|

What crosses your mind when you realise the film you're about to watch was made by Hammer? Chances are the studio's phenomenally successful run of horror movies will come to mind, stylish remakes of old Universal classics that updated a number of key horror franchises and filmed them in colour with an increased level of eroticism and violence. If you're a Hammer fan, you'll likely also know their psychological thrillers, most of which were shot in black-and-white even after their horror films had made colour a stipulation. It's worth noting, however, that Hammer had been around for 22 years before landing a major international hit with The Curse of Frankenstein. Early on, the studio had a string of domestic successes with film adaptations of much-loved BBC radio series and efficient B-movie quickies, but what is often forgotten is that they continued to make non-horror films even after The Curse of Frankenstein, Dracula and The Mummy had redefined the studio's image.

In its previous Hammer box set, Hammer Volume One: Fear Warning, Indicator paired two of Hammer's lesser-seen horror works with two of its psychological thrillers. In this second set, we have four crime thrillers, all made between 1958 and 1961, the period in which Hammer was busy establishing itself as the world's premier producer of horror cinema. And despite all being intended as supporting B-features, they're really quite something.

Of all the films in this Indicator box set, The Snorkel was the one I was the most apprehensive about. My reasons were all superficial. Let's start with the title, which is not remotely threatening nor particularly suggestive of storyline or genre. The word 'snorkel' is something I tend to associate with sunny childhood holidays by the sea, and is not, I would venture, a title that would lure today's curious thriller fans to gravitate towards the film. And then there's the British poster, which is featured on the cover of the Blu-ray case within the box set here and seems to be trying to present the film's snorkel-wearing antagonist as a Jason Voorhees-like killer. It might have looked creepy back in 1958, when fewer people knew what a snorkel actually was, but now leaves the poor fellow looking a little silly. What was I in for here?

Any such concerns are allayed – and then some – by the wordless and instantly intriguing pre-title sequence, in which an unsettlingly blonde man (think Robert Shaw in From Russia with Love) completes the job of sealing up the doors of a room with tape before disposing of two milk glasses, one empty and one full. He then produces two lengths of rubber hose and the eponymous snorkel, climbs down through a hidden trapdoor into a crawlspace beneath the wooden flooring, where he connects the hose to two short pipes that feed through the wall to the exterior of the house. After then connecting the other end of the hoses to the snorkel, he extinguishes the flames of all of the gas lamps in the room and then turns them on again without lighting them, after which he takes a seat, puts on the snorkel and waits for the gas to kill the unconscious woman we have since become aware is laid out on a sofa. A short while later, a maid arrives at the house to prepare a meal and the man retreats into the hidden crawlspace. When the maid brings up the food, she is alarmed by the locked door and the smell of gas and urgently alerts the gardener, who breaks down the door and opens the windows. The police and the British Consul arrive (we've worked out that we're in Italy by this point, albeit without being explicitly told) and a verdict of suicide is declared. When the dead woman's teenage daughter Candy turns up, however, she instantly claims that her mother was murdered by her stepfather, Paul Decker.

It's a seductive and impeccably handled setup for a plot that most should be familiar with by now, one in which a vulnerable woman suspects a dangerous man of murder but no-one believes her, and she thus embarks on an investigation of her own, which puts her in increasing danger as the man in question becomes aware that she's on to him. Here, however, the conflict between Candy and Paul has been on the boil for some time, back from when she saw him murder her father by holding his head underwater whilst pretending to rescue him, a claim that was also dismissed by those close her. And having watched Paul meticulously faking his wife's suicide in the opening scene, there's no ambiguity over his guilt in this matter – he killed Candy's mother to get full control of her money, so there's every reason to believe that he also killed her father to get access to it in the first place.

With that in mind, we're encouraged instead to side with Candy as she looks for evidence to confirm her conviction. It's a quest in which she is aided by her loyal dog Toto, who initially proves to be a better detective than her. When she's searching Paul's room for his passport in an effort to prove that he couldn't have been in France at the time of her mother's death, for instance, Toto makes a b-line for the snorkel in his wardrobe, only to have the distracted Candy tell him to put it back.

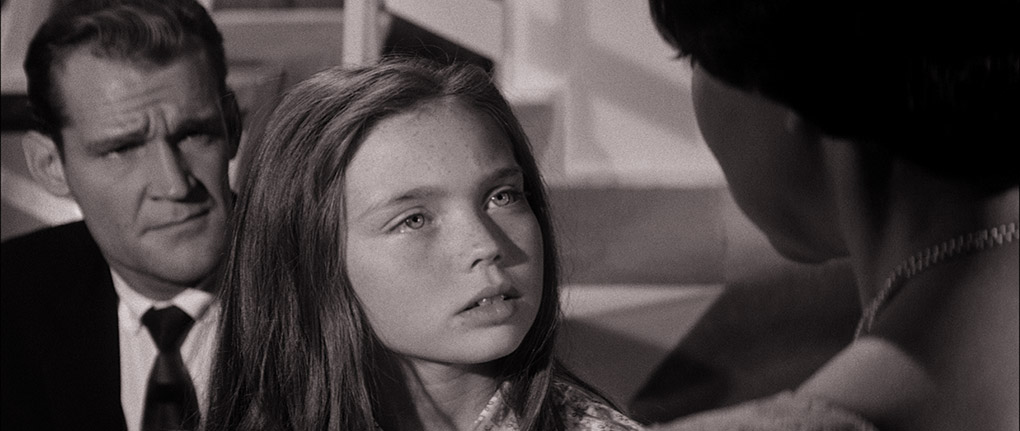

Paul's capacity for lethal violence and calmly intimidating demeanour, coupled with Candy's emotional isolation and physical vulnerability, helps to crank up the tension and give rise to a handful of unsettling sequences and a couple of very effective jump scares. That no-one will believe Candy effectively isolates her, and the then-young Mandy Miller does a fine job of convincing us that she is someone who is not going to be intimidated by the man she is absolutely convinced killed her parents, and that she will continue with her investigation whatever the risk. She also has no compunction about directly confronting Paul with her suspicions, and at one point turns her discovery of what a snorkel is actually used for into a song with which to openly taunt him, a move that provokes the blackest of looks from Paul. And as played by German actor Peter van Eyck, Paul represents a most palpable screen threat, carrying out the opening murder with the calm precision of a scientist setting up a routine experiment and infusing even quietly delivered lines like "You've been a naughty girl – I don't like naughty girls" with such an undercurrent of menace that his every encounter with Candy in the film's second half had me chewing my fingernails in anticipation at what he might do to her. Hell, this man even swims in a threatening manner, his hands held flat like steel shovels and his angle-locked arms rotating with the smooth consistency of a programmed swimming machine. If a Terminator took to the water, I'm utterly convinced this is how it would move through it. And while it's become something of a western film cliché to cast the guy with the foreign accent as the bad guy, there's an altogether more sinister subtext here, given that the opening scene consists of a blonde-haired German disposing of a woman by sealing her in a room and gassing her to death, a potent undercurrent for a film made just 13 years after the end of the Second World War.

It builds to a genuinely tense climax and what should have been one of the tonally darkest final scenes you'll find anywhere in Hammer's cinematic canon. Unfortunately it's also one whose spine-shivering effectiveness is a little undercut by a perceived need on the part of someone up high to soften its impact with what can't help but feel like a tagged-on ending, one that allows a key character to retain the moral high ground. Ultimately, however, this does no real harm to this taut and economical little thriller. Smartly directed by former cinematographer Guy Green and atmospherically photographed by Hammer regular Jack Asher, it's the sort of neatly made, no-nonsense non-horror B-movie that Hammer by this point had down to a tee.

A solid 1.66:1 monochrome transfer with an attractive tonal range and solid black levels that do not punish the shadow detail. Detail is sharp and the day-for-night material is graded appropriately without losing clarity. Some night interiors are darkly rendered with subdued highlights, but unless you're watching on an ageing plasma screen in a brightly sunlit room, clarity is not an issue. Dust and damage have been cleaned up and the film grain, though very visible, is cleanly rendered. There is some very minor flickering on a few shots, but on the whole, this is a very good transfer.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is also in solid shape, with clear reproduction of the dialogue and music, within the expected range restrictions imposed by the film's age. There's no trace of background hiss or fluff, especially important in the near silent scene in which Candy visits the location of her mother's death at night.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are also available.

Audio Commentary with Michael Brooke and Johnny Mains

A consistently chatty commentary by writer and film programmer (and occasional Cine Outsider fact corrector) Michael Brooke and author Johnny Mains, who examine a film they both clearly hold in high regard with infectious enthusiasm. While often screen specific, both deliver information at such a pace that they're able to also shoot off at logical tangents to comment in some detail on the actors, the director, the locations, possible influences on the content and style, the international variations on the title, the suspect nature of the relationship between Paul and Candy, and a good deal more. They also point out that Paul's opening murder wouldn't actually work because the rubber tubes connecting the snorkel to the outside are too long to allow a full intake of fresh air and a clear exhalation of carbon dioxide. They're right, of course, but I have to admit that I had presumed that Paul's reason for selecting a mask with dual vents was so that it could be fitted with valves that would allow air to be pulled in through one tube and exhaled through the other. Watching this sequence again, I was thus a little crestfallen by a camera angle that revealed this was almost definitely not the case.

Undercover Killer: Inside 'The Snorkel' (20:58)

Studies in Terror: Landmarks of Horror Cinema author Jonathan Rigby, BFI National Archive curator Josephine Botting and cultural historian John J. Johnston discuss the origins of the project, director Guy Green and writer Jimmy Sangster, the altered ending, and the role played by the poster of Jacques-Yves Cousteau's Oscar-winning documentary, The Silent World. The lion's share of the running time, however, is spent on the cast, from the lead players down to a number of key supporting roles.

Hammer's Women: Betta St John (10:23)

The venerable Kat Ellinger provides a typically well researched look at the life and career of actor Betta St John, who plays Candy's older companion Jean. Nice to be reminded that she was also in City of the Dead, which is something of a favourite here.

Peter Allchorne and Hugh Harlow remember 'The Snorkel' (7:48)

Two of the smaller players in the film's production – floor props chargehand Peter Allchorne and second assistant director Hugh Harlow – recall their experiences working on The Snorkel. Allchorne reveals that it was him under the sheet when Candy's mother's body is carried out to the ambulance, and Harlow remembers the experience of making the film as an enjoyable one.

Original Script Ending (9:58)

A re-edit of the final scenes to conform the film to co-screenwriter Jimmy Sangster's original ending. I can't really say any more without getting into serious spoiler territory.

Four-Note Fear (23:18)

David Huckvale, author of Hammer Film Scores and the Avant-Garde, outlines the career of composer Francis Chagrin and meticulously deconstructs his score for The Snorkel, playing themes on the piano which are mixed into film extracts and the orchestral score.

Theatrical Trailer (1:54)

The American trailer for the film. We know this from the description of teenage Candy as "a slick chick who knows he's guilty!" Excuse me?

Image Gallery

41 high resolution slides of promotional stills, literature and international posters.

Booklet

The 28-page booklet opens with the credits for the film, which is followed by a thoughtfully argued essay on The Snorkel by Kat Ellinger. After this, we have an extract from screenwriter Jimmy Sangster's memoir, Inside Hammer, in which he specifically discusses the film, including the ending as originally written. Finishing things up, we have extracts from three of the contemporary reviews, two of which are a little sniffy about the film. A number of promotional still have also been included.

| NEVER TAKE SWEETS FROM A STRANGER (1960) |

|

When it comes to foundations for feature film storytelling, there aren't many trickier than paedophilia. It's a subject that provokes extreme emotions, and in recent years has become the laziest way of casting a character as irredeemably evil. You want to create a violent antihero and keep the audience on his side even when he commits unspeakable acts? No problem, just have him kill a paedophile first, and most viewers will then go wherever you want to take them. But if you want to build a serious drama around the subject of paedophilia, then you'll find yourself walking a moral and ethical tightrope and running the risk of alienating viewers, even today. So, try to imagine how audiences must have reacted to Hammer's 1960 feature, Never Take Sweets from a Stranger, which tackles the subject with surprising directness.

The lovely voiced Patrick Allen plays Toronto-born Peter Carter, who as the film begins has recently arrived in a small Canadian town with his English wife Sally and nine-year-old daughter Jean to take up the position of principal of the local school. Jean has already made friends with 11-year-old Lucille, and when the two are playing on a woodland swing, Jean loses a purse containing the money she has saved for candy. Lucille tells her not to worry, as she knows where they can get sweets for free and leads her in the direction of the mansion home of the ageing Clarence Olderberry, Sr., who has been watching the girls intently from an upstairs window. That evening, during the course of seemingly innocent conversation with her parents, Jean reveals that Olderberry gave them sweets after they agreed to strip naked and dance for him.

Despite the hints dropped in that woodland swing scene and a title that was almost a mantra delivered by parents to their children when I was a wee lad, this moment still comes as a bit of a shock thanks to the frankness of Jean's words, her cheerful lack of realisation of what this implies and a welcome degree of cinematic restraint. Peter and Sally are understandably shocked, but while Sally is all for heading straight to the police, both Peter and his initially startled mother caution against it. "You must keep a sense of proportion," she tells Sally. "After all, Jean wasn't actually hurt," which seems to me to be missing the point. It's also she who brings up the potential impact that making such an accusation against a respected local figure might have on their own standing in a community in which they are outsiders.

When Jean has a nightmare about the old man, however, Peter heads straight to the office of local police chief, Captain Hammond, to report the incident, but when Sally follows this up the following morning, Hammond tries to dissuade the couple from proceeding with the complaint. Olderberry, it turns out, is widely respected for having transformed this once small community into the prosperous town it is today, and as a result the locals seem willing to turn a blind eye to any improprieties on his part. You can't always believe what kids tell you, Hammond assures Sally, but when she refuses to drop the charge, the influence and reach of the Olderberry clan soon makes itself felt. Jean is politely refused access to a friend's house, and when Peter and Sally approach Lucille's parents for support, they discover that Lucille has been sent away to stay with a relative, and that her father, who works at a mill owned by the Olderberry family, has no interest in becoming involved. Even when it is revealed that Olderberry spent some time in a sanatorium, Peter is unable to access information from the guardian of an institution that is kept in business partly through donations from – you've guessed it – the Olderberry family. The current head of the family businesses, Clarence Olderberry Jr, also tries to smooth things out with the Carters, but when they insist on moving ahead with the case, he angrily assures them that his father's legal representative will tear Jean to shreds on the witness stand.

Events move forward at an unexpectedly swift pace, and we're only 40 minutes in before the case comes to court, and just minutes later it seemed clear to me that this was where the rest of the film would be set. But things also do not play out as expected here, paving the way for a final act that moves the film into darker territory and a final turn of events I genuinely didn't expect a film of this age to follow through on so unflinchingly.

That the film was not a financial or critical success on its release is, in retrospect, not all that surprising. Precious few films from this period even obliquely broached the issue of paedophilia, and even fewer tackled it as directly as Never Take Sweets from a Stranger. In that respect, it's a film that feels ahead of its time and one that still packs an unexpectedly strong punch. That it also explores the way that wealth and influence can buy protection and silence makes its Blu-ray release feel uncannily timely, as the #MeToo movement has revealed that a whole string of once widely respected men have used their positions of power to sexually abuse others without fear of recrimination.

In spite of a title that clearly flags its central concern, I was seriously caught out by Never Take Sweets from a Stranger. It takes a soberly non-sensationalist approach to a still controversial subject, is tightly and purposefully directed by Cyril Frankel, boasts typically fine monochrome scope cinematography from Freddie Francis, and is compelling performed by an excellent cast, particularly young Janina Faye as Jean, Gwen Watford as her distraught mother and veteran actor Felix Aylmer as the creepily silent Clarence Olderberry Sr. It also makes thoughtful and effective use of the oft-maligned three-act structure and builds to a genuinely tense and ultimately chilling finale. It's a remarkable, intelligent and still-relevant social issue drama, one that's as far from the popular image of what constitutes a Hammer movie as you're likely to find.

A robust monochrome 2.35:1 transfer that's free of any jitter and clean of damage and dirt. The contrast is on the punchy side, and while the film is clearly lit with the intention of highlighting some elements and casting others into shadow, just occasionally this can feel as it's sucking in a detail in darker areas, particularly if a shot features black clothing and furniture, as with the opening wide shot of a scene set in the judge's chambers during the course of the trial. The black levels are inky, but the tonal range of the image is still good and the detail is sharp.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is once again clear within the expected range restrictions and is free of noise or damage.

Optional subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are once again available.

Alternate Versions

You have the option to watch the film either with the original British opening titles, or with the American title, Never Take Candy from a Stranger. In other respects, both versions are the same.

Conspiracy Theories: Inside 'Never Take Sweets from a Stranger' (24:36)

The same trio of interviewees from Undercover Killer examine the making of the film and provide details on the main cast members, director Cyril Frankel, cinematographer Freddie Francis and production designer Bernard Robinson. The themes of the film are explored, as is the reaction to it, and we're informed that studio head James Carreras later regretted having made the film. All three interviewees beg to differ with this opinion, with Jonathan Rigby describing it as "an extraordinarily powerful film," despite taking slight issue with an element of the final act which he argues (persuasively, as it happens) dilutes the seriousness of the original crime.

Hammer's Women: Gwen Watford (7:59)

Laura Mayne looks at the life and career of actor Gwen Watford, who plays Sally in the film, which Mayne regards as her standout role. Like the trio above, she holds the film in very high regard (at one point she describes it as "an amazing film"), but does have a slightly disconcerting (nervous) habit of suddenly exploding into a half-laugh that is instantly cut short, making me wonder if I was missing the humour of the discussion.

An Interview with Janina Faye (14:23)

Actor Janina Faye, who plays Jean, looks back at her time with Hammer, which began with a role in the seminal Dracula. She recalls being cast in the same role in The Pony Cart, the stage play on which the film was based, but being pulled at the last minute because she wasn't yet quite at the then stage-legal age of 12. She talks about her audition and Cyril Frankel's way of working with child actors, and remains very proud of a film she believes all kids should have been able to see on its release.

An Appreciation by Matthew Holness (11:52)

Actor and comedian Matthew Holness pays tribute to a film he regards as Hammer's greatest thriller, but feels is also so much more than that. He discusses the original play, the lead performances, the frightening but not sensationalised set-pieces, and suggests it's all the more disturbing for not giving what you might expect from a Hammer film.

The Perfect Horror Chord (43:10)

David Huckvale is back to provide interesting background information on composer Elisabeth Lutyens and to revealingly deconstruct her score for Never Take Sweets from a Stranger. But it doesn't end there (check the running time), as Huckvale then does likewise with a number of her other genre scores, including Paranoiac, The Earth Dies Screaming, Dr. Terror's House of Horrors, The Skull and The Psychopath. Fascinating stuff.

US Theatrical Trailer (2:29)

A sober trailer that, like the film, avoids over-sensationalising its subject matter and pushes it as a social drama "that every adult will want to see."

Brian Trenchard-Smith Trailer Commentary (3:21)

In an episode from Trailers from Hell, Drive Hard and BMX Bandits director Brian Trenchard-Smith talks about the film's then taboo subject matter, director Cyril Frankel's approach, the performances and the film's adult certification in the UK.

Advertising and Publicity Material

34 pages of HD publicity stills and posters.

Press Material

47 slides of scans from the official press book. There's some interesting stuff here, so it's handy that the pages are manually advanced.

Booklet

A beefy 40 pages here, which after the film credits gets going with an interesting new essay on the film by Julian Upton. Up next is Never Take Sweets from a Stranger: An Introduction, a brief but useful look at how Hammer went out of its way to reassure people that the film was taking a responsible attitude to its incendiary subject matter. Following this is a fascinating collection of extracts from correspondence between producer Anthony and the BBFC over their concerns about the content of the film. Finally, we have extracts from the promotional manual that accompanied its release that focussed on the main cast. Once again, the booklet is illustrated with promotional stills and posters.

| THE FULL TREATMENT (1960) |

|

As opening shots go, the one fronting Hammer's 1960 The Full Treatment is a seriously neat attention-grabber. As a jaunty jazz tune dances across the soundtrack, the camera pulls back from the vehicular dashboard speaker from which the music is emanating to reveal the aftermath of a head-on collision between a sports car and a lorry. The unconscious car driver's head has penetrated the windscreen, and as we're in the UK at this point we can see that the lorry is on the wrong side of the road. Luggage is strewn across the tarmac, and the car's female passenger has been thrown from the vehicle, on the back of which a "Just Married" sign has been tied. The crew of a passing fuel transport lorry stops to lend assistance, a vehicle whose side is adorned with a poster for Castrol Motor Oil that features an image of celebrated racing driver Alan Colby, the very individual at the wheel of the crashed car. How's that for a title sequence?

Cut to two years later and Alan and his Italian wife Denise arrive in the South of France for a belated honeymoon, and it quickly becomes clear that while he appears to have physically recovered, Alan is still suffering from the emotional effects of the crash. Encouraged by Denise to take the wheel of the car, the experience reduces him to a nervous wreck, and he can switch from cheerful friendliness to paranoid anger on the smallest provocation. Indeed, his regular outbursts of sullen unfriendliness or accusatory fury makes him almost impossible to sympathise with, partly because we've all known someone like that in real life and their behaviour is usually down to the fact that they are a dick. Perhaps because of this, I quickly lost patience with Alan and really felt for Denise, who just puts up with this crap and stands by him no matter what he throws at her. Now, I realise that none of this is the unfortunate Alan's fault, but the problem is that we've not had the chance to get to know the man that Denise fell in love with in the first place and instead are invited to bond with the hair-trigger ball of anger and suspicion that he has become. This probably wouldn't be such an issue if he didn't blow up at her every few minutes or there were even the remotest grounds for his explosive jealousy. Making matters worse is that the accident has also impacted on his libido, and just a whiff of sexual desire triggers in him an uncontrollable urge to inflict harm on his lovely and tolerant wife. Thus, one minute they're both getting cheerfully fresh in the shower, the next Denise is nursing a bruise on her neck after Alan has tried to throttle her.

Someone Alan gets instantly grumpy with almost as soon as they reach their hotel is the friendly David Prade, who invites them to a dinner party that Alan huffily declines and then later decides might do him some good to attend. When the inevitable happens and Alan blows up and storms out, Prade reveals to Denise that he is a psychiatrist and convinces her that he is in a position to aid Alan's recovery. He even has a practice in Harley Street in London that Alan can easily attend when he returns to the UK. But will Alan agree to seek treatment from a man he already very loudly suspects Denise of seeing behind his back, and if he does will Dr. Prade be able to get to the root of Alan's problem and effect a cure?

Intriguing? Perhaps a little, but my irritation at Alan's behaviour made it difficult for me to care that much whether he sought help or not, and by this point the repetitive and predictable nature of his outbursts was making the journey a bit of a slog. What keeps it interesting is the strong suspicion that Prade's intentions are far from pure and that he actually has his eyes on the lovely Denise, an idea planted very firmly in our heads by a shot of Prade watching Denise swimming nude through binoculars on whose lenses her image is reflected. And I may not be an expert in psychiatric treatment, but I would wager that some of Prade's techniques would get him struck off were the General Medical Council to get wind of what he was up to. Entertaining though some of this is, it also contributes to the film's unfortunate propensity for heavily telegraphing later plot twists, nullifying most of the intended surprises and breaking a golden thriller rule by playing largely to expectations instead of keeping the audience guessing.

So, a complete misfire, then? Not by any means. The guiding hand of director Val Guest – who the following year would deliver the science fiction masterpiece, The Day the Earth Caught Fire – ensures that these frustrations are balanced by a number of dramatic and cinematic pleasures. These range from the claustrophobic and almost expressionistic use of close-ups during the psychiatric sessions, to the extraordinary, borderline hallucinatory sequence in which Alan flees from Prade's party by jumping behind the wheel of a car he has until then been afraid to drive, in the process recapturing the thrill of the race by tearing down country roads and through the streets of a nearby town. Circumstances also ensure that we eventually find ourselves siding with Alan in spite of himself, and I was with him with him all the way as forces continued to work against him and even he began to have serious doubts about his sanity. And while it has been heavily signposted in advance – and I do mean heavily – the scene in which Alan has to face the prospect that he may have committed an unspeakable act has a brief moment of horror that really resonates later.

The performances are solid enough, with French actor Claude Dauphin walking a fine line between amiability and slightly suspect creepiness as Doctor Prade without every overplaying it, and Diane Cilento convincingly authentic as Denise in her devotion to a man that many would have quickly abandoned. I'll admit to being less captivated by Ronald Lewis as Alan, though as is pointed out in the extra features, he's hamstrung a little by the script and the frequency and suddenness of his mood changes. Repeatedly, he reminded me of Dana Andrews' portrayal of self-centred and self-destructive newspaperman Peter Stenning in The Day the Earth Caught Fire, but where the dialogue in that film crackled at every turn, here it feels more functional, despite its sometimes snappy delivery. And where Stenning undergoes a gradual, circumstance-triggered redemption, Alan remains a prisoner of his psychosis for a sizeable portion of the uncharacteristically long running time and doesn't really let us in until the later stages.

For me, at least, The Full Treatment is easily the least effective of the films in the new Hammer box set. Yet despite my reservations, there's still too much of interest here – in the ideas, in the way specific scenes play out, and in the flourishes of Guest's direction – for me to dismiss it or suggest for a moment that you give it a miss. For all its faults, it's absolutely worth seeing and others will doubtless get more out of it than I did. That said, if you're planning to get your hands on this box set and fancy binge-watching the movies, I'd consider running this one first, as for all its positive qualities, it really is overshadowed by its companions.

Another impressive 2.35:1 HD transfer, with punchy contrast, solid blacks and a few highlights that come within a whisper of burning out, but never do. The detail is once again crisply captured, and the film grain, though visible, is very fine here. There is some very minor flicker visible on clear skylines at times, but otherwise the image is in sparkling shape, with little trace of dust or former damage.

Once again, we have a Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack and it's well up to the standard of the other discs in this set, being clean of hiss and damage and boasting clear reproduction of dialogue, effects and music, within the expected range restrictions.

The expected optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are all present and correct.

Alternate Versions

You can elect to watch either the original UK version, titled The Full Treatment, or the American cut, Stop Me Before I Kill!. Despite having the more sensationalist title, the American version is shorter, following the complete removal of a scene in which there is brief female nudity. More on this below.

Mind Control: Inside 'The Full Treatment' (21:15)

Jonathan Rigby, Josephine Botting and John J. Johnston discuss what is good about The Full Treatment and what doesn't work so well, and opinion appears to be divided on a number of factors. There's some praise for the performances, although Rigby suggests leading man Ronald Lewis was hamstrung by a script that had him violently switching moods with comical frequency, and Botting describes Diane Cilento's role as "a thankless part." The clear telegraphing of later events also catches some flack, and it's hard to be sure if Rigby's comment that director Val Guest tackled provocative themes in a tabloid manner is meant as a criticism.

A Subject for Analysis (14:35)

Vic Pratt delivers an engaging look at the career of writer-turned director Val Guest, exploring aspects of The Full Treatment that he sees as characteristic of Guest, and touching on the cuts made for the American version, including Guest's sarcastic response to outrage at Diane Cilento's nude swimming scene.

Censored Scene (4:11)

The original cut of the bathroom sequence, in which Diane Cilento's nipples are visible and Alan tries to strangle Denise following an erotic encounter in the shower, is compared directly to the censored American cut, which removes almost the entire scene and as a result doesn't make any dramatic sense.

Theatrical Trailer (1:56)

This is actually the trailer for the American cut, the more luridly titled Stop Me Before I Kill!.

It's not particularly seductive, but the narrator assures us that, "For the first time a picture lays bare the mind of a man." For the first time, eh?

Advertising and Publicity Gallery

56 manually advanced pages of high definition publicity shots, posters and garishly coloured front-of-house stills.

Press Material

70 slides feature HD scans from the press books, including the unsubtly titled 'Exploitation Notes'.

Booklet

Another 40-page booklet, one whose opening essay on the film is by the venerable Kim Newman, which is followed by information on the cast culled from Hammer's own promotional manual for the film. Up next is an excerpt from a career-spanning interview with director Val Guest in which he talks about his unrealised project, The Rolls-Royce Story. This is coupled with an extract from his 2001 memoir, So You want to Be in Pictures? in which he reflects on the censorship issues he faced on The Full Treatment. After this, we have an oddity, an extract from the promotional manual that claims to have been written by George, the cat that Dr. Prade keeps as a pet, plus a news story featuring the very same feline. There are some entertaining excerpts from the press book suggesting how to promote the film, including the offer to let patrons return another night should they faint from shock whilst watching the film. Finally, we have two contemporary reviews of the film. The New York Times liked it, Monthly Film Bulletin did not. Promotional stills and credits for the film are also included.

Whenever I watch a film that is largely confined to single location, my first assumption is often that it's based on a stage play. In past years, feature films liked to differentiate themselves from television – which the makers of movies regarded as a threat – by going places with the characters and cameras that TV budgets and equipment just would not allow. Feature films based on TV plays and series, meanwhile, liked to open up the action from the studio confines of the original. But just occasionally, a film would recognise that this locational restriction is an essential part of what made the original TV or stage production so effective in the first place. A prime example of this is Sidney Lumet's 1957 film adaptation of Reginald Rose's television play, 12 Angry Men, in which the action is confined almost exclusively to a jury room as one man attempts to convince his peers that there is reasonable doubt in a case that they believe is cut and dried. You've all seen this, of course, and if not, I envy you, as you have one of the most electrifying first viewing experiences you will ever have still ahead of you.

It's a similar story with the Theatre 70 TV play The Gold Inside, written by Jacques Gillies and directed by Quentin Lawrence, which in 1961 was adapted into a feature film by screenwriters David T. Chantler and Lewis Greifer for Hammer. Quentin Lawrence was again on board as director, and wisely recognised that expanding on the play's single location would be detrimental to its effectiveness as a character-driven tension piece. Save for a handful of brief exterior shots, the whole film takes place inside the confines of a small-town bank. And it really is superb.

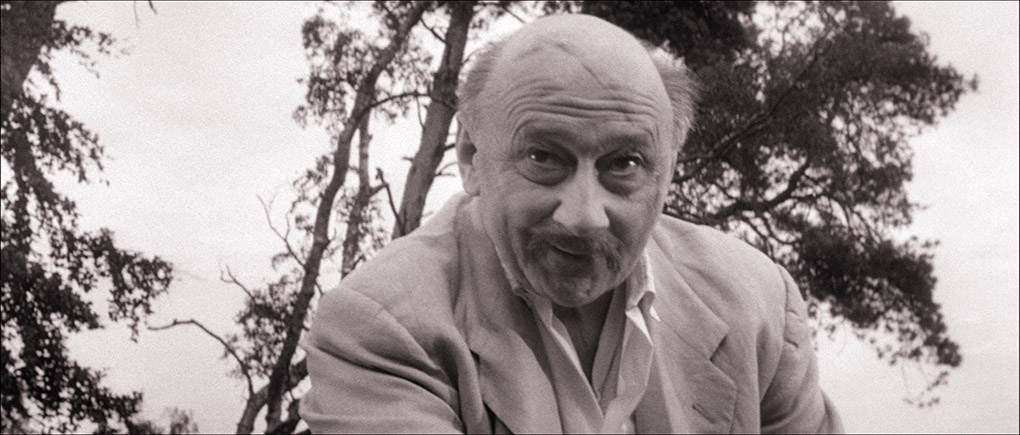

Peter Cushing is terrific and uncharacteristically unlikeable as overly prissy bank manager Harry Fordyce, a man whose obsession with order is captured economically on his arrival at the bank, where he checks the brass plate outside for scuff marks, makes minor adjustments to objects on the desk so that they are perfectly aligned, and ritualistically folds his scarf and places in over the shoulders of his meticulously hung overcoat. He's clearly a man with little joy in his life and an open contempt for the imperfections of his employees, particularly the put-upon Pearson (Richard Vernon, who also played this role in the TV original), whose attempt to cover up the mistake made by a colleague earns him a curt dressing down and the threat of termination.

A short while later, a cheerfully outgoing and well-dressed gentleman named Colonel Gore Hepburn (André Morell, also reviving his role from the TV version) arrives and asks to speak to Fordyce. On being shown into his office by Pearson, he reveals that he actually works for Home and Mercantile, the company with which the bank is insured, and is here to check up on their security arrangements. He adds to Pearson's gloom by chastising him for allowing such easy access to his manager's office, but on Pearson's departure, Fordyce receives a phone call from his wife begging him to do whatever this man says. A suddenly more sinister Hepburn cuts off the call and reveals that he intends to rob the downstairs vault of almost all of its cash, and that Fordyce's wife and child are being held by his men and will be made to suffer terribly if he fails to fully cooperate.

It's a very neat set-up that is then maximised by having events play out in real time and – a couple of short but crucial nips into the outside road aside – remaining confined to the bank interior, Fordyce's office and the vault below, creating a claustrophobic air of tension and placing the terrified Fordyce at the cocksure Hepburn's mercy. The film tasks a real chance here, playing out primarily as a two-hander in which the persecutor is a self-confident charmer and the victim is the most unlikeable person in the film. But the sharp interplay between Hepburn and Fordyce, riveting performances from Morel and Cushing, and Quentin Lawrence's tight direction keep the procedings consistently gripping. We're kept guessing about exactly how Hepburn's meticulously researched plan will play out, and as things come to a head, a potential complication is added when Pearson is advised by a colleague (familiar face Norman Bird) to check with Home and Mercantile's head office that Hepburn is the real deal, a move that has the potential to put Fordyce's family in jeopardy but which is repeatedly delayed by the plodding nature of the holiday season telephone network of the day. What really catches you out is the gradual revelation that this ingenious bank robbery caper is intertwined with elements of Dickens' A Christmas Carol, one that casts Fordyce as Scrooge, Pearson as Bob Cratchit and Hepburn as the Ghost of Christmas Present, an unexpected and frightening visitor whose actions help Fordyce to realise the error of his ways. It's no coincidence that the film is set on a snowy Christmas Eve.

Cash on Demand is a riveting example of Hammer at its non-horror best. The foundations are all there in Chantler and Greifer's tightly constructed screenplay, and director Quentin Lawrence works economical wonders with his small and interconnected locations and gets consistently fine performances from his excellent cast. It's an ingenious, gripping and intermittently nail-biting thriller, and a rare bank robbery tale in which there are no guns and whose only violence is a face slap delivered to bring Fordyce down to earth (itself preceded by a calm but intimidatingly firm request for him to remove his glasses). There's not a wasted moment in the whole film, and I loved every second of it.

A terrific 1.66:1 HD transfer, with generous contrast range, little evidence of any former dust or damage and a fine film grain visible throughout. Detail is very crisp, clearly capturing every bead of sweat on Cushing's terrified brow.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is again in fine shape, clearly reproducing the dialogue and effects and with no distracting hiss or fluff to spoil the tense moments of silence.

The expected optional English SDH subtitles are available.

Alternate Versions

When you select play on the menu, you are given the option of watching the original UK theatrical cut, which runs for an unusually brief 67 minutes, or the extended American cut, which includes 13 minutes of additional material and runs for 80 minutes. Time constraints have prevented me from making a side-by-side comparison as I've done it the past, but having watched the longer American cut, there's never a sense that it is padded or overlong, and it feels every bit as tight and economical as the UK original, only with a little more character interplay.

Audio Commentary with David Miller and Jonathan Rigby

Johnathan Rigby is here joined by The Complete Peter Cushing author David Miller, and the two provide a lively and enthrallingly detailed commentary on the film, the director, score composer Wilfred Josephs, the underlying themes, the original TV play, and the specifics of individual scenes. Unsurprisingly, there's plenty on the actors, with particular focus on Peter Cushing and André Morell, and the enthusiasm both have for the film comes through in spades.

The Perfect Crime: Inside 'Cash on Demand' (18:50)

The by now familiar trio of Rigby, Botting and Johnston offer up a detailed appreciation of the film, covering all the expected bases without feeling like they are re-treading point made on the commentary track. Rigby cements his enthusiasm for the movie by describing it as "a perfect little gem of a film."

Hammer's Women: Lois Daine (9:51)

In a break with the other Hammer's Women entries in this set, Becky Booth examines the career of actor Lois Daine in voice-over only from a pre-prepared script, which is illustrated with film extracts, still and graphics. The general perception of Hammer's women comes under interesting scrutiny, and Daine's other two films for the studio – Hell is a City and Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter – are given special attention.

Lois Daine on 'Cash on Demand' (7:36)

Actor Lois Daine recalls her first role for Hammer in Hell is a City and the chance meeting with Michael Carreras that landed her the role of officer junior Sally in Cash on Demand. She talks briefly about her fellow cast members, ponders on the difference between film and TV work, and remembers the making of the film as an enjoyable experience.

Theatrical Trailer (2:21)

A no-nonsense trailer with no serious spoilers, but still probably shouldn't be watched before the film itself.

Advertising and Publicity Gallery

53 slides of crisply rendered publicity photos, posters and horribly coloured front-of-house stills.

Press Material

35 slides feature scans from two press books, including a very impressive looking one with a golden cover and the original TV title of The Gold Inside.

Booklet

36 pages of handsomely printed goodness here, starting with credits for the film and a detailed and worthy essay on it by Kim Newman. An engaging interview with Peter Cushing from Hammer's publicity manual is followed by a profile from the same publication of director Quentin Lawrence, which focuses more on his background than his film career. The publicity material also provides us with profiles of actor André Morell and producer Michael Carreras, and the booklet ends with two contemporary reviews. Even Monthly Film Bulletin liked this one! Promotional stills and posters have also been included.

On the release of Indicator's first Hammer box set, Fear Warning, I was twitching with excitement at the prospect of a follow-up release, and Criminal Intent absolutely lives up to that sense of anticipation. Three terrific films and one interesting one (feel free to disagree), all in spanking new HD transfers and each with its own set of worthwhile extra features, including reversible covers for the individual Blu-ray cases. It's a marvellous set that should help to change the perception of Hammer as purely a producer of horror cinema and serves to showcase some of its best but lesser seen work of the late fifties and early 60s. It's a limited edition set, so get your order in now if you've not already bought it. Very highly recommended.

|