|

John Ford is a filmmaker so well known for a handful of genuine classics, most of them westerns, that the fact that he made over 140 films in a wide range of genres over the course of his 60-year career as a director is too rarely acknowledged. Many were made in the silent era, some were documentaries, a few were short films, and the vast majority will probably never be seen by any but the most devoted of Ford fans (even then, many of his silent films have since been lost). A good many of these films, however, have been unfairly neglected, partly due to a tendency on the part of some writers to focus on the most well-known and widely heralded titles. Mind you, the reverence that some have for Ford also means that claims will inevitably be made for the greatness of films and elements in them that would not be so enthusiastically championed had Ford's name not been on the opening credits – you'll certainly find more than a whiff of that in the extra features here. But that's perhaps inevitable when you make that many movies and many of them become the subject of learned books and articles, and your work is championed by a slew of filmmaking giants, including Ingmar Bergman, Kurosawa Akira, Jean-Luc Godard, Sam Peckinpah, Orson Welles, Satyajit Ray, Martin Scorsese and Stanley Kubrick, to name but a few.

The four films in this collection were all directed by Ford during his time working for Columbia Studios, and cover the period laid out in title of this box set. Only one struck me immediately as an instantly recognisable Ford film and none of them are westerns – The Whole Town's Talking is a mistaken identity comedy-crime movie; The Long Gray Line is a large scale life story biopic; Gideon's Day is a British character study dressed up as a police procedural; and The Last Hurrah is a drama about an old-school town mayor's final campaign. All are fascinating for varying reasons and all are absolutely worth seeing, and while some will enthusiastically embrace all four, others will find themselves preferring one or two titles over the others. That was certainly the case with me, and as ever, my comments are personal reactions and not to be taken as anything approaching film gospel, and you'll find plenty of alternative opinion in the special features.

As ever with Indicator, the films themselves are handsomely presented and adorned with special features, all of which have ensured that this review has taken far longer than its content really merits. Anyway, enough of this introductory waffle and on to the films themselves, which I've covered in chronological order.

| THE WHOLE TOWN'S TALKING (1935) |

|

Arthur Ferguson Jones (Edward G. Robinson) is a meek and fastidious company clerk with a secret obsession with sassy office girl Miss Clark (Jean Arthur). One morning, his supervisor Spencer (Arthur Byron) is ordered by company boss J.G. Carpenter (Paul Harvey), who is fed up with the poor punctuality of his employees, to fire the next person who comes in late, but also to give the only employee who has never been late a raise. Care to guess who that ever-punctual staff member is? And while you're at it would you like to have a stab at who manages to be late for the first time in his eight years of employment with the company that morning? It turns out Arthur's unreliable new alarm clock is to blame, and when he tries to sneak in to work he's collared by Spencer, who now has the dilemma of having to both fire him and increase his salary. He elects to do neither and instead fires Miss Clark when she rolls in even later, a decision she responds to by not giving a hoot, plonking herself down at her desk and burying her head in a newspaper. It's here that one particular story catches her eye, or more specifically the picture that accompanies it. A notorious and dangerous gangster named 'Killer' Manion has escaped police custody and is being sought by every cop in the city. And wouldn't you know it, he's a dead ringer for the humble Arthur. Can you guess what happens next?

That Arthur will be mistaken for Manion is inevitable – after all, why introduce such an unlikely plot point if you're not going to make use of it? – but the scale of the response is still a lot of fun. He's just been joined in a diner by the bubbly Miss Clark when his similarity to the newspaper picture alerts fellow diner Hoyt (familiar face Donald Meek, who once again live up to his descriptive surname). He calls the police, who arrive at the diner in Blues Brothers force and march the terrified Arthur off to the station, dismissing his every assurance that they have the wrong man and that his real name is Jones. While they're at it they also arrest Miss Clark under the impression that she's Manion's moll, and while Arthur is squirming and pleading his innocence, Miss Clark thinks the whole thing is a blast and plays up to the roll she's been given, acting the tough broad and blaming every job her interrogators bring up on Manion. You just know that sooner or later the cops are going to realise their mistake, but Jo Swerling and Robert Riski's smart screenplay throws in more barriers to this goal than you might expect, with company boss Carpenter not recognising Arthur because he doesn't know the faces of any of his minions (sounds about right). A false positive ID is then provided by a Manion henchman named 'Slugs' Martin (Edward Brophy), who's initially terrified of fingering his boss then acts all tough when he realises the man he thinks is him is securely in police custody. Oh, you're going to regret that particular outburst, mister. Eventually, Manion himself lends a hand by robbing a bank whilst Arthur is in custody, and after debating locking Arthur up until Manion is caught (probably a good idea, as it happens), the commissioner instead gives him a signed letter to show to any policeman who misidentifies him as Manion, then rather carelessly sends him on his way. What could possibly go wrong with that plan?

The Whole Town's Talking is an odd and in may ways atypical film Ford, the setup having more of a Frank Capra vibe, and while it's an often neglected and even casually dismissed entry into Ford's early filmography, it has its staunch defenders (some of whom are on this disc) and currently has a user rating on IMDb equal to that of the director's later classic She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. Woah, hold on there. Seriously? There's no question that The Whole Town's Talking is a good deal of fun, has a sprinkling of genuinely delightful moments and a belting lead performance that I'll get to that in a minute. Yet despite the infectious enthusiasm of knowledgeable fans like Leonard Maltin and Sheldon Hall (see below), I found myself struggling to engage with the film as completely as I should have given my fondness for fast-talking 30s American comedies. I'm normally a sucker, for instance, for self-confident, wisecracking women, and Jean Arthur's performance as Miss Clark here is definitely one of the film's key strengths (it seems only logical that she would subsequently find fame playing a similar role in two hugely successful Frank Capra movies). Yet while Jean Arthur herself certainly gives it her all, for me her dialogue was never quite as sharp as her character deserved, resulting in the sassy delivery of lines that are neither as witty nor as cutting as her fellow film characters seem to think they are. The lack of narrative surprises, meanwhile, is accentuated by pacing that intermittently shifts into lower gear and whose more energetic spurts are rarely as seductively dizzying as you feel they could have been in the hands of Capra, Hawks or even Lubitsch.

What makes the film special regardless, however, is Edward G. Robinson, whose dual performances as Arthur Ferguson Jones and 'Killer' Manion are so distinct from each other that I was well into the film before I realised that I had never once given any real thought to the fact that they are played by the same actor. I've read it claimed that Robinson was attracted to the role of Arthur in part by the opportunity it gave him to break away from the tough guy roles for which he had become known while simultaneously revisiting the sort of persona the public would expect from an Edward G. Robinson film. In this respect he gave the public what they wanted whilst also showing them he was capable of so much more as an actor. And it's as Arthur that he shines the brightest here, utterly convincing and sympathetic in his bumbling shyness and deftly effective in his more comical moments. So completely does he sink himself into both roles and so different are they to each other in character, despite their identical appearance, that there were times when I caught myself genuinely worrying about what Robinson as Manion might do to Robinson as Arthur.

While it's definitely Robinson's dual central performance that makes this uncharacteristic Ford feature well worth a look, the director's eye for offbeat detail and and the technical handling is also noteworthy: the reporters who buzz excitedly around like a swarm of hungry mosquitos; the comically loud squeak of Arthur's shoes as he heads nervously to a meeting with Carpenter; the manic speed at which the traditional newspaper headline montages unfold. Particularly impressive is the split-screen work that places Arthur and Manion in the same shot together, at its most startling when Manion hands the commissioner's letter to Arthur and he takes it in the same shot, or when Manion's cigar smoke drifts past what must have been the invisible matte line into Arthur's space. Less convincing is the use of back-projection to place the two in the same shot (the back projected image is noticeably fuzzier and has softer contrast), but even this is put to inventive use when Arthur looks in the mirror and Manion walks up behind him in the reflection.

The Whole Town's Talking is an engaging and often lively tale with a terrific central performance, solid support across the board and a sprinkling of standout sequences. There's also a fast-pan visual gag towards the end that made me laugh out loud, once again involving Arthur and the police and that I could almost swear was an influence on John Landis and the aforementioned The Blues Brothers. Yet when the film was over there was, for me, still one burning question left unanswered – who turned off the bath water left running and overflowing when Arthur dashed out after realising he was late for work?

Sourced from a 4K remaster by Sony, supervised by Michael Friend, the 1080p, 1.37:1 transfer here may not be quite as razor-sharp as some of the very best restorations of this period, but it's still in great shape, with a very strong level of picture detail, solid black levels and a generally well-balanced tonal range. Film grain is visible and I didn't spot any significant instances of dust or damage. Of course, the increased definition does make the back-projection work stand out more, but that's par for the older special effects course.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack has the sort of range restrictions that are standard for films of this period, but the dialogue is always audible and there's no trace of background hiss or fluff.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available.

Cymbaline (6:15)

A short video essay by Tag Gallagher, author of John Ford: The Man and His Films, one that finds meaning in the geometry of sets and framing that may or may not have been intended and makes observations about the class structure hierarchy that either should be clear to all or are open to alternative explanation. Gallagher really knows his Ford films, but I'm still not completely sold on some of the points made here.

Leonard Maltin on The Whole Town's Talking (6:03)

Critic and film historian Leonard Maltin praises the qualities of what is often seen as a throwaway film for Ford, giving special shouts to Edward G. Robinson, Jean Arthur and cinematographer Joseph August's sophisticated in-camera split-screen effects work.

Sheldon Hall: A Trip Outside Ford Country (22:26)

Film historian Sheldon Hall takes a detailed look at a film he describes as something of an anomaly in Ford's filmography, discussing its expressionist elements, the use of photographs and clocks function as motifs, the special effects, the screenwriters, the lead actors, the use of doppelgängers in 30s movies, and more.

Pamela Hutchinson: No Rules But Her Own (17:56)

Critic and film historian Pamela Hutchinson provides a high-speed and information-packed look at the life and career of the film's co-star, Jean Arthur, from her early work as a model to her career-defining films for Frank Capra and her memorable final screen role in George Stevens' Shane. Her reputation for being difficult is examined, as are her ahead-of-their-time feminist views and a level of insecurity that sometimes saw her abandoning stage productions early in their run. I learned a lot from this.

Lux Radio Theatre: The Whole Town's Talking (52:30)

A Lux Radio Theatre version of the play, first broadcast on 24 February 1941 and starring the husband and wife team of Jim and Marion Jordan, who here are credited as Fibber McGee and Molly, the names of their then-popular radio personalities. It moves at a lightning pace and for the most part it closely follows the film's lead, though with some notable changes. The most prominent of these is that Arthur and Miss Clark have had name changes to Wilbur and Jessie and the two are engaged to be married from the start, presumably to capitalise on the actors' existing radio personas, which is probably also the reason that Wilbur is more of a gag-driven smart-arse than Arthur. Cecil B. DeMille is on hand to provide a sincere introduction and talk about the properties of Lux soap. Pleasingly, this plays out under a black screen to avoid burn-in on sensitive televisions.

Image Gallery

19 screens of promotional photos, front-of-house stills and posters, the best of which by far is the French one under the title Toute la ville en parle.

Booklet

Following full credits for the film we have an essay by film critic and writer Farran Smith Nehme – who also contributes to the commentary for The Long Gray Line – who sings the praises of a film I enjoyed but she clearly adores, and in impressively analytical detail. Next up, we have an extract from the serialised story by William H. Burnett on which the film was based, which is written in the sort of style that instantly made me want to read the rest of it. An excerpt from Edward G. Robinson's autobiography All My Yesterdays follows in which he looks back at how he ended up making the film, after which we have a mix of contemporary reviews and later reappraisals – intriguingly, Monthly Film Bulletin saw it more as a thriller than a comedy, the reverse of how it was viewed on home turf.

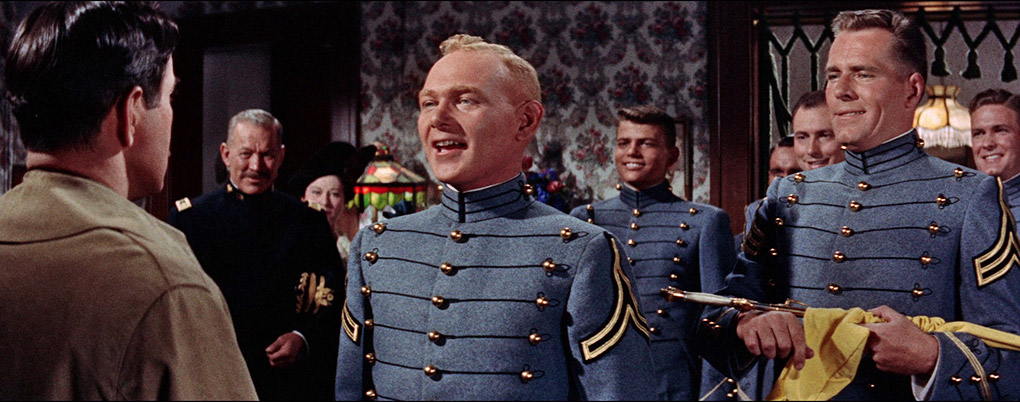

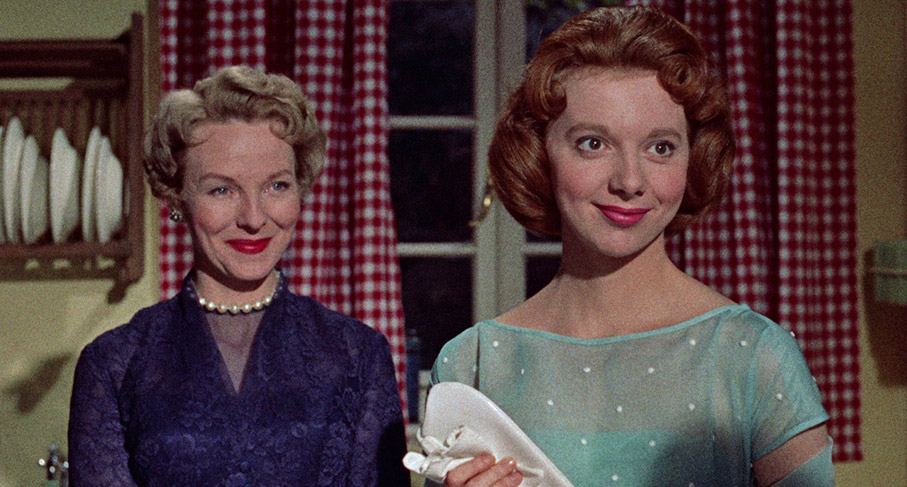

| THE LONG GRAY LINE (1955) |

|

Of all the four films in this set, The Long Gray Line is unquestionably the most recognisably Fordian. The first half-hour is as riddled with comically exaggerated Oirish blarney as any similar length segment from Ford's Ireland-set The Quiet Man, and when it shifts in tone to become a more serious-minded character study, it celebrates the notion of military camaraderie and the substitute family element of soldiery as warmly as any of the films in the director's celebrated Cavalry Trilogy. Whether it climbs to their considerable heights as a movie is likely to be a matter of personal opinion.

The film tells the loosely-based-on-fact story of Marty Maher (Tyrone Power), a fresh-off-the-boat Irish immigrant who in 1898 rolls up at the front gate of West Point, America's foremost military officer training academy, to work as a butler in its dining hall. Quite why he's kept on is anybody's guess, as he breaks so much crockery that three months after he started he's still not drawn a wage due to deductions made to cover the damage. When he learns that cadets aren't financially penalised in the same fashion he decides to enrol and initially proves to about as hopeless as a trainee soldier as he was as a butler. His fortunes and attitude are changed, however, when the tough, no-nonsense Captain Koehler (Ward Bond) takes him under his wing, but by then he has a new distraction in the shape of the Koehlers' pretty young Irish housemaid Mary O'Donnell (Maureen O'Hara), whom he actively pursues but who initially behaves as if he doesn't exist.

I could go on and detail how things pan out for Marty over the course of his 50-year career at West Point but, save for a couple of effectively handled surprises, much of what happens plays out as expected and the film itself signals some turns of fate well before they occur. Part of this is no fault of Ford or the unfolding story but the simple fact that even by 1955 we'd sort of been here before. I was probably only about halfway into the film when it dawned on me that it was playing in some ways like a reworking of the 1939 classic Goodbye Mr. Chips, with the action transposed from a prestige English public school to America's top military academy. I am, of course, far from the first to spot this connection and it's even been used by some as a put-down in their dismissal of the film, something the contributors to the commentary track take real issue with. Yet the similarities are numerous and hard to ignore. Not only are the films situationally similar, but so are some of the key character details. Both films are essentially flashbacks to a full life lived primarily within rule and tradition-based seats of learning whose students are conditioned to be either societal or military leaders, and both are framed by scenes featuring the central character as an elderly man looking reflectively back on his life. And as well as looking increasingly like his forebear as he ages, the elderly Marty follows in his footsteps by telling students that he taught their fathers and grandfathers before them. As the film unfolds, some of the story beats here will also ring a bell with anyone who knows the earlier film, details of which I'm choosing not to reveal as this would mean delivering some major spoilers. It's also worth noting that some of these plot points were not drawn from the real Maher's life but were inventions of scriptwriter Edward Hope, who may well have taken inspiration from cinematic as well as literary sources.

This was Ford's first film in CinemaScope and apparently he hated this aspect ratio (which I presume was forced on him by the studio, otherwise why use it?), but cinematographer Charles Lawton Jr. (who went on to work repeatedly with Ford, including on one of the other films in this set) still makes eye-catching use of the wider aspect ratio to frame parades and crowd scenes in a manner that really showcases their scale and makes it all too clear that the film was shot on location at West Point using actual cadets as extras. That said, I couldn't help wondering if Ford's discomfort with the format is at least partly responsible for the film's paucity of closeups and fondness for capturing whole sequences in expansive wide shot, the camera occasionally holding its position when the emotion of a scene would normally call for it to move in closer. Mind you, there are still a whole string of moments that have Ford written all over them, in their framing, their emotive use of light and their positioning and movement of characters within the frame, and you'll find several examples of his knack for balancing the comic, the dramatic and the tragic and his ability to dovetail one smoothly into the other.

As a based-on-fact life story, The Long Gray Line ticks all the expected boxes, from the gradual ageing and emotional evolution of the main character (the makeup on this score is convincingly done) to a running time that would have been considered long for film of its day. How fully you respond to it may depend in part on how many other such tales of a life fully lived you have seen and how fond you are of them. The first half-hour will certainly tickle some, and I have a feeling I'd have been more seduced by it had the blarney been toned down a notch and some of the physical gags not relied on unlikely setups. A prime example of this is when Marty walks into the kitchen and falls arse over tit, sending the plates he was carrying smashing to the floor, an accident that only occurs because the steep ramp leading from the dining hall to the kitchen was being scrubbed with soapy water as he entered. Quite why the kitchen would be lower than the dining hall and why a steep ramp would be positioned just inside the door through which plate-carrying butlers have to hurriedly walk is anybody's guess, and I do have to question the intelligence of anyone who thought that the best time to scrub said slope with slipper water was in the middle of meal time for hundreds of cadets. As a setup for a gag in a silent slapstick comedy it's par for the course, but a supposedly based-of-truth drama? Sorry, no sale.

Yet if you have no problem with this, and I'm sure many won't, and you don't mind the retro ground and occasional drifts towards sentimentality, there's still much to enjoy and admire here. While the emotional hits can be sometimes be seen coming they're still effectively handled, and if you do embrace Marty's story then you're likely to find yourself getting quite emotional at times. Filming on location at West Point, meanwhile, gives scenes involving large numbers of cadets a real pre-CGI grandeur (the sheer number of people in the dining hall wide shots is breathtaking) and despite the early comical exaggerations, Tyrone Power really delivers when it counts, his emotional pain at personal tragedy and his later indignation at derogatory comments made about the academy have genuine conviction. The supporting cast, as ever with Ford, is also peppered with delights, with Ward Bond a standout as Master of the Sword, Captain Koehler, and those with a nose for American history may well delight at the sprinkling of famous real-world names that appear amongst the staff and graduates. In the end, The Long Gray Line is a film I probably admired more than I enjoyed, but I definitely enjoyed it, just not quite as a much as those who sing its praises in the special features. And while most definitely the story of a man and his life, the film itself, very much like its central character – who at one point bemoans the wastefulness of war and repeatedly makes plans to resign his post only to then change his tune – is ultimately won over by the Academy and what it stands for.

Sourced from a Sony 4K remaster supervised by Michael Friend, the 2.55:1 transfer here is seriously impressive, with fine rendition of detail and a well-balanced contrast range with strong black levels but decent shadow detail, and while the palette does have the look and hues of many Technicolor films of the period, the colours are still most attractively rendered. A fine film grain is visible and all dust and damage has been cleaned up.

If you're someone who tends to just go with the default track on discs of older movies (which tend to have a single mono track anyway), here's one time when it's worth investigating that Audio Setup button on the menu. Here you're offered the option of Linear PCM 2.0 stereo or DTS-HD Master Audio 3.0 stereo, and while the default PCM track is in excellent shape, the DTS track is even better, having more breath and oomph on the music and louder sound effects, as well as even more robust bass response. As you would expect, the dialogue tends to emerge from the centre speaker on the 3.0 track and be spread across the front sound stage on the 2.0. Both are clear and lively without any trace of issues and both boast a very impressive dynamic range for a film of this vintage.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are present.

Audio Commentary with Dianna Drumm, Glenn Kenny and Farran Smith Nehme

Film critic and writer Farran Smith Nehme, together with film reviewers Glenn Kenny and Dianna Drum – the last of whom knew Maureen O'Hara in her later days – get together to sing the praises of a film they clearly regard as one of Ford's finest. There's a lot of ground covered here and Kenny broadens things further with pertinent and sometimes revealing quotes from Tag Gallagher's John Ford: The Man and His Films and Harry Carey Jr.'s autobiography, A Company of Heroes. There's plenty on Tyrone Power, although when asked about the authenticity of his Irish accent, Drumm pauses a moment before describing it as "passable," adding that she's heard worse, which I'd say was fair. As ardent fans of both Ford and the film, they do occasionally fall into the auteur trap of reading genius into aspects that any director worth his or her salt would have handled similarly, but they also highlight a number of elements that are absolutely deserving of praise.

Living and Dead (16:48)

The second of four video essays by Tag Gallagher examines Ford's use of the scope frame, how the film bears scant resemblance to it's source material and why it can be read as "a glorification of life in the illumination of death," which I thought was a rather poetic description of its qualities. There are a number of observations made here about the film and the journey of its central character, some obvious, some questionable, but some genuinely interesting. I got a lot more out of this essay than I did out of the previous one.

Leonard Maltin on The Long Gray Line (5:43)

Maltin begins his positive appraisal of the film with a warning about the level of Irish blarney you'll have to deal with in the first half-hour, then admits that it ultimately won him over. He examines the point at which the film takes its first serious turn, highlights some of the specifically Fordian moments, notes the director's hatred of CinemaScope and the work of cinematographer Charles Lawton Jr., and more.

The Red, White and Blue Line (1955) (10:01)

What seems to start as a promo for the film eventually reveals itself to be a patriotic ad in which some of the key cast members – including Tyrone Power and Maureen O'Hara – eventually talk to each other and the audience in character about the importance of buying savings bonds. Time has rendered this aspect a tad cheesy, but this is still a valuable grab for its inclusion of a deleted scene in which Marty injures his finger when trying to impress the still aloof Mary and she dresses it for him, a process that includes spitting on the wound. Oh, how hygiene standards have changed. Narration is provided by Ward Bond.

Theatrical Trailer (4:27)

A self-proclaimed "preview of scenes" from the film that does include one small spoiler and is heralded as John Ford's "masterpiece" and "his finest picture." I'm going to have to take issue with you on that point, Sir.

Image Gallery

17 screens of promotional stills, behind-the-scenes shots (these will be of particular interest to Ford fans) and posters.

Booklet

After the film credits this booklet kicks off with an essay by writer Nick Pinkerton, who highlights praiseworthy elements of the film and examines it in the context of John Ford's fascination with the military ethos. Next are some extracts from Maureen O'Hara's autobiography, 'Tis Herself, in which she looks back at the problematic relationship she had with Ford during the making of this, their fourth film together, and provides specifics of his on-set cruelty, which included his insistence on loudly greeting her each day with, "Well, did Herself have a good shit this morning?" This is followed by a 1955 article from Cinémonde by critic and film theorist Jean Miltry detailing a meeting and conversation he had with John Ford, and two less than complimentary contemporary reviews and an extract from a 1976 monograph by Andrew Sarris in which he re-examines the film.

Films built around a typical day in the life of a single individual have their work cut out for them if they're going to hold the attention of an audience that is used to watching a single story unfold with one set of characters rather than snippets of several narratives in progress involving a large number of people. This problem is effectively negated if the premise is the basis for a single episode of a TV series. Take the season 4 episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation titled Data's Day, which became a fan favourite despite breaking with the show's usual format to stick exclusively with the Starship Enterprise's resident android Data as he spends a typical day interacting with his fellow crew members and solving problems, all of which he comments on in the manner of an audio diary. This episode works precisely because it is part of a long-running TV series, one that had by this point spent over three seasons getting its audience familiar with the characters with whom Data interacts, and thus works by presenting familiar situations from a different viewpoint. Make Data's Day the first episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation that you watch and you're likely to be left utterly bemused by much of it and be ill equipped to appreciate what the episode does so well.

Probably the most successful example of a feature film take on the format in recent years is the Coen Brothers' Hail, Caesar!, which on the surface plays almost like a series of loosely connected tales that unfold in a Hollywood studio in the 1950s and indeed has been negatively judged by several commentators for being just that. Yet take a step back and it becomes clear that it's actually the story of a day (well, OK, a day and a half) in the life of studio fixer Eddie Mannix, a man of extraordinary patience and commitment who deals with a whole series of potentially catastrophic problems without fuss of fluster (except when feigning anger is the only way to get through to a dopey star), popping home midway through to his understanding wife and at the end calmly heading off to face what we can presume is another day of the same. After watching the 1958 Gideon's Day, the only British film directed by the very American John Ford, I couldn't help wondering if the Coens had taken some inspiration from it. The setting and location and the temperaments of the lead characters may be different, but in other ways the titular Gideon, a chief inspector at London's famed Scotland Yard, has a fair amount in common with Mr. Mannix.

Initially Ford follows (or perhaps helps to start) the tradition of American directors shooting in London with an opening credits sequence plastered with the usual icons – Big Ben, Tower Bridge, red double-decker buses – to the accompaniment of a jovial orchestral version of London Bridge is Falling Down. OK, got it, we're in London. The opening domestic scene of Gideon (Jack Hawkins) at home at the start of his day also has its share of familiar elements for the day, from his wife Kate (Anna Lee), who dutifully and cheerfully prepares everyone's breakfast, to his eldest daughter Sally (Anna Massey), who dives into the bathroom when Dad pops out mid-shave to tell his wife he's running late. By the time he reaches work he's not in the best of moods, having had an ominous call at breakfast from a cockney informant with the unlikely name of Birdie Sparrow (Cyril Cusack) and been given a ticket for jumping a red light by eager young police constable Farnaby Green (Andrew Ray), which frankly sound more like the name of an underground station. It's here we meet his assistants, Detective Sergeant Liggot (Frank Lawton) and Sergeant Golightly (Michael Trubshaw), another comically slanted name in a film that seems to delight in them. These two are probably the most Fordian characters in the film, particularly Golightly, a very British stand-in for Victor McLaglen's Irish sergeants and whose regimental moustache and military countenance may irritate Gideon but had me bouncing in my seat with glee.

In common with Eddie Mannix in Hail, Caesar!, the suggestion that this is a typical day for Gideon is a bit of a stretch. Just as Mannix had to deal with the kidnapping of the studio's top star – hardly an everyday occurrence – alongside many other trials and tribulations, here Gideon oversees the investigation and resolution of a violent robbery, a handful of murders and a serial killing, has to suspend a fellow officer for taking bribes and is held at gunpoint in a confrontation that could easily have resulted in his death. He also has to rush to make a court appearance where he's only required to say a single word. And yet at the end of this long and fraught day he heads home with the resolute air of a man for whom none of this is remotely unusual. It's no wonder he arrives at work in a temperamental mood.

The performers are a key attraction here, with Jack Hawkins perfect casting as the irascible Gideon, with the actor's ability to irritably growl out his lines put to excellent and sometimes comical use. There's strong support (in her feature film debut) from Anna Massey as his lively and self-confident teenage daughter Sally, and particularly from Grizelda Hervey as the emotionally broken wife of the officer charged with corruption. And while Andrew Ray may at first seem like exaggerated casting as Farnaby Green, looking as he does too young and delicate to take seriously as a beat cop, he's not sidelined as the comic irritation he's initially set up as, being sharp enough to spot a crucial clue to the identity of the serial killer (played by old favourite Laurence Naismith) and confident enough to follow and confront the man. That he also catches Sally's eye and ends up dating her ensures that in spite of his accomplishments he remains a small thorn in Gideon's side, though there is the sense here of an acknowledgement on Ford's part that the next generation, annoying though it may be, might just have the talent to step into the shoes of its experienced elders after all. Even the smallest speaking role is carefully cast to make an impression, as evidenced in the brief courtroom scene, where the judge is played by familiar face Miles Malleson and the prosecuting barrister by a blink-and-you'll miss-him John Le Mesurier.

As with Hail, Caesar!, the diving from case to case does result in some tonal shifts that can at first feel a little ramshackle, but in common with its successor this does give rise to some memorable sequences. The most chilling of these involves serial killer Arthur Sayer, who has travelled down from Manchester to visit welcoming relative Mrs. Saparelli (Marjorie Rhodes), who trusts him enough to leave him alone in the house with her teenage daughter Dolly (Hermione Bell). The moment when Sayer picks up a cup of tea and starts walking slowly upstairs to do who knows what to the unfortunate Dolly, you could almost be watching a sequence from 10 Rillington Place, another fine and very British film with an American director. Later, when Gideon pays a commissary visit to the distraught Mrs. Saparelli and finds her sitting in the kitchen being comforted by friends, her grief is conveyed in an instant by master cinematographer Freddie Young's expressive lighting and framing. It's a sombre sequence that soberly captures one of the most difficult jobs a police officer has to do.

I've seen a couple of negative reviews of Gideon's Day, both of which suggested that this one-time relocation to London placed Ford out of his comfort zone, but I enjoyed the hell out of it. Despite the inclusion of a corrupt police officer (an aspect that apparently scuppered any cooperation from the real Scotland Yard), it's ultimately as much a cheer for the work of the British police as the same screenwriter's celebrated The Blue Lamp, but nuanced and varied enough in tone, character and incident to not play as a recruiting film. It has its odd quirks, but savvy casting ensures that every one of the fifty-plus speaking parts register, and the sheer organisational skill required to make sure we are able to keep track of all of the stories as the film flits between them is as impressive a demonstration of Ford's directorial skills as you'll find anywhere in this set. The result is a lively, enjoyable and intermittently humorous melding of police procedural and character study, one whose fragmented structure, naturalistic overlapping dialogue exchanges and energetic performances and direction made it for me the most entertaining film in this collection.

Sourced from a 4K restoration from the original negative supervised by Grover Crisp, the 1080p 1.85:1 image here betrays its age in the earthy hues of its Technicolor palette, but in other respects this is another strong transfer, impressively capturing the deliberately dour look of Freddie Young's realist-influenced cinematography, and really shining in the more visually arresting moments. Film grain is visible and again there are no signs of any former wear or damage.

When you select 'play' you are offered the option to watch the film as Gideon's Day or under the American title of Gideon of Scotland Yard. Main title aside, there appears to be no difference – the running time is identical and both are in colour, so don't expect the cut down, black-and-white version that Leonard Maltin talks briefly about in the extras.

The DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 mono soundtrack has the expected range restrictions but is otherwise clear and free of damage.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired have been included.

Audio Commentary with Charles Barr

Film Professor Charles Barr may not have the vocal enthusiasm of some of the other commentators in this set but he knows his stuff and communicates plenty of real interest, highlighting aspects of the director's style, deconstructing specific elements of certain scenes, giving information on the actors, filmmakers and locations, and more. He almost offhandedly reveals that source novel author John Creasey was not a fan of this film, provides specifics on how the movie came to be, looks back at the time of cinema double-bills and rolling programmes (for which I am also a tad nostalgic) and even suggests a few intriguing possible influences on Hitchcock's Marnie.

The BEHP Interview with Freddie Young

An audio-only interview with top cinematographer Freddie Young, conducted by Roy Fowler and Alan Lawson on 1 April 1987 and 14 August 1987, in which Young looks back at his career, covering his early work as a lab technician and his move into cinematography in considerable detail. Perhaps inevitably, the film that gets the most coverage by far is Lawrence of Arabia, though this also triggers an interesting story about having to shoot some beach scenes for Ryan's Daughter in Cape Town due to Irish winter weather and having to paint the white rocks black to match the ones back in Ireland. Unsurprisingly, he cites David Lean as his favourite director to work for and is less enthusiastic about Michael Powell, whom he describes as "all right, but a bit of a tyrant." There's tons of interest here, including plenty of technical information on lighting and pre-exposing film for those interested in these things (that would be me), and it ends amusingly when Young is asked which cameraman gave him the most help when he was starting out, and he replies without a pause, "None of them."

Milk & Sugar (9:11)

The best yet of Tag Gallagher's video essays highlights how much ground is covered in the film by listing the crimes solved and noting that Ford tells a dozen stories during the course of 95 minutes with 50 speaking parts whose characters all instantly register due to the care that was taken in the casting. Aspects of Gideon's character are examined, particularly his short temper and his reliance on his pipe as a prop, and I really liked the quote from Anna Massey that describes the perennially pipe-smoking Ford as looking "rather like a larger, softer version of Popeye," which I couldn't resist nabbing to title this review.

Elaine Schreyeck: Meet the Wife (5:33)

The film's continuity supervisor Elaine Schreyeck recalls being told to shut up and go away by Ford early on in the production, then being used to prank visiting actors and technicians by him later when he would introduce her with the phrase, "meet the wife." She recalls being challenged by Ford after correcting cinematographer Freddie Young over a setup that crossed the line of action, and briefly comments on actor insecurity and working with screenwriter T.E.B. (or as everyone her calls him, Tibby) Clarke.

Leonard Maltin on Gideon's Day (3:28)

A brief but busy appraisal of the film by Leonard Maltin, who highlights the work of cinematographer Freddie Young, how well written T.E.B. Clarke's screenplay is, how effective Jack Hawkins is in the lead and how there isn't a wasted moment in the film. He also reveals that Columbia's American division weren't impressed with the result and released it in the US in black-and-white with a title change and with cuts to the running time.

Adrian Wootton: A Day to Remember (28:16)

Author and BFI film season curator Adrian Wootton makes a passionate and persuasively argued case for why Gideon's Day deserves to be remembered as so much more than the footnote in Ford's career that it seems to have become. As the running time might indicate, he covers a lot of ground, with specific attention paid to author John Creasey, the work that must have been required to shoot on so many locations, the top-rank names both in front of and behind the camera, the elements that identify it as a Ford movie, and a hell of a lot more. It's a terrific piece that as a fan of the film I found myself in full agreement with on every point.

John Ford and Lindsay Anderson at the NFT (4:29)

Silent footage of John Ford visiting London's National Film Theatre (now BFI Southbank) in the summer of 1957 during the production of Gideon's Day and chatting with Lindsay Anderson and two unidentified NFT bigwigs. Interestingly, when Ford exits the building, queuing patrons don't appear to realise who has just appeared in front of them. A really valuable archive piece, but boy did people like to smoke back then.

Gideon's London (3:33)

A tour through some of the London locations used in the film using film clips and captions rather than a side-by-side comparison with how they look today. Includes further details of some locations, particularly those that have since closed down.

UK Theatrical Trailer (2:29)

A lively trailer with a few potential spoilers, so not one to watch just before the film itself.

Image Gallery

17 screens of promotional stills, painfully colorised front-of-house images, press book pages and posters. I genuinely want the monochrome British quad poster on my living room wall.

Booklet

After the film credits, Robert Murphy looks at Ford's reasons for making the film, the response to the finished product (including from the studio that funded it), Ford's working relationship with writer T.E.B. Clarke, the cast, and more. Next up is an interview conducted by producer Michael Killanin with John Ford about the three films they made together, followed by extracts from Jack Hawkins' autobiography, Anything for a Quiet Life in which he looks back at his work on the film and recalls an amusing bit of banter with Ford about going to a pub for a liquid lunch. After this are extracts from Lindsay Anderson's About John Ford detailing the time he met with Ford in London during the filming of Gideon's Day. Bringing up the rear are two contemporary reviews, neither of which are exactly glowing, though one is of the cut down, monochrome American version.

There's probably a case to be made for describing The Last Hurrah as John Ford's reverse-Capra movie and if that term seems clunky then know that I'm deliberately avoiding suggesting it's an anti-Capra movie because it certainly isn't that. Allow me to clarify. Where Capra's Mr. Smith was an idealistic young newcomer to politics who directly confronted the corruption of Washington, Ford's Frank Skeffington (Spencer Tracy) has been mayor of the town in which he resides for long enough to be considering retirement, and he knows just how to play the system. Frank has decided to serve just one more term before stepping down, but that does mean winning the upcoming election. His popularity with the ordinary citizens of the town means that this would normally be a foregone conclusion, but this year right-wing newspaper editor Amos Force (John Carradine), a former Klan member who has a very personal hatred of Frank, is throwing his weight behind vacuous but good-looking young family man Kevin McCluskey (a curiously uncredited Charles B. Fitzsimons). When Frank finds a way to lean on self-interested local business leader, Norman Cass (Basil Rathbone), he responds by pledging to pour as much money as needed into McCluskey's campaign. Against all odds, Frank starts to suspect he might have a fight on his hands after all.

The differences to Capra's earlier masterwork (oh come on, you don't need me to name it, do you?) also extend to the tone and content. This is not a tale of a little man battling the system and is not peppered with twists and seemingly insurmountable barriers that build to a moment of heart-wrenching triumph. As the film begins, Frank effectively is the system, or at least its representative, and over the course of the unhurried first two-thirds there are no moments that call for a dramatic chord on the score or a sudden track in of the camera on a character for emphasis. Probably the most confrontational moment comes when Frank blags his way into a private members club (using the old favourite of questioning the establishment's fire safety standards) in order to pressure Norman Cass to reconsider his refusal to grant a loan for an inner-city housing project. When Cass refuses to budge, Frank instead targets his son, tricking him into accepting a post that will allow Frank to more effectively lean on his opponent, albeit at a possible cost for his political future.

The signs in Gideon's Day that Ford was starting to acknowledge that the next generation might have something to offer seem to be on slightly shakier ground here. Frank's adult son Frank Jr. (Arthur Walsh) is a superficial twerp who takes his position of privilege for granted and has only a passing interest in his father's work. Asked by Frank on election day if he has voted, his son giggles, "This'll kill you, I forgot to register! How dumb can you get?" and heads off to his golf game without a care. Mind you, even he can't compete with Cass's son, Norman Jr. (O.Z. Whitehead), an upper-class dimwit of the highest order with a thing for uniforms and the sort of lisp later sported by Biggus Dickus in Life of Brian. The only true ray of hope lies in Frank's nephew, Adam Caulfield (Jeffrey Hunter), a morally sound and committed reporter who works for Amos Force but writes columns in support of his uncle's actions, something that Force only tolerates because it seems to boost circulation. He's nonetheless a little cautious about accepting an offer from Frank to document his election campaign, but when he does so he finds himself gradually drawn into it, which becomes the cause of some friction between him and his wife Maeve (Dianne Foster) and especially her grouchy father Roger Sugrue (Willis Bouchey), who detests Frank and everything he stands for.

One of the principal pleasures of The Last Hurrah is its dynamite cast. I was genuinely surprised to learn that Spencer Tracy was not Ford's first choice as I can't imagine any actor more suited to the role of Frank Skiffington than him, and he plays it beautifully, passionate in his anger at Cass and his cronies but really shining in the small moments of realisation and understanding. John Carradine is suitably spiteful as newspaper editor Amos Force, but is outshone here by a perfectly cast Basil Rathbone, who expertly captures that self-interested callousness that defines so many of his ilk. Jeffrey Hunter, who sat a little in the shadow of what may be John Wayne's finest performance in Ford's masterpiece, The Searchers, makes a stronger impression here as Frank's nephew Adam Caulfield, and the rest of the cast is peppered with familiar faces and a small sprinkling for the Ford stock company, including Sons of the Pioneers lead singer Ken Curtis as Monsignor Killian.

Where the film is unexpectedly forward-looking is in its commentary on how political campaigning in America was on the brink of change, with a switch from old-school 'boss' candidates to younger and more photogenic individuals who would find themselves voted into office not because of their hard work or good deeds, but because of the money thrown at them by the wealthy to fund a blitz of posters, advertisements and TV coverage. Ford mocks this here with a scene in which Kevin McCluskey, Frank's principal rival and the man whose campaign the vengeful Cass is underwriting, is filmed at home with his wife four children in an attempt to sell him as a paragon of wholesome family values. The whole thing is shown to be patently false, with scripted lines delivered in hopelessly stilted manner by McCluskey and his wife, while a dog provided by his image-makers to complete the family picture barks uncooperatively every time somebody tries to speak. It's an amusing sequence but, in retrospect, also somewhat of a sobering one, as both America and the UK are now living with the consequences of this corporate funded image-making and are both saddled at a time of world crisis with ineffectual leaders who were voted in not because of any good that they had done, but because of how effectively the false image of them played in the media.

Sourced from a 4K remaster supervised by Rita Belda, the 1080p, 1.85:1 monochrome transfer here is one of the most attractive in the set, have a very impressive level of picture detail, punchy contrast with solid blacks and a decent tonal range, and not a trace of damage or dust. I'm guessing this film was shot on low speed stock, as the film grain is easily the finest on any of the transfers in this collection.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is also in good shape, the unsurprising minor range restrictions not impacting on the clarity of the dialogue, music or background sound. There's also no underlying wear or damage.

Once again, optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available.

True Blue (7:13)

This final video essay by Tag Gallagher starts in unexpectedly factual mode with information on Ford's background, the statue of him in Portland, and how experience of anti-Irish bigotry shaped some of the lead characters in his early films. This is followed by some pertinent observations on the film and commentary on the character of Frank Skeffington.

Leonard Maltin on The Last Hurrah (4:56)

In his last piece in this set, Maltin reveals that Ford wanted to make the film as soon as he read Edwin O'Connor's novel and that the book was loosely based the life of celebrated Boston mayor Jame Curley. He doesn't mention, however, that this led to Curley successfully suing the producers of the film. Maltin also notes that the only gripe he has with the film is that those opposed to Frank are so obviously weak, but that's hardly an uncommon feature of films of this period.

Super 8 Version (19:53)

Ah, it's been a while since we've had one of these. This super-8 version for home viewing cuts the film down to a sixth of its original running time and adds a narration to fill in the story gaps that result. It hits all the major plot points but inevitably loses a huge amount of nuance and character detail, and the final scene is skipped over in a matter of seconds.

Theatrical Trailer (3:05)

An unevenly paced trailer whose narrator barks out a fair few superlatives, assuring us that Frank Skeffington is "the most unforgettable character in screen history," and that this is the greatest role of Spencer Tracy's career.

Image Gallery

22 screens of pristine promotional photos, posters and horrid coloured-in front-of-house stills.

Booklet

The lead essay here, after the film credits of course, is by writer and film historian Imogen Sara Smith, who provides some welcome detail on Mayor James Curley, on whom the character of Frank Skeffington was unofficially based, and is more willing to find fault with the film he is writing about than some of the other writers in this collection are with theirs, though also makes a persuasive case for its qualities. This is followed by extracts from a January 1958 Newsweek interview with Ford in which he talks about the film and working with Spencer Tracy, whom he describes as 'perfect', and also hints at the more controversial film he had originally wanted to make. After this, are extracts from an interview conducted with screenwriter Frank S. Nugent, who talks about working with Ford, for whom he wrote twelve films, including some of his most beloved. Finally there are three contemporary reviews, none of which are exactly gushing.

I'm not going to lie, this one has taken me an age to finish, in part because complications caused by the current pandemic and partly because I found myself wrestling with my response to each of the films and having to re-watch them and re-write the individual appraisals as my views changed over the course of several viewings. I also have a sneaking suspicion that my nationality is partly responsible for my enthusiasm for Gideon's Day and failure to engage as completely with The Long Gray Line as those on the commentary clearly did. Then again, I'm not good with cinematic patriotism at the best of times, but particularly that hand-on-heart variety that I have a feeling an American of my age might at least have a societal connection to. But having come to all four films for the first time, I was fascinated by each and enjoyed them all in different ways, and despite being directed by the same revered filmmaker, they really are surprisingly different from each other. As ever with Indicator, the presentation of the films themselves is top-notch, and special features are so rich and numerous that they have to take part of the blame for the late delivery of this review. For Ford devotees, this is a must-have, but for cineastes everywhere this is absolutely worth seeking out. Warmly recommended.

|