|

A married man and his lover are found dead in a hotel room, an apparent double suicide instigated by the woman out of guilt for the hurt their relationship would inflict on the man's family. At least that's what the crime scene officers conclude. As it happens, the woman is actually a call girl, and the cops soon discover that the man is Police Detective Takeshita Koichi. What could this mean?

A few days later, white hatted, black coated, cigarette smoking Mizuno Jôji – "Call me Jô for short" – starts a fight in the street, assaults a man in a pachinko parlour, and roughs up a waiter at the sort of club that serves attractive girls with its drinks. The establishment is run by Soichi Ozawa (Keneko Nobuo), the superior of one of the men that Jô beat up earlier, who is promptly brought in to identify his assailant. The unarmed Jô is then escorted into a soundproofed office that has a goldfish bowl view of the club and even the room above. Seemingly unconcerned by the threats made against him, he disarms one of the goons and pistol-whips him senseless with his own gun. Soichi responds by hiring Jô on the spot and for a sizeable fee. He then informs him that he will introduce him to the boss. "You aren't boss?" asks Jô with a curious look of disappointment.

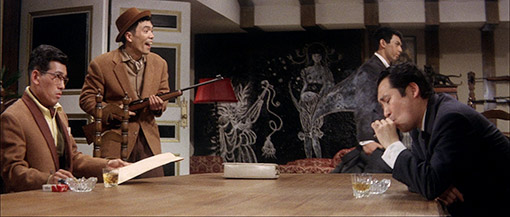

The real boss is Nomoto (Kobayashi Shoji) and he's an absolute peach, a sort of Japanese Ernst Stravro Blofeld who carries, coddles and kisses a large and fluffy white cat and who can pin a man's sleeve to the wall with a throwing knife in the blink of an eye. It's a skill that he demonstrates the moment Jô walks in the door. Quite why he does this is anybody's guess. When Jô then outwits cheerful mobster Minami (Esumi Hideaki) with a second gun hidden in his hat, Minami is delighted and forms an instant attachment to this surly newcomer. The friendship is sealed when Mizuno makes him a present of an assassin's rifle, after first pissing him off by refusing to let him touch what he calls "the tools of my trade". The plot thickens.

At the headquarters of the rival Sanko gang led by Onodera Shinsuke (Shin Kinzô, who here looks a bit like a Japanese Lyle Lovett), word comes in that someone is trying to shake down one of firms under their protection. Want to guess who? The would-be victim of this attempted extortion is having none of it, however, at least until Jô sets his hair on fire using a can of hairspray and a lighter as an improvised blowtorch. When the Sanko men show up in force, the seriously outnumbered Jô is doubtless rather glad that he gave that gun to Minami. Cheered by the result of their activity, Minami pledges not to work without Jô in the future. He even wants to hang out with him for the rest of the day, but Jô has a memorial service to attend. "An old friend of mine," he assures Minami.

This brings us back to that opening double suicide, and given that this memorial service is overrun with cops, you can't help wondering what it is about the late Takeshita-san that is so important to this hard-nosed and mysterious yakuza wannabe. "A long time ago, your husband was very kind to me," he tells the man's widow, but the suspicion is that there's more to it than that. Indeed, pretty soon he's making discrete enquiries into the circumstances surrounding Takeshita's death and even strong-arming Nomoto's gay, razor-wielding brother Hideo (Kawaji Tamio) for information. When the still sore Sanko gang attempt to grab him, Jô turns the tables on them and makes Onodera an offer he can't refuse, demanding and securing a sizeable fee to feed him information about the Nomoto gang. Just what, one wonders, is he up to?

Just about everyone with an interest in 60s Japanese crime cinema should know the name of Suzuki Seijun (I know the names are usually the other way round, but we tend to go with the Japanese convention of surname first here). A contract director for Nikkatsu, he specialised in no-nonsense, crime themed B-movies, but was also the man behind Tokyo Drifter [Tôkyô nagaremono], a wild and wonderful twist on the standard yakuza drama that was gloriously described on the sleeve notes of its first Criterion DVD release as a "free-jazz gangster film." It really is the stuff of great cult cinema, but did not sit so well with Nikkatsu bigwig Hori Kyûsaku, who was by then demanding that Suzuki tone down the surrealistic elements and convention breaking stylistics that were creeping into his films. He didn't, bless him. Instead he made the 1967 Branded to Kill, a masterpiece of offbeat gangster cinema that was championed by western critics and remains a personal favourite of the likes of Wong Kar-wai, John Woo, Park Chan-wook, Kitano Takeshi, Jim Jarmush (whose Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai borrowed freely from it) and, of course, Quentin Tarantino. Hori was considerably less impressed, describing it as "incomprehensible" and a lot worse, and using his hatred of the film to give Suzuki the boot. But the vindictive bugger didn't leave it at that. Hori subsequently withdrew every one of Suzuki's films from distribution and refused to let any of them be screened. Suzuki responded by suing the studio for wrongful dismissal, which resulted in a two-and-a-half year court case that attracted widespread public and critical support for the director. Suzuki ultimately won but was awarded only fraction of the claimed damages and was blacklisted by all the major Japanese studios for the next ten years. Lovely business, filmmaking.

Youth of the Beast [Yajū no seishun], is generally regarded as Suzuki's breakthrough movie, the one in which he first started to develop the style that would gain him a worldwide following but ultimately lose him his job. Adapted by Ikeda Ichirô and Yamazaki Tadaaki from a novel by Ohyabu Haruhiko, it's as densely plotted as any of Suzuki's previous yakuza films (or at least the ones I've been able to see), and has enough twists in the second half to keep even the most alert of viewers on their toes. It also proves a splendid showcase for the talents of leading man Shishido Jô, who, like Suzuki, is best known for his yakuza movies and is most internationally famous for his lead role in the very film that brought Suzuki's career to a halt. Oh, the irony. And he's terrific here, a calculating loner who exudes don't-give-a-crap cool and has a winning way of turning the tables on his opponents. There's more than a whiff of Yojimbo about the manner in which he sells himself to both mobs and them plays them against each other, and there's even a nod to Sam Fuller's Tokyo-set House of Bamboo in the basic set-up and the motivation behind his actions.

Fuller's Tokyo-shot film is not the only American crime movie exerting an influence here. As Tony Rayns points out in his accompanying video essay, the liberal use of firearms is actually incongruous to the location and period, and seems to be more about importing a particular aspect of American crime movie chic. But when it's put to such good use, who's complaining? Repeatedly Suzuki has his characters employ firearms to creatively surprise and/or outwit their opponents, my favourite being Jô's dive through a Sanko gang car to grab a shotgun that he then wedges under the head goon's chin. "From this range," he calmly informs the man, "it'd be hard not to blow your face off," conveniently omitting to mention that the gun's firing pin is actually knackered.

The odd over-the-top moment is there, notably the heroin addicted call girl (Kazuki Minako) whose screaming desperation for a hit sees her quite literally tear up the scenery (the subjective view of her tormentor that follows is rather nifty, however, and once she gets her drugs she's rather impressive). But for the most part Youth of the Beast is a stormingly good and frequently inventive yakuza thriller; fast-paced, appropriately violent (at one point Jô is tortured by having a knife poked under his fingernail) and littered with neatly-timed and often unexpected twists. The supporting characters are all distinctively cast and given interesting traits to make them individually memorable, though my favourite has to be the perennially cheerful and wily Minima – it's only through his developing friendship with Jô that we get to glimpse the latter's suppressed humanity, and his sudden and instinct-driven shooting of a woman he has just fallen for delivers what for me was the biggest shock in the film. It's also rather refreshing to encounter a movie made back in 1963 that features a gay gangster who, while just a little effete is his manner, is not judged by others for his preferences and is clearly every bit as loyal and lethal as his more heterosexually inclined compadres.

Ooo, hasn't this scrubbed up well, and I mean really well. What makes it all the more surprising is that there are some A-movie Japanese features from the period that don't look anywhere near as good as this on Blu-ray or DVD. The 2.35:1 image is breathtakingly clean, the colours lively when they need to be, the contrast nicely balanced, even at night, and the level of detail is... well, put it this way, you're never in doubt that you're watching a Blu-ray. A fine level of natural film grain is visible, and no obvious signs of edge enhancement are present. Very nice.

The linear PCM mono Japanese language track is as treble-biased as expected, but is otherwise clear, free of damage and not blighted by any background hums or hisses. Clear optional English subtitles are provided.

Tony Rayns on Youth of the Beast (26:03)

The venerable Mr. Rayns, Masters of Cinema's first go-to for opinions on Japanese films of any period, delivers an engrossing and almost unbroken (there are film clips to hide the edits) dissertation on director Suzuki Seijun and Youth of the Beast in particular. Interesting to hear that Suzuki once claimed in front of an audience (when being interviewed by Rayns) that he was a better director than Imamura Shohei, a compatriot at Nikkatsu whom he felt received preferential treatment. The detail on what makes Youth of the Beast different to Suzuki's previous films is useful, and Rayns' analysis of what makes this film so interesting nails a few things that I'd only subconsciously picked up on, notably the lack of scene transitions and expositional dialogue. I was also amused to hear the post-plastic surgery Shishido Jô described by Rayns as "interestingly ugly." Sure he'd love that. An enthralling extra feature, though appears to have been shot on a DSLR, whose narrow depth of field is not too forgiving when Mr. Rayns occasionally leans forward. Ah, who cares? Listen to the man!

Trailer (4:16)

"Those bastards messed up my life!" the subtitled opening text proclaims as Okumura Hajime's jazzy score blares away in the background. It also promises VIOLENCE, DRUGS, A DEADLY DEAL and EVERY KIND OF VICE. Hang on a minute. Every kind? A number of equally attention-grabbing lines follow, including "Leave those worms to me!" and "Senseless cruelty vividly portrayed," which is splashed over a sequence that includes a close-up of the knife-under-the-fingernail torture that's not in the film, at least the version presented here. A pretty damned good sell overall.

Booklet

The centrepiece here is a detailed essay on Suzuki's career and the importance of Youth of the Beast in the director's oeuvre by Frederick Veith, critic and scholar of Japanese film, and Phil Kaffen, who teaches courses on film, literature, philosophy, and mass culture in Japan at New York University. They usefully provide some cinematic context for the film's production and release, do a little myth-busting on the circumstances surrounding Suzuki's dismissal from Nikkatsu, and explore the film's socio-political relevance. Trust me, it's a lot more interesting than I make that sound. There are also some rather nice stills, main credits for the film (though I could have done with a more detailed cast list) and the usual notes on viewing.

A hard-boiled, fast paced and busily plotted yakuza thriller that lays the early groundwork of the stylistic evolution that Suzuki's cinema would undertake over the course of next four years. With so few of Suzuki's films currently available on Blu-ray, this release on Eureka's Masters of Cinema label is to be cherished, particularly given the quality of the transfer and (limited but well targeted) extra features. Definitely recommended.

|