The following review deals with both the film and the true-life events on which it was based. There are thus some major spoilers, so those not familiar with the film or the case may want to skip to the last part of the review by clicking here.

John Reginald Haliday Christie was a quiet and seemingly unassuming man. He lived with his wife and his tortuous back pain in the ground floor flat at 10 Rillington Place in London's Notting Hill Gate from 1938 to 1953. A special constable during the Second World War, he had all the outward appearance of an ordinary, even mundane office worker. But Christie had a secret; every now and again he would lure a woman back to the house and, under the pretext of performing an abortion, would gas her into unconsciousness, and then rape and strangle her, not always in that order.

On Easter Monday in 1948, 24-year-old Timothy Evans, his wife Beryl and their young baby Geraldine moved in to the top floor flat of the house in which Christie lived.* Evans was something of a fantasist, full of blather about a supposedly wealthy background and managerial employment positions that he used to mask feelings of inadequacy regarding his illiteracy and increasing financial woes. He and his wife argued loudly and frequently, and the news that Beryl was once again pregnant did little to improve their marital harmony. Enter John Christie, the kindly old man from the ground floor flat, and the offer to perform an (at the time illegal) abortion, an operation he uses to murder Beryl and sexually abuse her body. When Christie tells Evans that the abortion has misfired and resulted in Beryl's death, the young man is understandably devastated, and fearing arrest as what Christie describes as "an accessory before the act," he agrees to let Christie dispose of the body. But when guilt prompts him to go to the police and confess his involvement, he soon finds the finger of guilt for Beryl's murder pointing not at Christie, but at him.

The whole concept of the serial killer is a relatively recent one, the result of improvements in detection techniques and a greater understanding of psychological disorders. Given that many of the most famous serial killers have been American in origin, it is hardly surprising that the serial killer cinematic sub-genre has been largely Hollywood based. Though Michael Mann's Manhunter gradually achieved cult status, it was Jonathan Demme's The Silence of the Lambs that really kicked things off, and if many of the subsequent films have languished in its shadow, we can still be thankful for the likes of David Fincher's Se7en and John McNaughton's Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. The genre's popularity with an adult audience has also seen its scope expand to incorporate female serial killers (a rarity in real life as well as the movies) with Monster, and even spread to the Far East to recreate the pursuit of Korea's first recorded serial killer with Memories of Murder, which paved the way for the dark thrills of films like The Chaser and I Saw the Devil. Russian mass murderer Andrei Chikatilo, meanwhile, became the subject of the too-little seen Citizen X (1995), which is just the sort of compelling and thoughtful work that helped to give the TV movie format a far better name than it once enjoyed. But movie serial killers were around long before the term ‘serial killer' was even first coined.** Try Norman Bates in Pyscho (1960) or even Hans Beckert in M (1931). The concept was even played for laughs as long ago as 1944 in Arsenic and Old Lace, whose multiple murderers are two dotty maiden aunts who kill old men with poisoned elderberry wine and then bury the corpses in the cellar of their house.

Britain, of course, has had its share of real-life serial killers for over a century, and still holds the dubious claim of having the most famous unsolved serial killer case of all in Jack the Ripper. But while the Ripper's anonymity and possible aristocratic connections have always leant the case a sense of perverted glamour, the story of John Christie is anything but glamorous. He is, in essence, the very embodiment of what became so frightening about real world serial killers, that on the surface there is nothing extraordinary about them, nothing to alert even those close to them just what they are capable of. In a memorable Halloween episode of American TV comedy series Roseanne, daughter Darlene is confronted by her mother over her lack of a Halloween costume for the family's trick-or-treat trip around the neighbourhood. "This IS my costume," she informs her. "I'm a serial killer. They look like everyone else."

On paper, at least, Richard Fleischer must have seemed like an odd choice to direct a quietly observed British film about a real-life mass murderer. An American director who once specialised in briskly paced B-movies such as Armoured Car Robbery (1950), The Narrow Margin (1952) and Violent Saturday (1955), he had by this point in his career graduated to larger scale projects like The Vikings (1958) and Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), and had even dabbled with science fiction with Fantastic Voyage (1966) and musical family fare with Doctor Doolittle (1967). But in 1968 he had also made the controversial The Boston Strangler, a dark thriller based on the case of real-life American serial killer Albert DeSalvo, which provided him with credible credentials for the move to Rillington Place.

Fleischer's approach is determinedly low-key from the start, his calmly observant camera and minimalist use of music – even the most dramatic scenes play with almost no musical accompaniment at all – reflecting the drabness of the setting and the surface normalcy of the characters. He never ups the pace to manufacture tension, but then he doesn't need to, as the facts of the case provide the film with all the drama it needs. Instead he quietly watches, like a silent third person in the room who is desperate to either turn away or intervene but unable to do either. Denys Coop's camera rarely moves and when does so it's with a master engineer's precision, and every carefully chosen angle feels designed to economically advance the story or subtly underscore the emotion or subtext of the scene. And while the case has all the makings of a sinister thriller, Fleischer boldly never plays it as one, allowing the horror to emerge organically from the drama, in the process allowing the disturbing banality of this particular backstreet evil to seep slowly into our pores rather than slap us in the face.

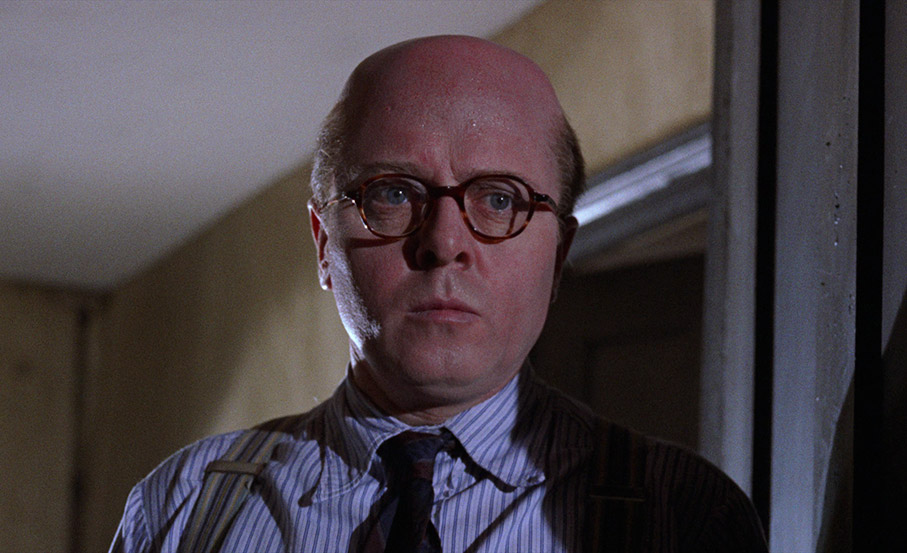

Perhaps Fleischer's greatest asset is his impeccably selected and talented cast. As Christie, Richard Attenborough gives what for me is the finest performance of his career. Delivering almost every line in a soft and somehow suggestive whisper, he transforms a simple glance into an intention to murder and the offer of a cup of tea into a potential death sentence. A quietly terrifying study in creepy malevolence, it's the sort of role for which the actor should be remembered rather than his broader later roles as Father Christmas or the cheery John Hammond of Jurassic Park. Equally impressive is the then young John Hurt as Timothy Evans, here playing his professional victim role to the hilt. With his fantasy-led bragging and sudden but always convincing bursts of anger and explosive despair, he is initially extremely difficult to like, but once he falls victim to the wheels of blinkered injustice, it's nigh-on impossible not to sympathise with his situation and fear for his fate. Also excellent in crucial supporting roles are Judy Geeson and Beryl Evans and Pat Heywood as Christie's wife Ethel – Beryl's terror when she is being gassed by Christie feels painfully real, and the moment when Ethel quietly says to her husband, "I know where you should be" carries with it a wealth of suggestive meaning, and proves a fatal turning point in their relationship.

Fleischer's consistently low-key approach gives rise to some genuinely skin-crawling moments: the appearance in the edge of frame of Christie's hand bearing a cup of tea as a prelude to murder; the extraordinary shot of Christie, his face wild-eyed and grimly determined, pulling on strangely angled ropes as he throttles a woman who is just out of frame; the bone-chillingly realistic discovery of the bodies by a torch-bearing Rudolph Walker (now a regular on Eastenders) that was based on actual crime-scene photos; the soul-freezing look on Christie's face as he eyes the screaming Evans baby, one so weighted with intent that it tells us everything we need to know about his appalling intentions without the need for further elaboration. Later, Fleischer is able to use our memory recall of the tools of Christie's trade to tone things down still further, cutting from Christie's hand holding a rope to him pulling up floorboards, fully aware that the audience can now fill in the narrative gaps.

Working brilliantly both as a dark-toned chiller and a scrupulously researched historical drama (dialogue was drawn from documented sources, sets were based on photographic records and exteriors were shot on location in Rillington Place), the film also delivers as a still pertinent social commentary, reminding us of the horrors of back street abortion (which is once again in danger of becoming a dangerous last resort for desperate women) and pulling no punches in its condemnation of the capital punishment, the monstrous fallibility of which the Evans case still stands as a sobering testament to. Evans' execution is handled with a genuinely horrifying documentary-like realism (the sequence was supervised by real-life crown hangman Albert Pierrepoint, the very man responsible for hanging both Evans and Christie), one whose no-nonsense rapidity so shocked me on my first youthful viewing that I still find hard to watch today. Its impact is heightened by the edit that transports us from the execution back to the title location in what for my money is one of the most jarringly brilliant associative cuts in 20th century cinema.

As a slice of social history, the film is a reminder of how things have changed, but also, sadly, how they have stayed the same. At a time when clear and uncomplicated motives were sought and attributed by unsympathetic and even incompetent investigators (when the police discovered the bodies of Beryl and Geraldine, they were standing just feet from where the other bodies were buried), Evans is convicted in part because no good reason can be offered for Christie's guilt. By not showing the full process of recording his confession (and remember, he had a low IQ, was almost illiterate and was questioned immediately after being told of the death of his child), Fleischer leaves us to ponder on exactly how it was extracted. It may seem unlikely to some that Christie's own wife could remain ignorant of his activities for so long and would keep quiet about them once her suspicions were raised, but just 22 years ago the case of Fred and Rosemary West confirmed that mass murder really can go unnoticed in suburbia for years at a stretch. And lest we mock the medical ignorance of Christie's victims, we should remember that Harold Shipman was able to become the most prolific serial killer in recorded history precisely because of the trust people placed in his status as a medical practitioner.

It was journalist and broadcaster Ludovic Kennedy, in his 1961 book 10 Rillington Place,*** who first brought to the public's attention the gross miscarriage of justice that had resulted in Evans' death, with the very idea that two stranglers could be living in the same house at the same time being just one of 34 unlikely coincidences that he cited in in his case for Evans' innocence. A group of Labour MPs demanded a fresh enquiry into the case be launched, and in 1966 the Brabin Report was published and concluded that Evans probably did not kill his child after all, though it maintained that he had been responsible for the death of his wife. As it was the murder of the child that he had been executed for, Evans received a posthumous pardon. In his book Forty Years of Murder, crown pathologist Keith Simpson maintained that they had hung the right man; the general feeling, however, is that despite the pardon, the British Establishment remains stubbornly reluctant to admit its own appalling failings in this tragic matter.

10 Rillington Place is a masterclass in how to tell a true-life murder story without crass overstatement or sensationalising the crime or its perpetrator. Every aspect of this remarkable film is impeccably handled, from Fleischer's almost invisibly low-key direction to the sublime casting and pitch-perfect performances. The deliberate pace varies little throughout, but the tightness of Clive Exton's screenplay, the economy of the filmmaking and the unsettling sense that Fleischer and his cast really have captured the essence of events as they happened make this consistently compulsive and disturbing viewing.

I always experience a surge of excitement when I see a film that trades on its grittiness and the deliberate drabness of its locations looking and utterly gorgeous as it does on the Blu-ray in Indicator's new dual format release. This 1080p 1.66:1 transfer, sourced from a new 4K restoration by Sony and supervised by Grover Crisp, really showcases Denys Coop's carefully crafted but naturalistic lighting beautifully here. The level of detail that wipes the floor with the previous DVD release, and film's subtle colour palette is handsomely rendered, with rare brighter colours vividly captured (the painted doorways and windows in the Merthyr Vale street in which Evans' aunt and uncle live, the red of Evans' van). The contrast is absolutely spot on throughout, delivering solid blacks but retaining shadow detail (exept where it's designed to), even in darkened interiors at night. The image is spotless, there's no hint of any movement in frame and an organic, fine film grain is visible. Don't use the screen grabs here as a yardstick – our software rendered them darker and more contrasty than they appear on screen.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtracks is consistently clear and without a trace of damage or background his. The slightly narrowed dynamic range and treble bias is par for the course, but it's still better than you'll find many on a good many films of the period.

Optional subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are also available.

Audio Commentary John Hurt

One of three extra features carried over from Sony's earlier DVD release, this really is a treat, with Hurt nicely balancing factual information about the case and recollections of the shoot with anecdotal snippets about the actors, the crew, the studio, the filming of individual scenes and, in one enjoyable side-track, the nature of British censorship at the time. Hurt – whose distinctively throaty voice I could listen to all day – and has strong and positive memories of the filming and some entertaining tales to tell, not least the revelation that real Guinness was used in the pub scene and that multiple takes on this sequence saw him get through about five pints, something he observes just would not happen now due to the "puritanical American influence." A hugely entertaining and informative track.

Audio Commentary Judy Geeson

New to this release is this second commentary track, which easily equals and repeatedly comes close to topping its companion. The first thing to note is that although it's labelled on the menu as a Judy Geeson commentary, Geeson is actually joined by documentary filmmaker and record producer Nick Redman and screenwriter Lem Dobbs, whose credits The Hard Way, Dark City and The Limey and who is clearly a big fan of the film. Redman proves to be an excellent moderator, and both Geeson and Dobbs have plenty to contribute, Geeson from her experience of working on the film and Dobbs from his extensive knowledge of the production and the true-life case on which the film was based. There's just too much here to start listing individual favourites without worrying about missing something out, but Geeson's recollections of the shoot and her approach to playing Beryl are well worth hearing, and there's plenty of praise for Richard Fleischer's direction and interesting discussion on his and John Hurt's film careers. I particularly enjoyed hearing that when something when missing or there was a technical glitch on the shoot itself, the person responsible would always repeat John Hurt's most famous line and claim, "Christie done it!"

Sir Richard Attenborough Introduction (1:29).

In a brief introduction that can be watched before the film itself, Richard Attenborough reveals that this is a film he was proud of, and believes it is important both as a social document and a work of entertainment. This has also been carried over from the earlier DVD release.

Sir Richard Attenborough Interview (22:35)

The always affable Attenborough here covers the process of putting the film together, the involvement of director Richard Fleischer, filming on the actual Rillington Place locations (the street was renamed after the case and pulled down after the filming), and the unified view of those making the film that it should be a cry against capital punishment. Attenborough is a fascinating raconteur, and here comes across almost like an old and knowledgeable uncle reminiscing on a particularly interesting part of his life. Another welcome import from the DVD.

Being Beryl (22:09)

This interview with actress Judy Geeson may seem to be doubling up on the commentary and does have some overlap with stories told there, but there is still more than enough new material to justify its inclusion. It's here, for instance, that I learned there were initially two film versions of the story being proposed, the other (which did not get the green light) to star Paul Schofield as Christie. There are plenty of editing-hiding film clips, but also a couple of stills of Richard Attenborough have his distinctive dome-head makeup applied.

Theatrical Trailer (3:20)

A soberly narrated and unsettling trailer, though I felt for John Hurt, whose introduction consists of, "if ever there was an actor born to step into a dead man's shoes."

Isolated Score

If you're one of those people who question the value of an isolated score, which requires you to sit through sometimes long stretches of silence to get to patches of music, then the one here really will test your patience. John Dankworth's score is certainly effective, but according to Nick Redman on the Judy Geeson commentary there's no more than ten minutes of (non-diegetic) music in the film, which means you'll have to wade through 100 minutes of silence to get to them. Enjoy!

Image Gallery

30 pages of production stills and press materials, which are manually advanced.

Also included with this release is a handsomely produced Booklet, which kicks off with a very fine essay on the film and Fleischer's direction titled The House of Death by Thirza Wakefield, which is followed by a terrific piece in which contemporary newspaper reports on the case have been brought together and commented on. Full credits for the film and a number of stills (including of the actual case and the key participants) are also included.

It's somewhat serendipitous that this new dual format edition of 10 Rillington Place was released just one day before the first episode a new mini-series adaptation of the same story starring Tim Roth and Samantha Morton aired on the BBC. As someone who no longer watches live television, I've yet to see it. I'm in no hurry, as while I'm sure it's very good, Fleischer's film is one of my all-time favourites, and this new dual format from Indicator is the release the film has for so long deserved. A superb transfer is backed by a very fine collection of extras, and this release thus comes with our highest recommendation.

* One of the very few liberties taken with the facts of the case is that in the film Timothy and Beryl's daughter was already born when they first moved in to Rillington Place, whereas in fact Beryl was pregnant and their child was not born until several months later. This change was doubtless made to speed up the timeframe of events without having to resort to "six months later" dissolves or captions.

** FBI Special Agent Robert Ressler is generally credited with first officially defining the concept of what he called a ‘serial killer' in 1974.

*** Clive Exton's script was based primarily on Kennedy's book, and Kennedy himself was technical advisor on the film.

This review has been updated and expanded from our previous DVD review.

|