|

It's probably fair to say that a sizeable number of UK film fans discovered Japanese director Suzuki Seijun through his stylish late 60s cult double of Tokyo Drifter [Tôkyô nagaremono] and Branded to Kill [Koroshi no rakuin]. I certainly did. Both had me aching to see what other cinematic wonders this director had been responsible for, but getting access to them in pre-DVD UK was a monumental task. My enthusiasm was also tempered by the news that these genre-bending films resulted in him being fired from Nikkatsu, which obliquely suggested that they kicked against a studio line that Suzuki had probably been toeing until that point.

Except he hadn't. I soon realised that films as rule-breaking and imaginative as Tokyo Drifter and Branded to Kill couldn't have just came out of nowhere, and read later that it wasn't one specific film that lost Suzuki his job, but that Branded to Kill was the final straw in what was seen by the studio as a string of creative misdemeanours on Suzuki's part. Now I was really interested in seeing more.

My appetite was further whetted in 2014 with Eureka's Blu-ray release of Suzuki's Youth of the Beast [Yajū no seishun], a film that the director himself once claimed was the first real Suzuki Seijun movie. Then in February of this year, Arrow released Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years Vol. 1 – Seijun Rising: The Youth Movies, a dual format box set containing five examples of Suzuki's pre-Tokyo Drifter work for the Nikkatsu studio, all of which were appearing on home video for the first time outside of their native Japan. For me, this should have been a dream box set that I pounced on immediately, but as site regulars will probably be aware, its release coincided with a traumatic period of my personal life, one that forced me to pass on a number of the releases that I'd normally have covered, this one included.

This follow-up set, was slated for an April release, and this time the review discs were sent to me, and despite the deepening of my family trauma, I somehow found moments here and there to watch the five films, and fired up by what I'd seen I began writing short reviews of each (well, short by our standards, at least). This all came to a grinding halt when my family trauma dissolved into tragedy, and apart from a little administrative work on the site, I put all my pending reviews on hold to focus on what really mattered to me at that time. As I gradually began to climb back into the writing saddle, I was bugged by the fact that this review had been abandoned in a half-finished state, so despite the fact that I'd missed the release date by almost a month (it's just over a month now), I became determined to see it through to completion.

And so, to the films.

| Eight Hours of Terror / Hachijikan no kyôfu (1957) |

|

There's probably an official name for the subset of the drama-thriller in which a group of people from differing backgrounds and with varied personalities and backstories find themselves trapped in a moving vehicle in which they are then subject to threat or danger, and a subset of that in which the location in question is a vehicle on the move. No, I'm not talking about mega-budgeted disaster movies. Think instead Hitchcock's The Lady Vanishes or even Andrei Konchalovsky's Runaway Train, which, lest we forget, was based on an original screenplay by Japanese maestro Kurosawa Akira. In Suzuki Seijun's sensationally titled Eight Hours of Terror (an accurate translation of the original Japanese title, Hachijikan no kyôfu), the vehicle in question turns out to be a bus. It would have been a train, but a landslide has apparently blocked the track ahead, and the throng of agitated passengers are given the choice of either waiting for the track to be cleared or making the journey to Tokyo on a rickety old bus along a dangerous mountain road that has a sheer drop on one side. In the end, only those with an urgent reason for catching the connecting Tokyo train get to board the bus. I've little doubt that those who stayed and waited for the track to be cleared would later reflect on the wisdom of their decision.

As we're introduced to the characters through a series of unfussy shortcuts, the film exhibits the sort of no-frills charm that also characterised the opening scenes of The Lady Vanishes, one that has sadly been lost with the passing of time and the subsequent evolution of cinema storytelling. Each is established with the minimum of fuss and a lack of depth that really doesn't matter here. There's a businessman who cares little for the welfare of others, particularly if it means any delay in the journey; a star-struck girl who is travelling to Tokyo for an acting audition; a left-wing student desperate to attend a meeting that he claims is essential for the country's future; a headstrong young woman who proves to be smarter and bolder than any of the men; a travelling salesman who sells women's lingerie; and an ex-army medic who murdered his wife and her new lover on his return from the war as a decorated hero, who is being transported in handcuffs by a police detective. And that's just a sampling. It might sound from that list as if the obvious source of the promised 8 hours of terror would be the on-board criminal, but even before the bus departs we're clued in to who the real antagonists will be with the announcement that two dangerous bank robbers are on the run and known to be in this area. You don't think they'd somehow get aboard the bus, do you?

Initially, the journey comprises of often lively interactions between the passengers, but things take a sideways turn when they stop to rescue a woman who has thrown herself into a lake because she believes her baby has died. It proves to be a misconception on her part that allows the film to convincingly humanise the prisoner (to whom we are already sympathetic due to the judgemental nature of the other passengers when they discover his story in a newspaper article), as he draws on his former profession in an attempt to save the child's life. By then, the passengers have become a small community, chatting cheerily to each other, sharing food and drink and even singing a rousing song to lend moral support to the prisoner's tireless efforts to save the baby. This is all then thrown into disarray by the inevitable appearance of the aforementioned bank robbers, who hijack the bus and violently threaten its passengers. And while their aggression has an exaggerated quality, their volatility and unpredictability do make them a genuine threat, and the sense that any one of the passengers could meet an untimely end at any moment helps build a level of tension that hangs over the film from this point on. The danger that the two men represent is most vividly illustrated when the bus is stopped by the police and one of the criminals ensures the cooperation of the passengers by holding a gun to the baby's head, a still-jarring image that you can't help suspecting would have been unimaginable in a British or American film of its day.

The subsequent journey is peppered with surprises, including a nail-biting act of bravery by a character that the other passengers then pass unreasonable judgement on when they discover something about her, but who forms a bond with the prisoner in a manner that can't help but prefigure a later one between Leigh and Napoleon Wilson in John Carpenter's Assault on Precinct 13 – the prisoner even makes first contact with the woman when he asks her for a smoke, and their growing friendship develops on similar lines to that in Carpenter's film. And despite early indication that the bus is loaded with archetypes, the characters here do not always follow the expected arcs, as political principles give way to avarice and ineffectual bluster evolves into unexpected action.

The result is a briskly paced, often gripping and consistently enjoyable drama that really showcases Suzuki's talent for economical storytelling and shines in its character detail and the unexpected turns the story sometimes takes. It also, in its way, has an even more international feel than some of the ‘borderless action' films Suzuki was later to make. Indeed, I would argue that Eight Hours of Terror is really only identifiable as a Japanese film at all due to the nationality of and language spoken by its characters, but as a film entertainment it really delivers, and for my money gives some of its more prestigious western genre equivalents of the era a serious run for their money.

| The Sleeping Beast Within / Kemono no nemuri (1960) |

|

Having concluded a lengthy business trip to Hong Kong, middle-aged salaryman Ueki Junpei returns home to the prospect of an ignoble retirement, the result, in part, of being an honest working man who chose not to play the sort of office politics that enabled some of his colleagues to progress to higher things. He's met at the port by his wife, a small group of low-level company men, his devoted daughter Keiko (Kazuko Yoshiyuki) and her boyfriend Shotaro (Nagato Hiroyuki), an eager reporter for the Toyo newspaper. Ueki seems a little downcast at the dockside, and later at home when the phone rings there's something a little troubling about the urgency with which he insists on answering it. "It's been so long since I answered a Japanese phone," he offers by way of sheepish explanation. The following evening he attends a farewell party at his company, but when he has not returned home by the following morning, Keiko enlists Shotaro's help to find out what has happened to her father.

And that's all you really need to get you started here, as what subsequently unfolds is peppered with mysteries and unexpected twists that are far better delivered by the film than by me. By aligning us with Shotaro as he investigates Ueki's disappearance, we know only as much as he does at any one point, but when events take a genuinely unexpected turn (one that plays on our convention-shaped distrust of the authenticity of a telegram), the storytelling canvas expands to include some of those at the root of the mystery.

By keeping us in the dark during the first half, Suzuki invites us to play detective with Shotaro, but in doing so deliberately withholds information that will allow us or him to connect the dots between Ueki's disappearance, an attempted double-suicide, a shipping company and a later murder. Even as the fog begins to clear it remains uncertain how deeply Ueki may (or, perhaps, may once have been) involved, a question first posed by an opening scene in which his luggage is frantically sliced open by an unidentified man who is clearly searching for something of considerable importance to him.

Comparisons have been made elsewhere to a certain celebrated TV series of recent years that I'm not going to name, as doing so effectively functions as a spoiler, and frankly the connection between the two, though intriguing, is a little tenuous. What really grabbed me about The Sleeping Beast Within, however, had less to do with the plot – compelling though it is – than the purposeful economy of Suzuki's direction, Mine Shigeyoshi's scope cinematography (there are some excellent but never showy tracking shots in which the camera glides along with a character in motion) and Suzuki Akira's tightly structured and waste-free editing. And while we may be some way from the genre-busting experimentation of Branded to Kill and Tokyo Drifter, Suzuki still delivers a couple of eye-catching stylistic flourishes, when characters recall a past conversation and the encounter is dramatized while the storytellers remain superimposed over the corner of the screen, a transformation from mid-shot achieved in a single fluid camera movement.

Suzuki maintains the film's brisk pace and sense of filmic economy right up to the end, and bonds us so effectively with Shotaro that even when you can see a twist coming from some distance – I'm thinking specifically of one involving drugged brandy – the timing and triumphant swagger of its delivery still make for immensely satisfying viewing. It all builds to a fiery climax in which moral wrongs are righted in a sacrificial act that gives the ending and unexpectedly downbeat flavour, but which in the context of the drama makes complete sense. It's a solid conclusion to a consistently riveting and energised crime drama that really showcases Suzuki's talent for no-nonsense cinematic storytelling and is probably – by a whisker – my favourite film in this set.

| Smashing the 0-Line / Mikkô zero rain (1960) |

|

In Smashing the 0-Line, Suzuki's immediate follow-up to The Sleeping Beast Within, Nagato Hiroyuki plays an altogether different newspaper reporter in the shape of Katori, an unprincipled hack with none of Shotaro's nobility from The Sleeping Beast Within and a ruthless determination to get the story at any cost. His methods particularly frustrate the more ethical Nishina (Kodaka Yuji), who works for the Nitto newspaper, a direct rival of the Kyokuto paper for which Katori appears to deliver about five scoops a week. The two are actually former school friends who despite having followed very different moral paths are still on superficially friendly terms, which is handy given that Nishina is dating Katori's sister Sumi.

The film's busy first ten minutes are primarily spent establishing that Katori is something of an amoral scumbag who cares little about the fate of people he exploits to land or even engineer a juicy story. Our first real taste of this comes when he visits what we initially (and wrongly) assume is his girlfriend Reiko for sex, after which he dismisses her enquiry about when they will see each other next ("Six years at least, twelve years if unlucky"). As he leaves her apartment, he tosses the key to a waiting detective, who then enters with two colleagues and a newspaper photographer to arrest her for concealing and trafficking drugs. A short while later, Katori agrees to take Nishina with him on another scoop, then skips off without him and at the subsequent police raid simply pushes anyone who bothers him aside in order to continue taking photos. When one arrested suspect makes a run for it and unexpectedly commits suicide (quite how he does this is initially bemusing – we're told that he has bitten his own tongue off but not why this proved so instantly fatal), Katori responds by flipping the body over to get a better photo, despite the fact that the man is Reiko's brother and his former school friend. Katori even ignores his inside man on the story Lee when he is also arrested and pleads for his help, though a short while later he is set free by Katori's police contact, an action witnessed by Nishina that later triggers his own investigation into a smuggling operation and activities of a criminal group known as the 0-Line.

As with The Sleeping Beast Within, the story here is told with remarkable filmmaking economy and an almost dizzying sense of pace. Shots and scenes play only as long as they need to in order to make their point before moving onto the next, which will ensure that an even mildly distracted viewer will quickly find themselves losing track of unfolding events. As an example, take the chance spotting of Lee that kicks off Nishina's investigation. Nishina and Sumi are running happily along a sea wall when Nishina stops dead after spotting Lee in a passing motorboat. Cut to Nishina and Sumi on a small sailing craft as they approach the boat from which Lee and his compatriots are trying to hook wooden brooms that are scattered in the sea around their vessel. They spot Nishina's boat and urgently curtail their activity. Cut to Nishina and Sumi kissing like lovers on a quiet afternoon jaunt. Lee has a filthy snigger and he and his men resume gathering the brooms, one of which is casually grabbed in passing by Nishina. Inside they find smuggled watches sealed in plastic. The whole sequence is covered in 11 shots in the space of just 70 seconds and with only a couple of brief and incidental lines of dialogue, yet it never feels hurried. This is visual storytelling at its leanest and most effective, and if an encounter seems to have no specific relevance to the story, you can guarantee that it will have some significance later – a near collision with a truck carrying gas canisters that is followed by a brief conversation about the dangerous nature of these materials is a blatant Chekhov's Gun moment, there for us to recall later when the material is put to destructive use.

There's a deceiving sense that this busy momentum slows down a little once Katori disappears and Nishina embarks on his plan to get closer to the smuggling operation by setting himself as a stowaway, but that's only because the film becomes focussed solely on Nishina's efforts instead or darting energetically back and forth between locations and people. And it all builds nicely to a series of sometimes violent confrontations and the rather pleasing sense that, despite all they've been through, neither Nishina and Katori are about to change their very individualistic ways. It's a fine companion piece to The Sleeping Beast Within, matching its pace and filmic economy, and in the casting and very different performance of actor Nagato Hiroyuki, explores an altogether different set of journalistic principles.

| Tokyo Knights / Tokyo naito (1961) |

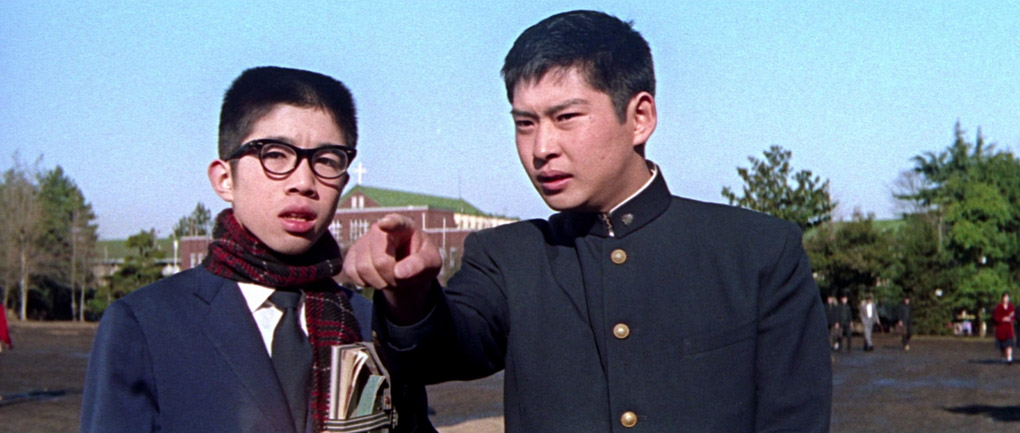

|

There's a song by The Jam titled David Watts, in which Paul Weller laments the fact that he'll never be as cool and popular as the boy of the title, a multi-talented lad who passes every exam, leads the school team to victory and is the object of desire for every girl who lays eyes on him. If Watts has a Japanese equivalent then it's Matsubara Koji in the 1961 Tokyo Knights, the teenage son of a business leader who is unexpectedly made head of the company when his father is killed in a mountaineering accident. Despite his new and weighty responsibilities, Koji wants to and is allowed to continue with his studies, though quite why he thinks he needs to is anybody's guess, as he's already the best at just about everything at his school. This is demonstrated early on in a breathless sequence when he joins the rugby team and wins the game for his side, then abandons them to instantly disarm his opponent on the fencing team, then has similar success at the kendo and boxing clubs before moving on to the music club, where he demonstrates a jazz maestro's skill on the piano that he apparently picked up while studying in America.

For the first impossibly busy 10 minutes or so, Tokyo Knights plays like an energetic high-school comedy, complete with visual gags, a goofy non-Japanese music teacher, a nerdy classmate and a girl who is clearly destined to become the object of Koji's affections. But given that this box set is being sold in part on its crime movie credentials, it's no real surprise that we soon move on to the business end of Koji's new position, and specifically the fractured relationship between the Matsubara and Tokutake syndicates.

Now I will admit here that my poor understanding of how business is conducted in Japan left me a little unsure of how I was supposed to view these two organisations. We can presume that both are simply family run rival business organisations, but there's something about the use of the term ‘syndicate' and specifically the behaviour of the Tokutake clan that had me wondering whether they were completely above board. Maybe this was coloured a little by my own past experience in Japan, where I was introduced by a close friend to people she grew up with and invited to attend their annual spring get-together. Here, I met representatives of a number of local companies who were all part of a business syndicate that appeared to protect each other's interests, sometimes at the expense of those who had not yet been invited to join this group. The imposing head of this syndicate treated me well, but every time I met him I had the uneasy feeling that I was shaking hands with a man who was as much a gang leader as a business executive. I had exactly the same feeling about the head of the Tokutake clan, a suspicion later confirmed when his own daughter, Yuriko, openly admits that her father is a gangster. And as a romance develops between the teenage offspring of these opposing clans, it's hard not to suspect a small Shakespearian influence, one that casts the Matsubara and Tokutake families as the Montagues and Capulets.

As Koji begins taking an interest in business matters that have previously been handled by his father's second-in-command, Mishima, he also starts looking into the circumstances of his dad's death, which he regards as suspicious. What we learn before he does is that Mishima is in league with Tokutake, who plans to dissolve the Matsubara clan and absorb all of its assets, a plan that has Koji's mother's approval. What unfolds is an oddball blend of crime drama and daffy comedy, laced with occasional dashes of surrealistic peculiarity. This aspect peaks when a group of the Tokutake goons take Koji to a nightclub with the aim of getting him drunk, a sequence whose billowing red curtain backdrops and colourfully lit singer look almost like a trial-run for Dorothy Vallens' performance of the title song from Blue Velvet. Elsewhere, Koji goes on a cufflink-stealing spree (he's following up a clue to his father's death) wearing a cloak and that scary demon mask from Onibaba, and as he darts between rooftop obstacles and leaps on the Tokutake boys, seemingly from nowhere, it briefly struck me that I was almost watching a template for the night-time activities of the protagonist from V for Vendetta. There's even a sequence, one involving a fight we never see in which the seemingly overwhelmed Koji floors a group of bullies, that in some ways anticipates the before/after editing gags of Kitano Takeshi. Maybe, just maybe, I'm reading too much into this.

Either way, Tokyo Knights is a peculiar concoction, a head-on collision of seemingly incompatible genres – there are even a couple of diegetic musical numbers and an on-stage dance performance (yep, our Koji is brilliant at that too) – that shifts between the serious, the comical, the silly and the ever so slightly surreal with a complete disregard for tonal continuity. For many – Asian cinema expert Tony Rayns included – this will likely be a bit too much to swallow, but I thought it was great fun. Sure, there are few real surprises in the plot, but there are a few in the execution, which really does keep you guessing about where it will go next, and nothing in the energised opening 20 minutes prepares you for the considerably more serious tone of the climax. All of which does, in its own daffy way, make for curiously cross-cultured and oddly entertaining viewing.

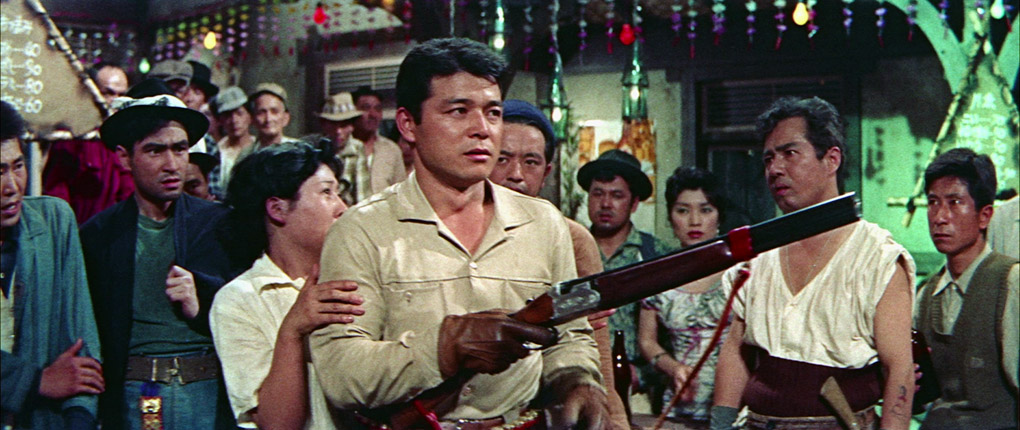

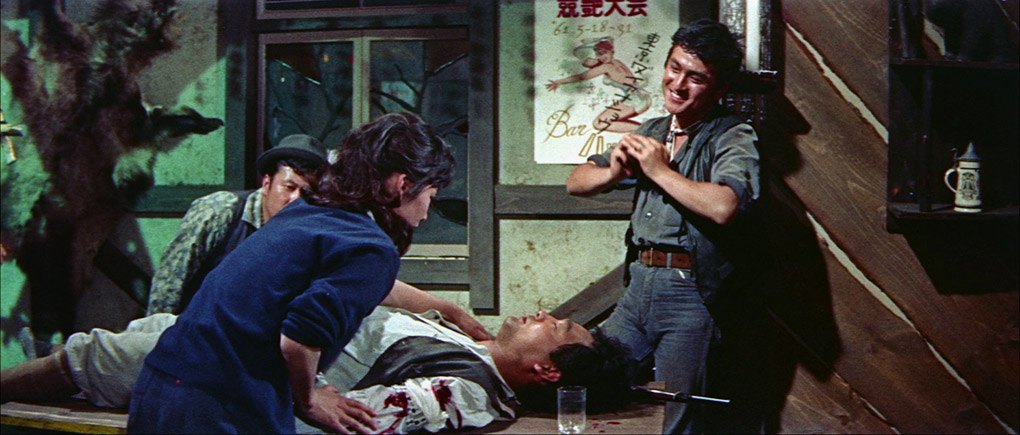

| Man with a Shotgun (1961) |

|

I'd read nothing about this one before sitting down to watch it, but despite being set in a mountain region of Japan in what at the time of filming would be classed as present day, just five minutes in I knew without question that I was watching a western. A Japanese western, yes, but one drawn explicitly from the sort of American B-movie genre works the Nikkatsu studio had been distributing in Japan for some years at this point. Even more so than The Sleeping Beast Within and Smashing the 0-Line before it, Man with a Shotgun cheerfully wears its American influence on its sleeve.

The shotgun-wielding fellow of the exploitation-friendly title is Ryoji (Nitani Hideaki, who was later to have a substantial role in Tokyo Drifter), who rolls up at an isolated lumber camp after successfully outmanoeuvring a band of its workers, who then claim that they were just testing Ryoji's toughness. He is quickly invited to stay by the owner, Nishioka, and is further tested by three criminals who have been acting as Nishioka's bodyguards in exchange for being allowed to hide out at the camp. That he's arrived there by chance is cast into doubt when he discovers that a necklace that is clearly of some personal importance to him has been traded in for drinks at the camp's bar by an unknown party.

Local law and order is precariously kept by the rifle-wielding Okumura, a former charcoal maker who's taken up the post of sheriff in order to get his hands on a gun and avenge the rape and murder of his wife. It quickly becomes clear that he's not up to the job, and when he's injured in an ambush, Ryoji puts himself forward as an ideal replacement, but finds himself at odds with the hot-headed Masa, who's convinced that he is more suited for the role.

A whole string of American western conventions (or possibly clichés) are paraded at an early stage here, including the mysterious stranger who may or may not be seeking revenge for a past crime against himself or a loved one, a trio of outlaws who are destined from the off to go up against Ryoji, and a black-dressed rival whose skills are equal to Ryoji's own. Just in case you somehow don't make the connection, Suzuki liberally peppers the screen with genre iconography: the lead characters dress like cowboys and get into standoff duels and fist fights; the bar in which they socialise is kitted out like a classic western saloon (complete with ornamental ‘batwing' doors and spontaneous bar brawls); and the lumber mill and surrounding buildings have the air and geographical isolation of a frontier town. And despite an occasional cameo by a motorised vehicle, the whole thing feels as if it could be taking place back in the 1880s rather than the early 1960s.

It's all harmless and slightly bizarre fun – there's even a song! – but as a content-light and sometimes ramshackle knock-off of American westerns of the 1950s, it did leave me pining for the films it so cheerfully and brazenly takes influence from. By the climactic scenes, the tight editing that characterises the other films in this set also begins to feel a little more raggedy, creating the sense that the filmmakers ran out of time and had to complete some sequences with whatever they had to hand. But this is still energetic and curious enough to be worthy of your time, one whose late-film twist I genuinely didn't see coming, and of all the films in this set, this is the one that most clearly deserves to be labelled a "borderless action" movie.

There is some variance in the image quality here, but all five films have clearly undergone restoration and are presented in 1080p HD on the Blu-rays in this set.

The oldest film here, Eight Hours of Terror, is the only one framed 1.33:1, which is clearly the original aspect ratio. The image is generally sharp and with a good level of detail, and while the black levels are not quite as beefy as on other films in this set, the contrast range is generous enough to avoid losing any crucial picture detail to darker areas. The print is also very clean and free of any major damage.

The source material used for the 2.35:1 transfer of The Sleeping Beast Within was clearly weaker than that used for Eight Hours of Terror, resulting in a picture whose detail is on the soft side and never looks pin sharp, at least on a large screen. The contrast is punchy, however, with strong black levels and bright highlights, which occasionally threaten to burn out but never do. Once again, the print is very clean and displays no serious damage, though a few small scratches are occasionally visible.

The 2.35:1 transfer of Smashing the 0-Line is noticeably sharper than The Sleeping Beast Within, and also boasts a more generous contrast range. The black levels are solid, but just occasionally the detail is burned out on highlights, such as white shirts or blouses in sunshine, though this could well be how they were originally exposed. Again, the image is clean and free of damage.

Tokyo Knights is also 2.35:1 and in colour and boasts a vibrant colour palette, something particularly evident in the nightclub scenes. The contrast is nicely pitched, and the sharpness and detail are both very impressive. Once again, the picture is largely clean, but there is some remaining dust visible around some of the reel changes.

The 2.35:1 colour transfer of The Man with a Shotgun may not be reference quality, but the sharpness and detail are both very good. The colour has a slightly unnatural earthy hue that is typical of films of the period, though brighter colours are often lively. The print is largely clean, though the odd dust spot does remain, and once again they tend to get briefly busier during some of the reel changes. More noticeable are the splice marks that make a brief appearance at the very top of frame on many of the edits. They're not too intrusive and you get used to them. The image is stable, but a couple of times is hit by a brief bit of judder.

All five films have Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtracks in the original Japanese, and optional English subtitles that are activated by default. All five soundtracks have the expected restrictions on dynamic range and treble bias to the dialogue and music, but all five are also clear and free of serious damage. There is a faint hum detectable in quieter scenes on almost all of the films, but it's never distracting and is usually lost beneath the recorded sounds. There's a tad more crackle and fluff on The Sleeping Beast Within, as well as the occasional pop on reel changes. Otherwise, all are in decent shape.

Jasper Sharp Commentary on Smashing the 0-Line

Writer and Midnight Eye co-founder Jasper Sharp delivers a commentary that is only occasionally screen specific, but which imparts a wealth of information on Suzuki, his movies and this film's key cast members. It's consistently interesting stuff, engagingly delivered, and unless you've written your own book on Japanese cinema there's a good chance you'll learn a lot here. I certainly did.

Tony Rayns on the Crime and Action Movies (49:21)

Asian cinema expert Tony Rayns provides an enthralling overview of all five films in this set. He credits Eight Hours of Terror with having a more interesting and imaginative script than other Nikkatsu films of the period, talks about its characters and the Nikkatsu contract players, praises its handling of the multi-stranded storyline and its submerged politics, making interesting comparisons to the recent Train to Busan. The Sleeping Beast Within and Smashing the 0-Line are discussed as companion pieces, notably their use of actor Nagato Hiroyuki, their treatment of a drug trade that is largely alien to Japan, and their lack of a specifically Japanese identity. He's not so complimentary about Tokyo Knights, which he regards as the only really weak entry here, but is more enthusiastic for Man with a Shotgun, acknowledging its absurdity but making a case for it as a the perfect "borderless action" film. There's plenty more, all of it of considerable interest.

The Sleeping Beast Within Trailer (3:25)

A typically lively, if structurally ramshackle trailer that alternates between dialogue scenes and aurally muted action footage, all set to a blaring jazz tune. As ever, the captions that flash up on screen are rather entertaining, at least if their subtitle translations are anything to go by, with Shotaro rather unfairly condemned as a man who "causes suffering with his shallow writing," and the turmoil of crime colourfully described "Madness on the edge of the abyss of life."

Smashing the 0-Line Trailer (2:54)

"Angry roars…desperate screams…deep resentment" are some of the delights promised by the captions of this energetic and jazz-driven trailer. They also assure us that "in the swirling vortex of the media is a man too callous for his youthfulness" and say things like, "squirming in the dark abyss, these bastards for whom there is no tomorrow."

The Man with a Shotgun Trailer (4:16)

Lots of fighting and shooting and a couple of serious spoilers in this busy if unevenly paced trailer (the action stops at one point for a long arrest sequence captured in a single wide shot). But it has "mutiny and pressure" and is "a great spectacle" with "a splendid cast."

Tokyo Knights Trailer (3:51)

Kicking off with the film's most surrealistic sequence, this trailer, which bounces along to mix of urgent jazz and the sort of tune I'd expect to find in a trailer for a Carry-On film, is not the most seductive sell in the world, and describing it as "a masterpiece from director Suzuki Seijun" is really pushing it.

There are Stills Galleries for all five films spread over the two discs, running for 20 to 26 slides per title.

The release version also includes a 60-page illustrated collector's book featuring new writing by Jasper Sharp, but this was not available for review. On the basis of how informative Sharp's commentary on Smashing the 0-Line is, however, I'm willing to bet it's a terrific read.

I've come to Arrow's Suzuki Seijun box sets arse about face, as my late father used to say, getting the second set first, not that this really matters with sets containing five stand-alone films. All were made several years before the films that so enraged the Nikkatsu bosses, and all showcase Suzuki's considerable talent for pacey, economical film storytelling. I'll admit to being less enthralled than Tony Rayns with The Man with a Shotgun and enjoyed the silliness of Tokyo Knights considerably more than he did and have nothing but praise for the other three films in this set. For anyone with an interest in the films of Suzuki Seijun, the concept of "borderless action" movies or Japanese crime cinema of the late 50s and early 60s, this is a must-have. If that includes you and you don't already have this set, be aware that it's a Limited Edition and thus will not be available indefinitely. I'm now off to get my hands on the first box set while I still can and am looking enthusiastically forward to Arrow's upcoming Blu-ray release of Suzuki's brilliantly titled Detective Bureau 2-3 Go to Hell Bastards!

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for all Japanese names in this review. Pleasingly, both Jasper Sharp and Tony Rayns also respectfully observe this convention in the special features.

|