|

Seemingly every day I marvel at the role that chance plays in our lives and fate. Trace any important event in your life back far enough and you'll discover that it might not have happened at all if just one small and often uncontrollable thing in that timeline had gone a different way. Pause to look at your watch on the way to work one day and the few seconds it delays you could mean you don't get hit by that speeding lorry just a couple of minutes later. Or maybe you do get hit by it because you halted your journey for those few crucial moments. As an example, I feel comfortable in the knowledge that I'm with my current partner because I made a conscious effort to win her affections, but the circumstances that brought me to that location in that town at that time and led to us even being aware of each other's existence hang on the results of a seemingly infinite number of coin tosses. To perhaps more dramatically illustrate the point, my late mother's life was once saved because a particular doctor just happened to be passing the emergency room just as she was fading away, and made a suggestion that turned out to be the answer to a puzzle that had the attending staff bewildered. Had he been stopped and questioned by a colleague just a few minutes earlier, or turned left instead of right at a particular corridor or realised he'd left something back on the ward, my mother would have died.

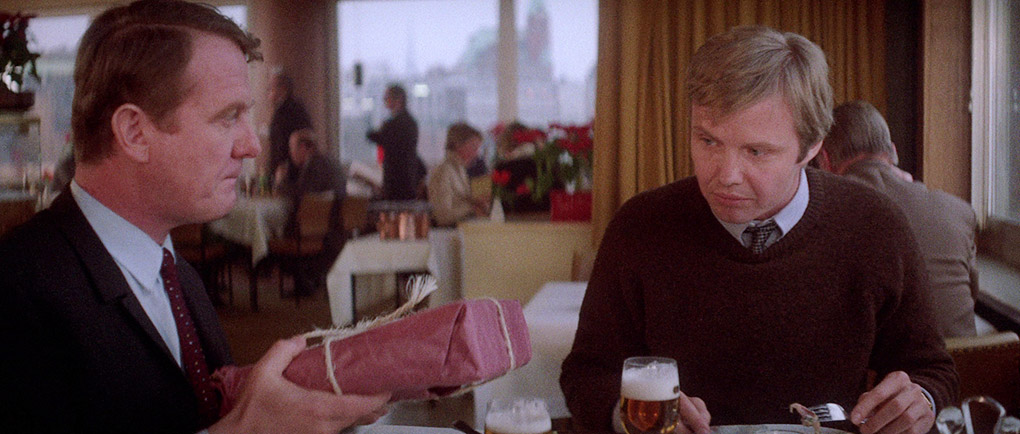

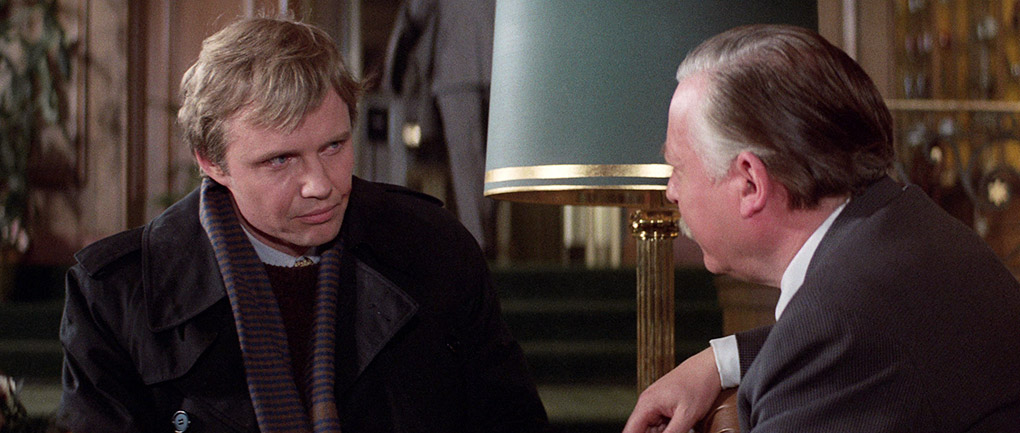

Chance plays a similar role in the 1974 film adaptation of Frederick Forsyth's The Odessa File. It begins in Hamburg on the night of 22 November 1963, when young freelance reporter Peter Miller (Jon Voigt) stops his car to listen to a news report about the assassination of US President John F. Kennedy. Due to this delay, he stops at traffic lights he would otherwise have passed though, and while waiting is passed by a small police and ambulance convoy that he immediately follows in pursuit of a potential story. On reaching what he initially believes to be a crime scene, he is informed by his friend and police contact Karl Braun (Gunnar Möller) that an elderly man has committed suicide. Nothing of interest here for this eager young reporter. The next day, Karl invites Peter for lunch and hands him a file that was found beside the victim's body and suggests that it will make interesting reading. Indeed, it does. The old man was Jewish Holocaust survivor Salomon Tauber, and the papers detail his experiences in the Riga ghetto and Jungfernhof concentration camp during World War 2 and the appalling mistreatment and murder of prisoners by sadistic camp Commandant, Eduard Roschmann (Maximilian Schell). Moved by what he has read, Peter becomes determined to locate and expose Roschmann, and calls on the help of celebrated Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal (Schmuel Rodensky), from whom he learns of a secret organisation of former SS officers known as ODESSA. His investigations hit a number of brick walls but also come to the attention of a group of Israeli agents looking to infiltrate ODESSA in order to prevent a planned germ warfare attack against their country. They kidnap Peter to find out what he knows, then convince him to go undercover as a former SS officer who is seeking assistance from the ODESSA group.

I first caught The Odessa File some years ago, and on the announcement that Indicator were to release it on Blu-ray, I tried to recall a single thing about it and found that I couldn't. For reasons I care not to expend too much thought on, it hadn't made a significant an impression on me. I was thus looking forward to revisiting it, and watching it afresh was an intriguing experience, prompting a mix of emotions and responses that altered as the film progressed.

One of the biggest hurdles facing The Odessa File is that the film adaptation of a Frederick Forsyth's first novel, The Day of the Jackal, is a near-perfect example of how to adapt a literary political thriller for the big screen and sets an impossibly high standard for any future movies based on the author's work. Of course, it's also likely that the success and critical acclaim that greeted that film on its release was the primary reason that Forsyth's second novel was snapped up and filmed the following year. Like its predecessor, The Odessa File has links to real-life figures and events and weaves political intrigue into the fabric of a thriller. But how does it shape up as a film entertainment?

It certainly gets off to an uneasy start and just ten minutes in risks breaking that cardinal film rule that says you should never tell an audience something that you can show them when Peter sits down to read Tauber's diary. What follows next is driven primarily by voice-over, and instead of telling their own story, the black-and-white flashbacks of Tauber's concentration camp experiences that accompany them function largely as illustrations of Tauber's spoken recollections, which are interspersed with shots of the studious Peter poring silently over the text. Remember how thrillingly cinematic the early scenes of The Day of the Jackal were? Dammit, I need to stop comparing the two. This sense of cinematic hesitance is enhanced by dialogue that is little more than functional and the decision to have the actors speak English in German accents.

OK, before I go on I feel I need to explain my issue with that, as in many ways it's not an issue at all. Indeed, although I'm not German by birth or even remotely competent at the language, I was immediately struck by the seeming authenticity of Jon Voight's accent, the apparent result of considerable work and study on his part. It's a glum fact that the German accent is too often overplayed to the point of parody in British and American films, and one thing that always struck me when conversing with German friends and associates was that they spoke English well and often with an accent that whilst clearly detectable but rarely pronounced, and Voight absolutely nails that mode of delivery. Now I'm not sure if the film was shot in chronological order, but in the early scenes, there's almost the sense that some of the non-German actors are delivering their lines how they think that a German who had learned but not quite mastered the English language would. And there's a lot of talk in the first third of The Odessa File, as Peter pokes around for information on Roschmann and gets nowhere until he talks to Simon Wiesenthal. And while this is definitely of interest, it's never as gripping as the riveting build-up in… well, you know, that earlier film, despite a hair-raising moment when Peter is pushed into the path of an oncoming train.

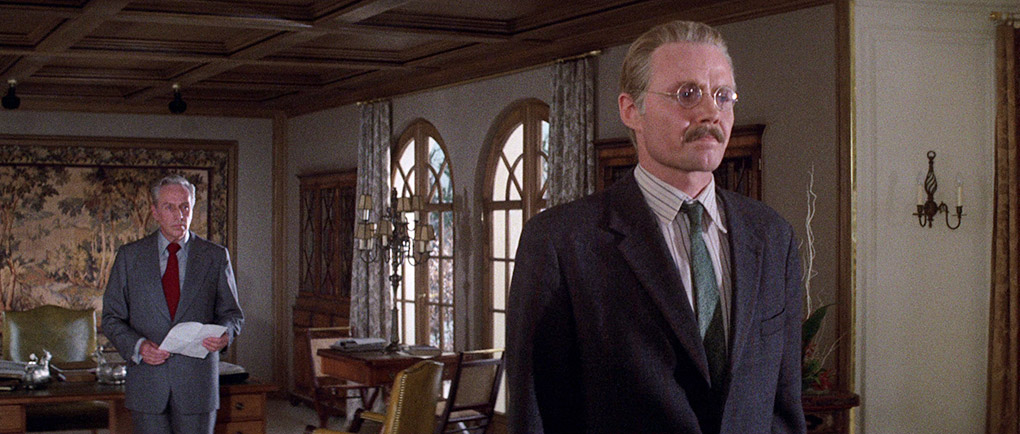

Yet once Peter is nabbed by the Agents of Israel and agrees to go undercover as an ex-SS officer in hiding, the film seems to become more focussed and more effective as a thriller. Although the preparation itself is not covered in detail and whole weeks skip by in a few efficiently montaged minutes of screen time, as Peter learns the details of his new identity's backstory off by heart and small changes to his appearance are made to subtly age him, I found myself getting hooked. But it's when Peter in questioned by a high-ranking ODESSA officer about the specifics of his new identity that the film really starts to exert a grip. The process by which his story is carefully cross-checked is convincingly handled and is allowed to play out in increasingly tense real time, as the logically thorough nature of the interrogation looks repeatedly set to catch Peter out and the unspecified preparations shown being made earlier start to make sense. There's a slight "oh, come on!" frustration at the thoughtless manner in which Peter later betrays himself, but this leads to lengthy but nail-biting scene in which he has to carefully stake out the location of his potential assassination and find a way of sneaking up on and outwitting the man who has been sent to kill him. This is all the more effective for again being allowed to play out in real time, and without the distraction of music or dialogue.

Cameraman-turned-director Ronald Neame (he of Tunes of Glory, The Horse's Mouth and The Poseidon Adventure) directs without much flair but with a robust eye for story momentum and is able to milk tension from a scene by showing restraint where others might bellow. He's certainly well served by a generally solid multinational cast, with notable turns from Maximilian Schell as Roschmann and – cementing the link to The Day of the Jackal – Derek Jacobi as the nervous and mother-protective forger Klaus Wenzer. I have to admit to having less enthusiasm for Andrew Lloyd Webber's score, a largely generic if occasionally effective orchestral piece that intermittently switched to electric guitar twangs to remind us in what decade the film was made.

There are still small but slightly annoying inconsistencies and logic holes, and although I still feel it lacks that certain something that has seen similarly themed movies work their way onto favourite film lists, I certainly got more out of it this time around than I did on my dismissive and long forgotten first viewing. And at a time when right-wing extremism is on the rise in Europe and America and its Racist-in-Chief is constantly demonising the free press and shamelessly encouraging violent action against its noble practitioners, the scene in which Peter attends a meeting of old Nazis and is led outside and beaten for taking a photo could almost have been ripped from recent headlines.

OK, we're getting used to praising the picture quality on Indicator releases now, but the 2.35:1 1080p transfer on this Blu-ray is one of their most remarkable yet, utterly gorgeous in every respect and really showcasing Oswald Morris's handsome scope cinematography. The contrast is spot on, with robust black levels but no serious sucking in of shadow detail, while the colour is vibrant without feeling over-saturated and the sharpness and picture detail are consistently strong. There's no sign of damage or dust and the image sits rigidly firm in frame. Superb.

Also in fine shape is the Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack, which while lacking the bass response of later Dolby tracks still boasts an impressive clarity and dynamic range, which is especially evident in the bright and lively reproduction of music (including that damned title song).

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

The BFI Interview with Ronald Neame (66:32)

Another of those valuable audio recordings of filmmakers being interviewed at what was back then known as the National Film Theatre, this chat with director Ronald Neame was conducted on 19 October 2003 by Matthew Sweet, who asks good questions but gushes a bit at the end by suggesting we all write to our MPs and ask why Neame hasn't received a knighthood. Neame himself is far more entertaining than this might suggest, recalling his entry into the film business, his first film job working for Alfred Hitchcock on Blackmail, how the decision to transform this into the first British sound film meant dubbing Anny Ondra's strong Czech accent live in the studio and how the noise made by the arc lights meant that the lighting and the sound departments were constantly at war on the film. He talks about the joy of working for Arthur Rank ("What film would you like to make?"), how the studio went downhill fast once the accountants took over, and there are some revealing of stories about working with Alec Guinness, Judy Garland and Albert Finney. Oh, there's loads more. Terrific.

The BFI Interview with Oswald Morris (61:28)

As if the Ronald Neame track was not special enough, also included here is an audio interview with cinematographer Oswald Morris, which was conducted by Anwar Brett at the National Film Theatre on 14 May 2006. Once again, this is a lively and entertaining chat, with particular focus on the films Morris photographed for John Huston. Subjects covered include: the final stunt fall and the casting for The Man Who Would Be King; the prep work for creating a specific colour design for Moulin Rouge, Moby Dick and Fiddler on the Roof; designing a specific look for Sidney Lumet's The Hill; shooting Lolita for Stanley Kubrick (a director he admired but wouldn't have worked with again – he's not the only one, apparently) and plenty more. I was particularly amused to learn that director Carol Reed detested musicals, and only took on Oliver! because he liked working with children – on the big musical numbers Morris claims he was "impossible."

Safe but Real (2:31)

Stuntman Vic Armstrong recalls working on the film and doubling for John Voigt for the train stunt. Watching the sequence again, I could swear that's Jon Voigt rolling under the platform as the train approaches, and grabbing a still from the sequence seems to cionfirm it. I presume the stunt was the shot leading up to that. Either way, it was a dangerous move that you had to do for real back then, and as Armstrong points out, with CG at every filmmaker's disposal, they wouldn't do that way now.

Foreign Friends (6:17)

Continuity Supervisor Elaine Schreyeck recalls meeting Ronald Neame, whom she loved working with, and how well they all got on with the German crew members.

Super 8 Version (16:48)

These have become something of a favourite Indicator extra, and though I always pass brief comment on them, I've never been specific about how critically damaging it is for any film to have its running time reduced from over two hours down to a paltry 16 minutes. The result, inevitably, plays like hurried essay notes for the real thing, and the process of carving out so much of the footage changes and massively over-simplifies the story. Thus here Peter chases an ambulance, briefly meet with Karl and in the blink of an eye is in a restaurant with him (how did we get here?) and being handed Tauber's papers, which he skims through in a jiffy and learns precious little about the suffering of the inmates. In no time at all he's in the hands of the Israelis and agrees to go undercover, and after a few seconds of train and a makeover, he's ready to go. The lengthy interrogation by the ODESSA officer is nowhere to be seen, Derek Jacobi's not in it, and the showpiece sequence in which Peter sneaks up on his would-be assassin has been reduced to a quick final tussle. Oh, and the picture has also been cropped to 4:3. If you saw the film for the first time in this form, you really would wonder what the hell you were watching.

Theatrical Trailer (2:01)

Following a textual introduction from Forsyth assuring us the story is the result of meticulous research, a ploddingly paced trailer unfolds, one whose grim-voiced narrator assures us, "The story is true. The ending will startle you." It probably won't.

Image Gallery

17 slides of publicity stills, posters and press material, and even a photo of the 45rpm single of the German folk song-influenced tune Christmas Dream that runs under the film's opening credits, which was composed by Andrew Lloyd Webber, Tim Rice and Andre Heller, and sung by Perry Como. Not one I'll be buying.

Booklet

Following full credits for the film, this typically strong booklet kicks off with a well-reasoned essay on the film by critic, journalist and curator Carmen Gray, who is not above questioning elements that do not stand up to scrutiny. This is followed by a fascinating exploration of the film's cinematography and its use of colour by Dr Keith M. Johnson – I genuinely hadn't thought about the film in these terms. Next is an extract from director Ronald Neame's autobiography, Straight from the Horse's Mouth, in which he looks back at the experience of making the film and straight up confirms my theory that it came about in part because of the success of The Day of the Jackal. He also reveals that the film was protested during a festival screening by neo-Nazis, who found the film "offensive." I'm liking it more by the second. Finally, we have extracts from reviews of the time, and once again it's a case of "I wish I'd read this before scribing my own review," as the introduction reveals the film was the victim of comparisons with a certain other Frederick Forsyth film adaptation whose title I've mentioned too many times already. That said, the quoted reviews find plenty of other aspects to pick holes in.

I'm still not completely sold on the notion that The Odessa File is an underrated and too often forgotten gem from the 1970s. It's safe to say that I enjoyed in more than I did back when I was first exposed to it, though when looking for a word to describe it I still kept settling on "workmanlike" rather than "exciting" or "enthralling." Yet there's good stuff in there and I can't fault its presentation on this excellent Blu-ray – the transfer is immaculate and is backed by a strong collection of special features, with the two NFT lectures and the booklet stealing the show. If you're a fan of the film, you need to get this disc, and if you're new to it then this is definitely the way to see it first. Recommended.

|