|

Some while ago now, I remember having a conversation with fellow reviewer Camus about the importance of contextualising movies to the year and country in which they were made, one that made me even more aware of how difficult the process of doing so is for a good many people. It's not just that we're looking at images, filmmaking styles and performances that are sometimes radically different to the ones we use to define the present norm, but that they often feel to many like primitive incarnations of them, the current style in its early stages of development, so to speak. This is further heightened by the condition of the prints of some of the older films, their sometimes more primitive practical effects, and even the fact that they were shot in black-and-white rather than colour. It's understandable to a degree, as I discovered when I screened D.A. Pennebaker's genre-defining Dont Look Back (and no, there is no apostrophe in that title) to a class of young media students some years ago. This is a generation that has grown up with the hand-held camerawork of the modern documentary and the dramatic works that have adopted a faux-documentary style. It thus proved hard for them to appreciate the ground-breaking nature of Pennebaker's film, when to their media-weary eyes it the sort of thing they saw on TV almost every day, only dingier, fuzzier, and featuring a singer whom they were only vaguely aware of through their dad's record collection. One of the class in question was particularly scornful, not just of the filmmaking, but of Bob Dylan's use of the word 'cats' as a hip term for people. I felt compelled to point out that the slang used by her and her contemporaries will likely seem every bit as comical to the generation that follows, when they redefine what constitutes the language of cool. And yes, I am aware that even this term has since been superseded by any number of short-lived replacements.

Surprisingly, perhaps, I've never really had any problem contextualising movies. Indeed, I became hooked on silent cinema at an early age precisely because of its unique look and feel, and had just enough knowledge of film history by then to be aware of at least a spattering of contemporary works against which to judge any such film by. But one of the of the joys of cinema is that there's just so damned much of it, and even if you watch everything you could clap your eyes on for decades on end, you'll still have seen only a fraction of what's out there. Retrospective film investigation is thus littered with surprises, joyous jolts to your expectations for a place, a period in film history, or even a specific filmmaker. It's the sort of unique thrill that film devotees today will experience in abundance when first encountering the works of F.W. Murnau, G.W. Pabst, or early Fritz Lang for the first time, and if you're unfamiliar with the early films of one Carl Theodor Dreyer, then get ready for a similar expectation-busting drop of the jaw.

I first saw Dreyer's extraordinary 1932 horror film Vampyr (full title: Vampyr: The Strange Adventure of Allan Gray) so many years ago that I cannot pinpoint the year, only the decade, and remembered so little about it that when Eureka released it on DVD back in 2008, I felt almost like I was coming to the film for the first time. Almost. Although much of it had faded from my overcrowded memory, one sequence had burned itself so indelibly into my brain that I was able to recall it almost shot for shot. As a young film student, I was startled by its use of a technique I just did not associate with films of this vintage. Later, as a film devotee of many years standing, I remain startled by the sequence, as while it has been reworked by other films since, I've never seen it handled anywhere near as effectively as it is here. I'll get to the scene in question later, but I'm willing to bet that those who know the film will have already made an educated guess at the one I'm referring to. That said, there is plenty of room for speculation, as Vampyr doesn't just have one ground-breaking scene, it's littered with them.

On paper, at least, the plot of Vampyr has a generically familiar ring, but it’s important to remember that we're talking 1932 here (the film was actually shot in 1930), the only previous vampire movie of note was F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu, which by then was effectively a lost film. Indeed, Dreyer's film was completed before Universal's genre-defining Dracula hit cinemas the world over, but its release, to the director's understandable anger, was held back by its distributor until the Hollywood horror double of Dracula and Frankenstein had done its rounds. It's also worth noting that the inspiration for Dreyer's film was not Bram Stoker but Sheridan Le Fanu, whose genre writings predated Stoker's by several years and were a direct influence on Dracula.

Vampyr begins when the sub-titular Allan Gray (Julian West) arrives at a secluded riverside inn located in the hamlet of Courtempierre. Unlike his contemporaries in Nosferatu and Dracula, Gray has not come here on business, nor is he driven by ambition or duty. He is, the opening caption informs us, "lost in the border between reality and the supernatural," the result of his fascination with demonology and vampire lore. Evidence of supernatural activity is all around him, while the danger it represents is first suggested when he receives an unexpected and unsettling visit from the ageing Lord of the Manor (Maurice Schutz), who issues an ominous warning and leaves a package that is only to be opened on the event of his death. It's a demise not long in coming and witnessed by the curious Gray, whose fate then becomes entwined with a threat facing the Lord's two daughters, Gisèle (Rena Mandel) and Léone (Sybille Schmitz), from an ageing female vampire and the collusive local doctor.

Thera are a few recognisable touchstones for the genre-familiar here, and there are more to come, notably in the killing of a vampire in its grave by driving a stake that through its heart, and the nature of the package left for Gray in his room, a book on vampires that outlines their nature and how to defeat them. It's a plot device also employed in Nosferatu, one whose visual presentation here clearly identifies this film as one made during the transitional period from silent to sound cinema (the film was shot silent and its soundtrack post-dubbed in three languages). But, as is pointed out on the second commentary track on this disc, the magic of Vampyr is not in the tale itself but in the extraordinary manner of its telling.

As a contemporary of Tod Browning's Dracula alone, Vampyr makes for fascinating comparative viewing. Whereas Dracula was adapted from a successful stage production of the novel and retained a little too much of its staid theatricality, a key influence on Vampyr appears to be the early surrealist films, not for specifics of their content but their dreamlike atmosphere and sometimes fragmented approach to narrative. This inspirational difference is reflected in the differing visual styles of the two films. Both employed the talents of master cinematographers who would go on to become directors themselves, but where Karl Freund's camera remained immobile for much of Browning's film (when it did move, however, the results were memorable), in Vampyr, Rudolph Maté's is almost constantly in motion, always with purpose, and with a sometimes disarmingly modern feel to its aesthetic.

Considerably more daring and visually adventurous than Dracula, Vampyr also – if you are able to view the film in the context of its time and place – leaves most vampire movies that followed looking a little anaemic by comparison. Take Gray's early investigation of a run-down and seemingly deserted factory building. The journey there is disconcertingly peppered with ownerless shadows, including one of a gravedigger whose actions are reversed (seriously, in the context of this fruitful sub-genre, a sizeable paragraph of subtextual analysis could be written on this image alone). On reaching his destination, Gray encounters the disembodied shadow of a one-legged soldier whose journey through the building eventually reconnects it to its lost-in-thought owner, allowing the two to reconnect and depart in unison. Shadows figure prominently throughout the film as representations of the spiritual aspect of the vampire, a dark trace of the human that once was, but still capable of taking a life. However, as Tony Rayns rightly suggests, the scene in which the Lord of the Manor is murdered by one of these shadowy figures may well be intended to be read symbolically rather than literally. If you like your narrative readings straightforward then be warned, as almost every scene is open to multiple and often complex interpretation.

The film reaches a peak of imaginative boldness in its most justly celebrated sequence, the one that haunted me for so many years. It kicks off when a daydreaming Gray breaks into two semi-transparent entities, one of which discovers his own corpse laying wide-eyed in a coffin that is being prepared for burial. Except he's not dead. How do we know this? Because Dreyer shoots the bulk of the scene from the viewpoint of Gray's immobilised body, as the windowed lid of the coffin is lowered and screwed into place while the ageing vampire looks down at him, then continuing in a similar vein as the coffin is carried through the house and outside towards its place of burial. Not only is this sequence astonishing for its time, it remains uniquely disturbing to this day, brilliantly encapsulating a very specific terror that few of us would probably be aware we were susceptible to until we see it presented in this manner. It works so well in part because it touches on a very tangible fear that a good many of us will have inadvertently been exposed to. The upward views of passing doorways and downward-glancing characters as the camera-in-the-coffin is carried past them will certainly be familiar to anyone who has been wheeled through hospital corridors to an operating theatre, an experience strongly linked to helplessness and an enforced drift from consciousness. And I know of few who have been through it who've not felt just a flicker of fear that they might never wake from this deepest of sleeps.

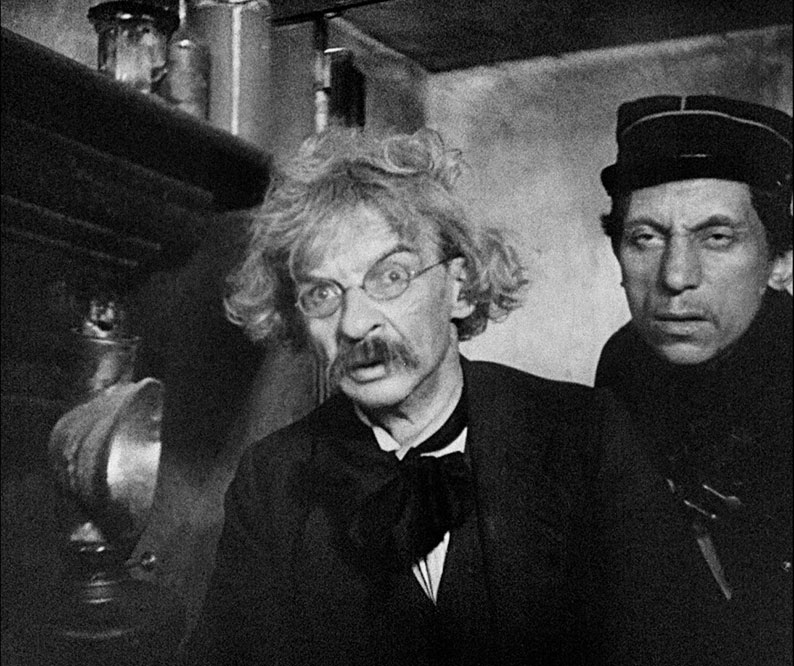

With the majority of action presented as it is experienced by from Gray, you'd expect the central performance to an audience-engaging one, but the role of Allan Gray is taken not by an experienced actor but by Julian West, aka Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg, the aristocrat who funded the film in exchange for being cast in the lead role. Much has been made of his near-expressionless portrayal, but for me it is perfectly in keeping with the film's surrealist overtones – more than once West reminded me of the suited protagonists from Un Chien Andalou, and his wide-eyed confusion seems just right for a man lost between reality and the world of the supernatural. When a strong performance is needed, though, the film gets it in the shape of Sybille Schmitz as Léone, who in one of the film's most skin-crawlingly creepy sequences, facially transforms herself from an injured innocent to a demonic monster without for a second overplaying the role (that she is sitting upright in a chair as she does so can't help but prefigure the scene between Regan and the psychiatrist in The Exorcist). It's a shot that also typifies Dreyer's consistently superb use of close-ups to connect us with character or to draw our attention to (and occasionally misdirect us with) detail.

Although painstakingly restored for this Blu-ray release (more on this below), the still imperfect nature of the source material and the resulting image may prove off-putting for some. For my money, however, this is a contributory factor to the film's still-potent ability to get under your skin in genuinely unsettling manner, adding to its nightmare quality and visually aligning it with the early surrealist cinema from which it draws influence. I seriously can't imagine any of this working even a fraction as well in pin-sharp, CG-assisted colour, which apart from anything else would seriously dilute Dreyer's use of the binary oppositional forces of deathly shadow and liberating whiteness, a religious metaphor put to particularly powerful use in the film's finale.

Seriously undervalued on its release, the true greatness of Vampyr has only been fully appreciated with the passing of time. That it stands out so starkly from its contemporaries is one thing, but 90 years after its initial release, there's still been nothing quite like it, not just in the vampire subgenre but in cinema in general. It’s a subtextually complex work of surrealism-tinged horror whose technique alone is cause for fascination – there are camera movements and effects here that dazzle in their complexity and execution – and I can think of few other films of this vintage that can still give me the serious shivers on every viewing. Tod Browning's Dracula may well be the film that launched the vampire genre and defined its codes and conventions for decades to come, but it's Dreyer's bolder, infinitely more imaginative and adventurous film that has best stood the test of time, and as such is more deserving of classic status.

The transfer that adorned the previous Eureka Masters of Cinema DVD release may fall some way short what we have since come to expect from a digital restoration of a film of even this vintage, but it’s worth remembering that it was carried out in 1998, when the digital restoration was still in its infancy. In addition, all of the original film elements had been lost and the surviving prints were riddled with wear and damage. As a result, that earlier transfer displayed sometimes flickering variations in contrast and brightness and ever-present dust spots, as well as scratches, brief but still visible damage, and frequent picture instability within frame. Clouding the issue a little is that some of the fuzzier-looking shots were designed to look that way, the result of an experimental technique achieved by shooting through backlit gauze in order to give these shots an indistinct, fog-like appearance, something the film's age and condition could make seem like the result of extreme wear.

The 1.18:1 transfer on this Blu-ray release was sourced from a new 2K restoration by the Danish Film Institute, supported by the MEDIA program Creative Europe. It’s one that took over a decade to complete and drew on material from several European archives to create the most high-quality, faithful presentation possible of the film possible for its 90th anniversary. The improvements over the previous restoration are substantial. That detail definition has been improved is to be expected, but what really impresses is just how much of the former damage and dust has been eradicated, with even some scratches (including ones across faces, one of the hardest things to remove without compromising the image) successfully cleaned up. Indeed, we are informed by the booklet that 239,296 items and 616 scratches needed to be manually fixed, and due to the global pandemic, these fixes were performed by a single person, Claus Greffel, the Digital Restoration and Mastering Technician at DFI. Sir, I salute you. The brightness and contrast flickering has been substantially reduced, as has the previous instability of the image within the frame. Due to material in varying conditions having been drawn from a variety of sources, the contrast and black levels are still far more aggressive in some shots than others, but shadow detail in many has definitely been improved. Given what the restoration team (and particularly Mr. Greffel) had to work with, it’s a truly remarkable job.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono audio soundtrack has also been restored, and you don’t need to own the previous DVD release to appreciate the improvement made here, as you’re given the option to play the film with the newly restored soundtrack or the unrestored original, and can switch between them on the fly for comparison purposes. Being one of the very first films from the sound era, the dynamic range is going to be severely restricted even on the restored track, but the music and effects have a little more body here, and the almost constant background hiss of the original has been all but eliminated.

Optional English subtitles kick on by default but can be switched off if you prefer.

Several of the special features on this new Blu-ray have been carried over from Eureka’s 2008 DVD, but given their collective excellence this is a most welcome move, and they have been joined here by three new interviews of similarly high quality.

Tony Rayns Commentary

Resident filmmaker, film festival programmer, and Asian cinema expert, Tony Rayns, provides a typically detailed, educational, and consistently interesting look at the film's background and production. This includes information on Dreyer, the locations, the performers, the filming, the construction of specific scenes, and the cuts made by the German censor. He also deconstructs some of the sequences and imagery, something you'll almost definitely find yourself also doing, and he’s happy to remain a little mystified by a couple of aspects, which are then explained by...

Guillermo del Toro commentary

A major coup for the Masters of Cinema series back in 2008, given that this track does not feature on the US Criterion DVD or Blu-ray release, it has thankfully been carried over to this Blu-ray release. One of the leading fantasy filmmakers working today, a man whose first feature was the genre-advancing vampire movie, Cronos, del Toro has both a passion for and an extensive knowledge of the genre and has a particular love for Vampyr, which he believes is Dreyer's masterpiece. As with all of the best del Toro commentaries, this is both bristling with detail and enormously entertaining – up front he describes his contribution as "the equivalent of inviting a fat Mexican to your house, feed him, and then you have to listen to him for mercifully a short time and then disagree, agree, insult or share any of my opinions." Del Toro sees the film as a cinematic memento mori, and don't worry, he provides a full history of that particular artistic subgenre, along with a detailed examination of the film's style and complex substructure, particularly – as a Catholic – its religious reading. There are some lovely moments in here, notably his assertion that Jean Cocteau was a magician but Dreyer was a prophet, and his gorgeous description of the surrealists as "beautiful savages of the id." Wouldn't you love to have said that? I was also amused (although perhaps also a little deflated, as I thought I'd scored a minor coup on this one) to discover that I was not the only one who'd spotted the similarities between this film’s village doctor and Professor Abronsius in Roman Polanski's The Fearless Vampire Killers, as well as the death of a bad guy in Peter Weir's Witness to the manner in which the doctor finally meets his end. The great thing about both of these commentaries is not only are they completely pause-free, but there is almost no duplication of information, a rare an much appreciated thing for multiple commentary discs.

Visual Essay by Casper Tybjerg (36:01)

Not content with going one up on Criterion with the del Toro commentary, Masters of Cinema also licensed from them this documentary exploring what influenced Dreyer to make Vampyr, commissioned specifically for the 2008 Criterion DVD release. A scholarly affair, but in a good way, it provides yet more information on the production, as well as visual evidence of some of the points raised by the commentaries. It also includes a number of archive photographs and some interview footage from the Jøgen Roos documentary detailed below.

Carl Th. Dreyer by Jøgen Roos (29:59)

A Danish-made interview with Dreyer conducted towards the end of his career after the French premiere of his final film, Getrud, in which he discusses specific aspects of each of his films in turn, which are illustrated with extracts of a useful length. The sequences in which he talks about Vampyr are incorporated in their entirety in the Casper Tybjerg documentary above. Included here is footage of the Gertrud premiere, which includes brief interviews with admirers François Truffaut and Henri-Georges Clouzot, and we get to see Dreyer encourage an apprehensive Jean-Luc Godard to attend a directors' dinner.

Kim Newman on Vampyr (22:24)

New to this release is an interview with walking (or in this case, sitting) horror encyclopaedia, Kim Newman, who kicks off with an overview of the evolution of the horror film and how the vampire subgenre was established by Universal’s adaptation of Dracula. He talks about the loose connections to Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, the film’s largely non-professional cast, its atmospheric use of real locations, its pacing, its celebrated premature burial sequence, and what he rather wonderfully describes as the “horror of whiteness” captured by its imagery. He pertinently suggests that you have to be in tune with the film for it to really work, draws parallels with the later The Lost Boys and Near Dark, and draws on an old favourite by describing it as “a horror film for the ages.” A most welcome addition.

David Huckvale on composer Wolfgang Zeller (36:39)

Oh, how I’ve missed David Huckvale’s meticulous breakdowns of scores and the lives and careers of their composers. Here he does likewise with Wolfgang Zeller, outlining his earlier work (including one unfortunate blot on his CV that I’ll let you discover) before examining the score that he has become best known for, deconstructing its compositional elements and purpose in fascinating detail. As ever, the sections that he examines and plays on the piano are then shown fully orchestrated in clips from the film itself. This is the second of the new features unique to this Blu-ray edition.

David Huckvale on Sheridan Le Fanu (11:38)

For the third and last of the new special features, Huckvale is back with a rare non-musically themed look at the life and work of Carmilla author Sheridan Le Fanu. He highlights the elements that Dreyer drew from In a Glass Darkly, the 1872 collection of short stories by Le Fanu in which Carmilla was first published, as well as the influence of ideas 18th Century Swedish Christian mystic Emmanuel Swedenborg, from one of whose books he also reads extracts. Once again, a compelling extra.

The Baron by Craig Keller (14:25)

A specially made 14 minute documentary, written and narrated by Craig Keller, that delves into the life of Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg, one illustrated with a sizeable collection or archive photographs, artwork and documents. Given how little I knew about this individual, this proved highly educational.

Censored Scenes from the French version (3:50)

The restored print on this Blu-ray is of the version released in Germany, which received cuts to two scenes by the German censors. The excised shots survive in the French language version but with soundtrack problems, making it difficult for the restoration team to re-insert them into this print. They have thus been included as an extra feature, something of a relief given statements made about their importance by both Rayns and del Toro on their commentaries.

Book

A handsomely laid out 100-page book that begins with textual extracts from the original Danish film programme (the entire plot is included in the summary, so I’d absolutely avoid reading this before a first viewing of the film), using scans of some of the page spreads as illustrations. Next is a lengthy and impressively detailed essay titled Film Production – Carl Dreyer by Jean and Dale Drum, extracted from their book My Only Great Passion: The Life and Films of Carl Th. Dreyer, which was published in 2000 by Scarecrow Press. After this is an in-depth essay on the film by Tom Milne, extracted from The Cinema of Carl Dreyer, which is followed by a fascinating interview with Baron Nicholas de Gunzburg by Herman G. Weinberg and Gretchen Weinberg and published in the Spring 1964 edition of Film Comment. He talks openly and revealingly about the making of the film, and early on states that he was and admirer of Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (as are we all) and that the only other horror film he liked was Nosferatu. A transcript of a lecture given by Dreyer at the Edinburgh Film Festival in August 1955 reveals a great deal about his thoughts on stylisation, photography, and the use of colour. Some welcome notes on the 2000 restoration by Martin Koerber – which appeared in the booklet that accompanied the previous DVD release – are handily supplemented by a brief 2022 update, also by Koerber, about this new 2K Danish Film Institute restoration. Rounding things off is a sizeable collection of production stills, something that usually appears as an on-disc extra but that adds to this book’s premium feel.

As someone who has always championed F.W. Munau’s Nosferatu as the king of vampire movies, I’ll freely admit that Vampyr is the film that comes closest to stealing that famed earlier work’s crown. 14 years after first revisiting the film, it remains for me the most imaginative, exciting and poetic work the vampire subgenre has yet produced, and one of the most hauntingly beautiful examples of cinematic horror that I’ve yet seen. The earlier DVD was a must-buy, but the improvements made by this new 2022 restoration make this new edition an essential purchase whether you have that or not, particularly as it includes all of the special features from the earlier DVD, plus three new ones, and an accompanying book that expands on the original’s content. A phenomenal release that gets our highest recommendation.

|