|

A year or so ago, after one of our intermittent High 5 postings, Camus and I briefly toyed with the idea of compiling a short list of what we deemed to be perfect movies. Like all such lists, it would be a completely subjective call, but we both had specific titles in mind when the idea was floated. And such films are rare indeed. We can all reel off a list of favourite films, but how many of them are so perfect in our eyes that there is nothing about them we could criticise or would think of changing just one iota? For reasons I can't recall, this particular High 5 never came to be. But even as I was pondering on what titles to include on mine, I was planning a follow-up, a list of film roles in which the casting was so perfect and where the actor got so completely inside the mind and body of their character that you genuinely forgot you were watching a performance and had to take a few steps back on subsequent viewings to fully appreciate their skill in making it happen. This, of course, also failed to materialise as a High 5 piece, but as soon as the idea came to me, the first name that went onto my list was Edward Fox in The Day of the Jackal.

But I'm getting ahead of myself here. The Day of the Jackal, a 1973 Fred Zinnemann-directed adaptation of Frederick Forsyth's first novel, opens in Paris in 1962 as members of the OAS (Organisation armée secrete, or Secret Army Organisation), a right-wing paramilitary group fiercely opposed to Algerian independence, launch a failed attempt to assassinate President Charles De Gaulle by ambushing his motorcade. When the operation's organiser, Jean Bastien-Thiry, is caught and executed, the remaining heads of the OAS go into exile, and with De Gaulle's already enviable security now tighter than ever and their own organisation riddled with leaks, they elect to hire an outsider to assassinate De Gaulle, selecting an Englishman with an enviable record who elects to work under the codename, 'Jackal'. He commands a sizeable fee for what he points out is a once-in-a-lifetime job, which OAS operatives raise through a string of bank robberies, actions that police and government officials quickly realise have an ulterior motive. It is reasoned that a further attempt on De Gaulle's life is being set up, and put in charge of uncovering whatever the plan might be is Deputy Chief Commissioner Claude Lebel. The monumental difficulty of the task is concisely laid out by his immediate superior Commissioner Berthier:

"We're in trouble on this one. Our agents inside the OAS can't pin him down, since not even the OAS knows who he is. Action Service can't destroy him; they don't know who to destroy. Territorial Surveillance can't pick him up at the border because they don't know what he looks like. The gendarmes, all forty-eight thousand of them, can't pursue him; they don't know who to pursue. And the police can't arrest him. How can we? We don't know who to arrest."

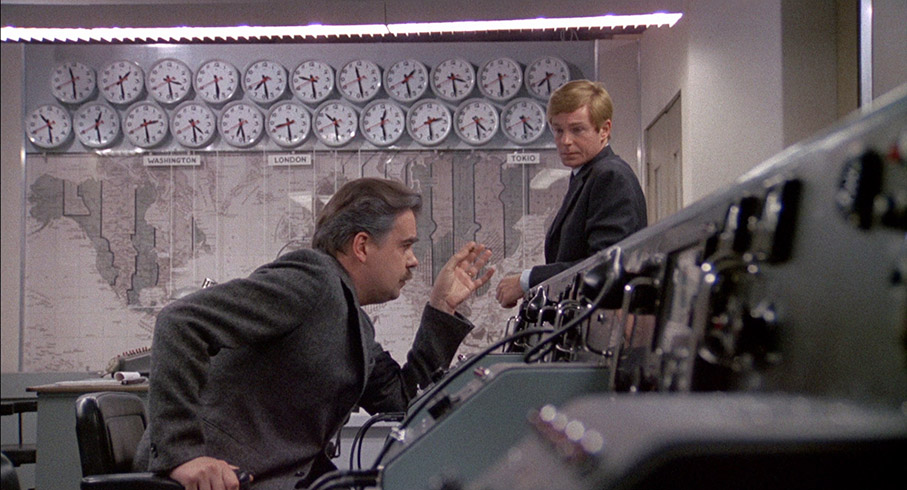

Lebel is required to submit a verbal report each day to of a group of government and security officials. Unbeknown to any of them, one of their number has been targeted by a female OAS agent, with whom he begins an affair and who feeds back everything that the police uncover directly to her colleagues. The OAS leaders, meanwhile, are holed up in a protected top floor apartment in Rome, and even they do not know the Jackal's location or timetable. As the Jackal makes his preparations and Lebel continues his investigation, an urgent game of cat and mouse begins.

Stories of men (it's almost always men) in positions of power who are targeted for assassination and the race to uncover the plot to kill them are not exactly rare. Where both Forsyth's novel and Zinnemann's film depart from the fictional norm is that the setup to their story has a basis in historical fact. De Gaulle was the target of a number of OAS assassination attempts, including the very one that opens this film, which was indeed organised by one Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry, who was later caught and executed by firing squad. While this does quickly give the film a grounding in reality, it also has the potential to work against it, as anyone with even a passing knowledge of modern French history will be aware that De Gaulle was not assassinated and died in 1970 of natural causes, which can't help but suggest that Jackal's plan is doomed to fail from the start. Yet as with Alan J. Pakula's All the President's Men, which revolves around the uncovering of one of the most famous scandals in American political history, the tale here is told with such skill that the ending never feels like a foregone conclusion, and the fascination comes from the consecutively unfolding processes of preparation and investigation. Intriguingly, it's a journey that divides our loyalties. Where many such tales sit firmly on the side of the investigating agents and paint the assassin as someone that a reasonable viewer would want to see stopped at any cost, here the Jackal is presented as a smart, resourceful and charismatic professional, and his complex preparations for a plan that even we are only privy to as each stage of as it unfolds is one of the most compelling aspects of the film.

As a result, even though it's easy to sympathise with the likeable and put-upon Lebel and quietly cheer for his hard-won breakthroughs, it's the Jackal that I find myself consistently rooting for. There are solid reasons for this. Firstly, we get to meet him and follow his progress some time before Lebel even enters the story, by when we already have some investment in him as the film's central character. It's also easy to warm to his position as an individual taking on the might of the system against seemingly impossible odds – a system that is prepared to torture an OAS operative to death to get information – and to be impressed by his daring and ingenuity. But key to the bond we form so quickly with the Jackal is the captivating nature of the man himself. Which brings me back to Edward Fox. So sublimely does Fox inhabit the role that the very idea that actors such as Michael Caine, Robert Redford and even Roger Moore (seriously?) were once considered for the part now seems preposterous. Zinnemann wisely held out for an actor who would not then have been instantly recognisable and absolutely struck gold with Fox. From the moment he first exits the flight that delivers him to the exiled OAS leaders, Fox wears his character like a second skin. It's evident in everything he says and does and even his body language, from his always purposeful stride to the confident but never overly suspicious way that he sizes up locations and the people around him, quietly evaluating everything that might be useful to him or even pose a threat, but wrapped in the smart-casual clothing and easy-going smile of an appreciative tourist. That he's not to be messed with is established early on when he dispatches a would-be blackmailer with just two sharply delivered blows, and the sheer confidence with which he executes every step of his ingenious plan casts him a very real force to be reckoned with.

Fox also peppers his performance with small details that add to the feeling that he fully understands the thinking behind everything he does, even if we initially do not. It's something that particularly struck me when he sneaks into the office of an elderly concierge to press a room key into moulding compound from which the copy will be later cast. It's an action we've certainly seen before in crime and caper movies, but before pressing the key into the compound here, Fox rubs it against his chin. On my first viewing I was both bemused and intrigued by this little bit of business, and only later reasoned that he does this to add a fine layer of oil – or whatever equivalent it is that we secrete from our skin – to prevent the key from sticking to the compound and distorting the impression. Why does he use his chin? I genuinely don't know, but from the almost regimented manner in which this action is executed, it's clear that the Jackal does know, and that's all that matters. Not only does this suggest that he's a past master of this, but also that he knows more about copying keys than we thought we knew from watching other (lesser) movies. There are many such small details, all of them noteworthy and all contributing to the appeal and mystique of the character. I really could watch The Day of the Jackal over and over again just to watch Fox at work and get something new from his performance every time.

But he's not alone here. Despite the French setting, Zinnemann litters the supporting cast with stellar British acting talent of the day, including Timothy West as Commissioner Berthier, Derek Jacobi as Lebel's assistant Caron, Maurice Denham as General Colbert, Eric Porter as OAS leader Colonel Rodin and Donald Sinden as blustering British government official Mallinson. In a decision that allows the cast to perform without an artificial constraint, most are also allowed to retain their native accents rather than feigning French ones, and while this should theoretically jar with the casting of French actor Michel Lonsdale as Lebel – whose hangdog face and gentle delivery is put to excellent use here – so good are the performances across the board that this is never an issue. Only in Ronald Pickup's slightly colourful turn as the forger who foolishly tries to get one up on the Jackal does the reality bubble become briefly stretched, but this economically helps to cast him as someone on whom the Jackal can demonstrate his lethality without damaging the bond that we have formed with the assassin.

Best of all, however, and almost stealing the film from Fox in just two brief scenes is the always delightful Cyril Cusack as the gunsmith who constructs Jackal's custom made rifle. The soft-spoken Cusack is just wonderful here, from his calmly business-like inquiry about whether his customer will be going for a chest or a head shot ("Will the gentlemen be moving or stationary?" he then asks with chillingly detached politeness) to his appreciative response to the accessory design he is presented with, a system of containers whose dual purpose is not revealed to us until the Jackal is ready to use it. And in keeping with the film's attention to realistic detail, the gun he delivers feels like the real deal, a small number of interconnecting parts that assemble into a featureless but utterly plausible weapon. In another of those inexplicably effective moments, the quality of the gunsmith's workmanship is somehow communicated when the Jackal rests the assembled weapon on his hand and it balances perfectly – once again I'm not sure that this really signifies anything, but it feels like it does. This gives rise to the film's most quietly brilliant sequence, a wordless scene in which Jackal tests the rifle in deserted woodland, one that culminates in the firing of an explosive bullet into a suspended watermelon, the result of which is horrifying in its implication.

Zinnemann cannily contrasts the progress of both Lebel and the Jackal in a number of ways. While Lebel has all the resources he requires at his disposal, Jackal works largely alone and gets by on his skill and his wits, and while Jackal's preparations are often wordlessly executed, every aspect of Lebel's investigation is driven forward by conversation. By cutting between these two divergent approaches, Zinnemann keeps the content varied without impacting on the pace, which never falters. Our loyalties are also increasingly tested as the story progresses, as we let slip a satisfied smile when information that could identify Jackal is uncovered just too late to stop him crossing the border, then become frustrated by how the sluggish process of collecting information on hotel guests gives him the time he needs to move on before the authorities can reach him (and then quietly cheer that he's again been able to give them the slip). Later, when the time comes to switch our allegiance and get behind Lebel's efforts to stop the Jackal, a colder, crueller aspect of his personality emerges, and his willingness to dispose of innocent individuals to cover his tracks puts a necessary strain on that sympathy bond.

Everything clicks perfectly here, resulting in a beautifully engineered and utterly riveting thriller that Roger Ebert cannily noted is "put together like a fine watch," and that really does reward repeated viewings. There are a good many characters and story strands here to keep abreast of here, but there's never any confusion about where we are, who we are dealing with, or how each story strand will impact on the others. Ralph Kemplen's editing won a BAFTA (and was Oscar-nominated) and justifiably so, but this is a film in which every aspect of the production, from Kenneth Ross's superbly structured screenplay to Jean Tournier's location cinematography and Zinnemann's pitch-perfect direction of his actors, is in sublime synchronisation. The result is one of the finest film thrillers not just of the 1970s but of the modern age, and one that – everyday technology aside – hasn't dated one bit. So, one of those perfect films for our proposed list? Maybe not quite, but boy is it close.

The initial UK DVD release of The Day of the Jackal featured that weakest of image options, a letterboxed, non-anamorphic transfer, which might have been tolerable on a 28-inch CRT TV but blown up onto a large plasma screen makes for frankly grim viewing. About a year ago I discovered an HD print of the film on iTunes, which was a considerable improvement, but the 1080p 1.85:1 transfer on Arrow's Blu-ray is without question the one I have been waiting for. The image quality here is downright gorgeous, boasting a sharpness and crispness of detail that leaves even the iTunes version standing, and with no obvious evidence of digital enhancement. The contrast is beautifully balanced throughout, punchy but never harsh when the lighting allows and appropriately softer on interiors lit by incandescent light, but always attractively so and never looking remotely weak or washed-out. The colour reproduction is also superb, with the pastel shades of many interiors contrasting nicely with the naturalistic tone of the daylight exteriors, while prime colours are bright without feeling over-saturated. The transfer is also clean, with no dust or trace of damage, and a fine film grain is visible throughout. An excellent job.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is also in good shape, with clear reproduction of dialogue and no distortion on even louder sound effects and no background hiss or damage. The expected small range restrictions are hardly noticeable, particularly as there is no music score for the majority of the film.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

In the Marksman's Eye (36:00)

Author Neil Sinyard (who has written books on William Wyler, Alfred Hitchcock and Jack Clayton, amongst others) offers a thoughtful, detailed and heartfelt appreciation of a film he clearly admires every bit as much as I do, and often for the same reasons – he too singles out the rifle practice sequence and Cyril Cusack's performance as highlights. The genesis of both the film and the novel are outlined here, and the film is contextualised in relation both to Zinnemann's career and British cinema of the early 1970s. Usefully, this is headed up with a spoiler warning, one that you should definitely heed if you've not seen the film.

Location Report (2:37)

A brief French location report recorded in front of Montparnasse station in Paris, where the climax of the film takes place. An unidentified member of the production team talks about the casting of De Gaulle and the public's response to the crew's recreation of the station front as it was back in the early 1960s.

Fred Zinnemann Interview (2:52)

Another brief French location report, this time recorded in the village Tourtour in the Var, where Zinnemann answers questions (in French and subtitled in English) on his reason for casting the then relatively unknown Edward Fox and returning to the country where he studied in his younger days. Some behind-the-scenes footage has also been included.

Theatrical Trailer (2:04)

One of those trailers from the 70s narrated in an urgent voice by what sounds like Patrick Allen. It does give a flavour of the film's pace and tension, but also includes a few spoilers and thus should be avoided by newcomers until after the film itself, though does includes a shot from the rifle practice scene (no pun intended) that was not used in the film itself (the one that was used is way better).

Original Screenplay

If you're interested in seeing how close Zinnemann stuck to Kenneth Ross's screenplay, and in what small but sometimes significant ways he deviated from it, then this is for you. I certainly found it fascinating to compare favourite scenes from the movie to the script, particularly when Zinnemann has chosen to use not only Ross's dialogue, but also his suggestions for camera angles and scene structure. Just one thing, it's provided as a PDF on the Blu-ray disc and you'll need a Blu-ray drive connected to a computer to access this. Also included in the first pressing of the retail version of this disc is a collector's booklet featuring new writing by critic Mark Cunliffe and film historian Sheldon Hall, but this was not available for review.

One of my favourite films lands the transfer I've been dreaming of since we all went digital. The extra features are not as plentiful as those on some Arrow Blu-ray releases, but the Neil Sinyard interview is enthralling and the brief French location reports are also of interest. For the film and the transfer, however, this still comes unreservedly recommended.

|