|

Were it not for the Japanese characters, spoken language and titles, it would be disarmingly easy to mistake the opening scene of the 1958 Underworld Beauty for that of a previously unsung American noir from the 1940s. In an industrial region in the dead of night, an unidentified, black-dressed figure walks through down a deserted road, his progress tracked by the shadow he casts on a concrete wall as he passes. He stops at a manhole, which he levers up with a crowbar he has obviously brought with him specifically for this purpose, but as he descends into the sewer below, a lorry approaches carrying two night workers, one of whom is convinced that he saw something move. When the worker lifts the manhole and climbs down the ladder to investigate, however, the first thing his torch locates is the decaying corpse of a cat, which prompts him to recoil and quickly depart. Having hidden himself in the shadows below, the unidentified man waits for the workers to leave and makes his way down the sewer in a wide shot that looks like an outtake from the climax of The Third Man (1949). A short while later, he stops and feels the wall to locate a specific brick, which he loosens and removes, then reaches into the resulting hole to retrieve a handgun and a small pouch containing three large diamonds.

The stateside influence continues as the film switches suddenly from the near silence of the sewer to the boisterous liveliness of a club in which young men and women are energetically dancing to swing music with a physicality that should be familiar to anyone who has watched a movie in which American GI’s dance with local girls during WWII. Nestled within this sea of joyous faces are a spattering of older individuals who are clearly not there to dance and have the appearance of men looking to make serious trouble. All the signs are that something is about to kick off: a cheerful waiter freezes in shocked surprise, drops the tray of glasses he was carrying and scurries away; a man wearing dark sunglasses pauses his card game and looks up; two smoking heavies fix their eyes on something off screen and move in its direction; a barman becomes transfixed and freezes midway through shaking a cocktail; a solitary hood covers a sharp-looking knife with his hat in preparation. Either two rival gangs are about to rumble, or they have all become fixated on a single threat.

The dance number concludes and all eyes turn suddenly towards the man we saw enter the sewer in the opening scene as he walks calmly and silently onto the dance floor and over to the juke box, where he selects a tune that the youngsters resume their energetic dancing to but that is replaced on the soundtrack by the moody strains Yamamoto Naozumi’s noir-infused score. When challenged by the knife-carrying hood, the man lifts the hat covering the blade and plonks it on the hood’s head with a contemptuous grin, and when the hood attempts to block his path, the man roughly pushes him aside. The resulting kerfuffle is overheard by club manager Ōsawa (Takashina Kaku), who grabs a machine gun and turns round in time to see the man standing at his office door, surrounded by the hoods we caught glimpses of earlier. Although surprised to see him, Ōsawa unexpectedly invites the man in and dismisses his men. It’s here that we learn the mystery man’s name is Miyamoto (Mizushima Michitarō) and that he’s here to arrange a meeting with Ōyane (Ashida Shinsuke), the head of the yakuza gang of which Ōsawa is a loyal member. Miyamoto also asks Ōsawa about a man named Mihara (Abe Tōru), and is informed that he is now a regular citizen and running a small oden stall, a career change forced on him by an as-yet unspecified and disabling injury. We then get a taste of why the goons reacted as they did to Miyamoto’s arrival when Ōsawa makes a casually disparaging remark about Mihara and is told to watch his mouth by Miyamoto, a warning that he clearly knows carries some weight.

When Ōsawa nervously responds to Miyamoto’s request and calls Ōyane to tell him that Miyamoto is in the club, Ōyane takes the call in a steam room whilst being massaged by three women dressed only in shorts and brassieres to the strains of a stereotypically Hawaiian tune, instantly establishing Ōyane’s status and giving us a first glimpse of a location that will later play an important narrative role. From the little Ōyane says and his choice of words, we learn that Miyamoto has only recently been released from prison, that Ōyane knows about the three diamonds, and that he would rather like to get his hands on them. “Bring him here,” he tells Ōsawa, “Treat him well. Don’t tell him anything about the stones.” When Miyamoto arrives, he tells Ōyane that he wants to sell the diamonds and give the money to Mihara, who sustained his career-ending injury on the same job that landed Miyamoto in prison. He asks Ōyane to do him a favour and forget about the stones, and Ōyane seems compliant and even agrees to arrange the sale, but the thoughtful look on his face after Miyamoto departs tells a different story.

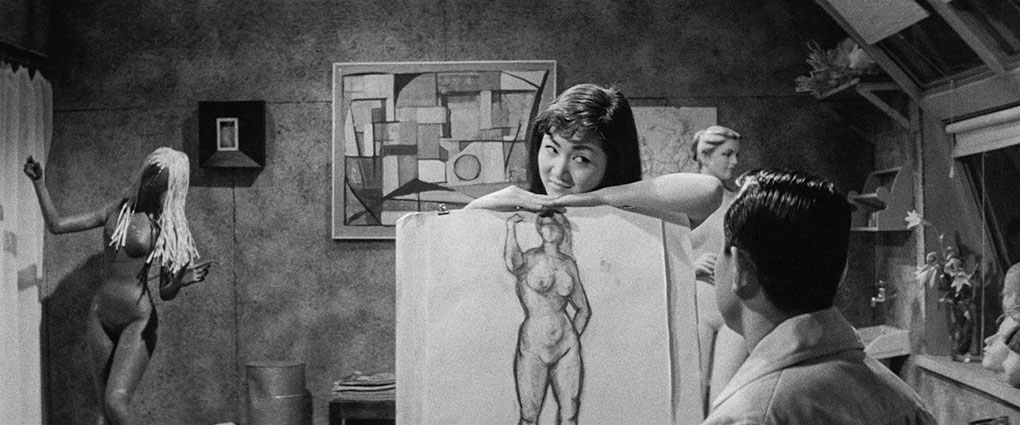

I should note that at this point we’re just 11 minutes into this 87-minute film, and despite still having a slew of questions about the characters, their past relationships and their future intentions, I was already completely hooked, and we still haven’t met the most interesting character. She makes her first appearance in the very next scene when we meet the aforementioned Mihara at his oden stall, where he’s being cheerfully mocked by his sister Akiko (Shiraki Mari) for not seeking revenge against the man who crippled him. He sullenly responds by requesting that she not bring up the past, then angrily snatches an unlit cigarette from her mouth and warns her not to get involved with Arita (Kondō Hiroshi), an artist for whom she poses nude for drawings from which he creates female mannequins for the business located directly below his one-room studio. What role will he play in the unfolding drama? Ah, that’s not for me to say, but if you like your noir dark, then what Arita is prepared to do to enrich himself a little later in the story should fill that urge nicely.

There’s an argument for seeing the diamonds that Miyamoto has presumably stolen and wants to sell as the film’s MacGuffin, at least in the George Lucas interpretation of that favourite Alfred Hitchcock term. In Hitchcock’s view, a MacGuffin was something that the antagonists want to get their hands on but the audience doesn’t care about, whereas Lucas believed that the audience should care as much about it as the on-screen characters, and I’d argue that’s very much the case here. Miyamoto initially has the diamonds and wants to sell them and give the money to Mihara, but Ōyane clearly wants them for himself, and he’s the one setting up deal to sell them to a foreign buyer. Yet against all expectations, the sale is arranged as promised on a deserted rooftop, but the deal is hijacked by three masked men before it can be concluded. The robbers attempt to snatch the stones, but before they are able to so… and that’s where complications really set in, and we’re still only at the 18 minute mark here.

I’m sorely tempted to throw up a spoiler warning in order to discuss how events subsequently unfold, but it’s enough for newcomers to know that the quest to own the diamonds ultimately pits Miyamoto against his former yakuza colleagues and eventually sees the rebellious and fiery Akiko reluctantly recruited to his cause. An overheard conversation, to which he knowledgably contributes as a helpful bystander, provides Arita with the information and motivation to take desperate action of his own, and the cat-and-mouse game that results in the gems changing hands or being just out reach is most enjoyably twisty, with the question of who they will ultimately end up in the possession of remaining uncertain until the tightly handled and noir-soaked climactic scene. Mizushima Michitarō makes for a suitably moody Miyamoto, and there are some nicely cast faces in supporting roles, but it’s Shiraki Mari who makes the biggest impression as Akiko, a rebellious free spirit who refuses to conform to patriarchal expectations of how women should look and behave. I learned from the special features that she was formerly a dancer, and that really shows in the lively fluidity of her movement, a key aspect of a performance whose physicality reveals as much about the character as her abrupt switches of mood or her assertive choice of words.

Underworld Beauty was an early gangster thriller from director Suzuki Seijun, who remains most famous in the west for his duo of rule-breaking gangland gems, Tōkyō Drifter (Tōkyō nagaremono, 1966) and Branded to Kill (Koroshi no rakuin, 1967), although thanks to the efforts of both Radiance and Arrow Video, more of his earlier films have since been made available on UK Blu-ray. As the key special feature on this disc ably demonstrates, Suzuki was more than just a director of yakuza thrillers, but it’s a genre in which he repeatedly demonstrated his considerable skill as a cinematic storyteller and stager of tightly structured action scenes. On this score, he’s ably assisted by one-time cinematographer Nakao Wataro (was this really the only film that he shot?), and by insanely prolific editor Suzuki Akira, who ranked up an astonishing 343 editing credits over the course of his 50-year career. Every scene is handled with confident aplomb, and there’s an economy to the storytelling here that occasionally sees entire scenes compressed into a single shot and then rapidly moved on from. A personal favourite comes when Miyamoto is chasing Akiko and corners her in alley, which prompts her to whip off her shoe and smash the glass covering a fire department hose with the intention of using it against her pursuer, which Miyamoto responds to by slapping her face. The film then cuts to an extraordinary, high-angle wide shot of the immediate area in which the surrounding buildings seem to act almost as an architectural iris to focus our attention on the two figures, as they stand off against each other and a police siren rises on the soundtrack. This image then horizontally wipes to a shot of a thoroughly fed-up looking Akiko sharing a police holding cell with four other women (two of whom are arm-wrestling), which then fades down and up to a wide shot of the police station exterior as she exits in Miyamoto’s company, compressing several hours of real-world time into just 30 dialogue-free seconds.

Genre fans will find plenty to get their teeth into here. The thrills are genuinely thrilling, the climax tense, the gangsters tough and morally bankrupt, and the antihero is working for a just and redemptive cause, and is teamed with the sort of feisty and independently minded female lead that was rare in the cinema of any description in its day. The music and dialogue-free shoot-out that builds up to the climax is top-drawer Suzuki, and even prefigures later John Woo actioners at one point when Miyamoto faces off against a small army of yakuza goons with a gun in each hand. I have to admit that the final sequence caught me by surprise, primarily because the lengthy and breathless preceding scene appeared to steering the characters in a different direction. On first glance, this ending may feel out of step with the noir toughness of what has gone before, but as Kodama Mizuki points out in the special features, there’s more going on here than immediately meets the eye.

Sourced from a new 4K restoration of the film by Nikkatsu Corporation, the 1080p transfer on this Radiance Blu-ray is a strong one with the one tiny but justifiable caveat. The first thing I look for when it comes to a Blu-ray release of a black-and-white noir movie is how deeply the blacks are rendered, and while the contrast grading is pleasingly consistent here, the black levels are just a whisper shy of the inky black of gold standard monochrome transfers. There is, I believe, a sound reason for this, which is evident in the visible detail in darker areas that would almost definitely be crushed out of existence if the contrast was boosted to deepen the shadows, and the tonal range is top-notch in other respects, so I’ve no complaints here. Film grain is clearly visible throughout, suggesting either the use of a fast film stock or a source other than the original negative for the restoration, but again this is consistent and never impacts on the picture sharpness and detail definition, which is always impressive. The image is also clean, with only a couple of brief minor scratches and dust blips visible, and while there is some very slight movement in frame on a small number of shots, you’ve have to be looking for this to notice it. On the whole, another very fine job from Radiance.

Love Letter (see below) has also clearly undergone a restoration, and although there are a fair few more dust spots and other small blips of wear here, the resulting restoriation and transfer are of a similar quality to Underworld Beauty.

One point. The aspect ratio here of both films is 2.40:1, which I presume is correct, especially as the restorations were carried out by Nikkatsu, the studio for which the films were originally made, which casts doubt on accuracy of the claim made on the films' IMDb pages that the original aspect ratio of both was 2.35:1.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack shows its age a little more evidently than the picture, with a restricted tonal range that gives louder sounds and dialogue a slightly abrasive feel, and the ringing of a telephone is genuinely shrill if you have the volume cranked up as high as I tend to. There is also some audible background fluff in quieter scenes, something I only really noticed because of the film’s effective use of silence and rationed use of non-diegetic music. No problems otherwise, with the dialogue always clearly audible and the music free of distortion, and I detected no evidence of any damage.

Optional English subtitles are activated by default.

Kodama Mizuki (14:44)

Critic Komada Mizuki delivers an absorbing examination of Underworld Beauty, with particular focus on actor Shiraki Mari and the character of Akiko, and how she differs from the more traditionally demure Japanese norm. This includes some intriguing and even revealing observations about the way that Shikari speaks and moves in the film, how the depiction of women and sexuality in Suzuki’s work has changed over time, and the fact that Suzuki does not portray the female body in a sexual or erotic way. Komada also talks about the film’s final scene, so definitely save this until after watching the film itself.

Love Letter (Rabu retā, 1959) (39:28)

Tōkyō nightclub pianist Kozue (Tsukuba Hisako) lives for the letters she regularly receives from Masao (Machida Kyōsuke), a man that she met and fell in love with whilst visiting the mountains two winters ago. Since then, Masao has been living in his mountain cabin while he recovers from an unspecified illness, but the love that the two share remains as strong as ever and is mutually expressed by them both in their correspondence. Despite this, lonely nightclub singer Fukui (played by popular real-life singer Frank Nagai) is also in love with Kozue and wishes to start a life with her, but despite the appeal of settling down with the man she works with and who drives her home every evening, Kozue remains devoted to Masao.

One night after dropping Kozue off outside her home, Fukui reminds her that she has been waiting for Masao for two years now and suggests that it’s not Masao that she’s in love with but his letters. Yet when Kozue reveals that they have stopped coming and that she’s no longer convinced that Masao is waiting for her, only to then find a new letter from him tucked in her mailbox, the kind-hearted Fukui suggests that she go to the mountains and see him. “If you feel as you do in the letters, then you should be with him,” he tells her. “But if you decide to come back to the club, I’d like to think you were coming back to me,” which prompts a small nod of agreement from Kozue. We don’t get to see what this latest letter says, but it prompts a concerned reaction from Kozue, who jumps on a train and makes her way into the isolated mountain region in which Masao lives. She finds him in the exact same way she did when they first met, but when Masao sees Kozue he reacts with startled surprise and runs away, with the confused and deeply concerned Kozue in hot pursuit.

For those who know Suzuki Seijun primarily for his gangster movies, this 1959 short film, made relatively early in his near half-century long career as a director, may seem like an out-of-character sidestep, but as is pointed out by Suzuki biographer William Carroll in the accompanying commentary, it was anything but. For a good many of us in the west, however (myself included), this 40-minute romantic melodrama is a real eye-opener, and proof positive that Suzuki was more than just a bold and imaginative director of crime-themed thrillers and dramas. Don’t be fooled by the dreamy romantic imagery of the opening shot of Kozue playing piano whilst seemingly floating in a sea of stars, and especially by the flashbacks that visualise her memories of first meeting and falling in love with Masao, as they will later prove to have a specific narrative purpose. And while the early scenes may have a strong whiff of that overly idealised quality that renders so many entries into this genre indigestible to us more cynical viewers, the simple fact that the central romance is already under way and being tested as the film begins gives Love Letter an interesting edge from the off. It really helps that Fukui is not an archetypal scheming scumbag of a rival but a genuinely nice guy who wants whatever is best for Kozue, even if it means losing her to someone else. Yet it’s when Kozue comes face-to-face with the love of her life for the first time in two years that the film moves into another gear entirely, as this formally perfect romance becomes infused with intrigue and doubt. Both we and Kozue know that something is wrong, but not what, and I’m not about to spoil things by revealing how events subsequently play out.

The economy of storytelling on display here can be gauged by the fact that the above detailed setup and more unfolds in the space of just nine minutes of screen time. The filmmaking is assured and intermittently sees Suzuki’s mastery of his craft put to expressive and even inventive use. My favourite moment (and it was nice to see this also highlighted by William Carroll on his commentary track), comes after Fukui has restated his feelings to Kozue and dropped her off at her apartment block, and as the camera tracks alongside Kozue as she walks to her apartment door, she appears to be recycling Fukui’s words in her head and responding to them verbally, only for the viewpoint to then subtly shift to reveal that Fukui is following her, and that the two were conversing with each other after all. I’m sure that my description does not do justice to how sublimely this shot plays. The mystery of what has happened to Masao to damage the previously idyllic relationship he had with Kozue makes for arresting viewing and certainly kept me guessing, and while the explanation, when it comes, is one I had considered but certainly not settled on decisively. Its impact on Kozue also prompts an instant recall to an earlier comment made by Fukui, one that shapes how the story subsequently plays out.

The result is an entrancing, poetically written (by Matsuura Takeo, from a novel by Matsuura Kenrō – are these two related?), skilfully directed, and earnestly performed romantic melodrama with strong production values, built around three genuinely likeable and good-hearted characters and building to a touchingly bittersweet ending. Absolutely full marks to Radiance for snagging this as a special feature. But wait, there’s more…

Audio commentary on ‘Love Letter’ by William Carroll

While it may seem odd that William Carroll, the author of Suzuki Seijun and Postwar Japanese Cinema, has provided a commentary for this short film rather than for the main feature, I get the feeling that he relished the chance to talk about one of Suzuki’s rarely discussed non-gangster movies. Besides, he previously addressed Suzuki’s work in the gangster genre in his commentary on the Radiance Blu-ray release of Suzuki’s 1965 Tattooed Life (Irezumi ichidai). As expected, Carroll really knows his Suzuki films, providing welcome information on the actors, recurring themes, motifs and imagery in Suzuki’s cinema, his creative and purposeful use of editing and framing, and much more. He’s clearly an admirer of this film (no argument here), and had exactly the same reaction to the shot in which Kozue initially appears to be talking to herself as I did. I also salute his respectful use of the Japanese convention of family name first, which I also observe as a matter of course.

Underworld Beauty trailer (3:15)

A structurally untidy but somehow still rather seductive trailer with a small collection of spoilers that flit past quickly but would likely stick in your mind if you watched this just before your first viewing of the film. Best not to, then.

Love Letter trailer (2:54)

A romantic bells-and-whistles Japanese trailer that initially sells the film as a straightforward tale of love and devotion, then shortly before the end does the unthinkable and gives away the film’s late-story twist. My jaw genuinely dropped. Seriously, what were the people who made this thinking? As a result, I’d definitely avoid watching this until after you’d seen the film. That said, I have a feeling that the sometimes almost electrical or cell-like chemical damage to the source material here would have Decasia and Dawson City: Frozen in Time director Bill Morrison jumping up and down with glee.

Also included is a Limited Edition Booklet featuring new writing by critic Claudia Siefen-Leitich and an archival review of the film, but this was not available for review.

A must for fans of the work of maverick director Suzuki Seijun and the Japanese gangster genre in general, Underworld Beauty is a tautly made noir thriller with well-drawn characters and solid performances, including standout turns from Mizushima Michitarō and Shiraki Mari as the intriguingly mismatched Miyamoto and Akiko. The restoration and transfer is up to the usual high Radiance standard, and the inclusion of Suzuki’s 1959 short film Love letter and William Carroll’s informative commentary for the same are a real coup for devotees of the director’s work. Highly recommended.

The Japanese convention of family name first has been used for all Japanese names in this review except for Frank Nagai, which was the adopted and semi-westernised stage name of Nagai Kiyoto.

|