|

John Ford is one of a handful of filmmakers whose name is so widely known and whose work is so revered that there’s little I could say about him here that isn’t already common knowledge. It’s because of this that I kept the introduction of my review of Indicator’s John Ford at Columbia 1935-1958 box set so brief, and I see no reason to do otherwise here. Where the Indicator collection focussed on four of Ford’s lesser-discussed sound era films, this two-movie set from Eureka is comprised of two films from the earliest days of his feature career, when he was regularly credited as Jack Ford rather than John. Both films are westerns, a genre with which he would later become synonymous, and both are obviously silent with added musical scores, having been made a good decade before the arrival of sound. More crucially, both are from a period in Ford’s filmography that has been largely consigned to history, with many of the films he made during this prolific time – he directed over 40 features between 1917 and 1922 – now considered lost. Both Straight Shooting and Hell Bent were also once believed to have suffered this fate until prints for both were discovered in the Czechoslovak Film Archive and subsequently restored by NBC Universal. Both are important works in that respect, and if you go in expecting the cinematically primitive and hesitant first steps of a fledgling director then you’re in for a surprise, as Ford, despite his young age, is one filmmaker who absolutely hit the ground running.

I seem to remember a song in Oklahoma! that helpfully suggested that the farmer and the cowman should be friends, even though they rarely are in westerns. In the 1917 Straight Shooting, the farmers are new settlers in the area around the town of Diabolo and deeply unpopular with cattlemen whose access to every square inch of vast open plain is somehow disrupted by these varmints having the nerve to build the odd house there. Actually, there’s slightly more to it than that, as the song handily reminds us – “They came out west and built a lot of fences,” “and built them right across our cattle ranges.” Enter cattlemen leader, ‘Thunder’ Flint (Duke Lee), who has decided to wage war on the settlers and ultimately drive them out of the district.

A prime target of Flint’s wrath is the kindly old ‘Sweetwater’ Sims (George Berrell), whose unconquerable spirit has seen him become the settlers’ leader. Sweetwater has set up home with his daughter Joan (Molly Malone) and son Ted (Ted Brooks). Ted is the apple of his father’s eye and Joan has become the object of affection for young Danny Morgan (Hoot Gibson), a puncher on Flint’s ranch who refuses to take part in any of his employer’s more dastardly schemes. At least that’s what his introductory title card claims, but when Flint fences off the area’s only source of fresh water and sends a letter warning the Sims to stay away or else, it’s Danny who is given the job of delivering it.

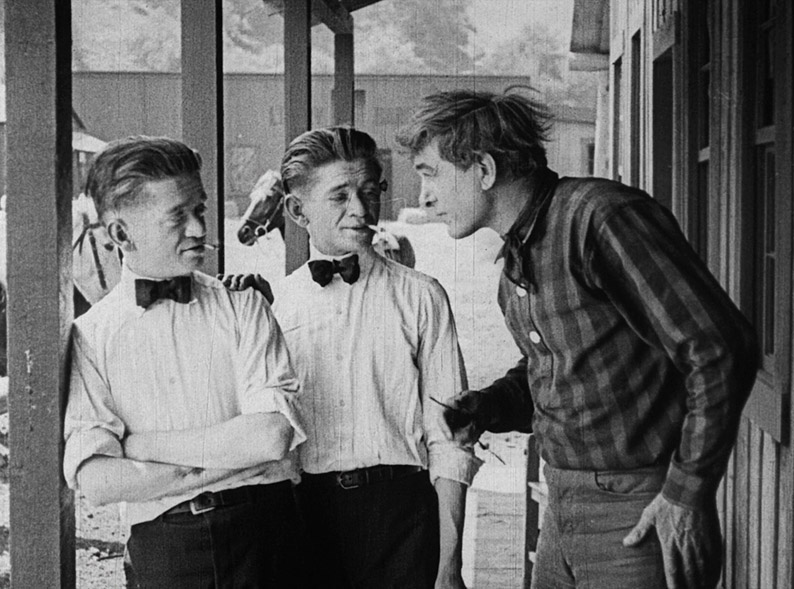

To aid him in his quest to eject the settlers, Flint then tasks Danny with the job of finding and hiring a notorious gunslinger named Cheyenne Harry (Harry Carey), who currently has a substantial price on his head. When Danny locates him, he’s in a drunken stupor, but is able to rouse himself enough to hear the boy out and accept the job. When Harry reaches Diabolo, however, he discovers that Flint has hired a second gunman named Placer Fremont (Vester Pegg). After slowly sizing each other up, the two get drunk and become pals, but when Placer takes unilateral action that results in tragedy for the Sims family, Harry is so moved by their grief that he effectively tells Flint to stuff his job, which prompts Flint to add him to Placer’s hit list.

The press notes for this Blu-ray release describe Straight Shooting as a landmark film and with good reason, given that it was John Ford’s first feature, directed when he was just 23 years of age, and almost nothing about this film betrays that fact. Take the shot that introduces Flint, an ambitiously organised and strikingly composed image (props to cinematographer George Scott here) that almost has the look of a painted portrait. Less classical but more inventively comical is the introduction of Cheyenne Harry, which comes immediately after his own wanted poster has been nailed to a hollowed-out tree, from which Harry then unexpectedly pops like an inquisitive squirrel. Ford’s purposeful and emotive use of landscape wides would become a signature feature of his westerns in the years to come, as would the male bonding that sees initial rivals Harry and Placer become friends, only for them to later morally diverge. His grasp of the power of the facial close-up is also clearly evident here, as is his understanding of how pace can be built in the editing and how to use framing to add secondary meaning to an image. A fine example comes when Joan is shown standing longingly by the door of the house, first in moving close-up, then viewed from behind the emotionally conflicted Harry’s head, an image that communicates so much without a word of (captioned) dialogue. More experimental is a blurred image of the Sims family in mourning seen from Harry’s viewpoint, with what initially looks like a shot that was too damaged to repair is revealed to have been deliberate when Harry then wipes away the tears that were previously muddying his vision. Ford devotees will also likely delight at a shot of Danny riding up to the Sims house and framed by the dark of the front door of the house, a moment that would be later repeated in Ford’s masterful The Searchers.

Given that these early westerns were instrumental in establishing the later codes and conventions of the genre, it’s hardly surprising that the film in some ways plays to expectations, but being made so early in the genre’s evolution it’s also not bound by unspoken rules that have yet to be established. An audience of the day could have been forgiven for believing, for example, that Cheyenne Harry was going to be the villain of the piece, despite his cheeky introduction and his comical bonding with Placer. Yet even when he elects to side with Sims family and becomes the nominal hero, things do not play out as you might predict. The nature of his interest in Joan, for example, initially comes across as a longing for a more settled life, as he observes the tenderness with which she attends to the injured Danny. Yet when Joan starts to take a more active interest in Harry, this creates a moral quandary that is never comfortably settled, as unlike goofy hayseed Charlie McCorry in The Searchers, Danny is a genuinely nice guy who really cares for Joan and is thus not in any way deserving of being dumped in favour of this newcomer. Adding to the ambiguity here is a nagging sense that the film has a second and originally unintended ending, a suspicion given weight by the noticeable drop in image quality in the final scene, although given the film’s age and the single source used for the restoration, I’m aware this doesn’t exactly constitute hard evidence.

That Harry and Placer will face off in a gunfight also has a degree of inevitability to it, and at first it looks very much as if they’re going to do so in what would become one of the genre’s most famous tropes. As they slowly approach each other on the Diabolo main street, the citizens – including the corrupt and dandily dressed sheriff – scatter and hide, yet what unfolds has more in common with the strategic manoeuvring of High Noon than the face-off shootouts of western legend. It’s also easy to forget that Harry is not a good-hearted innocent but was hired by Flint because of his fearsome reputation as a killer. It’s also worth noting that the gang whose help Harry secures to aid the settlers – one led by the splendidly named Black-Eyed Pete (Milton Brown) and that Harry has clearly ridden with in the past – are outlaws who make their living by stealing from others, a comical reminder of which we’re given in the aftermath of the climactic battle. In that respect, Harry is the epitome of what has been described as the Noble Outlaw, a figure that would make repeated appearances throughout the course of Ford’s western oeuvre.

Straight Shooting is a genuinely remarkable first feature for so young a director, one that may follow an already laid-out pattern for the genre but whose handling and focus on character, coupled with its refusal to paint its lead character in idealistic colours, gives it a maturity that feels genuinely ahead of its time. The performances are more nuanced than you might expect for a silent film of the period, with Carey a most enigmatic lead, Molly Malone a winning blend of innocence and quiet alure but able to leap into action when the situation requires, and some nicely naturalistic work by Ted Brooks and Hoot Gibson as Ted and Danny. Only in the all-action climax does Ford’s relative newcomer status momentarily show, as groups of similarly dressed cowboys gallop at high speed in breezily edited wide shots that occasionally had me uncertain who I was looking at and exactly where they were heading. It’s a small and frankly insignificant gripe in an otherwise belter of a debut feature, and one that leaves you aching for the many subsequent collaborations between Ford and Carey that we will likely now never get to see.

Hell Bent gets off to an intriguing start, one that could be seen a precursor to one of the smartest photographic tricks pulled off by Greg Toland and Orson Welles in the later Citizen Kane. It opens on author Fred Worth, who has been asked by his publisher if he could make the lead character of his next novel a more ordinary and imperfect man instead of the unrealistically virtuous heroes of which the public is tiring. Pondering on this, the author walks over to Frederic Remington’s painting, A Misdeal, which the camera moves in on and which then dissolves to a live-action recreation of the very same scene. It may not be seamless, but it’s still an ambitious and impressive attention-grabber for a western made over a century ago.

The scene depicted in this image is the aftermath of a saloon card game in which accusations of cheating have provoked a shoot-out that has left men dead and injured, while the man who instigated the feud has fled and is heading for the safety of the county line. The gambler in question is none other than our old friend, Cheyenne Harry, and once safely beyond the reach of his pursuers he stops to get his breath back and dispose of the cards he has secreted in seemingly every pocket in his clothing. It’s a short sequence that had me laughing out loud, as much for the half-sloshed weariness of Carey’s expression as the number of hiding places he has for winning cards. This was the first inkling I had that Hell Bent would not be taking its subject matter quite as seriously as the earlier film.

Harry then heads for Deadwood, but before he gets there we’re introduced to a few of the key characters in the story to follow. First up is feared bandit, Beau Ross (Joseph Harris), whom we first encounter when he and his gang cover their faces to hide their identities and hold up what they mistakenly believe is a coach carrying a Wells Fargo strongbox. Instead of shrinking with fear, the driver responds with a casual, “Hi, Ross!” and I’m laughing my head off all over again. Ross immediately denies that he’s Ross, which makes only a superficial impression on the unintimidated driver, who replies with a friendly wave, “I was mistaken.” Up next is pretty Bess Thurston (Neva Gerber), whose brother Dave (Vester Pegg)* is employed at the local Wells Fargo office. Their mother has written asking for money for medical bills (ah, the American healthcare system strikes again), something Bess believes they should act upon immediately but which Dave dismisses as impossible in their current financial situation.

The local saloon is a lively spot, and it’s into here that Harry rides looking for a room, and when I say rides, I meant it literally, horse and all. Here he is informed by the flustered manager that the only space is in a bed he’d have to share with a man named Cimmaron Bill (Duke Lee), and he wants no bed-mates. Not to be dissuaded, Harry rides up the stairs and into Bill’s room, where his horse starts eating the hay in Bill’s mattress and the two men get into a tit-for-tat battle that results in each of them jumping through the window at gunpoint. They finally unite over a chorus of Sweet Genevieve, then agree to share the bed and wake the next morning the very best of pals. Read into that what you will.

That Harry and Bess will catch each other’s eye and that Harry will put his roguish ways behind him and reveal the noble man that dwells within are both inevitable in a western made during the foundation years of the genre. But in keeping with the brief provided to Fred Worth in the opening scene, Harry is once again not your typical early western hero, and just a couple of decades later would likely would have landed Ford and his collaborators in all sorts of trouble with the Production Code censors. From what we see of the aftermath of the card game from which he fled, it looks very much like he killed three of his fellow gamblers and injured a fourth, actions that would not be allowed to go unpunished once William Hays was calling the censorial shots. Even when Harry gets to play the hero by rescuing Bess from a rambunctious crowd, he then blows his chances first by manhandling her and then drunkenly attempting to force himself on her. In what feels genuinely more progressive than a good many subsequent films, Bess reacts with clear discomfort at being grasped, then slaps Harry’s face and angrily admonishes him when he suddenly grabs and kisses her. Good on you, girl!

Going into the film with little knowledge of what to expect, what really caught me out was how genuinely funny so much of the first half is. Carey is a natural here, seemingly half-drunk even when we haven’t seen him hitting the bottle, and even more comical when legitimately sloshed, particularly in the company of his new bestie, Bill. As I noted above, much of this prompted loud laughs on my part, and I’ve not even mentioned the alcoholic Harry’s look of suspicious bemusement when Bess presents him with a cup of tea or his cack-handed attempt to pick it up and drink it. At one point stop he is stopped in his tracks by twin brothers who look as if they’ve travelled back in time from an early and previously unseen David Lynch short, and despite being a silent film, Ford finds comedy mileage in the singing of a song and the effect it has on any anyone within earshot. He even uses the inter-titles to include a wordplay gag when the saloon owner asks, “Here’s your bill, Bill. Think you might pay for once?”

The comedy takes a back seat in the more story-driven second half, as the newly unemployed Dave falls in with Ross and Harry decides to intervene and stop a robbery, then has to head off to rescue to the kidnapped Bess from Ross and his gang. It’s a structurally sound approach that uses the first half to bond us with the characters that we’ll thus care about when they’re launched into action in the second. Even here there are a few surprises, with the inevitable showdown between Harry and Ross not playing out as expected and leading to a fight for survival in which both men end up on the same side. It’s also pleasing, particularly for such an early western, to see Bill going out in search of his friend in the company of a Native American and the two are never shown as anything but equals.

Although one of Ford’s earliest westerns and made when he was still just 24 years of age, the direction is one of the stars of the show, from the sometimes superbly arranged and framed exterior wides (in one extraordinary wide shot, a wagon is torn apart as it passes the camera, which tilts down to follow the debris and comes to rest on a lower section of the road just as the horses re-enter frame and the wagon completes its disintegration) to the emotive use of facial close-ups and the contribution made by the editing to the very visual approach to storytelling. It may not be the landmark film that Straight Shooting is by default, but it’s still a highly accomplished western whose rollicking first half is also a barrel of fun.

Both films are framed 1.33:1 and have been restored by NBC Universal from prints discovered in the Czechoslovak Film Archive. Neither is in perfect shape, with a great many narrow scratches and other small instances of damage remaining, something those responsible for the restoration have done their best to minimise. Such wear and tear still remains very visible, but I quickly got used to it and never found it to be a distraction. More significant are the number of missing frames, which do result in some sudden small relocation of characters and the occasional larger time jump, which can see a person who is lying on the floor one second be standing and talking to someone the next. Frankly, given the fact that these were once lost films, this is easy to live with and only once in Straight Shooting does it result in a little confusion, though even here it’s easy enough to guess what has happened in the missing footage.

Pictorially, Straight Shooting fares a little better than Hell Bent, having slightly punchier but still decently balanced contrast and more crisply defined detail, and there is some minor burn out in the brighter areas in Hell Bent. Wider shots in particular feel a little more robust on the earlier film, although both films are at their best on facial close-ups. Neither is as sharp as the best silent restorations, but this is hardly surprising when you consider that neither was rebuilt from the original negatives, and the work required to minimise some of the scratches may also have had a small impact here. Both films are stable in frame, with no jitter or jumps in the picture even when frames are missing. Given that both films have effectively been brought back from the dead, I was impressed with how good they look here. It’s also worth noting that as the inter-titles on the sources prints were in Czech, they have been recreated in English in the style of the original captions on both features by the restoration team.

Both films feature new scores presented in clear and full-bodied Linear PCM 2.0 stereo. The one on Straight Shooting was composed by Michael Gatt and is largely piano driven with occasional acoustic guitar accompaniment, the sort of music you might expect to hear played in a provincial cinema when the film first screened. The score on Hell Bent is by Zachary Marsh and more what I’d think of as a traditional silent movie score, one that employs a wider range of instruments and really accentuates the comedy of the early scenes.

STRAIGHT SHOOTING

Audio Commentary by Joseph McBride

Searching for John Ford author Joseph McBride delivers a busy and consistently interesting commentary that for the most part avoids deconstructing individual scenes in order to take a wider view of the film, its director and the key cast members, with pauses to appreciate specific aspects of the filmmaking. Areas covered include Ford’s eye for composition, the emotive use of doorways in his films, the striking Beale’s Cut location, Ford’s stock company of actors, his interest in the Old West, the notion of the imperfect hero, the film’s realistic and naturalistic touches, leading man Harry Carey, and plenty more. McBride notes that the climax was likely influenced by D.W. Griffiths’ The Birth of a Nation, that the film is really about Cheyenne Harry’s inner struggle, and also has words to say about the film’s dual endings. A most useful companion to the film.

Kim Newman on Harry Carey (22:02)

The venerable Kim Newman takes a break from the field of expertise for which he has become most famous (that’s horror if you’re new to film appreciation) to provide a detailed look at the film career of lead player Harry Carey, particularly the 20-something films he made with Ford in the space of four years, before the two parted company and went their own independently successful ways. There’s some minor crossover with Joseph McBride’s commentaries, but the ground is covered in more detail here and this is thus a most welcome inclusion.

Bull Scores a Touchdown (10:42)

The first of two useful video essays by film scholar, Tag Gallagher, is unsurprisingly focussed on Straight Shooting, though does include some background detail on Ford and his many early collaborations with Harry Carey. Of particular interest are the instances he highlights where Ford has given actors little bits of business to humanise their characters and his use of foreground objects to give depth to his framing.

Hitchin’ Posts (1920 – fragment) (3:11)

A tantalising snippet from an otherwise lost John Ford film in which Southern plantation owner Colonel Brereton (Mark Fenton) loses his race horses to successful riverboat owner and gambler Jefferson Todd (Frank Mayo) in a card game. Even in this three-minute segment, Ford’s filmmaking chops are clearly evident, in the purposeful use of close-ups, the subtle poignancy of the impact of the loss on Brereton, the exquisite sundown exterior shot of the riverboat, and even the emotive use of his signature darkened doorway.

HELL BENT

Audio Commentary by Joseph McBride

This second commentary from Joseph McBride takes its cue from the first, highlighting elements that illustrate Ford’s painterly eye for composition and the similarities to, and stylistic differences from, Straight Shooting. Areas covered include Ford’s use of low and high horizons (which include terse comments he once made to a young Steven Spielberg), the film’s gay humour undertones, the tenderness of Ford’s handling of the central romance, why he deliberately flouted the standard rules of screen direction, the symbolic role of fences in his films, the reasons for Ford and Carey’s eventual parting of ways, and much more. He also highlights Carey’s habit of putting his left hand on his right arm in moments of reflection, a gesture that John Wayne (who apparently modelled his screen image on Carey) copied in the iconic final shot of The Searchers.

John Ford Interview (44:32)

This is a valuable and fascinating inclusion, though not just for the reasons you might expect. Recorded by Joseph McBride in 1970 when he was just 22 years of age and researching his first book on John Ford, this audio interview with the director at the end of his filmmaking career was made for research purposes and is allowed to play here in its entirety. There’s a sizeable, scene-setting introduction by McBride in which he comments on Ford’s irascibility and the flippancy of some of his answers, but he also admits that this was his first Hollywood interview and that his technique improved considerably over time. Ford himself lives up to this introduction, his partial deafness prompting him to repeatedly bark, “UH?” at McBride, and while some of his responses are interesting in their detail, McBride’s inexperience as an interviewer does sometimes show and it’s easy to see why Ford sometimes gets a little impatient (and I’ve absolutely been where McBride is here when interviewing filmmakers about their work). Ultimately, it’s Ford’s irritation that proves most entertaining. When talking about the documentary film he supervised in Vietnam (the war was still in progress at this point), his response to McBride’s question about whether he was at risk is, “Well, when people shoot at you, it’s liable to be dangerous,” while his reaction to being told something that appeared in a column written by Peter Bogdanovich is a curt, “Bogdanovich is full of shit!” He finishes up by saying to McBride, “This is a really lousy interview,” which must have really stung at the time, then qualifies his statement with, “All you people, you all ask the same questions and I’m sick and tired of trying to answer them. I’m just a hard-nosed, hard-working ex-director, and I’m trying to retire gracefully.” Despite Ford’s irritation and reticence, I really enjoyed listening to this, but do wish it hadn’t been accompanied by a single image that stays on screen for the entire 44 minutes, as it’s something that gives those of us with screens that are prone to burn-in the heebie-jeebies.

A Horse or a Mary? (9:14)

In his second video essay, Tag Gallagher provides a brief biography of Ford and touches on the members of his stock company that appear in the two films in this set before focussing on Hell Bent. Areas covered include the absence of the first film’s foregrounding of objects for depth, the use of the Remington painting and the Beale’s Cut location (which for some reason is shown in a postage stamp-sized photo), and more. He claims that horses are always galloping in the film (this feels oddly like a complaint) and also suggests that as much as 20 minutes may be missing, something I’ve not been able to confirm either way.

Also included is a Booklet that contains a compellingly detailed essay on Carey, Ford and Straight Shooting (including its relation to Hell Bent) by Richard Combs, an informative one by Tag Gallagher that reads a little like a literary version of one of his video essays, and a solid examination of Hell Bent by Phil Hoad. Also included are the main credits for both films and the expected viewing notes, and the booklet is illustrated with film stills and publicity imagery.

Two important rediscoveries from the dawn of a great director’s long and distinguished career that also happen to be cinematically compelling and enjoyable entertainments. Both have been restored to as good a level as we’re ever likely to see and have been packaged with informative and insightful commentaries, video essays and interviews, plus the usual high quality Eureka booklet. An absolutely must for anyone with an interest in the development of the western and the work of one of its finest exponents. Highly recommended.

|