|

Some years ago I was asked to teach genre to A-level media students on a course where certain elements had already been set before I came on board and were almost a matter of tradition by this point. When it came to picking a specific genre to study, for instance, I was given two choices – westerns or horror movies. Both had their advantages. A key plus of the western is that its codes, conventions and iconography are so instantly recognisable – show anyone a promotional still from almost any western and they instantly know in which genre the film belongs. Horror, on the other hand, was and still is an absolute goldmine for socio-political subtext, a feature that is not so prominent in westerns, though there are a select few that that seem to invite you to look beneath the surface for secondary meaning. Just occasionally that subtext would be sharply defined enough to raise a few hackles. I'll be coming back to this a little later in this review.

The 1952 High Noon, written by Carl Foreman and directed by Fred Zinnemann, is on the surface a film of bewitching purity, beneath which sits a work of captivating structural and thematic complexity. That surface minimalism is signalled up front by a title that consists of two single-syllable words, which used together once denoted what we now call midday, and in common with a number of celebrated westerns, it gives no indication of the genre or subject matter. This uncluttered simplicity is carried over into a story that can be easily summed up in a single sentence: a vengeful killer is released from prison and, together with three associates, heads back to the town of his capture to kill its newly married marshal, who delays his retirement to confront the man and his gang, but is forced to do so alone when none of the once supportive citizens is willing to offer their help. There is, of course, so much more to it than that, and this really is a film in which the devil is in the detail.

Right from the off there are ways in which High Noon breaks with genre convention, at least as it stood in the early 1950s. First, at a time when colour was becoming a genre standard, it's in black-and-white, a pared-down palette that acts as a visual reflection of the film's fat-free storytelling, which is emphasised further by intentionally undramatic lighting and blankly cloudless skies. Next, instead of opening with the splash of the main title and a loud orchestral cue, it begins with a wide shot of a lone cowboy sitting contemplatively in a landscape that he almost seems to have become part of, the scene gently underscored by a musical pulse beat. This is Jack Colby, played wordlessly here in his first screen role by later genre star Lee Van Cleef. It's only as Colby gets up to keenly observe the approach of a second figure that the titles begin and that opening pulse breaks into The Ballad of High Noon, a song more commonly known as Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling. Sung by Tex Ritter,* it's not your typical western opener, a mournful piece whose lyrics effectively outline what is soon to play out and encapsulate some of the film's themes. As the titles and the song unfold, Colby meets up with comrades Jim Pierce (Robert Wilke) and Ben Miller (Sheb Wooley), and the three head towards the town of Hadleyville like three horseman of the apocalypse to await the arrival of a fourth in the shape of Ben's Brother Frank, who has been recently pardoned for murder and is due on the noon train.

As the three bandits ride slowly through town, the reactions they prompt from those who see them tell us all we need to know about these men. One man stands up in his carriage and looks at them in shock, an old woman crosses herself, and a fireman stops polishing his vehicle and rushes inside. As they ride past a group of men gathered outside a saloon, the film's first words of dialogue are spoken, and even then they don't really count as exposition. When the men pause briefly and purposefully outside of the currently vacant Marshal's office, we learn that they're not in any hurry to conclude their business, whatever it may be. Then, in the first of a whole string of extraordinary shots you'll find in the film, we watch the three men from the inside of a building as they trot past a window, only for the camera to pull rapidly back and Judge Percy Mettrick (Otto Kruger) to step into shot with a magician's timing to begin the officiation of Marshal Will Kane's marriage to what looks like his granddaughter. Sorry, I'm being a tad sarcastic there and perhaps unfairly so, given how common it was in Hollywood movies of years past to feature couples where the man is clearly two or three decades older than his female partner. What's interesting here is that the thirty years that very visibly separate Kane from his new wife Amy (played by the 21-year-old Grace Kelly in her feature debut) is partially balanced by what most seem to agree was intended to play as a second age-gap relationship between Mexican businesswoman Helen Ramírez (a bewitching Katy Jurado) and Kane's Deputy, Harvey Pell (Lloyd Bridges). Here we are encouraged to believe that Harvey is Helen's junior by several years, despite the fact that Bridges was actually 11 years older than Jurado. Yet he's definitely cast as Helen's toy boy, a likeable and doubtless virile young man whom Kane is happy to see wearing the deputy's badge but whom he believes is still too immature to be marshal.

If you come to the film for the first time knowing only the outline of the plot, then the first few minutes following the arrival of a fateful telegram informing Kane that Miller has been paroled might seem to bring the story to a premature close. By the time Kane learns that Miller has been set free and will be arriving on the noon train, he has married his new bride, hung up his guns and turned in his badge. And despite his concerns and the fact that the replacement marshal will not arrive until the following day, the townsfolk cheerfully bundle Kane and Amy into their carriage and send them on their way with the assurance that they'll take care of Miller when he shows his face. Well, that's it then. Roll the credits. Of course, it can't end there, and as Kane and Amy ride off towards their new home, wherever it may be, the torment of Kane's decision becomes increasingly visible on his face, and he eventually turns the carriage round and heads back to town. The good citizens seemed ready to deal with Miller without him, so they'll doubtless rally round now that he has returned. Won't they? It's worth noting that Kane's chosen course of action is subtly signposted by a notice visible on the wall behind him when he opens the telegram, a poster that refers to world events and proclaims, "War is Declared!" before expressing the urgent need for volunteers. There's a lot of subtle and smartly thought-out signposting in this film, much of which requires a second or third viewing to even pick up on.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the first person to turn her back on Kane is Amy, who as a pacifistic Quaker is opposed to violence of any kind and is indignant at Kane for being so willing to put himself at risk for what she believes is no longer his responsibility. She tries reasoning and even pleading with him and is unshaken by his logical claim that if Miller wants to kill him then he and his boys will likely follow them if they choose to run, and then they'd be alone on the prairie and unable to call on the good people of Hadleyville for help. Helen then delivers what feels like a most unreasonable ultimatum for a newly married woman who claims to love her man, that he leave town with her now or she'll depart without him on the very train on which Miller is due to arrive. Once again that Declaration of War sits behind them as their potential break-up imbues it with a third layer of meaning. Do not forsake me oh my darling...

Next to depart is Judge Percy Mettrick (Otto Kruger), the Justice of the Peace who married Kane and Amy just minutes earlier but who Kane finds hurriedly packing his worldly goods into saddlebags and in a very big hurry to leave town. He, it is revealed, is the one who passed sentence on Miller at his trial and thus also expects to be a target of his wrath. Like Amy, he encourages Kane to follow his example and hit the road. I'll be coming back to him, as his departure has relevance to the film's socio-political subtext.

With just an hour to go until the train arrives, Kane begins the task of trying to recruit deputies and soon discovers that the citizens' earlier (and, as it turns out, deceptive) confidence that they could handle Miller has since drastically waned. Almost everyone he talks to has a personal reason for declining his request for assistance, with each encounter exposing the worst fears of the person in question. Harvey seems willing to help but is put out by Kane's lack of faith in his ability to take on the role of marshal, and after an unimpressed Helen throws him out, he storms off to the saloon to drown his hurt pride in a bottle of whiskey. Former marshal Martin Howe (a quietly excellent Lon Chaney Jr.) reminds Kane, in a single economically written line of dialogue, that his knuckles are busted and riddled with arthritis and thus reasons that he'd be more of a hindrance than a help. Herb Baker (James Millican), a member of the posse that helped capture Miller in the first place, seems up for the job, but when Kane later reveals that it's down to just the two of them, his nerve fails him and he stumbles with excuses until Kane cuts him loose and tells him to go home. His friend Sam Fuller (played by Harry Morgan, and yes you read that character name right) doesn't even have the nerve to face Kane with whatever excuse he might be able to concoct, and instead sends his wife to the door to tell the marshal an awkward lie about his whereabouts while he sits frightened and shameful in the living room. On the rare cases when help is offered, Kane has little option but to turn it down, giving drink money instead to one-eyed alcoholic Jimmy (William Newell) and rejecting the enthusiastic pleas of 14-year-old Johnny (Ralph Reed), despite his quiet admiration for the boy's pluck. Later, when Kane appears to have lost respect for almost everyone in the town, he makes a small but deeply meaningful exception for a boy he clearly sees has a future ahead of him, one he was able to protect by his decision.

Twice Kane makes his case to groups of local people at diametrically different public locations. At the church, in a scene that was directly parodied by Mel Brooks in Blazing Saddles and hints at Carl Foreman's disdain for religion, Kane's request triggers a heated debate in which arguments for and against helping him are thrashed out, with the communal decision not to do so shaped primarily by the triple corruptors of politics, economics and self-interest. At the saloon, he is given a discomforting reminder that Miller still has friends here and that not everyone was happy about his arrest. Again economics play a corrupting role here, summed up by an oily hotel clerk (Howland Chamberlain), who admits to the waiting Amy that he dislikes Kane because business was much better when Frank Miller was around.

Every bit as important as what is said and done here is what is inferred. We learn early on that before he met and fell for Amy, Kane was in a relationship with Helen, and it's clear that while she still has feelings for him, she also harbours some resentment over a breakup that was likely initiated by Kane. It's an emotional self-conflict that is first indicated by a simple movement of Helen's body – when her associate Sam (Tom London) asks her if she wants him to see if he can help Kane, she leans forward just enough to reveal her longing for an offer that she then gives some thought to and ultimately turns down. That Helen's initial instinct is communicated so effectively is all the more impressive when you consider that when she makes this small move she has her back to the camera. Later she talks to Amy, who at this point has just become aware that Helen and Kane were once an item, and it becomes clear that Helen has a far better understanding of him than Amy does, which made me wonder just how long Kane and Helen have known each other and indeed how two such seemingly mis-matched individuals could have met and fallen in love in the first place.

Helen's lingering affection for Kane does not stop her from making immediate plans to leave town on the same train as Amy. It's never revealed exactly what crimes Frank Miller committed, but we know from every mention of his misdeeds that they were bad, something first implied when Mettrick says to Kane, "Have you forgotten what he is, what he's done to people?" We also learn that before she got together with Kane, Helen was Miller's girl, and both we and she can assume that he is likely to want to make her pay for subsequently taking up with his mortal enemy. As a character, Helen is fascinating, and another component of the film that breaks with genre convention, a smart and elegant Mexican woman who has bankrolled and remained a silent partner in a number of the town's businesses, including a store run by Ed Weaver (Cliff Clark), a middle-aged white male who clearly respects Helen and who is treated fairly by her when she offers to sell her share to him. As Meir Ribalow notes in the special features, it's actually hard to see why Kane would chose the innocent and moralistic Amy over the smart, level-headed and frankly lovely Helen, particularly when she and he appear to be so in sync. As it happens, the explanation he offers makes sense for a man looking to put his past behind him and start a new life free of conflict and violence – I just can't imagine life with Amy could be anywhere near as much fun as even a few weeks in Helen's company.

Technically, the film is close to flawless, inspired in its audio-visual approach to storytelling, immaculate in its pacing, and brilliantly shot by cinematographer Floyd Crosby, who makes striking use of the Academy ratio and whose sometimes extraordinary deep focus work gives Greg Toland's celebrated compositions in Citizen Kane a run for their money. He also pulls off one of film history's most celebrated crane shots, as the camera pulls up and out from a mid-shot of Kane to an extreme wide of the town's now empty main street in one of cinema's most perfectly realised expressions of loneliness, isolation and fearful abandonment. Elsewhere, sometimes motion-free shots prove more expressive than dialogue or action (Miller's arrival is repeatedly anticipated by a static shot of train tracks that seem to taper off into infinity), which peak in a brilliantly realised montage as the town's clocks tick down to noon. It's one in which Crosby's compositions, Dimitri Tiomkin's music and Elmo Williams' consistently superb editing combine to genuinely pulse-raising effect, building to a crescendo that is punctured by what may be the western genre's most portentous train whistle. Years later, much was made of 24's real-time storytelling and use of a countdown clock, but almost 50 years earlier both were every bit as crucial to the manner in which High Noon unfolds. The clocks may be analogue here, their ticks and pendulum swings providing the heartbeat drive for Tiomkin's extraordinary score, but by making them a crucial aspect of the film's mise en scène, the speed with which the fateful hour is bearing down upon Kane is every bit as evident and urgent to him as it becomes to the audience.

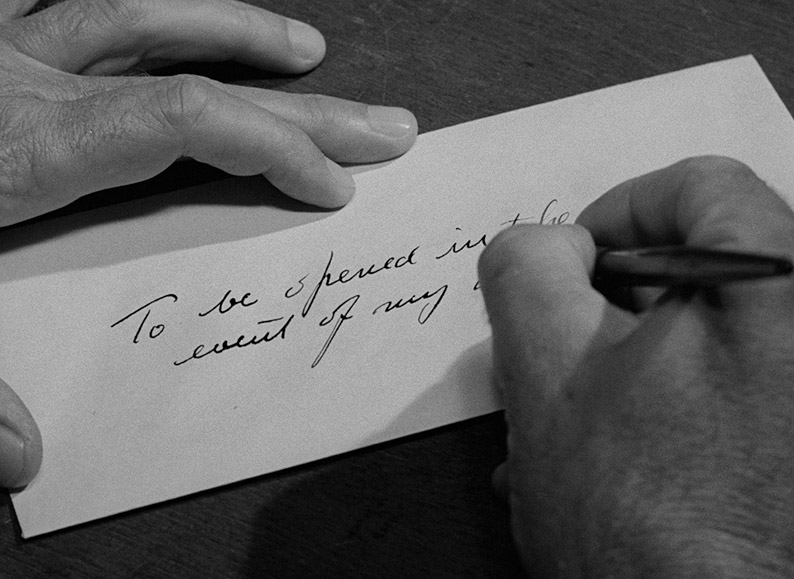

Although now widely recognised as a genre classic, opinion was a lot more divided on its release. As a western, High Noon breaks so many of the genre's established rules that it was disliked by some genre purists, but the nostrils it really burrowed into were those of Hollywood right-wingers. First up, they objected to a central character who was an ordinary man with everyday weaknesses instead of a fearless and sharpshooting superhero. In traditional westerns the good guys went up against the villains and showed no fear, and if the odds were stacked against them then that didn't matter, they were crack shots and could always call on the assistance of a number of similarly skilled comrades. The very idea that a western movie marshal could fear for his life, write his last will and testament before heading into battle, and even break down in tears at the prospect of his seemingly inevitable death was an anathema to them. Real men don't feel fear, real men don't cry, and real men stand in the street and simply outdraw the bad guys, they don't hide and fight using hit-and-run tactics. And the suggestion that good American townspeople could ever be so cowardly that they would be willing to watch a good man die rather than put their own lives at risk was, in their view, a preposterous one.

All of which, of course, is complete and utter bollocks. One of the things that continues to make High Noon such a crucial western is that it dispensed with the genre's fantasy heroics and grounded its characters and story in reality. In the real world, only a sociopath would really not care if he or she lived or died, and Kane's tears are born as much from his frustration, despair and sense of abandonment as they are from his conviction that he is to die a senseless death on what should have been the first day of a new life with a woman he loves. The reluctance of the citizens of Hadleyville to help him also has its basis in a societal truth that was still being explored by American cinema almost two decades later in films like The Incident, in which the passengers in a subway train carriage are terrorised by two thugs whose reign of terror is able to continue because none of the other passengers have the confidence to forcefully intervene. It's a similar story with this film's climactic confrontation (skip to the next paragraph to avoid spoilers, where you'll be warned to do likewise before that paragraph ends), which genre traditionalists would have preferred to see staged as a stand-up, one-on-four gunfight in Main Street. Instead the battle unfolds far more plausibly, with Kane employing guerrilla tactics to pick off Miller's men one-by-one, given timely assistance at one point when a transformed Amy shoots one of them in the back as he reloads. Shot in the back by a woman. I'll bet that went down a storm with the traditionalists.

Of course, there's plenty more to rattle right-wing genre purists here than a sensitive marshal, small town cowardice and duck-and-dive fighting tactics. High Noon was written when the House of Un-American Activities was busying its wretched self by purging Hollywood of anyone and everyone who had ever held progressive political beliefs. It was, as I said in my review of The Front, a dark time for American society and American cinema, one that destroyed lives and the careers of great and talented people and even forced some of them to flee the country. Foreman, himself a left-wing progressive, was enraged by what was happening to people he knew and respected, and saw here an opportunity to weave a commentary on this right-wing persecution of the creative community into his screenplay. Thus, while on the surface High Noon is a western about a principled man doing what a man has to do against difficult odds, it also plays as an allegory of McCarthyite America, one in which Hadleyville is Hollywood, a happy and productive place until the arrival of the vindictive House of Un-American Activities in the shape of the Miller gang. The members of this community initially respond with dismissive confidence, but when one of their number is targeted they quickly turn their backs on him, just as so many did in Hollywood when faced with the career and reputation-wrecking prospect of being tarred with the same brush through association. Long-standing friendships and working relationships were destroyed overnight, as individuals named names to project their own careers and others disassociated themselves from the accused to avoid also becoming the target of vindictive persecution. Viewed in this context, the actions of the townspeople are believable because they were an accurate reflection of the behaviour of those who had chosen to shun their former friends and colleagues in the blacklisted America of the day. And in a case of life imitating art, during the course of the film's production Foreman was also hauled before the Committee, and like the Marshal Kane of his creation he refused to buckle under and name names. As a result, he was stripped of his co-producer credit on the film and demands were made that his name be removed as author of the screenplay as well – only the defiant stance taken by his good friend Gary Cooper, a lifelong Republican who did not hold with the Committee's actions, prevented this further act of ignominy. In a final unfortunate parallel (once again, hop to the next paragraph to avoid spoilers), the ending of the film – which sees Kane contemptuously tossing his marshal's badge to the ground at the feet of the citizens who turned their back on him and then riding out of town – almost plays as a prediction of Foreman's own departure from America to Britain when further job opportunities in Hollywood all disappeared.

It's been noted that director Fred Zinnemann did not see the story in quite the same light as Foreman, but as a socially conscious Austrian Jew who spent his formative years in pre-WW2 Germany, he clearly responded to the themes of social isolation and prejudice and the conviction to do what you believe is right whatever the consequences. In remaining faithful to Foreman's screenplay, he also gave visual realisation to some of his intended themes. Nowhere is this more evident than in the scene where Kane discovers Judge Mettrick packing up his belonging in preparation for his hasty departure, where the first things the man who is an emblem of the rule of law takes down and puts away are an American flag – ostensibly a symbol of the country and its values – and the scales of justice. How's that for symbolism? Later, as Kane walks the street alone, two anonymous citizens scurry away at his approach rather than converse with him, an experience that would be painfully familiar to those who found themselves unjustly blacklisted as a result of the Committee's actions.

If it seems I've got a little carried away analysing a film that is ostensibly a straightforward tale of a man doing what a man has to do, it's because there's just so much material here to sink your deconstructive teeth into. It's the very fact that it works so well on so many levels – technically, artistically, subtextually, allegorically, and as a masterful example of film storytelling – that makes High Noon such a giant in a genre that has more than its share of tall-walking works. It's a film whose every component is exceptional, and it seems only appropriate that a work in which clocks play such an important and iconic role should be as finely made and tuned as a proverbial Swiss watch.

| sound and vision – blu-ray |

|

Sourced from a 4K digital restoration, the 1.37:1 1080p transfer on the Eureka Masters of Cinema Blu-ray is terrific. The detail is consistently crisp, any blemishes or damage have been cleaned up or repaired, and the monochrome tonal range is consistently lovely, ensuring the black levels are solid, the highlights are stable and the grayscale between is handsomely rendered. A fine film grain is visible and the image is consistently stable, with no errant jitter.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack is clear, albeit with the expected restrictions in the dynamic range, which gives the soundtrack a slight treble bias but not so that it adds hiss to words ending in the letter ‘s'. The music fares particularly well here.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

One of the initially unforeseen problems of reviewing disc releases over the course of 20+ years is that the format has twice undergone quite significant evolutions. Those with long memories will remember that Cine Outsider began life as DVD Outsider, a name chosen because of the quantum leap DVDs represented over the VHS tapes and SD broadcasts of previous years. How could they top this for image quality, we once wondered? Years later, standard definition had been left in the dust and TVs were moving to 2K HD and growing in size, with the 16:9 widescreen now replacing the 4:3 aspect ratio that we had long since previously accepted as standard. Then along came Blu-ray, after winning the HD format war with HD-DVD, to raise the bar for potential excellence when it came to transfer quality, having a far higher resolution that DVD and with the picture made up of pixels rather than interlaced lines. Then along came even larger 4K televisions, and a new disc format was born in the shape of Ultra High Definition Blu-ray, or UHD. This represented another substantial jump in image resolution, but with the added advantage that it could support High Dynamic Range, or HDR, allowing for a wider contrast range and more precise and expansive colour definition than Blu-ray.

Which brings me to the new Eureka UHD release of High Noon, which was, as far as I’m aware, sourced from the same 4K restoration as the 2019 Blu-ray release. I highly praised the transfer quality on the Blu-ray at the time with good reason, but as I noted in the preceding paragraph, UHD and the increased screen size of many 4K televisions (mine included) has set a new standard for image quality excellence, one that admittedly is not always met by the transfers in question. So does this new 4K transfer improve on the already strong one on the previous Blu-ray? Oh yes. As you would hope, the increased definition of UHD results in even crisper and more clearly defined detail than the Blu-ray, something especially evident of close-ups of faces (and there are plenty of those here) and textured elements such as clothing or wooden and metal surfaces. This also results in a more visible grain, though it remains unobtrusive and pleasingly organic to the film image. Stood side-by-side with the Blu-ray, the 4K image is also noticeably brighter, with the Dolby Vision HDR bringing out a lot more detail in the darker areas without ever blowing out the whites or other highlights. Thus, while I stick by my original assessment of the Blu-ray transfer, I’ll freely admit that it’s been visibly surpassed by the Dolby Vision enabled 4K transfer on this new UHD.

Due to the film’s age, the Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack does not differ significantly from the one on the Blu-ray, and I’ve no complaints there.

Once again, the disc includes optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired.

Audio Commentary by Historian Glenn Frankel

I do like audio commentaries, but for me this one is a bit of a mixed bag. As you would hope from the author of High Noon, The Hollywood Blacklist and The Making of an American Classic, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Glenn Frankel provides some detailed information on Carl Foreman's dealings with the House of Un-American Activities Committee and how his views on these proceedings are allegorically reflected in the film. This is good stuff. Unfortunately, and as ever I'm speaking from a personal viewpoint here, he spends way too much of the time simply describing what's happening on screen, with the result that much of the commentary plays almost like an audio descriptive track.

Audio Commentary by Western Authority Stephen Prince

Western authority Stephen Prince Gives us a lot more to chew on in this second commentary, though I still managed to get unreasonably irked by the fact that he highlights so many of the things I'd covered in my review, once again making it look as if I'd just lifted it from him. Then again, the points in question should be self-evident to anyone taking a good look at the film, so this gripe is effectively moot. This really is an informative extra, with Prince discussing the locations, the actors, the editing, the symbolism, the characters, the themes, the blocking of actors, the use of deep focus photography, the in-film relationships, the subtext and a whole lot more. He recognises that Rio Bravo was made by Hawks and Wayne as a direct response to what they disliked about High Noon, then makes a solid case for why he believes High Noon is the better film, and ends with the veiled suggestion that its commentary on American society has found new relevance of late. I wonder to whom he was slyly referring?

Women of the West: A Feminist Approach to ‘High Noon’ (18:15) – UHD only

The only special feature new to the UHD release is this video essay by J. E. Smyth, and it’s a compelling inclusion that convinced me that I had failed to fully acknowledge the strength and key role in the narrative of the two lead female characters, as well as how this challenged the genre conventions of the day. Smyth is persuasive in her arguments, noting that how rare it still is to see an authoritative Mexican-American businesswoman like Helen in a western, and comparing Amy’s proactive role in the final stand-off between Will and Frank Miller with the more passive one played by Holly in the similar confrontation at the climax of the 1988 Die Hard. She cites a range of sometimes eye-opening historical facts to make a case for the authenticity of the strong-willed female characters, suggests that the good-looking Cooper is in some ways cast as the damsel in distress for Amy to rescue, and states that “High Noon wasn’t just remarkable for its era for presenting empowered articulate female protagonists of any race or ethnicity, it’s remarkable in any era.”

Interview with Neil Sinyard (29:35)

The ever-knowledgeable Mr. Sinyard takes a detailed look at what makes High Noon so special in a genre that has its fair share of enduring classics. He touches on the various themes and socio-political readings of the film, the pared-down and newsreel-influenced visual style, what he describes as "Zinnemann's three visual strategies," the myth that the film was somehow rescued in the editing, the strong female characters, the score, and more. He also talks about the film's long-term impact, and there's even a poster included here (which I'd never seen before) for Solidarity, the Polish trade union movement of the 1980s, that features Gary Cooper's Kane as a symbol of the union's struggle and resistance to government repression (this is also in the booklet, I should note).

Carl Foreman Interview (76:43)

Recorded at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank) in 1969, this on-stage Q&A with screenwriter Carl Foreman is a hugely valuable inclusion. Introduced at some considerable length by a gentleman whose full name I didn't catch, Foreman answers questions from the audience with grace and honesty on a variety of topics. These include the difference between writing in America and the UK, his first experience in the director's chair on The Victors, working with his producing partner Stanley Kramer, the experience of making High Noon and its life-changing aftermath, how the messages in his films have sometimes been misinterpreted, his planned future projects (one of which, Young Winston, is coming to Blu-ray soon from Indicator), the importance of holding a mirror up to contemporary life, and more. He salutes the emergence of great new British writers, expresses a hope that there would one day be a National Film School in Britain (such an establishment was founded just two years later), and cheered me with his open disdain for religion and his dismissal of "the spirit of Christmas" as "a load of crap." There are some audio quality issues in places but they're easy to live with given the quality of the content.

Inside High Noon (50:00)

A 2006 documentary on the film from director John Mulholland that covers that by this point – assuming that you're watching the extras in order, of course – should be largely familiar ground, but does so by talking not just to film theorists and writers, but to the offspring of some of the film's key contributors. These include Gary Cooper's daughter Maria, Carl Foreman's son Jonathan, Fred Zinnemann's son Tim, and Grace Kelly's son, Prince Albert of Monaco. Being so close to their parents, and in at least one case having visited the set during the film's making, their words have authority, particularly when Jonathan Foreman states categorically that the film was indeed intended as a comment on the blacklist, to which his father fell victim even before the production was completed. There's a comprehensive look at how the film came about and was made, information on missing subplots, and some learned opinion on the strength and importance two main female characters. There's some detail on the blacklisting of Foreman and how Gary Cooper put his career on the line to defend him at every turn. Former US President Bill Clinton even chips in to rather eloquently outline why one of his favourite films is so popular with politicians, and we get a peek at Zinnemann's annotated shooting script (which the director sent to Clinton) and a letter in which he counters the myth that the film was saved in editing. There's much more here, including some very thoughtful analysis of the film's visual style, themes and subtext.

The Making of High Noon (22:11)

A 4:3-framed archive piece from 1992, hosted by an ever-smiling Leonard Maltin, that looks back at the making of an unconventional western classic. A solid and detailed piece, it includes interviews with producer Stanley Kramer, director Fred Zinnemann, Floyd Crosby's son David (yes, the famed musician), actor Lloyd Bridges, and Tex Ritter's son John, who reveals that singing the theme song at the Oscars (where it won Best Song) was the highlight of his father's career. Many of the stories here are repeated elsewhere, but this still makes for a comprehensive introduction to the film and doesn't sidestep the controversies surrounding its release and the damaging effect of the blacklist. "Evil was very strong in those days," notes Bridges with feeling.

Behind High Noon (9:48)

A 2002 piece made as a 50th anniversary tribute to the film, directed by John Mulholland and constructed from the same interview material used for his 2006 documentary Inside High Noon, also included on this disc. Now when I say the same material, I don't just mean that the clips used here were sourced from the same interviews, but that much of what you'll see here is also in that documentary, and if you're watching the extras in order you'll already have seen most of this before. What is unique to this piece is a to-camera introduction and narration by Maria Cooper, and there are a few snippets of previously unseen interview footage.

Trailer (2:17)

"A man who was too proud to run!" is the misleading claim that heads up this so-so trailer, which, in that still-annoying need to pack such a preview with action, has some big spoilers for the film's climactic confrontation. It also informs us that "Time was his deadly enemy!" No, I think that was Frank Miller.

Booklet

Running a substantial 100-pages, this is a hell of a booklet even by even by Eureka's always high standards. Leading the pack here is a belter in the shape of the whole of The Tin Star by John W. Cunningham. Although credited on the film as the magazine story on which the film was based, the special features reveal that Carl Foreman was already writing the screenplay when he was made aware of the existence of Cunningham's story and the similarities it bore to the script he was writing, and the production company brought the rights to the story to avoid any potential copyright issues. There are as many differences between the two works as there are similarities, and it's clear that having got his hands on it, Foreman drew on Cunningham for some of the details in his own script, from an arthritic hand that afflicts the lead character in the original (and the former marshal in the film) to the names given to two of the Miller gang members. To have the whole story for comparison rather than just a few choice extracts is a serious plus. This is followed by a detailed new essay on the film by Philip Kemp, one that includes details about its making that I hadn't picked up in the previous extras and is a damned fine read. Next is a retrospective review of the film by Richard Combs that was first published in the June 1986 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin and it makes for fascinating reading – indeed, so thoughtful and well researched and argued are Combs' points that I was struck by feelings of woeful inadequacy for my own paltry efforts. Also by Combs from 1986 is a critical breakdown of the film's real-time storytelling and its use of clocks, and unless you've seen and studied the film in detail numerous times, you're likely to learn something here. Finally, we have a rather wonderful piece by Carl Foreman about his tempestuous relationship with famed High Noon hater John Wayne, one written in 1974 and published in the satirical British Punch Magazine. The booklet is handsomely illustrated with posters, promotional still and behind-the-scenes photos, and as ever includes the main credits for the film.

As a long-standing fan of westerns I've always had a lot of time for High Noon, but only coming back to it after a gap of many years was I able to appreciate just how superb a work of American cinema it truly is. The filmmaking is inspired, the script precise, the acting top-notch, the storytelling taught and waste-free, and the socio-political undertones give it a bite that few other genre works of the period can boast. It's a marvellous work, and great though it was to see it looking as good as it does on this impeccable Masters of Cinema Blu-ray, the new UHD looks even better and has the added bonus of the thoughtful J. E. Smyth video essay. Great film, great presentation, superb special features... whichever format you prefer, both get our highest recommendation, but the UHD definitely has a serious edge here.

|