|

I can't say for sure whether filmmaker Bill Morrison is fascinated by decay in general, or just by how it can transform the celluloid image, but there is absolutely no question that he is compelled by the latter. This was established with mesmerising aplomb in his experimental 2002 feature Decasia, which was constructed entirely from a diverse range of nitrate film clips in various stages of decomposition, and had the balls and the vision to make that damage the film's raison d'être. In 2016 he adapted this technique to the documentary format for Dawson City: Frozen Time, which tells two directly connected stories. The first is of the uncovering of a sizable collection of old nitrate films in the Yukon town of the title, while the second explores the history of the town itself using clips from the uncovered films, which despite being largely preserved by permafrost were in various states of decomposition. The resulting film is a spellbinding mix of documentary and arthouse experimentation that was one of my picks of the year for 2019 when it was released on Blu-ray that year by Second Run. Five years on, the label has done likewise for Morrison's latest feature, The Village Detective: a song cycle, which has much more in common with Dawson City: Frozen Time than the colon that sits midway through its title.

The project was initiated by a friend of Morrison's, the late great Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson (he of Prisoners, Sicario, Arrival, Mandy and others), who in July of 2016 sent Morrison an email that included the following message:

A friend told me about some film cannisters containing an old Soviet film that were caught in the net of an Icelandic trawler. Apparently the cannisters are being stored in an Icelandic film archive. I thought you might be interested…

I'm not sure exactly how Morrison first responded on reading this, but based on his previous work, there's a part of me that can't help thinking that something inside him screamed "Hell, yes!" The canisters in question contained four reels of nitrate film and they had been sitting on the seabed near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge for decades, a potential volatile volcanic location that is rich in hydrogen sulphide, which is apparently also rather good at preserving materials that might otherwise perish in salt water. The film reels were placed in the care of Erlendur Sveinsson, the then Director of the National Film Archive of Iceland, and the discovery proved of interest to the Icelandic nation broadcast news channel Rúv Fréttier, which handily provides Morrison's film with an interview with one of the fisherman, and footage of Sveinsson examining the film and carefully unspooling it onto sheets of newspaper spread out over the archive floor. It turns out that the rescued reels contain a Russian film from 1969 titled Derevenskiy detektiv – which translates as The Rural Detective or The Village Detective – and it's Sveinsson who on camera spots that the cast is headed up by Mikhail Zharov, an actor who was hugely popular in Soviet Russia but is little known in the West. Having travelled to Iceland to interview Sveinsson, an intrigued Morrison thus then heads east to Gosfilmofond, the Russian state film archive in Belye Stolby, to discover more about the film career of this celebrated actor.

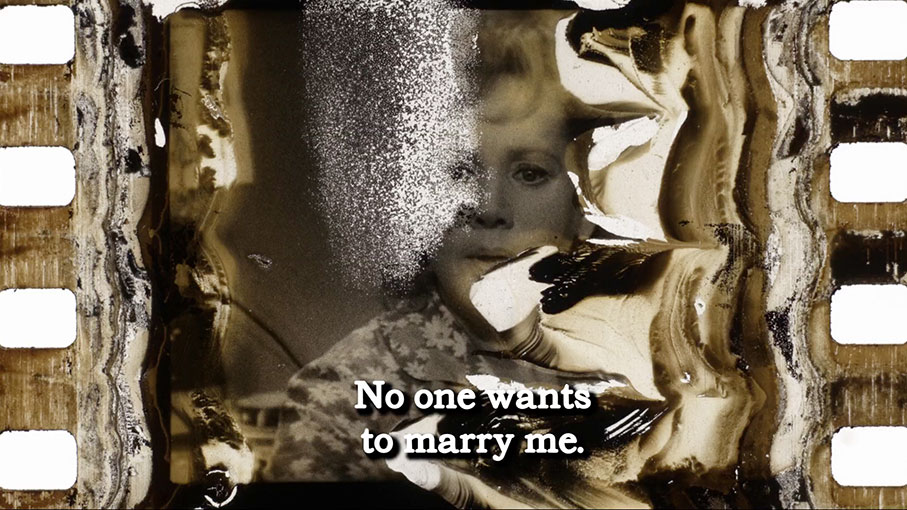

The film then divides into two stylistically different halves of a story that has Mikhail Zharov at its core, an approach that casts Morrison alternately as a film historian and an artist with a fascination for decaying film. In the former role, he sources a string of illuminating clips from Zharov's filmography (the titles of which are always identified by small captions at the top right of screen) to explore the career of one of his country's most beloved actors and lost early films of Soviet cinema. Contextual commentary is provided by captions, plus a useful interview with Peter Bagrov, a former curator at Gosfilmfond and the current curator of the George Eastman Museum in America. This alternates with sometimes lengthy extracts from the recovered print of Derevenskiy detektiv, whose presumably unusable optical audio track is replaced by an almost mournful, accordion-driven score by composer David Lang, the absent dialogue presented as translated English subtitles. Here Morrison really is in his element, lingering on the images for many minutes at a time, seemingly less for the narrative of the film than the sometimes abstractly striking dance of decay that has been wreaked on it by its years on the ocean floor.

The presentation of these clips differs from the established norm. By running the film slower than itts normal projection speed, Morrison also allows each iteration of decay to to more fully register instead of just flitting past, and although the print is framed 1.37:1, he makes full use of the widescreen aspect ratio here by including the optical soundtrack and projection sprockets, both of which have also been impacted by undersea wear. Intriguingly, at one point the image begins slowly rolling upwards to reveal the top of the frame beneath, a process we follow until it eventually completes its circuit round. This would usually only occur as a projection issue, and I initially suspected that its inclusion here was due to some creative tinkering on Morrison's part. In the special features, however, he reveals that it was a most unusual – and in his words, "very beautiful" – fault with the print itself, one that may even have been the reason it being discarded from the ship on which it was carried as entertainment for the crew.

Although at times it can feel as if you're watching two very different films that have been spliced together into one, there's a layering here that binds them and proves increasingly intriguing, especially for first-time viewers unfamiliar with the work of Mikhail Zharov. Repeatedly, the film's approach and structure become reflective of the content, often in ways that only resonate towards the very end. It's a similar story with Derevenskiy detektiv and its tale of a rural policeman's search for a missing accordion, which triggers Morrison's own investigation into the actor who plays the investigator of the title. The effectiveness of this detective story approach relies in part on the fact that, despite his considerable fame on home turf, a good many of us (myself included) will be unfamiliar with Zharov's work. As a result, there's initially a strong sense that this decayed print of Derevenskiy detektiv is a major discovery, the only surviving copy of a long lost work of one of Russia's most celebrated actors. Gradually, however, there are small signs that not all may be what it first seems. My first inkling came when an early clip of the corrupted visuals is accompanied by a synchronised dialogue soundtrack that is strikingly clear and free of wear. How, I wondered, could an optical soundtrack that we can clearly see is as blighted with damage as the visuals have been so immaculately restored? Following this, the soundtrack is largely replaced by David Lang's score, and embedded English subtitles are used to translate the unheard dialogue, which had me questioning how Morrison could have known what the actors were saying if this was truly a lost film. Had a script been recovered and translated for this purpose? The answer comes late, and does not in any way invalidate the intrigue created by what has gone before.

Anyone familiar with Decasia or Dawson City: Frozen Time will be fully aware of Morrison's long-standing love affair with decayed film, and should thus not be surprised by his fascination with the partially decomposed remnants of the recovered celluloid here. Come to The Village Detective: a song cycle without that foreknowledge and expecting a documentary on actor Mikhail Zharov and you'll get what you paid for, but you may also be left a little bemused by the amount of screen time that Morrison devotes to clips of the severely damaged print of Derevenskiy detektiv. The story told within this film-within-a-film is certainly of interest, but does play second fiddle to the condition of the print, as characters are distorted and enveloped by a beguiling variety of celluloid decay, which at times seems to interact with and overwhelm the image in ways that prompt the imagination to run wild and create new stories from the resulting semi-abstract visuals. As with Dawson City, the process of discovery proves as captivating as the story, and provides gallery space for the ever-changing and oddly spellbinding abstractions gifted to the recovered film stock by the unknowingly creative forces of nature, with which Morrison clearly has an extraordinary affinity.

It may seem like a tricky call to judge the image quality of a film comprised largely of archive film clips and severely damaged footage, yet even in those sequences the impressive nature of the 1.78:1 framed, 1080p transfer on this Blu-ray shines through. The benchmark material here is theoretically the new HD interviews shot by Morrison of Erlendur Sveinsson and Peter Bagrov, yet ironically the image sharpness is most clearly evident in the decayed print of Derevenskiy detektiv, where the sometimes spectacular decay is so crisply rendered it could almost have been drawn with ink and fine-nibbed pen. Colour is very cleanly rendered when it appears, detail is well defined even in archive clips, and the contrast is impeccably pitched. An excellent job.

The soundtrack is a full DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix, though unsurprisingly only David Lang's music score makes full use of the surrounds. As you'd expect from a modern digital mix, the music and interviews are both crystal clear, with only the older film clips having the expected restrictions in tonal range.

Given the content, the caption-driven narrative, and the fact that the Russian film clips and the Icelandic news report have embedded English subtitles, it's perhaps no surprise that no subtitles have been provided for the hearing impaired, though I do feel they could still have been useful for the albeit brief interview material.

Interview with Bill Morrison (16:52)

A most welcome interview with the film's director, in which he recalls how the project came about, and early on reveals a fact about Derevenskiy detektiv that his own film effectively keeps under wraps until late in the run time. He talks about researching the career of actor Mikhail Zharov and encountering films that were previously unknown to him, breaks down the full meaning of the film's title, and discusses the decision to have an accordion-based music score, how he develops his film projects, and why this one is structured the way that it is.

The Unchanging Sea (2018) (30:00)

The discovery of a worn print of D.W. Griffith's 1920 silent short The Unchanging Sea in the nitrate vaults of the Library of Congress proves the leaping-off point for one of Morrison's experimental explorations of the beguiling abstractions of decayed film. Here he uses extracts from a range of similarly damaged film works from the era to create a new narrative, one that intermittently plays as if individuals from different realities and timelines are meeting and interacting on what looks like – but almost definitely isn't – the same stretch of shore, or for one section the sea beyond. The result is narratively fragmented enough to require some audience imagination to shape into a coherent story, one that the clips that bookend the film suggest may be the dream of a sleeping woman. Of course, what really defines this as a Bill Morrison work is its open celebration of the ever-charging film decay, which intermittently overpowers and even obscures the image in an often hypnotic moving action painting that casts Morrison as the Jackson Pollock of experimental cinema. As it was with Decasia, the damage is at its most startling when seeming to interact with the photographed image, at one point having the aura of an interdimensional portal into which one of the female characters then steps and becomes completely absorbed by. The connection to Decasia is cemented by a thundering, piano-driven score by composer Michael Gordon, whose music for the earlier film proved so overpowering for a friend of mine that it led to her having to leave the cinema.

Beyond Zero: 1914-1918 (2014) (40:36)

An earlier work along the same lines as The Unchanging Sea, again constructed from decomposing 35mm nitrate footage, Beyond Zero is built exclusively from material shot during the First World War and is set to a score by Serbian composer Aleksandra Vrebalov, one commissioned and performed by the Kronos Quartet. The clips are connected by a loosely defined narrative that begins with parades and departing troops, then builds to imagery of battlefield conflict, air warfare, and injured soldiers being transported to ambulances, but is once again as much about the condition of the clips as their historical content. Some of the damage here is genuinely spectacular and surprisingly varied, as if each example was the work of a sperate abstract artist, with each drawing inspiration from a different source, from plants and cells to fractals and the pattern made when droplets of liquid collide with a hard surface. Intermittently, the decay seems to interact with or inadvertently comment on the subject being filmed, as in the explosions of colour that stand in for exploding artillery shells or anti-aircraft fire. In one astonishing image, a bonfire becomes an epicentre of damage that distorts and melts the image as if radiating a terrifying demonic power. This is at its most effective when working in troubling harmony with the haunting and often disconcerting score, a matching of abstract image and sound that at its peak gives the electrifying harmony of music and imagery in Godfrey Reggio's Koyaanisqatsi a run for its money.

Sunken Films (2020) (10:49)

This 1915 short film by Morrison begins with rare footage documenting the departure from New York of the ocean liner the S.S. Lusitania, a voyage that ended tragically when the ship was sunk by a German U-boat with the loss of 1,199 passengers and crew. This launches Morrison on another intriguing cinematic journey that ultimately leads him to the 1958 documentary Lenin is Alive, which includes footage of Vladimir Lenin shot in 1919 and 1920, clips from which are incorporated into The Village Detective. In common with Derevenskiy detektiv, this footage was recovered by chance from the seabed, this time by Danish fisherman Lauge Iversen in 1976. Unlike the other short films on this disc, the film damage here proves secondary to the historical interest of the films and the voyage of discovery they led Morrison on.

Let me Come In (2021) (10:35)

Sequences from a decayed nitrate print 1928 German film Pawns of Passion [Liebshölle] are cut to an operatic song composed by David Lang and sung by Angel Blue to create a new story, one in which the film damage is once again as much a character as the unnamed male and female protagonists. As ever, the decay has a mesmerising beauty (how appropriate that Morrison's film company is name Hypnotic Pictures), as it tugs at and distorts the image and intermittently overwhelms it in an ever-changing dance of eye-popping abstractions.

Trailer (2:12)

A straightforward trailer that communicates the essence of the film as a portrait of actor Mikhail Zharov whilst remaining cautious about its more avant-garde components.

Also included is the usual Second Run Booklet featuring an essay on the film by writer and film historian Peter Walsh, and it's an excellent one, covering the film in way more depth than my comparatively anaemic scribblings above.

If you've not seen any of Bill Morrison's previous work and are looking for a user-friendly entry into notion of celluloid decay as abstract art, my pick would still be Dawson City: Frozen Time, in part for the scale of the story it tells and the sheer variety of imagery incorporated. Having said that, I'd still strongly recommend The Village Detective: a song cycle, as much for what it reveals about the life and work of an actor I was previously unaware of as for its celebration of the strange but captivating beauty of film decay. The transfer on Second Run's Blu-ray is absolutely top-notch, and the inclusion of the Morrison interview and four of his short films makes this a seriously high quality release, and a must-have for fans of Morrison's previous work. Not for everyone, but this still come highly recommended.

|