|

This is a late review. It's fair to say that most of the reviews we'll be publishing in the next few weeks will fall into that shameful category. I've outlined why in my recent blog, but despite the temptation to stop reviewing for a while and cope with my family issues, it's releases like this that make it impossible for me to do so. I'll get to why soon.

Late October proved a rich time for Blu-ray releases of films from UK horror specialists Hammer, with four titles released by Studiocanal (eight were promised, but four have been held up until January), and this intriguing collection from Indicator. It's perhaps no surprise that while a distributor of Studiocanal's clout and budget have plumped for some of the studio's better-known titles, Indicator have opted for four of the studio's less widely seen works. To the cynical eye, this may seem like a case of a small distributor getting lumbered with the scraps that were left after the boys with the bigger cheque books had finished feeding, and if that was your first thought on hearing about this box set then you're in for a surprise. It includes a belated follow-up to Hammer's 1959 The Mummy, an oft-forgotten flirtation with Greek mythology, and two of the studio's sometimes undervalued psychological thrillers, all with remastered HD transfers and newly created special features.

Despite my fondness for Hammer movies, I'll admit to having seen none of the films included in this set, and really enjoyed them all. And there's plenty to get your teeth into here, which is a principal reason why it's taken me so long to turn this review around. Effectively, what we have here are four individual releases – each with its own extras and booklet – in a single box set, and I've approached this review in that manner, something that is reflected in its length, which I'll not add to by stretching this introduction out any further.

And so, to the films.

The success of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho had a considerable impact on Hammer Films, particularly its suggestive, single-word title, something reflected in titles of subsequent Hammer thrillers such as Paranoiac, Nightmare, Fanatic (see below) and Hysteria. The second of these was the 1963 Maniac, a lurid title that in some ways makes promises that the film itself has no plans to deliver on, a deception its sensationalist poster art did its best to cheerfully foster. Go into this one expecting the pre-slasher exploitation flick the promotional material promises and you're likely spend much of the first half under the misapprehension that you've bought a ticket for the wrong movie (or put the wrong disc in the drive – you get my drift).

It certainly gets off to an attention-grabbing start. We're in the Carmargue region of France, where 15-year-old Annette is offered a lift home from a man who clearly has no intention of getting her there safely. Since she knows the driver in question, she cheerfully accepts his offer, but a concerned school friend sees them drive off and gives chase on his bicycle. When the man stops his car and drags Annette into the bushes, the boy shoots off and alerts Annette's father, but by the time he shows up the evil deed has been done. The furious father immediately wreaks his wrath on the man, first with a wrench, then later back in his garage with an acetylene torch. Being a suspense thriller from 1963, we don't get to see precisely what he does, but the screams should get your imagination sucking air through its teeth. Intriguingly, this opening sequence is conducted entirely in non-subtitled French – once the main story gets under way we move into universal translator mode, with all of the dialogue spoken in English, which is delivered in French accents by the locals. Whether we are supposed to infer that the non-French characters are fluent in French or all of the locals are speaking English for their benefit is neither certain nor particularly relevant.

A few years later American painter and drifter Jeff Farrell is stranded in the region when he is ceremoniously dumped by the girl whose money we can presume he was living off. Following her departure, Jeff finds lodging at the very bar at which Annette now works and that is owned by her mother Eve. Jeff is immediately attracted to Annette and she soon takes a shine to him, but Annette's mother also has designs on this good-looking visitor and is soon seducing him, much to young Annette's chagrin.

And this is how the rest of the film's first half-hour plays out, and does so with the sort of attention to character and brisk pace that genuinely made me forget that I was supposed to be watching a thriller. The cast certainly helps, with Jeff played by Kerwin Matthews, whom Ray Harryhausen fans will know as the lead player from The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad and The Three Worlds of Gulliver – he may not go out of his way to make Jeff that likeable, but he does keep him interesting enough for us to become sympathetic to his later plight. French actress Liliane Brousse is convincingly innocent and emotionally tortured as Annette (she's also, of course, blessed with a genuine French accent), but stealing the show here is Nadia Gray as Eve, whose interest and especially the nature of her interest in Jeff is written all over her face from the first time she claps eyes on him, while her subsequent seduction is both believable and tinged with a nicely pitched level of suggestive eroticism.

All this proves involving enough to ensure that when the change of direction that drives the film's second half does kick off, it's initially a little jarring, disrupting what had the potential to develop into an interesting love triangle drama, one that would feel quite at home in this rural European setting. Indeed, so attractive is the location work here that despite my admiration for Wilkie Cooper's crisp monochrome scope cinematography, this is one Hammer psychological thriller that I found myself secretly wishing had been shot in colour.

Once you become acclimatised to the gear-shift, however, the screws quickly begin to tighten, as Jeff is pulled into a scheme that if he was thinking with his head instead of his gonads he would doubtless not have agreed to so readily, and he soon finds himself seriously out of his depth. It's a journey peppered with unsettling sequences (just who is firing off the acetylene torch in the barn at night and disappearing before they can be discovered?) and enough plot twists to keep you on your toes, only one of which I saw coming from some distance away and that would not have been that difficult to more effectively disguise*.

So, ignore the sensationalist implications of the title and prepare yourself for a first half that is effectively build-up to a tense and twisty gear-shift in the second and appreciate the film for what it is, a neat melding of character drama and thriller that boasts some solid performances and assured direction from Michael Carreras, makes terrific use of some eye-catching locations (the quarry climax is particularly striking), and sports a handful of genuinely unsettling scenes. Chalk another win up for Hammer's lesser-seen psychological thriller strand.

The only black-and-white film in this set sports an impressive 2.35:1 HD transfer, with an attractive tonal range and solid black levels. The image is sharp with crisp rendition of detail, a very fine film grain and no trace of any former dust or damage. The daylight exterior shots look terrific, but night-time sequences have been lit for clarity and also look fine.

The Linear PCM mono soundtrack is also in fine shape, with clear reproduction of dialogue and music, though it doesn't quite have the crispness of the following two films in the set.

Subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have also been included on all four discs.

White-Hot Terror: Inside 'Maniac' (10:59)

Following a spoken introduction by Claire Louise Amias, American Gothic author Jonathan Rigby and cultural historian John J. Johnston discuss a number of aspects of the film, from its use of the scope frame and impressive location work, to the actors and performances and changes made in the transition from script to film.

Hammer's Women: Nadia Gray (7:51)

Dr. Lindsay Anne Hallam, Senior Lecturer at the Moving Image Research Centre at the University of East London, provides a useful overview of the career of actor Nadia Gray, who plays Eve in the film and whose penultimate screen role was in a favourite episode of The Prisoner, The Chimes of Big Ben.

Focus Puller Trevor Wrenn and Clapper Loader Ray Andrew on 'Maniac' (5:09)

In what has become a familiar special feature on Indicator discs, two of the technical staff on the film share a few memories of working on it. Intriguingly, Wrenn tells a story about Andrew that Andrew himself says nothing about, making me suspect that Andrew was interviewed first.

Trailer (2:28)

Plenty of spoilers here, including footage of the climax. Save for later.

Original Promotional Material

64 slides of promotional stills, lobby cards, press book pages and posters, all in crisp HD.

On-Set Photography

24 monochrome behind-the-scenes still from collections owned by producer Jimmy Sangster and director Michael Carreras.

Booklet

In common with the other three typically fine booklets here, this one is headed up with a spoiler warning for the material within, which begins with a wonderfully written essay on the film by genre writer and enthusiast, Kim Newman, one that made my own coverage feel positively anaemic. Next up, there's a substantial interview with director and later managing director of Hammer, Michael Carreras from a 1978 edition of House of Hammer magazine, and a sizeable extract from Jimmy Sangster's 2001 memoir Inside Hammer, in which he discusses his screenplay for Maniac. Film credits and promotional artwork have also been included.

| THE CURSE OF THE MUMMY'S TOMB (1964) |

|

Of the trio of Hammer updates of classic Universal monster movies that effectively established the house horror style, The Mummy was the last to get a follow-up film. While the 1957 The Curse of Frankenstein was followed the next year by The Revenge of Frankenstein, and the 1958 Dracula by The Brides of Dracula in 1960, fans of the 1959 The Mummy had to wait five years for a second movie.

I've already discussed my childhood conviction that the Egyptian mummy as the scariest of all the classic movie monsters in my review of the third and weakest of Hammer's mummy films, The Mummy's Shroud. As it happens, this fear was based on a furtive late-night viewing of single movie, Karl Freund's 1933 The Mummy, whose black-and-white eeriness and bandaged Boris Karloff haunted my imagination for years to come. Later, when I first discovered the Hammer remakes, colour seemed somehow inappropriate for a creature that is effectively monochrome by nature, but that first Hammer movie, with its Freudian symbolism and physically imposing creature (hats off, once again, to Christopher Lee) soon became a personal favourite nonetheless.

Unlike Hammer's Dracula movies, which with the exception of the aforementioned The Brides of Dracula, were each direct sequels to the previous film in the series, the four films in the Mummy series are narratively unrelated and have only the title creature in common. The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb kicks off in Egypt in 1900, where a British archaeological team has uncovered the tomb of the Egyptian prince Ra, and expedition leader Professor Dubois has been captured by a band of hostile locals, who kill him and cut off his hand as a trophy. The rest of the party – Sir Giles Dalrymple, John Bray and Professor Dubois' daughter (and Bray's girlfriend) Annette – are warned of the curse that will befall anyone who violates the tomb, but they dismiss these claims as archaic superstition. None of this will come as a surprise to anyone who's ever seen a mummy movie before – Pharaoh's curses are to mummy movies what the infectious bite is to werewolf tales and is even spelt out in the title. Sir Giles and his Egyptian colleague Hashmi Bey plan to exhibit the discoveries at the Cairo museum, plans that are upset when brash American expedition sponsor Alexander King reveals that he instead intends to clean up by taking Ra's coffin and mummy on a world tour. Sir Giles promptly resigns and King puts Bray in charge of the project, but before they depart for London their camp is ransacked and a catalogue of the artefacts is stolen by an unknown party. On the boat journey home, Sir Giles is attacked by a knife-wielding man and Annette is only spared due to the forceful and timely intervention of fellow passenger Adam Beauchamp. He takes an immediate interest in the party and their discoveries and invites them to stay with him at his home in London, where he begins quietly romancing Annette. A short while later, she produces an amulet given to her by her father, one sporting an ancient hieroglyphic inscription that immediately piques Beauchamp's interest and which Bray takes to the now persistently inebriated Sir Giles for help in translating.

It's worth noting that we're halfway through the film by this point, and I'm sure I'm not the only one who was by then wondering when the curse of the title would come to pass. It's a while longer before the title creature makes its first animated appearance, by when we've been treated to a couple of flashbacks to explain how and why Ra met his untimely end, watched King dress-rehearse his colourfully carnival-esque opening of Ra's coffin, and learned to distrust oily woman-stealer, Adam Beauchamp. It's after Bray discovers that the medallion's hieroglyphics reveal an incantation for reviving the dead, and the Mummy disappears from its coffin on the press preview of King's roadshow, that the creature sets out to punish those that have violated its resting place. But just who is behind its reanimation and the numerous assaults on Sir Giles and his colleagues, and how can this lumbering but lethal creature be stopped?

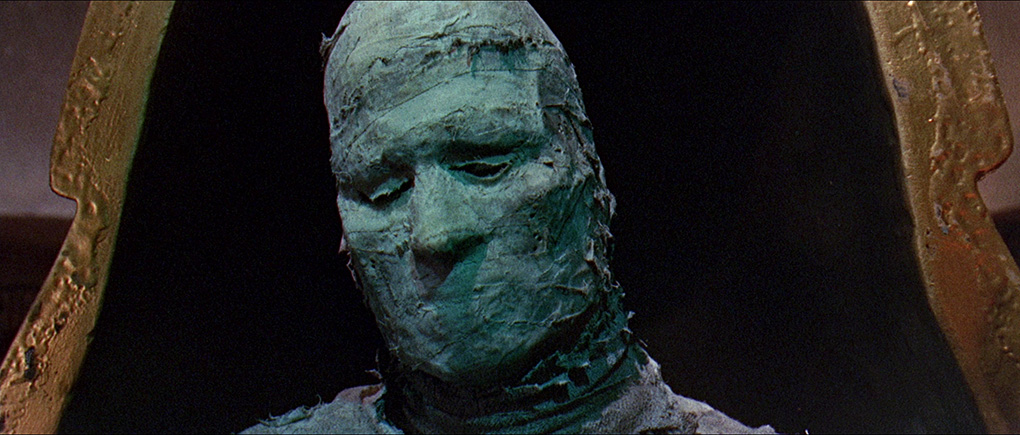

There are a few issues here. The fact that a number of the Egyptians are played by English actors in brown face (including Hammer regular Michael Ripper) has not aged comfortably, and the locals who dispose of professor Dubois in the opening scene cackle in wild triumph like extras from Carry on Up the Khyber. Working class Londoners, meanwhile, are portrayed as superstitious cowards, idle shirkers or avaricious shrews, and clearly inferior to their middle-class betters. And while it's easy to dislike Beauchamp for making moves on Bray's girl, she doesn't help matters by agreeing with his claim that intelligent women might be happier putting their gifts to use in the home instead of chasing a career. There's also an oddly incongruous moment when Bray mimics the lumbering walk of a mummy from movies that will not exist within the timeline of this story for another thirty years or so. The mummy itself, meanwhile, breathes like Darth Vader and looks less like his head is bound in crumbling cloth than the sort of plaster bandages in which broken limbs were once cocooned.

Compensation is provided by the solidly structured drama that precedes the inevitable rampage and some typically robust performances from a cast that features none of Hammer's star names (American comedic actor Fred Clark is particularly entertaining as Alexander King). Cinematographer Otto Heller, whose impressive CV includes Peeping Tom, The Ladykillers, Alfie and The Ipcress File, also compensates a little for the Mummy's less than imposing nature by intermittently casting it in sinister shadow. The level of violence is occasionally surprising for a film of its vintage (something that apparently raised a few concerns with the BBFC), particularly a scene in which the Mummy kills a willing victim by stepping soundly on his proffered head, and there's a particularly good final act twist that I genuinely didn't see coming.

Despite these qualities, The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb is neither as thematically layered or dramatically riveting as its highly regarded predecessor, or as stylish and inventive as the fourth film in the series, Blood from the Mummy's Tomb. But it still has a very real edge on its follow-up feature, The Mummy's Shroud, and inkeeping with many of Hammer's second-drawer features, even at its shakiest, it's always entertaining.

A sharp and wonderfully detailed 2.35:1 transfer with nicely balanced contrast, crisp black levels and sometimes vivid colour reproduction. Elsewhere there's a warmness to the colour that's typical of Hammer films of the period. Once again, the image is sparkling clean and a fine film grain is pleasingly evident.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono track is in excellent shape, with crisp reproduction of dialogue and music and a far better dynamic range than I would expect from a (dare I say British) film of this vintage.

Blood and Bandages: Inside 'The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb' (13:05)

Claire Louise Amias again provides the introduction and Jonathan Rigby and John J. Johnstone the film analysis, here focussing on the cast (Fred Clarke rightly gets the most love), with special mentions for the film's technical adviser Andrew Low, a lively shipboard punch-up, that final act twist and a wink-at-the-audience scene in which two characters inadvertently provide the name for Turkish Delight.

Hammer's Women: Jeanne Roland (10:54)

Diabolique magazine editor-in-chief Kat Ellinger outlines the film and TV career of Jeanne Roland, whose voice was dubbed with a French accent for the film, something I was too dopey to appreciate while watching. She also explores the character of Annette Dubois, finding interesting connections to characters in Bram Stoker novels and the work of French philosopher Jules Michelet.

Interview with Actor Michael McStay (5:59)

Actor Michael McStay, who plays Ra in the flashbacks and the Mummy in the main story, recalls shooting the sequence where Ra's hand is severed and recognised by name actors for his role in the film because they'd all watched it on TV the previous evening.

Interview with Composer Carlo Martelli (4:12)

A brief interview with composer Carlo Martelli, who focusses primarily on the source music that he arranged for the film, examples of which are played and handily captioned with their titles and composers.

Super 8 Version (6:53)

A black-and-white silent Super-8 version that compresses 88 minutes down into a dizzying six, with blocky subtitles providing the dialogue when relevant. It dispenses completely with the film's first half to focus on the Mummy's disappearance and subsequent killing spree. The scratches and damage give the footage an unexpected recovered documentary feel in places.

Theatrical Trailer (3:01)

"WARNING!" barks the sinister voiceover as the word itself is plastered across the screen, a voice that then advises each of the lead actors to "BE-WARE!" of the creature that's featured heavily here in what we are assured is "The terrifying story of a bandaged and rampaging monster."

Image Gallery

A beefy collection of 129 slides of production stills, posters, garishly coloured-in lobby cards, and pages from the film's press book, all crisply rendered.

Booklet

Following full credits for the film, we have a well-researched and interesting essay by Kat Ellinger, imposingly titled Egyptian Gothic: Hammer, Egyptomania and the Victorian Morbid Spectacle in The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb. Next up, we have information on the key cast members from UK and US press books, and some intriguing further extracts from these documents detailing some of the ideas suggested for promoting the film. I really enjoyed these, which included ideas such as, "What better street stunt could you have than a real live 'mummy' at large in the streets? An undoubted attention-getter all for the price of a few rolls of bandages." Absolutely. Finally, we have an unsigned and comically slanted contemporary review from Films and Filming.

It's sometimes nice when your expectations for a film – which are based on little more than films that have gone before – are undermined by what actually unfolds on screen. Take the 1964 The Gorgon, a Hammer production directed by Terence Fisher and starring Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing. As any horror fan worth their salt will cheerfully tell you, the trio of Fisher, Lee and Cushing were responsible for a number of the studio's most celebrated works, including The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Dracula (1958) and The Mummy (1959), which made household names of Lee and Cushing and collectively drew up a template for the studio's horror house style. When Lee and Cushing topped the bill, you knew that they were going to be playing the two characters around which the story would revolve, and that they would very likely be in conflict with each other. In The Gorgon, they are once again billed as the stars, but against expectations do not occupy the traditional role of lead players. Cushing does figure prominently but almost as a supporting character, and despite a brief appearance in the first half, we're almost 50 minutes into an 83-minute film before Lee plays a meaningful role in the drama.

If you're only familiar with the word gorgon as a derogatory term for a fearsome woman, know that its origins lie in Greek mythology and that it was a collective term for three sisters, each of whom had snakes for hair and power to turn anyone who looked upon their face to stone. Their names were Stheno, Euryale and Medusa. Ah yes, we've all heard of that last one, a woman who rose to international fame when she was beheaded by Perseus. To be honest, you don't need to know your Greek mythology before watching this film for the first time, but a little bit of awareness probably helps nonetheless.

The story here is set in the German village of Vandorf in 1910, where a local girl is murdered and her body turned to stone before the district's sole medico Dr. Namaroff (Peter Cushing) can perform an autopsy. It turns out that this is the seventh such killing in the district during the past five years, but no-one in authority, including the local police chief Inspector Kanof (Patrick Troughton), seems keen to investigate the truth behind these peculiar deaths. The girl's murder is instead blamed on her artist boyfriend, Bruno (Jeremy Longhurst), who proceeds to aid this scapegoating by hanging himself. His esteemed father, Professor Jules Heitz (Michael Goodliffe), is unconvinced by the accusations made against his late son, and thus travels to Vandorf to launch his own investigation.

Under normal circumstances, I'd expect Professor Heitz to be played by Peter Cushing, but he instead is part of the conspiracy of obstructive silence that Heitz and eventually his elder son Paul (Richard Pasco) have to do battle with in order to get to the terrible truth. Lee's late film arrival as the no-nonsense Professor Karl Meister, meanwhile, is perfectly timed, confidently sweeping in when Paul is most in need and imposing enough to kick a sizeable hole in Namaroff and Kanof's collective wall of bluster.

All of which helps to differentiate The Gorgon from the other, more classical monster-driven Hammer horror works of the period. It's certainly one of the most visually handsome, thanks in no small part to Dracula: Prince of Darkness and Rasputin: The Mad Monk cinematographer Michael Reed, whose vivid use of light and colour here is not just eye-catching (something especially true of this restoration and transfer), but also contributes towards the film's consistently unsettling atmosphere. It probably matters little that the Gorgon here is identified as Megaera, who in Greek mythology was actually one of three 'Furies' (the others were Tisiphone and Alecto, in case you were wondering), a creature who inspired jealousy and envy and who punished those guilty of marital infidelity. What does sting a little is that when we finally get to see her up close, the sense of horror that we should experience is seriously tempered by the dismayingly inflexible mechanical snakes that adorn her otherwise decently-made-up head.

In all other respects, however, The Gorgon is an effective and too-often forgotten work from Hammer's golden period. A well-devised and unpredictable narrative, strong performances (Cushing is at his low key best here and Barbara Shelley shines as his assistant Carla, whom the older Namaroff is secretly in love with), tight direction, atmospheric cinematography and a rare flirtation with Greek mythology all contribute to its unique tone and feel. The fact that the transformation to stone is a gradual one allows for an intriguing scene in which a victim is horribly aware of what is happening to him, and even builds the sort of physical one-on-one battle that made the climax of Hammer's first Dracula such a thrilling experience. The result is a neat sideways step by Hammer on their monster movie formula, and another worthy rediscovery for this splendid box set.

A gorgeous 1.66:1 transfer whose detail is sharper, whose colour is vibrant and whose contrast is robust with solid black levels and no sign of obvious black crush. It really flatters Michael Reed's lovely cinematography and lighting and there's no distracting dust or traces of any former damage. So crisp is the image that it reveals a couple of times when the focus was just off and the production presumably had to make do with what they had.

Dialogue and music both sound fine on the Linear PCM 1.0 mono track, and there's no background hiss or fluff in the quieter moments.

Audio Commentary with Samm Deighan and Kat Ellinger

The knowledgeable team of Samm Deighan and Kat Ellinger, the driving force behind both Diabolique Magazine and the Daughters of Darkness podcast, deliver a detailed exploration of the film, the principal cast members and, especially, how it was influenced by or is connected to a range of literary and film works, movements and sub-genres. It may require some patience and concentration to absorb in a single sitting and much of it is clearly being read from a pre-prepared script, but the chances are you'll come away enlightened and with a whole new appreciation for the film.

Heart of Stone: Inside 'The Gorgon' (14:01)

The usual trio Amais, Rigby and Johnson cover Plague of the Zombies and The Reptile John Gilling's unhappiness with the changes made by Anthony Hinds to his original script, how Peter Cushing dominates the proceedings as neither its hero or villain, director Terence Fisher's emotional connection to the material, how the film is often unfairly perceived as a whodunit, and more.

Hammer's Women: Barbara Shelley (9:28)

Patricia MacCormack, currently Professor of Continental Philosophy at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge and Chelmsford, brings up some interesting points about the film's narrative and even what's absent from it, recalls getting up at 2am as a child in Australia to watch Hammer movies, salutes the performance of Barbara Shelley, and even makes a case for why the dodgy nature of the mechanical snakes on the Gorgon's head make it even more scary. Much as I respect MacCormack and her views, I'm not convinced on that one.

Matthew Holness on 'The Gorgon' (14:51)

Actor and writer Matthew Holness discusses what he describes as one of Hammer's bleakest films and its first to have a female monster, with specific focus on director Terence Fisher and the specifics of his direction. Good stuff.

Theatrical Trailer (2:47)

The 'terrifying realism' of The Gorgon is championed in a solid-enough trailer that avoids major spoilers.

Original Promotional Material

102 slides of promotional and behind-the-scenes stills, lobby cards, posters and press book scans.

Comic Strip Adaptation

35 slides featuring what looks like all the panels from a comic strip adaptation that originally appeared in the August and September issues of House of Hammer magazine, both of whose covers are also featured here.

Booklet

Full credits for the film are followed by an authoritative, substantial and well-researched essay by genre writer (and director of some of the extras in this set), Marcus Hearne. Next up is a reproduction of a piece from a 1977 edition of House of Hammer magazine that revisited the film and spoke to director Terence Fisher and actress Barbara Shelley, which is followed by extracts from a 2010 interview with Shelley from Fangoria magazine. Rounding things off are some entertaining extracts from the UK press book featuring suggestions for a number of promotional gimmicks, which include an eye mask to shield your eyes from the Gorgon's lethal stare, and somewhat suspect advice on how to "create an atmosphere of emergency in your foyer." William Castle would be proud.

The 1965 Fanatic, we are informed in one of the extra features on this disc, was the first of Hammer's psychological thrillers to be shot in colour and the first to be influenced by its American backers, whom we can credit with insisting on the American leads. Frankly, I think we owe them a debt of gratitude. It's also, structurally, the almost polar opposite of Maniac, another Hammer thriller included in this box set whose suggestive, single-word title was likely shaped by the success of Psycho. In Maniac, we're over halfway through the film before it really starts earning its thriller credentials, whereas here we're less than ten minutes in before the warning bells start ringing.

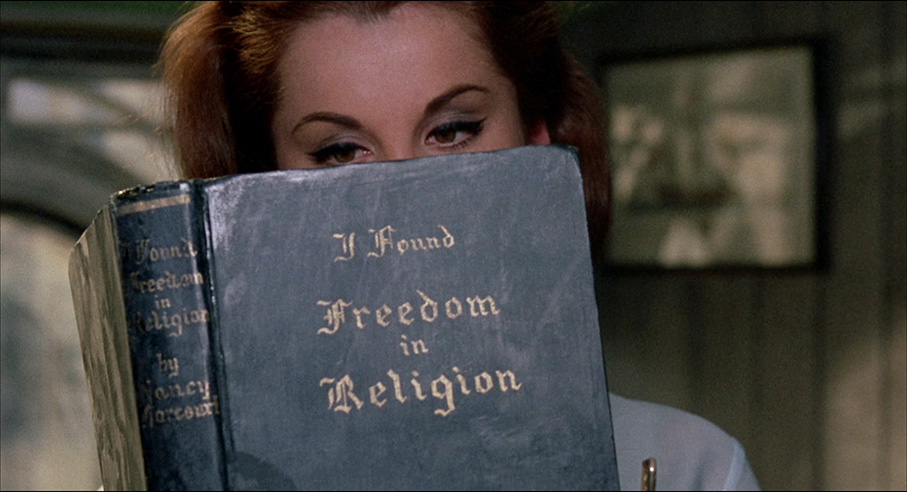

Before tying the knot with her boyfriend Alan, Patricia Carroll decides to pay a respectful visit to the mother of her former fiancé Stephen Trefoile, who died in a car crash several years earlier. Mrs. Trefoile welcomes her into her isolated country home and insists she stay the night, but Patricia soon finds herself having to pay tactful lip service to the elderly woman's obsessive religious beliefs. Initially a tiresome inconvenience – there are no mirrors in the house, the wearing of lipstick is judged as sinful, and achingly long prayer sessions are held before every grimly flavourless meal – this takes a more sinister turn when Mrs. Trefoile, with the help of her married servants Harry and Anna and mentally challenged handyman Joseph, prevents Patricia from leaving and makes it her stated mission to cleanse Patricia's soul.

Any delusion that we're in for an even remotely comfortable ride is dispelled from the moment Patricia walks into the Trefoile house, as she's eyed-up by a shotgun-wielding Harry, frostily ushered in by Anna and greeted a little too eagerly by a host whose hospitality she is simply too polite to refuse. By the time she becomes aware that Mrs. Trefoile has moralistic designs on her soul, the house has become a prison guarded by a husband-and-wife team whose unquestioning obedience is later revealed to be driven by factors other than blind devotion.

In some ways Fanatic looks forward to some of the more tortuous horror-thrillers of the 1970s and beyond, ones in which a usually female protagonist falls victim to a demented individual or family and is subjected to an unrelenting run of mental and/or physical abuse, from the terrifying ordeal of Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) to the teeth-grinding discomfort of Steven Sheil's Mum & Dad (2008). For Patricia, there's just no respite here, her suffering peppered with false hopes that are almost immediately dashed, which has the effect of grinding us further into our seats and, in spite of the year of release, had me repeatedly concerned that Patricia was not going to make it out of this alive.

Tautly directed by Canadian émigré Silvio Narizzano, Fanatic boasts one hell of a cast, and much of what makes the film so consistently gripping is down to the performers. In what almost prefigures his sinister handyman role in Joseph Larraz's still too little seen Symptoms, Peter Vaughn is both imposing and creepily lecherous as Harry, while Yootha Joyce cuts a memorable figure as his wife Anna and Patricia's frosty and physically threatening custodian, one whose vulnerability is gradually unmasked as the situation complicates. Stefanie Powers is terrific as Patricia, bounced as she is through a range of emotions from amusement to irritation to outright terror, all of which she plays with the sort of conviction that had me chewing my fingernails in empathy from the moment things take their first sinister turn. And yes, that's a young Donald Sutherland walking a fine line as the emotionally damaged Joseph.

But stealing the film and every scene she appears in is Tallulah Bankhead's extraordinary performance as Mrs. Trefoile. Larger-than-life yet at the same time terrifyingly real, her commanding, throaty delivery and stridently confident body language make Mrs. Trefoile a figure of genuine fear, a religious zealot who judges everyone by her own narrowly blinkered and warped definition of morality, one that she is prepared to impose that vision on the non-compliant with everything from forced imprisonment to a gun that she wields and fires with disturbingly casual ease. She's genuinely imposing within the confines of the narrative, but as an all-too-convincing representation of threat represented by religious fundamentalism she is more frighteningly relevant today than any of the studio's classical monsters. It's this, Richard Matheson's typically thoughtful screenplay (adapted from Anne Blaisdell's novel, Nightmare), Narizzano's direction and the excellent cast that give this too-little seen Hammer treat its longevity, and make it as tense, compelling and intermittently discomforting an experience today as it doubtless was back in 1965.

The most deliberately unglamorous-looking film in the set has still been very nicely transferred. Framed in its original 1.85:1 aspect ratio, there's an earthy hue to the palette that tends to lock the film to its time and place (English villages only seemed to look this way on colour film stocks of this period), but the brighter colours are still attractively captured. The detail is crisp but never quite pops in the manner of the other two colour films in this set, and while the contrast is generally fine, the black levels do occasionally pull in detail, though this is inkeeping with the down-to-earth aesthetic.

The mono 1.0 soundtrack breaks with the Linear PCM tracks of the other films in this set by being DTS-HD Master Audio. Surprisingly, the dynamic range falls a little short of that on the earlier The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb (though that is exceptional for a film of its vintage), but the dialogue, effects and music are all clear and there is no trace of any damage or background hiss.

It's worth noting that the disc offers the option to watch the film either under the original British title of Fanatic or the American title of Die! Die! My Darling. As far as I'm aware, the only difference between the two are the opening titles.

House of Horror: Inside 'Fanatic' (14:27)

The by-now familiar trio of Amais, Rigby and Johnson provide a concise examination of certain aspects of the film. Rigby prompted me to slap my hand to my forehead in realisation when he points out the numerous similarities between the story here and the first four chapters of Bram Stoker's Dracula and the similarities to Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard, and both men have plenty of good things to say about the performances. It's also here that I learned for the first time about the stage play Looped, which is covered in more detail below by its author, Matthew Lombardo.

Hammer's Women: Tallulah Bankhead (9:27)

Kat Ellinger makes another welcome appearance to discuss the career of Tallulah Bankhead and her colourful private life, and reveals that she was very ill during the making of Maniac, the result of her years of seriously hard living. This didn't stop her from misbehaving on the set, we are assured.

Fanatical Detail: Renée Glynne and Stuart Black on 'Fanatic' (8:51)

Continuity supervisor Renée Glynne and assistant director Stuart Black share a few memories of the shoot, the most colourful of which – no surprises here – involve Tallulah Bankhead.

David Huckvale on Composer Wilfred Josephs (13:48)

Author David Huckvale, whose book include Hammer Films' Psychological Thrillers 1950-1972 and Hammer Film Scores and the Musical Avant-Garde, provides an overview of composer Wilfred Josephs' career (I was intrigued to learn that he started out as a dentist) and then usefully deconstructs the technique and thinking behind large portions of his complex and playful score for Fanatic.

Playwright Matthew Lombardo on Tallulah Bankhead and 'Fanatic' (6:59)

An interview with Matthew Lombardo, the author of Looped, a play built around a real-life recording session in which a drunken Tallulah Bankhead took eight hours to redub a single line from Fanatic that was ruined (we learn from the accompanying booklet) when the boom operator walked into a bush. There's an intriguing air of fate to the news that when actress Valerie Harper was forced to abandon the lead role due to serious health issues, she was replaced by none other than Stephanie Powers.

Theatrical Trailer (2:31)

This one's for the film under its American title of Die! Die! My Darling, which the colourful narrator says repeatedly in a voice that's only a cackle away from being an upper-class supervillain. There are enough quick-cut spoilers to warrant giving this a pass until after the film itself.

Image Gallery

59 slides of promotional photos, coloured-in front-of-house stills, poster artwork and pages from the promotional press book.

Booklet

This one kicks off with a thoughtful essay on the film with specific focus on Tallulah Bankhead by BFI National Archive programmer, Jo Botting, which is followed by selected extracts from interviews with Bankhead (who lives up to her reputation for the repeated use of her favourite word with responses like, "I needed the money, dahling," and "I just adore a drink, dahling. Who doesn't?") and director Silvio Narizzano on the film. There's a full interview with Narizzano conducted in 1977 by John Fleming for House of Hammer magazine, in which the director talks about changes made to Richard Matheson's original script, working with Tallulah Bankhead, the special effects and more. Next up is a brief but useful interview with screenwriter Richard Matheson, and a welcome interview with Stephanie Powers on the play Looped – it's she that confirms that the fault for the ruined line of dialogue did not lie with Bankhead but the boom operator. Rounding things off is a contemporary review by Tom Milne from Monthly Film Bulletin. The expected credits and promotional imagery are both on board.

What an unexpected treat this box set is, showcasing the fact that Hammer were responsible for a more than just the classical monster movies with which they are chiefly associated, one of which has been included here for balance. All four films have plenty to recommend them and are all handsomely presented and showered with worthwhile special features. You really are getting four individual releases here in one unifying set (they even have their own individual boxes and covers), and for Hammer fans especially, this is a must have. I genuinely can't wait to see what will be in Volume 2. Highly recommended.

|