|

It

is impossible to overstate the importance of Bram Stoker's

seminal novel Dracula when discussing the vampire

genre. Its influence on the form and development of vampire

movies was so great that we were into the 70s before English language films of the

genre began to seriously shake off The Count and head

in new directions.

When

tracing this sub-genre of the horror film back to its

origins, a key starting point is often Tod Browning's

1931 Dracula, which starred Bela Lugosi as the eponymous Count. There

is a logic to this. Ask anyone to profile a typical vampire

(and I've done this many times with media students

and always get the same result) and they will give you

Lugosi's Dracula every time – the dinner suit, the cape,

the slicked-back hair, the East European accent,

the old gothic castle, the bats, the coffin in the basement.

Browning and Lugosi effectively shaped the movie vampire

for decades to come, and even when films began to move in

new directions, it was Lugosi's creation that remained

the archetype and the basis for pretty much all genre

parody to this day.

Dracula may have been the first vampire novel to be turned into

a feature film, but if Browning's movie was the first

officially sanctioned adaptation, then it was

not the first film version per se. That honour, possibly, belongs to a 1920

Russian (or, some say, Hungarian) film that either never

actually existed or has disappeared from the face of the

earth, a fate that almost befell what many regard as the

greatest vampire film of them all, F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu.

Nosferatu towers over the vampire genre but was so nearly lost

to history. 'Freely adapted' from Stoker's novel, official

permission was never obtained and Stoker's widow took the studio

to court over copyright infringement and won. With the

studio in bankruptcy, no monetary recompense could be

secured, so the highly unusual (and for cinema itself,

potentially catastrophic) decision was made to order

all copies of the film destroyed. Fortunately for us all, a couple

survived (exact details are hazy here and no two stories

appear to agree completely), one of which eventually made

its way to America and to Universal studios, where it

was to influence key aspects of Browning's film.

For

the first fifty years, the development of the vampire genre

was gradual, following rules that were defined by its earliest

works but modifying them on a film-by-film basis. Writing

in Narrative and Genre, Nick Lacey neatly summed

up the concept of genre development with the simple phrase "the

same but different" – when an audience watches a

movie they arrive with certain expectations, an understanding

of the rules of the genre in which it sits but coupled with the hope that it will nonetheless deliver something

new. Genre evolves through an unspoken collaboration

between the audience and the film-makers, and those producing

films certainly understand this, knowing they have to

give the audience what they want, but not always what they expect.

In

retrospect, Nosferatu cannot really be regarded as being part of

this process and stands as a one-off – a single vampire movie does not

a genre make, and when it really kicked off with Browning's Dracula, Nosferatu was effectively a lost film.

But Nosferatu was also a European film,

and although many of Hollywood's early directors either

hailed from Europe or were influenced by its cinema, the

films themselves did not reach a fraction of the world

audience of their Hollywood bretheren, a situation that has changed little in the subsequent decades. It is only

through the distancing effect of time that Nosferatu's

essential role in genre development can be properly assessed, as

well as its influence on key later works. In standing

alone, uninfluenced by preceding genre films (simply because

there were none), it remains the most singular work in

the first fifty years of the genre's history, in its

style, its visual inventiveness and its subtextual complexity.

And in the bold nature of its adaptation of the classic text, it now seems

years ahead of its time.

Nosferatu's

free adaptation of Stoker's novel changed not only the

names of all of the key protagonists but also many of their

roles in the narrative. In the novel, young solicitor

Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania to close a deal

with Count Dracula on a property located close to his own in Whitby.

This element remains in Murnau's film, but here Whitby

becomes Wisborg and Harker is Thomas Hutter, the almost

child-like husband of mournful Ellen, sent off to secure

the deal with Dracula substitute Count Orlock by his greedy,

almost possessed boss, Broker Knock. Knock is secretly

in league with Orlock, and his increasing madness eventually

places him in an asylum, where he fulfils the role of

Dracula's insect-eating servant Renfield from Stoker's original.

Hutter's

journey to Castle Orlock, via an inn at a nearby village

populated by frightened and superstitious locals, is very

much how things would play from this point on. He is effectively

blinded by cheerful optimism at the personal advancement

this deal might bring him, prompting him to brush off

the warnings of these simple peasant folk and mockingly hurl to the floor a book he finds in his room that warns of vampires and other creatures

of the night. The next day, he is delivered to an arranged meeting

place by an agitated coachman, who is keen to flee before the

sun goes down, and is met by a second coach and a sinister-looking

driver, who conducts him at impossible speed to Orlock's remote

castle.

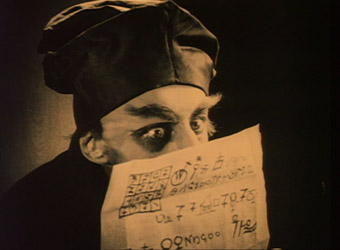

This

is our first encounter with the film's greatest and most

memorable creation: Orlock himself. As played by Max Schreck,

the inspiration for Orlock can certainly be found in the

novel, but as a screen creation he bears little resemblance

to the suave ladykiller of Lugosi et al. With his bald

head, pointed ears, extended fingernails and long, centrally

located fangs, Orlock is like a rat in human form, a truly

supernatural creature whose very image is enough to disturb

anyone with an ounce of sense, something Hutter seems

to have left back in Wisborg. As they discuss the deal over dinner,

Hutter accidentally cuts his finger and Orlock's reaction

is instantaneous and disturbing – he grabs Hutter's finger

and sucks the blood from it, causing Hutter to retreat

in alarm. Orlock slowly advances on him and the screen fades

to black, and we are left to speculate on the nature of

the assault that follows. Was this a vampiric attack

or a monstrous seduction? The next morning

Hutter is left with no memory of the incident and dismisses

the two holes in his neck as insect bites.

This

is a key scene altered from the novel that was to be recreated

in Browning's 1931 version. In the novel Harker cuts himself

shaving, but Browning also chose to stage the scene during

contractual discussions over dinner, clear evidence that

at least some of those involved in the production had

seen Murnau's original. But then Browning was to play

his own specific games with Dracula's characters

and structure, as was Terence Fisher in Hammer's spitited

1958 reworking.

It

is with Orlock's second attack on Hutter that the film

really comes into its own and when Murnau starts to show

just how ahead of the game he was, in horror imagery,

generic subtext, and in his striking use of film as a storytelling medium.

Hutter, unable to sleep, opens his bedroom door to reveal

the distant figure of Orlock, standing bolt upright, eyes

staring straight ahead, like a creature that has been

shocked to death. As Orlock slowly advances, Hutter reacts

by cowering in his bed, pulling the bedclothes up like

a frightened child, until swathed by Orlock's demonic

shadow. At the same time, back in Hutter's home town of Wisborg,

Ellen wakes with a start and begins sleepwalking. Restrained

by her friends, she suddenly calls out to her husband,

and Murnau cross-cuts between the two locations, establishing

a very real connection between the attack on Thomas and

Ellen's anguish. In a genuinely astonishing edit, Ellen,

in her bedroom, reaches out to frame left for Thomas

and we cut to Orlock, having just finished with Thomas,

turning to look frame right, and he seems to be looking

directly at Ellen, despite the hundreds of miles

between them. This almost telepathic connection is echoed later when Ellen

says "He is near" – it is never certain whether

she is referring to the returning Thomas or the approaching

Orlock.

Most

adaptations of the Dracula story have split themselves

evenly between the Harker's encounter with the Count in

Transylvania and the cat-and-mouse games fought on English soil between Dracula

and his enemies, who are led by knowledgeable Professor Van Helsing. Nosferatu is probably

unique in that it devotes so little screen time to this

second half of the story, and we are 69 minutes into a 90

minute film before Orlock even sets foot in Wisborg. When he

does so he brings more than the threat of vampirism –

he brings disease in the form of the plague, a real world contangion that was spread by the very creature that he most resembles.

Orlock comes to Wisborg solely to possess Ellen

(quite why he becomes so obsessed with her on seeing her

picture is not clear), but he is more than a vampire looking

for fresh victims – he arrives as an angel of death, his

very presence laying waste to everything he encounters.

In generic terms, Murnau was once again ahead of his time.

55 years before Kathryn Bigelow presented vampirism as

an AIDS-like infection that could be passed on through

body fluids in Near Dark, Murnau had

painted a most vivid and convincing picture of the vampire

as a spreader of lethal disease.

Orlock

remains the most extraordinary film incarnation of Dracula

and in some ways its most iconic, despite Lugosi's genre-shaping performance. With dialogue sparsely represented by

title cards, the emotions, fears and intentions of the characters are all externalised

through Albin Grau's costumes and sets, Güther Krampf

and Fritz Arno Wagner's cinematography, Murnau's direction,

and Schreck's central performance, resulting in an expressionistic

masterpiece whose imagery has become a part of film lore:

Orlock walking the deck of the death ship, rising bolt upright

from his coffin, or emerging

slowly from the hold on its arrival in Wisborg; his hunched

shadow as he climbs the stairs towards Ellen's bedroom;

the still startling symbolic shadow that reaches

out and grasps Ellen's heart; Orlock ghoulishly feeding off Ellen as dawn

approaches. All are all moments that once seen are

never forgotten, their impact as imagery given extra meat

by their potent thematic and symbolic subtext.

As

something of an outsider in generic terms, Nosferatu nonetheless contains some of the genre's most recognisable iconography: Orlock sucks the blood of his victims by biting

their necks; it is suggested that he can shape-shift into

a wolf (though this is never seen); he lives in an old

castle and sleeps in a coffin; he has supernatural powers

and can open doors telekenetically and even pass through

closed ones; terrified locals try to warn unwary travelers,

who fail to take heed. The notion that

vampires can be destroyed by sunlight also originated here (in the novel, a

less powerful Count Dracula walked freely around the streets

of London in the daytime), which has since become one of the

genre's few unbreakable rules. Another key genre element, however,

is completely ignored, with religion offering no comfort

or protection – indeed, it is barely mentioned here, the cross that was to protect vampire hunters and potential

victims from Browning's film onwards appearing here merely as a headstone

(in one of the film's most striking images, as Ellen waits

in a seaside graveyard for Thomas's return), or almost coincidentally as a chalk

mark on the door of a plague house.

Key

characters from the novel and later films play different

roles in Marnau's story. Van Helsing stand-in Professor

Bulwer is, in narrative terms, completely ineffectual,

his function here being purely to ground the vampire in

some sort of reality by comparing him to stranger scientific

curiosities like the Venus Fly Trap – at no point is

he even proposed as a potential adversary for the Count.

Ellen, on the other hand, is a far stronger character

than most of her successors, with

the generic tradition of women as victims who scream,

faint, become possessed and ultimately collaborate with

their attacker having no place here. Though clearly affected

by Orlock's controlling power, Ellen fights it with every

ounce of her strength, and invites the Count to her bedroom

not as a manipulated victim or a bride with an unfulfilled

longing, but with the intention of keeping

him at her bedside until the break of dawn in order to destroy him.

She does so, as suggested by the narrative, as a 'pure'

maiden, suggesting an unconsummated marriage, a proposal reflected in her sad demeanour and her otherwise inexplicable reaction

to the cut flowers presented to her early in the film

by her husband – in a childless, barren marriage, the sight

of life being cut down, whatever the form, is painful

for her. Orlock is the opposite of Thomas in this respect,

a potent, aggressive force who can deliver what Thomas

cannot, but at a terrible price.

Time

has moved on and the nature of the cinematic form has

drastically changed in the century since it's birth. It

is unlikely that modern viewers would be as frightened by Nosferatu in the way its original audience

must have been. But much of it does remain genuinely chilling

– Murnau and Schreck have created a film in which nightmare

imagery replaces the everyday, pictures raided from our

dreams and presented on screen for all to see.

If

it remained widely unseen for decades, Nosferatu was eventually to make its mark on modern cinema and television. In 1979,

it was remade by maverick German director Werner Herzog

with Klaus Kinski in the lead, a very different film to

Murnau's original that has always divided opinion but is fascinating in its own right. Schreck's

Orlock became the basis for the vampire Kurt Barlow in

Tobe Hooper's mini-series adaptation of Stephen King's Salem's Lot (in the novel, Barlow is

a more classical vampire), and in the first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the demon known

as The Master is clearly modeled on Orlock. In Batman

Returns, Christopher Walken's character is named

Max Schreck in tribute to this film's lead actor, and the recent Shadow of a Vampire fashioned

its narrative around the making of Nosferatu,

suggesting that Schreck was not an actor but a genuine

creature of the night. Not so long ago the BBC screened a commercial

for one of its own services that was fashioned around a key sequence from the

film, and Orlock has even turned up intermittently in

the sketch series The Fast Show to threaten

a maiden in her bed and then deliver a comic line that

ends with the word "Monster!"

Nosferatu was the first major vampire movie and remains in many

ways the genre's most extraordinary achievement. In its

visuals, its expressionist sets and acting, its narrative

and thematic depth, its sometimes groundbreaking editing,

it was years ahead of its time, and its importance in

genre history has only in recent years been fully appreciated.

Remember too that every film that followed had previous

genre works to draw on or react to – Nosferatu was a true original, and every frame in the film is the

result of the startling vision of Murnau and his collaborators.

For my money, despite some stiff competition, Nosferatu is quite simply the vampire movie.

Let's get one thing straight. If you're expecting a restoration

of the quality of Eureka's recent two-disc version of Fritz

Lang's M then forget it.* Almost every copy

of Nosferatu was destroyed and every subsequent

print has been struck from one of the very few that survived,

and they were in far from perfect shape. Scratches are plentiful,

as are dust spots and frame damage. On top of that, there

are quite a few frame jumps and the exposure can wander

dramatically in places from one second to the next. But

considering the film's age and history, this is par for

the course and shouldn't harm your appreciation of the work

itself.

We

have two versions to evaluate here, though it could be argued

that there are three, as the Eureka release includes two

discs, one presenting the film in monochrome, the other with a sepia tint. I'm really not sure

of the thinking behind this, unless it's the tinting equivalent

of having a full screen and a widescreen print in the same

box, so you get whichever one you prefer. Of course what

we'd actually prefer is to see the print as it

was projected in cinemas when first shown, and this is what

the transfer on the BFI disc claims to be.

Nosferatu was shot in the days when film stock was just too slow for film-makers to shoot by artificial light, and filming was generally carried on roofless exterior sets. Shadow of the Vampire, in order to accommodate the idea that Schreck himself was a vampire and unable to walk freely in the daytime, suggested that the film was shot by artificial light, but this was not the case. This need to film by daylight should prove restrictive in scenes supposedly set at night, as common sense would suggest that the sky should never be in shot at any time, as this would instantly give the game away. Murnau, however, refused to be restricted by this, and one of the film's most iconic shots has Orlock walking the deck of the death ship, viewed from low down in the hold. The sky dominates this shot and it is clearly daylight, so how on earth is sunlight used to destroy Orlock at the end of the film? If the ship scene had to be shot in the day, how did an audience new to the whole concept of vampire movies know that this daytime shot was actually meant to be night? According to film historians the answer lay in tinting – scenes set at night would have a blue tint, whereas daytime scenes would have a warmer hue. These were indicators that a 1920s audience would have understood, but which have been lacking from every print of Nosferatu shown since those early screenings, and it is this that the BFI disc attempts to rectify. Whether those indicators work as well for a modern audience is debatable, but it's good to have the chance to view the film is it was meant to be shown.

As

to which version is the best, well that's a different story.

The BFI disc has to come recommended as the most authentic,

but in terms of clarity, detail and contrast, the black-and-white

print on the Eureka 2-disc set definitely wins out. The

tinting inevitably takes something away from the picture

in terms of fine detail – the same is true of the tinted

print in the Eureka package. So it comes down to personal

preference: if you want to see the film as it was originally

screened, then go for the BFI disc, but if you want clarity

and detail, then Eureka disc is the one for you.

|

The

BFI disc (above) and the Eureka disc (below) |

|

But

there's another issue here. The picture on the BFI disc

is windowboxed within a black border, which helps with TV

overscan but sometimes crops information on two or more sides,

though this varies wildly and accosionally actually appears

to have more picture information than the Eureka

transfer. The above screen grabs illustrate both this and

the differences in sharpness and detail clarity.

This

seems an odd section to have for a silent film, but both

discs have music scores, and they are different enough in

style to possibly be the deciding factor in which disc is

for you.

The

Eureka disc features an electronic music track that is available

in Dolby stereo 2.0 (this option is only available on the

untinted print on disc 2) or 5.1 surround. Whether this is appropriate

for the film is debatable, as it is music that couldn't

possibly have been heard on its release, and unlike Giorgio

Moroder's electronic score for his recut of Lang's Metropolis,

which as a futuristic story could logically embrace electronic

musical accompaniment, Murnau's gothic vision is rooted

in its time and would seem to demand a more traditional

approach. Having said that, I found much of Gérard

Hourbette and Thierry Zaboitzeff's score here very effective.

If the purpose of a music track is to emphasise and direct the

emotions of the audience then the one here frequently

succeeds, the deep, sinister electronic notes really adding

to the sense of menace in the early stages. As the film

progressed I became less enthralled, as the score veers

towards the avant-garde, losing me completely with the

use of what sounded like typewriter keys being randomly tapped. I have no problem

with the concept of avant-garde music – as a lifelong

fan of Giorgi Ligerti I have watched a music performance

that included screaming and the smashing of crockery and

enjoyed it immensely – but with film scores it has to be appropriate, and here I have to question whether that is the case.

The

BFI disc sports an orchestral score by James Bernard, whose

work for Hammer studios was so much part of their corporate

identity. This is certainly a more traditional musical accompaniment

and on the whole is more effective and more subtle than

the electronic work on on Eureka's disc, but for vampire

movie aficionados there is a down side, and that's one of

familiarity. It's a fine score, no question, but its similarity

to Bernard's score for Hammer's Dracula is impossible to ignore, and as a huge fan of Hammer's version

and Hammer films in general, it at times felt almost as

if the music from the later film had been simply adapted

for this earlier work. Again, it all comes down to personal

preferences, and this is still a very evocative and appropriate

score, though it's a tad disappointing to find it presented

in Dolby 2.0 rather than the room-filling 5.1 it deserves.

Here

again, the two discs differ a great deal. I'll look at the

discs in the order of their release, which puts the Eureka

DVD up front. All of the extras are on disc 1, which contains

the sepia print, a colouration that has also been applied

to almost every extra here.

First

up is an audio commentary on the

film and its background, but by whom is never stated. It

plays in some ways like a lecture on the film and presents

a great deal of information about the narrative, the making

of the film and the various subtextual readings.

Much of this is really interesting, but is delivered not

by an academic, as on the Universal classic horror releases,

but what sounds like an actor attempting to impersonate

Valantine Dyall. This gives the whole thing a slightly artificial

feel, but it is interesting.

There

are two trailers, one for Nosferatu,

featuring extracts from the film and a voice-over from the

Valentine Dyall wannabe and was created to promote this

very disc. It is framed 1.33:1 and runs for 2 minutes 47 seconds.

Inspiring it is not. The other is for E. Elias Merhidge's Shadow of the Vampire, whose release coincided

with that of this disc and is a logical inclusion considering

its plot was based around the shooting of Murnau's film.

This is also famed 1.33:1, is 1 minute 30 seconds long, and the only

extra on the disc not awash with sepia tinting. It sells

the film rather well.

Nosferatu

Recaptured has two subsections. The cheesily

titled NosferaTour runs for just over 13 minutes

and briefly puts a face to Valentine Dyall Jnr. before settling

down into an interesting trip around the locations at which Nosferatu was shot. Freeze frames of the

film are compared with historical and modern photographs

of the actual locations, while Mr. Dyall tells us about

what we are watching, giving some historical background

and information on the present condition or fate of the

buildings, including one location's link to Hammer's first Dracula film. It's an enjoyable extra,

and made me think about taking a holiday to hunt out the

locations for myself (I did this several years ago for the

superb British war film Went

the Day Well?), but you can't help wishing

they'd gone there with a video camera and made a full-blooded

featurette.

A

Visual Legacy runs for just over 4 minutes

and looks at the poster art and the original sketches by

art director Albin Grau and how close they were to Murnau's

final film images, giving a clear indication of Grau's contribution

to the look of the film. Again, this is narrated by Dyall

Jnr.

Origins

of Vampires gives a fairly detailed though

far from exhaustive textual history of vampire lore, using

the rise of Vlad Dracul as its kicking off point, though

no mention is made of the legend's origins in various cultures

before 1431. It's still an interesting read, and even though

written in gothic script as if part of an old parchment,

is still very legible.

Nosferatu's

Controversy is a textual extra very much in

the style of the Origins of Vampires one, giving

a brief summary of the legal action taken to destroy all

prints of the film and one version of how it survived. Nosferatu's

Controversy and Origins of Vampires also appear

on disc 2, but without the sepia tint.

And

so on to the BFI disc...

Christopher

Frayling on Nosferatu has writer Sir Christopher

Frayling, a Nosferatu enthusiast and author

of the preface in the Penguin Classics edition of Stoker's Dracula, waxing lyrical about what is clearly one

of his favourite films. Frayling is a fine communicator

and his enthusiasm is infectious – he covers a lot of ground

well, including the various subtextual readings of the film,

not all of which he agrees with. Divided into subject areas

by title cards and nicely illustrated with clips from the

film and influential artwork, this is a very good extra

and a very detailed look at the key influences on the film's

look and structure, as well as some of the possible readings.

The featurette is presented 1.33:1 and runs for just over 24

minutes.

F

W Murnau is a reasonably thorough text-based

biography of the great German director, written by critic

and writer Philip Kemp. A full filmography is included at

the end.

James

Bernard and the Music is also text-based and

is a three-page contribution by the composer of the score

for the BFI disc on his approach to the project, plus a

brief biography and full filmography of Bernard himself.

Enno

Patalas on restoring Nosferatu is a detailed

essay on the restoration of the film, which is stored on

the DVD in PDF format and needs a computer with a DVD-ROM

drive to access. You will need Adobe Acrobat Reader to access

it, unless you have a Mac with OSX, which opens PDF files

without extra software. It's worth getting access to this

extra if you are interested in the restoration process,

as it does make for very interesting reading.

The Web Link is a bit of a cheat, as clicking

on it, even if you are running the disc on a DVD-ROM drive,

just supplies you with a message telling you to place

the disc in your computer and locate and open the file Nosferatu.html.

Do this, though, and you will be supplied with a link that

takes you to the BFI's web site, and this approach does

at least make the link accessible to all computers and operating

systems, not just PCs.

For a young audience raised on Buffy and Blade and with little knowledge of genre history, German Expressionism, or even silent cinema, Nosferatu might to prove initially inaccessible. But trust me, if you really care about the vampire genre as a whole, this will pass. For genre fans who know their film history and their vampire lore, this is the godfather of vampire movies, a gorgeous gothic creation and one of film history's most darkly beautiful works. It remains so in part through a bizarre twist of fate, for had Stoker's widow not tried to have all copies destroyed, and had it been the worldwide success that Browning's Dracula became, then who knows, maybe Max Schreck rather than Bela Lugosi would have defined the movie vampire for decades to come, until that figure also became a cliché and fit only for parody. As result, while Lugosi's Dracula is now a figure of fun, Schreck's remains a genuinely creepy and even disturbing creation, a supernatural embodiment of vampirism as a potent and deadly force, and a creature to be genuinely afraid of.

As for which disc to go for, well it's all a matter of personal preference, but recently most I have leaned towards the BFI disc for its more classical score and the restoration of the original tinting, as well as Christopher Frayling's informative featurette. But the Eureka disc sometimes has more picture information, a clearer black-and-white print and a very interesting if somewhat overly 'performed' commentary. Which of course means only one thing if you are a real fan – buy them both.

* Some years after I wriote this review, German film restoration house Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung went to work on the film and delivered the very reconstruction I I here believed we would never see, which was released on DVD by Eureka! under their Masters of Cinema banner. personally I was overjoyed to eat my words.

|