|

I'm not sure how it is in other countries, but in the UK the word 'incident' is often loaded with implication, particularly if it is coined by an authority figure. If a policeman shows up at your door and tells you that your son has been involved in an incident, you can be fairly sure that he's either in serious trouble or has been injured. If we're told there's been an incident involving two naval vessels of opposing nations, thoughts of possible hostile escalation or even war will not be far from our minds. Thus, when presented with a film titled The Incident, I went in expecting trouble. I didn't know the half of it.

During the course of a 10 minute pre-title sequence, the film paints a no-nonsense picture of its antagonists and what they are capable of. Two young punks named Joe Ferrone (Tony Musante) and Artie Connors (Martin Sheen) are playing pool when the owner of the hall ambles over to politely remind them that he's closing up for the night. "You touch that switch and I'll tear your arm off," responds Artie coldly as he chalks up his cue. The owner's response is to nervously instruct his subordinate not to extinguish the lights over this particular table. The boys finish their game, intimidate the owner a little more and then head out into the deserted New York streets. It's long after midnight on Sunday and everything is closed up, but Joe and Artie are hyped-up and still in the mood for nefarious fun. When they can't find a car to steal they hide in an alleyway and mug a passing pedestrian, pinning him down painfully and threatening to stick the switchblade Artie is brandishing into his ear if he attempts to resist. The ensuing robbery nets them a meagre eight dollars, and after forcing him to beg to be released they let the man up. Then, as he turns to walk away, Artie knocks him to the ground and beats him with a ferocity that must have left him critically injured or dead. Amused by their actions, the two then head off towards Times Square in search of something else to amuse them.

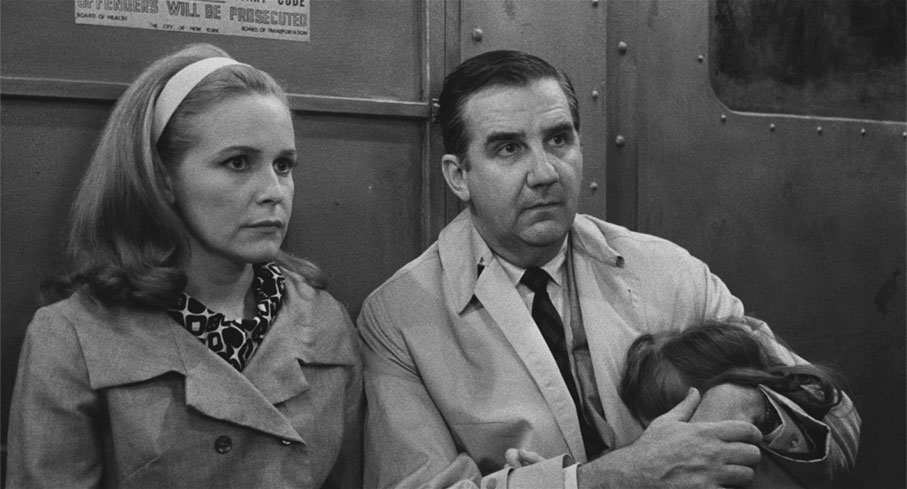

There are several ways in which The Incident is socially and cinematically forward-looking, and the first example is here in the establishment of a palpable threat that will then be kept under wraps until after we've spent time getting to know its potential victims. It's a formula that has become something of a trope of modern horror cinema but proves effective here because it clues us in from the start to the inevitability of an upcoming confrontation, one that none of those making their way to sperate stations on the subway line to Times Square has even an inkling that they are soon to be part of. In this respect, the subsequent character introductions anticipate the structure of 1970s disaster movies, as we meet a range of couples and individuals and are given economic insights into their often troubled backstories. First up we have Bill Wilks (Ed McMahon), his wife Helen (Diana van de Vlis) and their sleeping young daughter, whom Bill is carrying. Bill is bitching about the late hour and how little sleep he'll get before having to go to work in the morning, yet when Helen hails a cab, Bill immediately complains about the cost and even rejects Helens offer to pay for it with the claim that he'll end up paying her back in housekeeping anyway. When they reach the station it emerges that Helen wants another child and is genuinely shocked when Bill reveals that he is firmly against it, claiming that their daughter was "an accident" anyway. Next we meet Alice Keenan (Donna Mills), a virginal teenager who is out on a date with unpleasantly pushy would-be lothario Tony Goya, who keeps on manhandling her and trying to kiss her despite her protestations. Eventually he assures her that she'll never get anywhere in life with that attitude and acts all standoffish, which prompts the insecure Alice to give in to his advances and the two end up locked in a constant snog. Heading for the next station, meanwhile, is elderly and bickering Jewish couple Sam and Bertha Beckerman (Jack Gilford and Thelma Ritter). Sam is angrily sounding off about how the young should be taking care of the old and showing them respect, and nothing his wife says seems able to calm him. From their conversation it seems likely that complaining about anything and everything is Sam's favourite pastime, one that his long-suffering wife has wearily learned to live with.

By this point it struck me that a pattern was emerging, one in which every woman we met seemed to be getting a raw deal from men who were all self-centred arses. It thus came as something of a relief when we encounter Phillip Carmatti (Robert Bannard) and Felix Teflinger (Beau Bridges), two army privates on furlough who've just had dinner with Carmatti's Italian-American parents. Oklahoma-born Felix is nursing a broken arm and Carmatti is desperate to get out of the army, go to law school and make it rich as a lawyer. Up next is Muriel Purvis (Jan Sterling) and her put-upon husband Harry (Mike Kellin), whom Muriel berates for not pulling in the sort of wage that the host of the cocktail party they have just attended makes, also slyly blaming him for their lack of children and curtly dismissing his quietly spoken revelation that he was checked out by his doctor and that his equipment is working fine. At the next stop, unemployed former alcoholic Douglas McCann (Gary Merrill) is approached by lonely young homosexual Kenneth Otis (Robert Fields), who previously made a nervous but ultimately failed effort to talk to him in the bathroom of a nearby bar and whom Douglas angrily sends on his way. Finally, we're introduced to African-American couple Arnold and Joan Robinson (Brock Peters and Ruby Dee) and that earlier male-female relationship pattern is firmly re-established. Arnold is angry at just about everything in this white-dominated society, something he expresses loudly and frequently despite the protestations of his calmer and more level-headed wife.

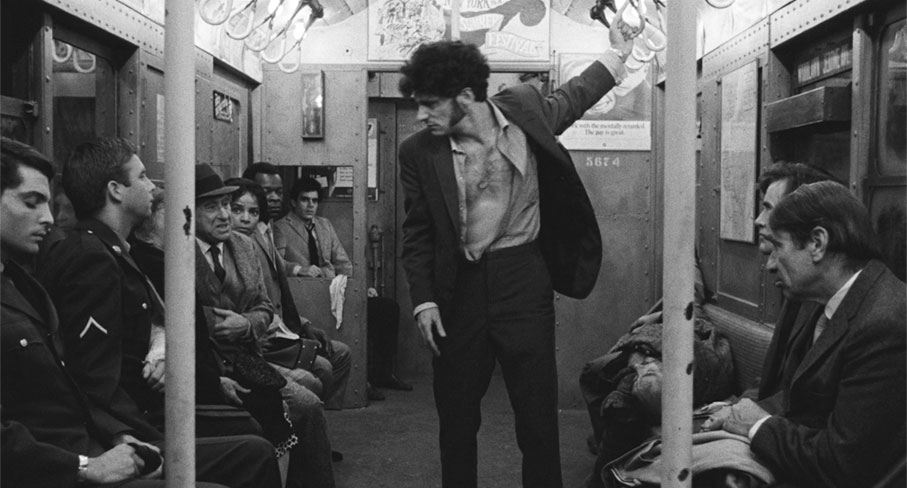

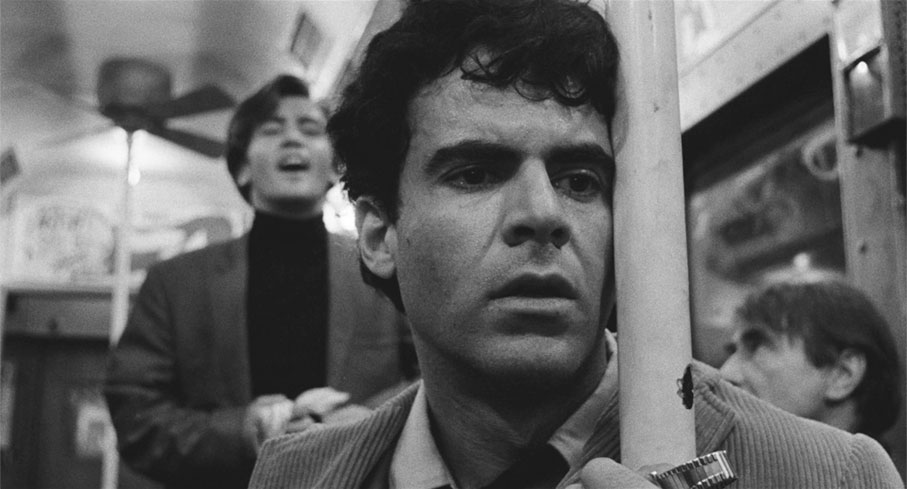

All of these characters end up in the same car of the same train, each of them boarding at a different station. A throwaway line and some unobtrusively placed signs clue us in to the fact that only one of the carriage's doors is working, and a panicky change of heart on Kenneth's part about boarding the same car as the disapproving Douglas makes it clear that the connecting doors are firmly locked. It's once all are aboard, of course, that the still hyperactive Joe and Artie jump on board, squealing with noisy delight as they swing around poles and charge up and down the carriage in an explosion of childish piggyback tomfoolery, bumping into passengers and grabbing items of clothing. Almost all of the car's other occupants are made to feel uncomfortable by the antics of the two young men, but nobody says a thing. It's then that Joe and Artie turn their maliciously playful attention to the other occupants of the carriage.

That the passengers will eventually be terrorised by Joe and Artie is signposted from an early stage – you don't show what these two are capable of and then drop them out of the story unless you're planning to bring them back later – and the fact that everyone we meet ends up in the same carriage on the same subway train tells us where this will happen. And having seen what Joe and Artie will do for kicks, we have good reason to dread the moment they inevitably make their appearance, and it's here that the lurking dread of the first half is transformed into serious discomfort and mounting fear. We may only know a little about each of the passengers, but we connect with them anyway on an empathic level. I realise that I'm talking from personal experience, but I'm guessing that there are few reading this who have not at one time in their life felt directly or indirectly threatened in a public space by someone whose wild and unpredictable behaviour made them fear for their safety. I'm aware that such an experience is uncomfortable in part because the perpetrators are breaking the unspoken societal code of conduct, one that dictates how we should behave when in the company of people with whom we have no prior relationship. This rears its head in the film even before Joe and Artie board the train, when Sam and Bertha take their seats and Sam is outraged by the sight of Tony and Alice passionately kissing on the seat opposite, not because of what they are doing but because they are doing it in a public space where the social norm is that you should show a level of restraint. But if sex is something that people are embarrassed by unless it takes place within the confines of their own home, public displays of aggression are a different story. They carry with them the risk of violence, and this is something that our inbuilt instinct for self-preservation has in most cases programmed us to steer clear of, especially when we cannot predict the severity of the outcome. For most of us, physical and even verbal violence is something to be avoided and that even if witnessed can prove upsetting or even traumatising. This reaction is as biological as it is psychological, an inbuilt fight-or-flight response that has enabled us to survive as a species and that can be triggered by something as simple as an angry individual asking you what the fuck you're looking at. Yet try responding to that primal urge to flee when you're trapped in a train carriage whose only working door is being blocked by the very thing you're hot-wired to run from in the first place. And in The Incident, it's in that very carriage that director Larry Peerce keeps us and the passengers claustrophobically trapped for the entire second half of his nail-biting film.

Of course, Joe and Artie's rampage could theoretically have been sharply cut short if the passengers had made a collective stand against them, and a small number of commentators have viewed their reluctance to do so as a weakness of the film, one that punctures its otherwise discomforting realism. While I see where they're coming from, for me this element is crucial and believable, not just in its reflection of the time and place in which the film is set but in the way that it unknowingly looks forward to a time where we fear – perhaps unduly – that aggressors of all ages might just be carrying a potentially lethal weapon that they have absolutely no qualms about using. It's this fear of being targeted and the possible consequences, coupled with the distancing effect of finding themselves in the company of strangers to which they have no emotional or familial ties, that prompts the passengers in this film to do what people all over the world so often do in similar situations and look away and keep silent in the hope that they will not be picked on next. It's an aspect of the film that I have no doubt resonated with a local audience on the film's release, when the 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese – who was stabbed to death outside of her apartment in Queens in full view of 38 witnesses, none of whom came to her aid or even thought to call the police – was still a haunting memory and that gave birth to a psychological theory known as the Bystander Effect. This is exactly what happens when Joe and Artie, after playing games with an unconscious drunkard, target the terrified Kenneth in a deeply upsetting and painfully lengthy homophobic attack. During the course of his long ordeal, nobody seems willing to stand up for the petrified Kenneth, and in a moment that speaks volumes that I missed the first time around, once Artie starts in on him, the adjacent Arnold and Joan subtly shift along the seat a little to put some distance between then and the unfolding harassment. A short while later when Kenneth directly begs Arnold to help him, his response is to stay silent and awkwardly look away. It should be noted that by this point a warning shot to the passengers has already been fired after Douglas verbally challenges Artie and Joe over their potentially harmful toying with the helpless drunkard (an empathic response from a man who is a recovering alcoholic himself, perhaps) and they respond by intimidating him into silence.

I'm sure it's not by chance that those first targeted by Joe and Artie are all solo travellers, which numerically pitches the odds against the victims from the off and by the time the aggressors move on to those travelling in pairs they have shown clearly what they are capable of. Even with the backup of a partner to call on, most are reluctant to say or do anything, even when directly confronted or threatened. Again, this has its basis firmly in reality. Even the most outraged of the passengers would likely find his or her response constrained by their own inexperience of violent confrontation, and further by an inbuilt degree of restraint that's installed into most of us at an early age by the rule of law and the potentially life-changing consequences of actually doing what instinct may make us want to. What's particularly interesting about this dynamic as it plays out in the film is the emasculating effect that it has on the more belligerent male passengers and how it strips away the public facades them and their partners and exposes them for who they really are. When Joe starts harassing Alice, for example, the previously tough-acting Tony becomes sheepish and compliant, and while the ever-complaining Sam does eventually pipe up in protest, it's Bertha who angrily dishes out an angry slap, the only physical resistance put up by anyone to this point.

Understandably, particularly given the instinctive bravery that saw three young American servicemen charge a gun-wielding terrorist on an Amsterdam to Paris train in August of 2015, the surprise expressed by those aforementioned commentators that no-one is prepared to confront Joe and Artie does tend to focus on the inaction of soldiers Phillip and Felix. Again, this has to be viewed in context. When we first meet them, we learn that Phillip can't wait to get out of the army, into which he was probably conscripted and to which is clearly ill-suited. Felix, on the other hand, is handicapped by an injury whose cause is never revealed and that Felix himself seems reluctant to talk about, and every time he appears on the verge of intervening, he is dissuaded by his clearly more reluctant comrade. I found myself concocting an entire backstory for Felix's injury, one that explained why he would not want to get into a fight in which might lose all control, a theory that is then tested when Joe and Artie start pressuring him and he responds with an intriguing mixture of cool control and apprehension and nervously admitting that Joe would likely beat him senseless in a fight (the fascinating manner in which this confrontation concludes is worthy of its own analytical paragraph, but you should be free to draw your own conclusions on this). Arnold's perverse enjoyment at seeing the white passengers suffer, meanwhile, seems spectacularly naïve given the bigoted nature of the harassment of the homosexual Kenneth, and his suggestion to Joe that he is somehow on their side prompts an inevitable and unpleasantly hateful response.

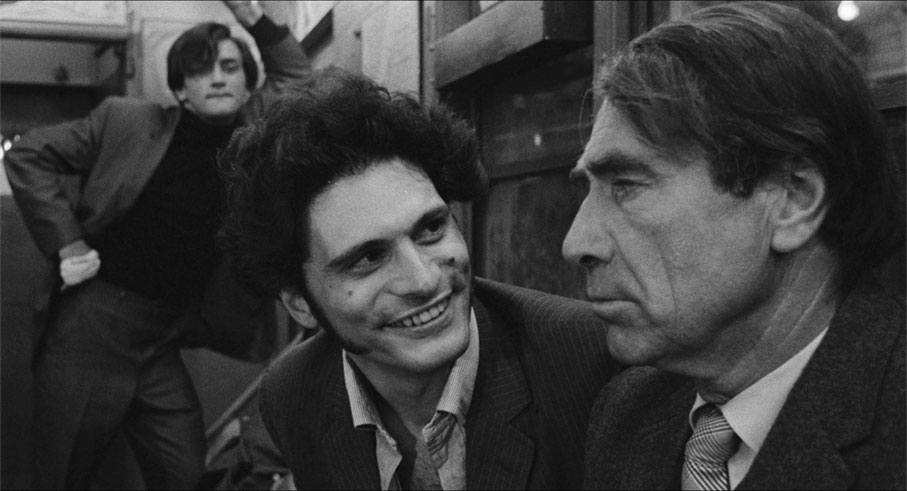

Exactly what lies behind Joe and Artie's behaviour is never explored but this never feels like a shortcoming of a film where the focus is less about their actions than how others respond to them. We're clued into the fact early on that Artie in particular gets what sounds like an adrenal high out of terrorising others, and we can presume from the conversations he has with Joe that this is how they've been getting their kicks for some time. The extremity of their behaviour and their insanely high energy level may suggest the influence of drugs, but no direct reference is made to any substance that they might have taken beyond the booze bottle from which Joe occasionally takes a swig. Occasionally Artie can be seen popping something into his mouth, but it's never confirmed whether he's ingesting sweets or amphetamines, and while shots of him chewing seem to confirm the former, I've seen enough people hyped on speed to wonder if just a little of the latter wasn't swallowed by both men some time earlier that evening. What makes these two particularly scary, however, is that they are not just mindless thugs and seem to have the ability, perhaps gained through experience, to quickly identify the weak spot of a victim and target it as much through what they say and how they say it as through cruder acts of physical intimidation. It's a key characteristic of some of the most realistically intimidating characters in modern cinema – think Don Logan from Sexy Beast or Sergeant Hartman from Full Metal Jacket – and one I have seen wielded to sickening effect in real life. Joe and Artie are dangerous not just because they have a sociopathic lack of empathy, but because they are able to instinctively vary their methods and know precisely how to get under the skin of those they pick on.

The performances are all superb, and I do mean all. Tony Musante and (in his feature debut) Martin Sheen are genuinely terrifying as Joe and Artie, their wild behaviour always believable and their verbal intimidation convincingly threatening enough to make the reluctance of others to engage them understandable. The discomfort and fear displayed by every one of the actors cast as the passengers is absolutely on the nose, so much so that even when someone you might initially have taken a dislike to is targeted there's no sense of satisfaction that they're getting their come-uppance, just a squirming empathy for what they are being put through and fear for where it might lead. On the special features, director Larry Peerce reveals that he rehearsed the actors in their character pairs, encouraging improvisation and giving Sheen and Musante a degree of free reign, which in one case involved them genuinely scaring seven bells of crap out of Ben Levi, the actor cast as their mugging victim.

I'll hold up my hands and admit that I wasn't even aware of the existence of The Incident until Eureka started posting tweets about its acquisition, and knowing that a review disc would eventually be landing on my doormat I deliberately avoided reading anything about it in order to go in cold, something I so rarely get the opportunity to do. It's safe to say that I was blown away by what unfolded. Structurally it's simultaneously smart and daring, establishing and even hanging out with the antagonists before putting them on hold to allocate the sort of screen time that even a big-budget disaster movie might balk at in order to clearly define the characters that destined to become the victims, then bringing them together and keeping them trapped in a single location for the entire second half of the film. By working in an enclosed subway carriage set with no fly-away walls (a studio set standard to make room for camera equipment and lighting when angles are changed), persuading the studio to allow them to shoot in black-and-white and lighting the main set with the set's in-built lamps, director Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld give the film an air of sometimes documentary realism, adding to the sense that what we are watching is less a drama than a recreation of an actual event, an incident if you will. And while I've let my keyboard run away with me a little, I feel the need to point out that there is so much more I could have written, including a weighty few paragraphs about the final ten minutes. I've elected to avoid delivering major spoilers on this one, even with my usual warnings, but will note that this finale includes an almost throwaway moment that apparently had black audiences up on their feet in anger on the film's release and whose commentary on race relations in America is so painfully relevant that the sequence in question could have been shot yesterday. It's one of many immaculately judged and multi-layered moments that richly texture this tense and superbly made and performed film, one whose observations about societal and empathic disconnect seem sadly to be as relevant now as they were in late 1960s New York.

No details have been provided about what looks like a restoration for the film's first appearance on Blu-ray, but the 1080p 1.85:1 transfer here is in excellent shape. While the black levels do soften a tad at times to retain picture information that might otherwise be swallowed by darkness, the contrast is otherwise well balanced and intermittently punchy, and the definition of the fine detail – particularly on facial close-ups – is impressive. Considering that the film was shot on Tri-X film stock and lit primarily with practical lighting, the transfer here looks better than I could ever have expected, and the grain, though visible, is nowhere near as coarse as I've seen it look with that particular film stock. There's also no image jitter or any sign of damage or dust. A really nice job.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack has some minor range restrictions, particularly at the bass end, but is otherwise clear and free of background hiss or damage.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

Audio Commentary with Larry Peerce and Nick Redman

Any special feature involving the late Nick Redman is always a pleasure and this commentary track, in which he plays host to director Larry Peerce, is no exception. It helps that Peerce is such an energetic and entertaining storyteller and that Redman, as ever, is so adept at asking questions that prompt interesting answers. Peerce outlines how the project came to be, how it began as an independent production and had to be put on pause until it was rescued by renowned producer Richard Zanuck, how they had to unofficially grab shots of trains and the actors on subway stations when the New York Transit Authority refused to let them film on their property with the comical claim that there were no violent incidents on the city subway, and that Peerce was later offered the chance to direct box-office mega-hit Love Story but decided that it wasn't for him. We get information on and stories about the actors, the rehearsal improvisations, that incendiary late addition to the finale, and so, so much more. This is an essential listen for anyone who admired the film. Terrific.

Audio Commentary by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas

Knowing that this second commentary was delivered by a critic rather than someone directly involved in the production, I was – somewhat uncharitably – not expecting to get quite as much from it as I got from the one involving Redman and Peerce. Boy was I wrong. Melbourne-based film writer Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, whose work I now feel obliged to track down and read, really goes to town on the structure and socio-political aspects of the film, as well as providing detailed information on almost every actor who has a line of dialogue and deconstructing their characters, their relationships and their motivations. This may sound a little scholarly, but in a film with such complex socio-political layering and such an extraordinary attention to detail, it absolutely is not. Some of her observations are so smart that they had me slapping my head for missing them or bleating "of course!" at the screen, something particularly true of some of her comments about Felix, which helped clarify the thinking behind the strange but oddly captivating way that Joe's harassment of him comes to an end. The fact that she uses almost the exact same words as I had written when talking about one aspect of the film is just something I'll have to suck up and live with – this happens to us a lot. Another excellent commentary, although be cautious of pushing the sound up too loud as when Heller-Nicholas starts to speak after even short gap the volume takes a leap before settling down.

Q&A with Director Larry Peerce (31:08)

As the title suggests, this is a recording of Q&A with Peerce following a screening of the film at the Wisconsin Film Festival, and while much – I'd risk saying most – of what he says is also covered in his commentary track, there is some information unique to this extra and some of the detail in the recollections does differ here. It's also nice to be able to put a face to the voice. This was shot from somewhere in the audience, and while visually and aurally clear, the on-camera mic also picks records the sound of a loudly creaking nearby seat. Ignore it if you can, it's worth it.

Theatrical Trailer (1:56)

A busy trailer that doesn't specify the plot but makes sure we know it's about conflict and includes press quotes that tell you how hard-hitting it is. They're not wrong. Brief shots from the later scenes could only count as spoilers if you watched this three times just before the film itself. So don't.

Booklet

Following the main credits, this booklet kicks off with a thoughtful essay on the film and its director by Samm Deighan, after which is a piece by Barry Forshaw on the film and the careers of director Larry Peerce and actors Martin Sheen and Tony Musante. Bringing up the rear is a reproduction of a pamphlet created and distributed by members of the New York City Police Department and handed out to people arriving at the city's airports, one that paints an alarming picture of the dangers posed by the city to the unwary. To give you a flavour, it includes sections titled, 'Stay off the streets after 6 P.M.', 'Do not walk', and 'Avoid public transportation'. Jeez. The booklet is illustrated with production stills and posters, the most interesting of which is – as is often the way – the Polish one.

Definitely one of the cinematic rediscoveries of the year, The Incident is a tightly constructed and richly layered work, one whose entire second half had me shifting in my seat in fear and whose filmmaking and performances kept me utterly riveted throughout. It's a film whose attention to detail really does reward second and third viewings, during which I spotted things that passed me by the first time around for the simple reason that I was so involved in the story and so wound up by what was unfolding. Eureka has done the film proud with this release, which sports a first-rate transfer, two excellent commentary tracks and a fine booklet. See this film. Highly recommended.

|