|

Viewing habits and conventions do tend to create certain expectations. If you go to the cinema to see an action movie directed by Michael Bay, you probably do so with a reasonably accurate idea of what to expect. In a stylistically disconnected but thematically similar vein, there's also a good chance that if you sit down for a historical documentary constructed solely from archival stills and footage and talking head interviews then you'll be able to picture in advance the manner in which it will play out – however compelling or revelatory the subject, the format has already been set in stone. The interviewees tell the story, perhaps with a narrator filling in the narrative gaps, their words illustrated by film or video clips and photos that have been treated to what has come to be known as the Ken Burns effect to add a little motion to otherwise static imagery. The result will usually be underscored by a music score whose prime purpose is to influence how you emotionally respond to the material. Perhaps there'll even be re-enactments of actual events, and a popular favourite now when using stills is to separate the subject from the background and move the two components independently to give old photos a faux three-dimensional feel. That's certainly a trick I've been using for some time now.

If I sound a little cynical then I don't mean to be. The reason this approach has endured for so long is that it remains a most effective way of telling a factual story, expert and eyewitness testimony backed by visual and aural evidence. I'd also argue that some of the very best documentaries you're likely to see have adopted this very approach. Every now and then, however, one comes along that takes this formula and plays with it to mesmerising effect. Enter filmmaker Bill Morrison, whose fascination with damaged and degraded film gave birth to the 2002 Decasia, an audio-visual assault on the senses that remains one of the most brain-battering experiences I've ever had in a cinema. In Dawson City: Frozen Time he may be telling a narratively-driven factual story, but the subject matter allows him to revisit territory explored so captivatingly in that earlier film.

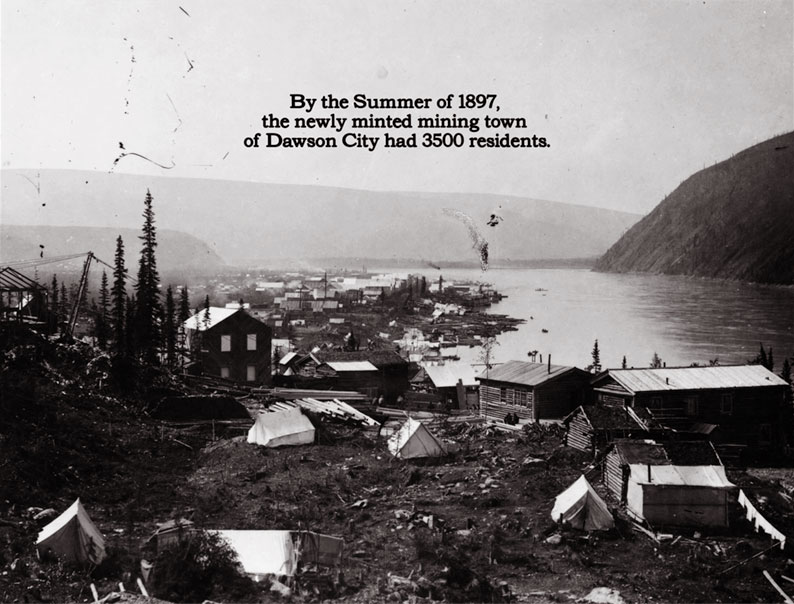

The Dawson City of the title is a town in the Yukon territory in Canada, 350 miles south of the Arctic Circle. In 1978, when ground was being excavated in preparation for a new construction, a treasure trove of old nitrate cine films was unearthed, which had been partially preserved by permafrost and which included many titles that had long since been thought lost. With the aid of clips from these films, Dawson City: Frozen Time chronicles the founding and development of the town through its population explosion during the Klondike Gold Rush in the late 1800s up to the discovery of the buried film reels almost a century later, in the process revealing how and why these films – which came to be known as the Dawson City Collection – came to be there in the first place.

Structurally, the film kicks off with what may or may not have been intended as a sly bit of misdirection, with a short extract from a talk show on which Morrison is interviewed about the Dawson City films, which is followed by what appears to be archive footage and stills of their uncovering and a standard two-shot interview with key players in the story, Michael Gates and Kathy Jones Gates. This gives the impression that we're about to watch a solid, by-the-numbers documentary in the mode outlined above, but it's actually more an introduction, a traditionally framed and structured gateway to an altogether more adventurous work. Immediately after this, we're whipped back in time to the recount the evolution of nitrate film, which was developed almost as a by-product of an explosive known as gun cotton, a substance I am familiar with thanks to a friend in my younger days who tried making it himself by stealing acids from the school science laboratory. The film then explores the history of Dawson City in considerable detail, from its foundation to its rapid, Gold Rush-inspired expansion and later population shrinkage when there were no new mining claims left to make, and news reached the town of gold strikes elsewhere.

The story, which was clearly researched in considerable detail by Morrison and his collaborators, is a fascinating one peppered with unexpected connections. There surely can be few who were not aware that the writings of Jack London were inspired by his ill-fated trip to the Klondike, but it's almost too perfect that a young Sid Grauman – he of Grauman's Chinese Theatre on the Hollywood Walk of Fame – saw his first moving picture in the very location that so many of the films from his time there would later be unearthed. Other Dawson residents of this period who later achieved fame included photographer Eric Hegg, who created some of the most iconic images of the Gold Rush, and Alex Pantages, a bartender who went on to become one of first great movie tycoons with an empire of 70 theatres across North America. And let's not forget the Arctic Hotel and Restaurant in nearby Whitehorse, a brothel built by a certain Fred Trump that was the origin of the current American president's family fortune.

The story has so many interesting threads that some of those worthy of further exploration receive what initially feels too brief a mention, notably the forced relocation of the native Hän tribespeople and the destruction of their fishing and hunting grounds by companies and individuals digging and dredging the area for gold. This does, however, avoid overstating points that are instead made almost slyly, as with the way the various mining claims are gradually consolidated into a handful of companies and eventually a single corporation, which industrialises the process of extracting the precious metal from the ground to such a degree that all competition is effectively wiped out. The story is also peppered with fascinating asides and eye-opening revelations that I'm not about to spoil here, save to say that the one involving Irene Caley and Will Crayford and their desire to build a greenhouse scarily demonstrates how easily great works of art could be (and doubtless have been) lost.

The story alone would make for compelling viewing, but what lifts Dawson City: Frozen Time onto another level entirely is the bewitching manner in which it is presented. Forsaking the traditional approach of using interviews and/or a narrator to tell the story, Morrison employs captions that fade up and down over clips from the Dawson City Collection, coupled with archive photos and extracts from Chaplin's The Gold Rush and a sprinkling of other films, all carefully selected to illustrate the specific aspect of the story being told. This film footage is drawn from a variety of sources, including short dramas, comedies and newsreels, but used as it is here it plays like documentary material, providing visual evidence of historical facts that are superimposed over it in textual form. There was clearly a rich pool of material to draw from here, so rich in places that I couldn't help thinking that some sequences run longer than others purely because Morrison was able to find so many clips that revolved around a particular theme. Usefully, every one of these extracts is also captioned with the title of the film from which it is taken, together with the date of production and whether it was part of the Dawson City Collection, small-fonted text that sits unobtrusively in the corner of screen for the interested to take note of and others to easily ignore and focus on the image if they prefer. Later, the scope expands to include world events that were chronicled in the unearthed newsreels, some of which have proved to be important finds.

The most distinctive aspect of the film, however, is how Morrison, composer Alex Somers and sound designer (and Alex's brother) John Somers transform what is essentially a historical documentary into an artistically thrilling audio-visual experience. Indeed, the score and the imagery become so wedded to each other that it becomes hard to imagine experiencing one without the other. As scores go, Somers' is up there with Michael Gordon's for Decasia, shifting effortlessly from the harmonious to the avant-garde, able to evoke a sense of wonder without dipping even the smallest of its toes into musical cliché, then transforming to infuse the more spectacularly damaged imagery with the air of twisted nightmare, one that could chase you fearfully into the waking world. Intermittently, this wedding of water-damaged imagery and sensory-assault sound peaks to an artistic umbilical cord that leads straight into Decasia's womb, utterly thrilling semi-abstract interludes that if played on a loop simultaneously on four walls of a gallery at high volume would have the potential to drive a sensitive viewer insane.

Equally impressive is John Somers' sound design, which underscores the music with sounds associated with the on-screen activity instead of attempting to create a false synchronised soundtrack in what has become the traditional manner. The sound here never masquerades as the actual soundtrack of films that we know were shot silent, instead evoking a strong feeling of the locale or the action, but mixed at a low enough volume to do so unobtrusively, creating a background track that never does battle for dominance with the music and that you absorb rather than listen to the specifics of. Somers also employed a computer program to create electronic sounds from the water damage, which when matched to the film elements from which they were drawn seem to infuse the destruction with organic life and help to highlight and celebrate material that other filmmakers would do their best to disguise or reject outright.

There really is so much to admire and absorb here and I've only really scratched the surface of what this remarkable film has to offer. If this was just a documentary portrait of town and the surrounding locale, or an investigation into the discovery of the buried film reels and how they came to be there, or a semi-abstract expressionist painting made with sound and decayed film in the manner of Decasia, then it would, I believe, still be worthy of considerable attention and praise. Dawson City: Frozen Time is all three of these things combined into a single immaculately crafted and artistically thrilling whole. I loved every gorgeous second of it.

Just how you accurately judge the quality of a film comprised almost entirely of damaged archive footage is a question that has come up before on this site, and the answer is always that you do so by looking at the best quality material the film has to offer. In the case of Dawson City: Frozen Time, the obvious choice is the interview with Michael Gates and Kathy Jones Gates, with was shot specifically for the film on what was likely HD video. Yet for me it was the brief extracts and outtakes from Wolf Koenig and Colin Low's 1957 short film City of Gold that are the standard-setters here, boasting a lovely monochrome tonal range, a striking level of detail, and no signs of wear and tear. There is inevitably some considerable variance in the rest of the material depending on the degree of damage that the clip in question has suffered, but intermittently the quality really jumps out at you. The black-and-white photographs taken by Kathy Jones Gates when the Dawson City films were unearthed look amazing. Pleasingly, the film is presented in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio of the Dawson City films, which are not cropped to fill a 16:9 frame as some filmmakers are unfortunately wont to do.

When it comes to the soundtrack, there are two options available, Linear PCM 2.0 stereo and DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround, and while the stereo track is first-rate, if you have a DTS sound system then you absolutely have to run the film with that soundtrack enabled and crank the volume up high. This is beautifully recorded and mixed track, crystal clear in is detail and with LFE bass work that rattles the sternum, all the while making encompassing use of the surrounds to place you in the midst of the film's extraordinary soundscape. Indeed, so effective is it that I will go out on a limb and suggest that unless you see the film in a cinema with a first-class sound system or have a good surround (and preferably DTS) system of your own on which to experience this disc, you'll be losing out, just a little.

Surprisingly, given that the film is primarily caption-driven, optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired have been included, primarily for the opening interview material.

Interview with Bill Morrison (21:45)

A welcome interview with director Bill Morrison, who talks about his journey from painter to filmmaker and reveals how a screening of Decasia in Ottowa hooked him up with the man who first introduced him to the Dawson City films and effectively launched this project. The slow process of working through the films and eventually scanning them in 4K to an army of hard drives is detailed, as are some key specifics of how the project developed, including the cooperation Morrison received from Michael Gates and Kathy Jones Gates and the composition of the score by Alex Somers, whose brother John was responsible for the film's sound design. Morrison's comments on the appeal of damaged film are of particular interest, and he highlights the irony of how an attempt to dispose of so many films ended up preserving them.

Dawson City: Postscript (9:54)

This short piece, also by Morrison and featuring more of the interview with Michael Gates and Kathy Jones Gates and footage shot of the original restoration process, is indeed a postscript to the main feature, being comprised of material that I'm guessing just couldn't be shoehorned into the film without disrupting its flow and tone but is well worth seeing nonetheless. The volatile nature of nitrate film stock is brought home again in the news that 800,000 feet of March of Time newsreel outtakes were destroyed in a single fire and that an explosion in 1978 destroyed a horrifying 13 million feet of film. There are also a few shots of Dawson City as it is today, if you're curious.

The Letter (12:32)

In the interview detailed above, Bill Morrison states that he will continue to use the Dawson City footage for the rest of his life, and he gets off to a robust start with this arresting short constructed from extracts from several of the Dawson City films, all which revolve around reading of letters. As with Decasia, to which this film is stylistically and artistically bonded, the water damage becomes a character in the film and transforms narrative sequences into moving abstract expressionist paintings, and in two close-up shots the damage is so extensive that the letter that fills the frame oscillates and pulses like a living organism. Innocent actions are given a sinister makeover by the decay and Ricardo Romaneiro's brain-bending score, and there are moments that have the disturbing air of a Lynchian horror movie.

Trailer (2:09)

A solid enough trailer that gives a flavour of the film's style and content, using its music and graphics and not trying to hide the fact that some of the film is in a seriously damaged state.

SELECTIONS FROM THE DAWSON CITY FILM FIND:

A selection of short films and newsreels from the Dawson City Collection, all of which are incomplete and are usually missing their endings, which can be a tad frustrating in the case of the narrative dramas. All display damage, which tends to increase – sometimes dramatically – as the films progress.

British Canadian Pathé News 81A 1919 (12:23)

This was one of the major discoveries of the collection, including as it does footage of the World Series baseball final between the Chicago White Sox and the Cincinnati Reds, a game that was later revealed to have been thrown by the White Sox players for money in what remains the worst case of game fixing in baseball history. It did, however, give rise to two excellent films in the shape of John Sales' Eight Men Out and Phil Alden Robinson's Field of Dreams. There are shorter pieces on the Dublin Royal Horse Show, some royal dude inspecting a Vancouver saw mill, and an unlikely looking motorised plough that somehow just never caught on. Most disturbing is the aftermath of a riot that saw demented racists (is there any other kind?) wreck a courthouse in their efforts to hang a black prisoner, and the Trump era is foreshadowed by a story about Judge Elbert H. Gary, who refuses to arbitrate a strike with union representatives at a steel mill owned by the corporation he just happens to be head of.

International News Vol. 1, Issue 52, 1919 (11:11)

This newsreel includes footage of tobogganing families in snowy California (part of which is run in reverse for the fun of it), a hero's welcome given to French boxer Georges Carpentier when he returns to home turf after beating his British rival by knocking him out in a ludicrous 70 seconds, floodwaters in the Philippines, and a fire at the Solax Film Laboratory. There's a tabloid whiff to the glee with which the newsreel observes and comments on the deportation of ‘red' agitators, though the most valuable find here has to be a story on the world water speed record holding craft known as The Flying Fish, which includes very clear footage of telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell at the controls.

The Montreal Herald Screen Magazine 1919 (12:26)

The first story in this rather parochial newsreel is more interesting for its technique than its content, as designer Hy Mayer's stop-motion fashion drawings are match-cut into live action footage of the same, a technique that was genuinely advanced for its day. There is also a comical piece on characters that are always in the public eye, another involving a baby modelling hats, and a series of textual gags that were probably funny in their day. There's also a POV ride down a water chute that appears in the feature, which is plastered with interesting damage, and by the time we get onto a story about a pet hospital it has overtaken the image. There's even a bit of Claymation on the final, hardly visible story about mud sculptures.

Pathé's Weekly #17, 1914 (8:59)

This newsreel has stories on the launch of the largest American oil tanker, King Constantine of Greece paying a visit to the newly annexed Crete, quarry dynamiting in California, a suffragette pantomime, public displays to mark the Kaiser's birthday, and a single shot of outdoor amusements during a particularly severe Berlin winter. We are shown a new horticultural building in San Francisco that a caption assures us is “near completion” (it bloody well isn't), while an opening piece on the mobilising of American forces after the killing of William S. Benton on the orders of Pancho Villa has footage of horseback manoeuvres that is genuinely epic in scale and looks almost like extracts from a big-budget D.W. Griffith war movie.

The Butler and the Maid, Thomas A. Edison Inc., 1912 (2:50)

A butler gets sniffy at a maid for getting friendly with the delivery boy then refuses to take her to a ball to which he has an invitation. He's then visited and bewitched by what looks like a living statue, though it's a while before we see her as she's initially wrapped in a ball of spectacular and wildly animated water damage, which gives her appearance before him an even more supernatural feel. The two step outside and end up being chased by a policeman, but the reel ends before with find out why or what happened to them.

Brutality, D.W. Griffith, Biograph Company, 1912 (10:25)

A young woman falls for a man she meets and flirts with when he passes her house, and despite being shocked by his angry response to being bumped into in the street (he beats the other man silly), she foolishly marries him. It's not long before he's drinking and treating her like crap, but one evening the two attend a stage production of Oliver Twist and see their marriage reflected in the abusive relationship between Bill Sykes and Nancy... and that's where the only recovered reel of this short drama comes to an end. Intriguing to see a film about spousal abuse made so many years before it became a staple of social realist cinema, and the director credit alone makes this of interest. Research suggests, by the way, that watching the play prompts the man to mend his wretched ways. To quote Hail, Caesar!, would that it were so simple.

The Exquisite Thief (reel 2), director, Tod Browning, Universal Film Manufacturing Company Inc., 1919 (8:20)

Reel 2 of a 1919 short film directed by Tod Browning of Dracula and Freaks fame is a serious tease. It tells the story of a male and female robbery team that raids a plush dinner party hosted by a man named Lord Chesterton, who as the reel begins has been handcuffed to the banister by the male half of this duo while his partner robs the guests. When they get away, Chesterton and two of the guests give chase, and Chesterton eventually ends up a prisoner of the bandits. He clearly has a plan to escape their clutches, but frustratingly the reel ends before he puts it into action. Still really worth seeing for the filmmaking alone, particularly the creative use of lighting in the car chase and on the landing of the criminals' hideout.

The Girl of the Northern Woods, Thanhouser, 1910 (6:21)

A local letch comes aggressively on to the girl of the title, who firmly resists him and instead falls for a visiting surveyor, whose assistant is set up to be the film's comic relief but is killed by a gunshot from the letch that was intended for the surveyor, who is then framed by the letch for the killing. Once again, the ravages of time have robbed us of the ending, albeit one you should be able to make an educated guess at, and I can't be the only one that winced a little at the suggestion that the letch behaves the way he does because he's a 'half-breed'. The damage isn't as bad as on some of the other films but the image is more washed-out here and plastered with scratches.

Booklet

This contains an excellent and considered essay on the film by Gareth Evans (the London-based writer, film and event programmer, not the director of The Raid), who examines the film in more detail than you'll want to absorb before your first viewing but will appreciate after you've seen it. Impressively, he also discusses a few areas in which he believes the film falls short or misleads its audience in regard to the Dawson City films and their (comparative) importance. This makes for fascinating and educational reading and should be considered an essential companion to the main feature, as it fills in some considerable gaps about the rescue and restoration of the Dawson City films.

Rarely if ever have I seen documentary filmmaking and arthouse experimentation work in such perfect harmony as it does in Bill Morrison's Dawson City: Frozen Time. It's a film that fascinates and educates as it aurally and visually thrills, a detailed history lesson passed through the lens of a visionary artist that manages to be simultaneously challenging and accessible. Serious family illness has delayed this review, which would have taken a while anyway due to the sheer volume of fascinating material on this excellent Blu-ray, which for me is one of Second Run's best yet and gets our highest recommendation.

|