only Yesterday [Omohide Poro Poro], a simple but bewitching story of an unmarried career woman who returns to her rural roots and rediscovers her childhood self, one whose realism, sense of place and attention to detail delighted a Japanese friend of mine who grew up in just such a district and has infrequently embarked on her own journeys into the rural past.

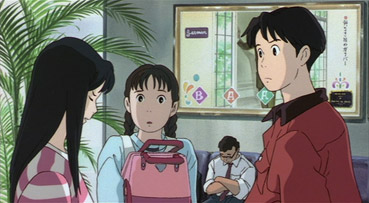

The 1993 Ocean Waves [Umi ga Kikoeru] was the first Ghibli film not directed by either Miyazaki or Isao, and the studio's first film produced specifically for television. Based on the novel by Himuro Saeko, the film was made almost exclusively by the studio's younger staff members under the direction of the then 34-year-old Mochizuki Tomomi, their aim being to produce the film "quickly, cheaply and with quality," which apparently didn't stop it from going over budget and missing it's planned completion date. Like Only Yesterday, the storyline itself is deceptively straightforward, a gentle coming-of-age tale told from the perspective of high school graduate Taku, who is returning to his home town of Kōchi in Shikoku for a class reunion. As he travels, he recalls his friendship with fellow student Yutaka and the arrival of high-achieving but temperamental new girl Rikako, who has transfered from Tōkyō and with whom Yutaka quickly becomes enamoured. When Rikako borrows money from Taku on a school trip to Hawaii, it has a knock-on effect that later sees him inadvertently accompany her to visit her father in Tōkyō, a trip that puts his friendship with Yutaka in jeopardy.

I have little doubt that as a UK or US-made live-action piece, Ocean Waves would have played out as a box-ticking love triangle drama built around Taku's awaking passion for Rikako and his resultant conflict with Yutaka. But there's an honesty and simplicity to the more personalised approach here that is both refreshing and disarmingly easy to relate to, as during the transition from youthful innocence to a more adult awareness, actions are misinterpreted, signals are misunderstood, and the behaviour of others proves confusing. Rikako in particular is a source of constant bemusement for Taku, her fickle nature and sudden mood swings leaving him uncertain just where he stands from one minute to the next. Her seemingly schizophrenic attitude towards him peaks when he offers to accompany her to Tōkyō and is bounced between roles in the blink of a whim. The subjective approach assures that we share his frustration as he is alternately embraced and ignored, introduced as her boyfriend when her image requires it and her first port of call when things don't work out with dad, but irritably tossed from the bathroom in which he has chivalrously slept so that she can keep a date with an old flame the following morning.

It's to the film's considerable merit that no clear reason is provided for Rikako's behaviour beyond the frustrations resulting from her parents' divorce – she's simply as moody, self-centred and unpredictable as everyone of the opposite sex seemed to be when we too were young enough to get away with behaving likewise. And it's here that the film is able to effortlessly connect to an international audience, to enable them to get past the localised elements of regional accents and the seemingly random swapping between forename and surname, and recognise in Taku's irritation, confusion and fascination with Rikako an aspect of growing up that is as close as dammit as universal.

Ocean Waves (I have to say I prefer the literal English translation of the Japanese title, 'I Can Hear the Sea') is very much a Ghibli work in its uncluttered and evocative artwork and animation (real Kōchi and Tōkyō locations are nicely captured here), Nagata Shigeru's Joe Hisaishi-esque music score, and the gentle and thoughtful manner with which the story unfolds. It also ably demonstrates – take note western studio chiefs – that stories don't have to be complex, overwrought, or play to convention to provide a rich and emotionally truthful viewing experience.

The anamorphic 16:9 transfer here is in many ways typical of others you'll find in Optimum's Studio Ghibli Collection, being clean, with a well balanced contrast range, subtle pastel colouring and solid black levels. The fine detail fuzziness betrays the NTSC to PAL transfer, at least on larger screens, though the slightly stuttered animation style that will be familiar to manga fans does help to disguise any fast movement issues this may have produced. There are traces of minor edge enhancement and compression artefacts can been seen on areas of similar colour, but thankfully neither are intrusive. The image is also windowboxed on all sides, which will be less obvious on older CRT TVs than it is on modern flat screens.

A clean, clearly recorded and very nicely mixed stereo soundtrack that really does capture the atmosphere of the locations, from the deafening buzz of the summer cicadas in Kōchi to that specific montage of sounds you'll hear at any mainline Japanese railway station. The solid dynamic range is best demonstrated by the music, and the stereo separation is subtly inclusive. Nothing flashy here, but an appropriately low key and pleasing job.

There is, I'm pleased to say, no English dub included here. The English subtitles are removable, but not via the main menu.

Only a Trailer (1:33), a dialogue free piece that sells the film on its teen romance angle.

A lesser seen film from one of the world's premiere animation studios that may not have the eye-opening dazzle of the studio's fantasy work, but has still really connected with the audience that has so far discovered it, many of whom regard it as one of their favourite Ghibli films. Optimum's DVD is a disappointingly bare bones affair, particularly for a full priced disc of a film of just 72 minutes in length, but the transfer is pretty good and the soundtrack well mixed, and if you can find it at a discount it's still well worth hunting out.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for all Japanese names.

|