|

I’d love to tell you that when reviewing a film I remain completely neutral and am not in any way affected by personal preferences or prejudices, but I just can’t. If we’re being honest, none of us who chose to write about films can. It’s because of this that my fondness for Hammer movies of years past tends to be a little genre-specific, and while I’ve had a long-lasting love affair with the studio’s horror output, I’ve tended to be on the fence when it comes to its less widely discussed swashbuckling adventures. I didn’t see them in my youth and thus find it harder to put myself into the shoes of a 12-year-old me that may well have enjoyed them than someone like Hammer devotee Stephen Laws, who provides introductions for three of the four films in this latest Indicator box set. And as is pointed out by Kim Newman in a typically fine extra feature, there are elements in each of the titles here that make it just that little bit harder to retrospectively appreciate what makes them interesting as movies. But I’ve given it a go, and while I can’t ignore the aspects that have dated or that just don’t click for me, I found it easy to appreciate the things in each that are still worthy of praise.

The four films here are linked by their foreign locations, all of which were, of course, reproduced in and around Bray Studios in London. Visa to Canton is probably the odd one out, being the only one not directed by John Gilling (he of Plague of the Zombies and The Reptile) or featuring Oliver Reed in a key supporting role, the only one shot in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio rather than scope, and the only one set in the modern times of the day. All feature British actors in non-British roles, which is not a problem if it just involves speaking with a European accent, but not so great when Caucasian actors are unconvincingly made up to look Indian, Chinese of Afghani. And while allowances have to be made for the fact that these were different times, it’s hard to ignore that this is an aspect that has not aged at all well.

As ever, all four of the films have been presented on separate discs, each with it’s own comprehensive set of special features, and once again this is part of the reason this review is being delivered so late. Well, that and the disruption to life in general caused by a certain pandemic. Although I’ve covered each of the films and their special features separately, I’ve tried to rein it in a bit from the four-page monster that was my overlong review of Hammer Volume Four: Faces of Fear, and thus have kept it down to one, albeit lengthy page. I realise I keep changing the format of the Hammer box set reviews, but for this one I’m going back to the layout set in Hammer Volume Two: Criminal Intent, with each title covered in its entirety – film, technical specs and special features – before moving on to the next, with the films themselves listed in chronological order.

If you were writing a story in which a man is recruited by an American agency that is probably the CIA to embark on a potentially dangerous espionage mission, what profession would you have him working in to give the tale a degree of plausibility? I’m not going to offer my own suggestions here, but whatever you came up with I have a feeling that Hong Kong-based Travel Agent was not on your list, yet that’s the setup for this rarely mentioned and little-seen Hammer film from 1960. Of course, there has to be more to it than that, and we soon discover that Don Benton (Richard Basehart), the travel agent in question, fought the Japanese during World War II as a combat pilot and is being asked by the forthright Sam Johnson (Kevin Scott) and his boss Charles Orme (Alan Gifford) to help rescue a pilot whose aircraft may have been forced down somewhere on the Chinese mainland. For reasons neither operative seems willing to specify, the safe return of this man is of considerable importance and they’ve come to Benton less for his skills as a pilot than the fact that he’s lived in Hong Kong for years, speaks Mandarin and a little Malay, and is known to have a number of useful contacts in the region. In a move that surprises for the film but has echoes in the behaviour of American corporations today, Benton is not interested in assisting because he’s a businessman and likes to stay out of anything political that might “prejudice my relations with the Communist government, such as they are.”

This all changes when he visits the home of the Chinese family that took care of him during the war and has all but adopted him as a son, where he learns from matriarch Mao Tai Tai (Athene Seyler – I’ll have more to say about her in a minute) that the downed pilot in question is her eldest son Jimmy (played by the redoubtable Burt Kwouk). Word has reached her that his plane came down near the island of Chinan Fu near Canton, and after pledging to do what he can to help his adopted brother, Benton secures the assistance of a boatman and crew and heads towards the island by night. Some serious suspension of disbelief is required here, as Benton heads straight for the very riverside hut in which Jimmy is hiding with no foreknowledge of where he might actually be on the island, and they then escape in a slow-moving sampan that the Chinese soldiers who are shooting at them make no attempt to pursue.

Jimmy’s only been back home a few minutes when local police official Inspector Taylor (Hedger Wallace) turns up to take him into custody on a trumped-up charge of opium smuggling. When Benton goes to police headquarters to protest, he finds the Inspector in cahoots with Orme, who reveals that one of the passengers on the downed plane was a courier carrying secrets of vital importance to the West and that some suspicion remains regarding Jimmy’s role in this individual’s possible capture. Keen to clear Jimmy’s name, Benton offers to help but finds his services are no longer required, so he sets about making his own way to Canton in the hope of locating the missing courier.

It’s a solid enough setup for a modest little espionage thriller that starts well but never really gets up a serious head of steam, though it does have some unexpectedly intriguing elements, some of which have aged a lot better than others. It’s great, for example, to see so many genuinely Chinese faces in the supporting cast, but being a Hammer movie from the early 60s, the principal Chinese roles are played by Caucasian actors in unconvincing oriental makeup. A key offender here is Athene Seyler as Tai Tai, who looks like an English grandmother dressed up for a costume party and delivers lines in that particle-free “me Chinese” manner that nowadays feels uncomfortably stereotypical. Seyler is an actor I have a lot of time for (check out her delightful performance as Mrs. Karswell in Night of the Demon), but here I winced every time she made an appearance. Mind you, as Benton’s gangland contact Inono Kong, Vienna-born actor Eric Pohlmann is about as Chinese as Elmer Fudd, and no Hammer film set in lands afar would be complete without an ethnic role for Marne Maitland, who here plays one Benton’s local Chinese contacts. Balancing this out to some degree is a robust central performance from Richard Basehart as Benton and a generally likeable supporting cast, the most unexpectedly engaging member of which is Bernard Cribbins as Denton’s perennially concerned Portuguese contact Pereira, his underplayed accent having the authentic ring of a man who has been living abroad and speaking English as a foreign language for some time.

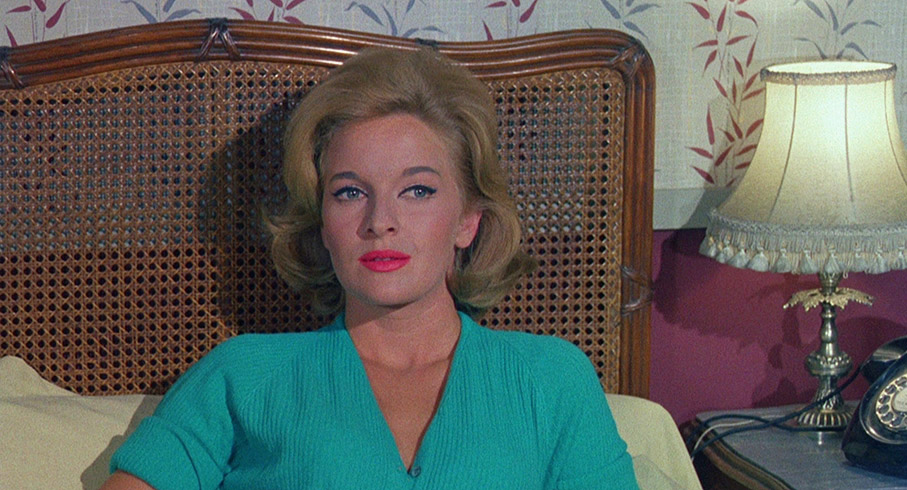

Where the film really intrigues is in the small but interesting ways it foreshadows the arrival of a certain series of celebrated (and still going) spy films whose lead character is famously licenced to kill. Obviously, as an unarmed amateur spy working independently of any government agency, Benton is no James Bond, but there are a handful of moments that have recognisable echoes in the early Bond movies, the most notable of which occurs when Benton walks into his Canton hotel room and the camera pans with him to reveal female courier Lola Sanchez (Lisa Gastoni) lounging seductively on his bed – all that’s missing is a wryly suggestive quip on Benton’s part. An even more striking moment occurs when Benton enters his office to the accompaniment of the very same rising three-bar music cue that concludes Monty Norman’s now universally famous James Bond Theme, which made its first appearance in Dr. No two years after the release of Visa to Canton. Read into that what you will.

I have to admit to never fully engaging with Visa to Canton, but I was also never remotely bored by it either. The action, when it comes, is a tad pedestrian, and the second-half double-dealing is not as gripping as probably it should have been, despite Lola’s engagingly self-confident sass and an unexpected (and distinctly Bond-like) late-story twist. Hammer bigwig Michael Carreras certainly doesn’t disgrace himself on his first directorial gig, one he took on at the last minute after original (also debut) director Don Sharp was forced to drop out, and he receives strong support here from cinematographer Arthur Grant and art director Bernard Robinson, both Hammer studio regulars. I wasn’t completely surprised by the news that it was originally planned as a pilot for a proposed TV series, and the ending certainly seems designed to suggest that more adventures involving Benton, his adopted family, Orme and the nervous Pereira were in the planning pipeline, but none ever appeared. In the end, moderate box-office ensured it was a one-off, but I can’t help suspecting that had it been released a couple of years later after the phenomenal success of Dr. No, it might have been a very different story.

Sourced from a Sony HD remaster, the 1.85:1 transfer here is in very good shape, with an attractive, pastel-leaning colour palette, a generous contrast range with solid blacks but no loss of detail in the darker areas (although Arthur Grant’s lighting ensures there are precious few of these), well-defined detail, a fine but visible film grain and no obvious signs of any former damage or dust. The quality of the image does ensure that the stock footage of Hong Kong stands out, having slightly softer detail, less pronounced contrast and a visibly coarser grain.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono track has a slight treble bias that feels about right for the period but is otherwise clear and free of background hiss and fluff, with solid reproduction of Edwin Astley’s score.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired have been included.

When you select Play from the main menu you are offered the option to watch the film either under the UK title of Visa to Canton or the American retitle Passport to China. As far as I’m aware, the only difference between them is the opening title sequence. More than one source (including the commentary track on this disc and Josephine Botting’s essay in the booklet) has claimed that the film was, somewhat mysteriously, released in America in black-and-white, at least on its first run, but the American version here is in full colour.

Audio Commentary with Kevin Lyons

Encyclopaedia of Fantastic Film and Television website editor Kevin Lyons once again lives up to his job title by providing biographies of all of the main cast members, director Michael Carreras, art director Bernard Robinson, screenwriter Gordon Wellseley, composer Edwin Astley and costume designer Molly Arbuthnot so detailed that they make up the vast majority of the commentary. He shares some interesting historical details about China’s ‘Four Pests’ campaign, which helps makes sense of a sequence in the film involving a sparrow slaughter celebration, and the real-life case of US Air Force pilot Francis Gary Powers, whose plane was downed in Soviet Russia, which is said to have been an influence on the story here. He also reads extracts from contemporary reviews, and reveals that the American release (retitled Passport to China, presumably because the distributor thought audiences wouldn’t know what a visa was or where Canton was located) was mysteriously released in black-and-white instead of the original’s colour, hence my comments in the Sound and Vision section.

Hammer’s Women: Lisa Gastoni (14:18)

Critic and writer Virginie Sélavy looks at the life and career of actor Lisa Gastoni, who plays Lola Sanchez in the film, outlining her early career and examining what makes her character in Visa to Canton interesting before exploring her later film roles, with particular emphasis on her co-starring role in the 1966 Italian crime drama, Wake Up and Die [Svegliati e uccidi].

Vic Pratt: Ticket to Ride (18:46)

A thoughtful and well-argued monologue from video producer Vic Pratt, who examines the xenophobic roots of the tradition for having foreign villains in popular fiction, and explores in fascinating detail the Hong Kong-set Hammer duo of Terror of the Tongs and Visa to Canton, with particular emphasis on their use of cultural and racial stereotypes and habit of casting white actors in Chinese roles. This is probably my favourite extra on this disc.

Bond Before Bond: Huckvale on Edwin Astley (14:28)

Indicator’s regular music commentator David Huckvale deconstructs some of the themes from Edwin Astley’s score in typically engaging fashion and educational detail, as well as highlighting elements that anticipate future film scores for James Bond and Pink Panther movies.

UK Theatrical Trailer (2:24)

“Journey into terror…and sudden death!” scream the screen-sized captions in an attempt to match the exited urgency of the narrator, who describes “Richard Basehart, travel agent,” as a “courier for trouble” and assures us that Lisa Gastoni is a “a girl with a passport marked ‘Danger’.” A seriously noisy sell that builds to a pitch of near-hysteria.

Image Gallery

58 screens of promotional photos, brightly coloured front-of-house stills, posters and scans from the film’s rather stylish press book, which was designed in the style of an old-school visa.

Booklet

As I mentioned above, each film in this set is treated a like a stand-alone release, with its own case, cover art and booklet. All four booklets kick off with the credits for the film before getting into the essays and other material and are illustrated with stills and publicity material, so take that as read in each case to save a little repetition on my part. First up here is a piece by BFI National Archive curator Josephine Botting, who highlights the positive aspects of the film without shying away from its more dated elements. Next is an extract from Hammer’s promotional publicity that draws parallels between the film and two then-recent real-life incidents involving American spy planes shot down over Soviet territory. Following this there are excerpts from Hammer’s publicity manual providing colourful biographies of the lead players for use in newspapers and fan magazines, and another with some factual background for the sparrow hunt in the film.

| THe PIRATES OF BLOOD RIVER (1962) |

|

Hmm. While I have to admit that The Pirates of Blood River is absolutely the sort of title that would have sold cinema tickets back in 1962, it also unwittingly acts as a potential spoiler for story developments to come. It’ll get into why with the appropriate warnings a little further down.

The film is set in the late eighteenth century on the isolated and uncharted Isle of Devon – which we can presume is somewhere in the tropics and not the county in which the world’s finest cider is brewed – where a group of Huguenots fleeing their homeland a century earlier chose to settle. The community leaders are now even more religiously devout than their pioneering ancestors, and they take a very dim view of anyone who breaks one of the Ten Commandments. Enter cheerful young Jonathon Standing (Kerwin Mathews), who is in love with pretty Maggie Mason (and uncredited Marie Devereux), but who has to sneak off into the woods with her to even grab a cuddle or a kiss or two. When the community elders, led by Jonathan’s sternly devout father Jason (Andrew Keir) catch them in the act, I thought I was in familiar territory. Clearly, I reasoned, the simple fact that they’re not yet married has upset the elders, or perhaps poor Maggie has already been promised to another by her father. As it happens, I was wrong. To my genuine surprise, the thing that has so outraged the elders is that Maggie is already married to one of them, Godfrey Mason (Jack Stewart), and despite the fact that she and Jonathan are in love and Godfrey is clearly a humourless git, they are both accused of transgressing the seventh commandment. Well, good for them, I say. Actually, it proves to be good for neither, as Jonathan is arrested and Maggie promptly flees and is chased into a river, where she is attacked an eaten by a shoal of hungry piranhas. Anyone see that coming?

The shaken Jonathan is put on trial and condemned to serve fifteen years in a hard labour penal colony from which few if any have ever returned. As he’s led away, he condemns the elders’ archaic religious beliefs and clearly has support for his views from a sizeable portion of the community, who are deeply unhappy with the court’s decision. By this point I was really warming to Jonathan, a progressive voice in a community governed by men with outmoded beliefs that they use to suppress freedoms and dissenting voices. Isn’t that why their ancestors fled France in the first place? Subsequent events suggest that this penal colony is located on a different island and seems to have been modelled on the one that Spartacus was condemned to (back-breaking quarry work with no clear final goal). The jailers, of course, are a sadistic bunch, and they know all about our Jonathan and thus take a special delight in making his life hell.

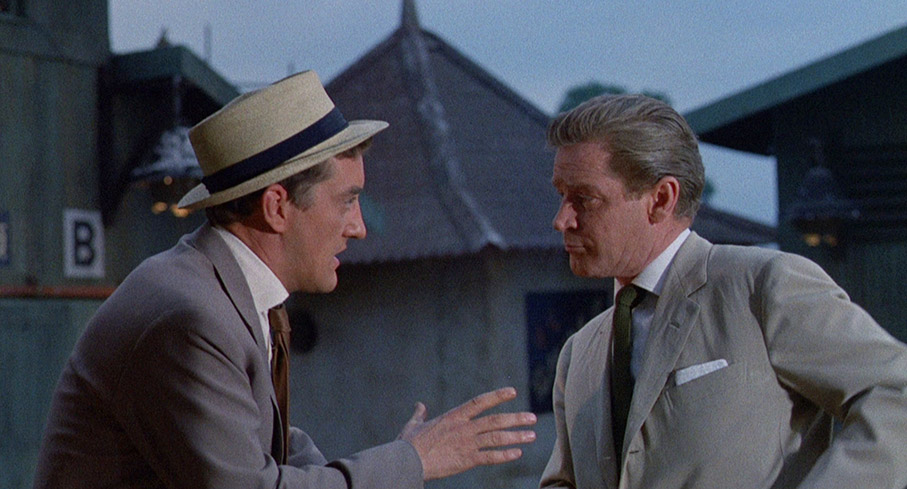

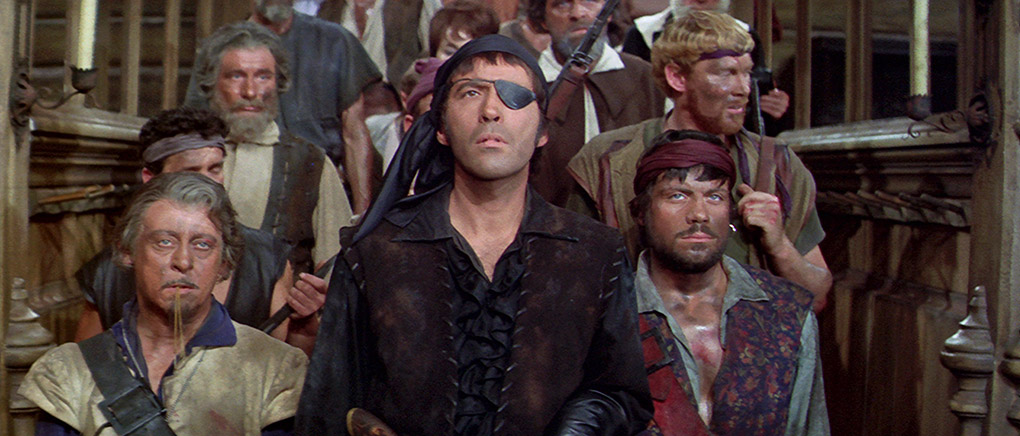

That Jonathan will turn on his tormentors and escape and ultimately end up in the hands of the pirates of the title is one of a number of predictable plot turns (though to be fair, that’s in part because they’ve been used so many times since, as well as before), but what did catch me out is that their leader, Captain LaRoche (Christopher Lee), despite sporting a regulation pirate eyepatch, is a thoughtful Frenchman who calmly questions Jonathan instead of threatening and interrogating him as expected. The pirates are a bit of a cultural mixed bag, with LaRoche and his two seconds, Hench (Peter Arne) and Brocaire (Oliver Reed!), all sporting reasonably convincing French accents, while second mate Mack (a very good Michael Ripper) is an old-school “Ah-harrr!” pirate of legend.

LaRoche somehow gets it into his head that there is a substantial treasure to be had from Devon, despite assurances from Jonathan about the simple life they lead. LaRoche and his crew thus make their way to the island, where they persuade the reluctant Jonathan to approach the community leaders with an ultimatum – let the pirates enter and search for this probably non-existent treasure and they won’t slaughter everyone in the settlement. Sound fair? The settlers’ response is to rashly open fire on the pirates and a battle between them ensues that is not destined to go well for a community that, we can presume, is not used to engaging in armed conflict with professional bandits. This lack of experience is reflected in the walls they have built to keep such enemies out, sensibly constructed of tall logs by the main gate but dropping down at one side to a height low enough for Jonathan to easily scramble over, which also provides a straightforward entry point for the pirates and makes you wonder why they bothered with such large and lockable gates at the front and back in the first place.

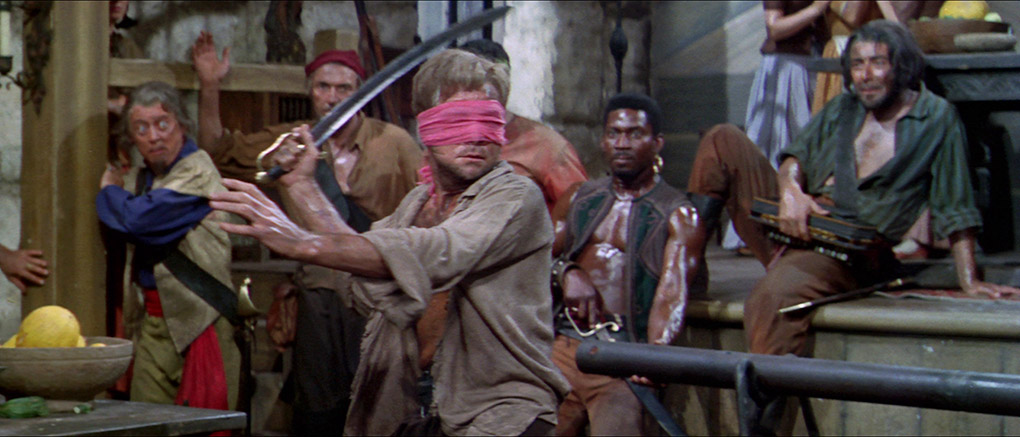

Captain Blood this is not and Kerwin Matthews is no Errol Flynn, but he’s likeable enough here and the film itself boasts a number of memorable and well-staged scenes. Jonathan’s prison camp suffering may push all the familiar buttons but it’s still effectively done, while the battle between the pirates and the settlers is excitingly paced, and a later matter-of-honour swordfight between Hench and Brocaire in which both men are blindfolded is a tensely-staged highlight, and all the more effective for being allowed to play out in unhurried real time. A later hit-and-run attack of the pirates is neatly staged, though I’m not sure I buy the effectiveness or even practicality of a second attack that requires the felling of a series of trees that then fall towards the pirate party, given how long each would take to cut down and a speed of descent that should give almost anyone the time they need to simply step out of the way. The development of the fractious relationship between Jonathan and his father is nicely done, as is the pirates’ growing sense of dissatisfaction with LaRoche, whose misguided sense of self-importance increasingly looks set to be his undoing.

Which brings me back to that title (skip ahead to the next paragraph to avoid spoilers), which for me signalled the likelihood of a later event that I presume was supposed to come as a surprise. Allow me to explain. If we assume that Blood River is the one in which poor Maggie becomes a piranha dinner (there’s certainly plenty of blood when they get stuck in) then we know that the pirates didn’t originate from there, despite the title linking them to it. So while they do cross that river to reach the Huguenot settlement without being molested by furious fish, Chekov’s Gun dictates that you don’t stage something as unexpected as a piranha attack at the start of your film unless it’s going to have a narrative pay-off later. That said, while these expectations were met almost on cue, they were still effectively played with, with the victims of this inevitable attack proving not to be the ones that I was still predicting they would be right up to the start of the scene in question.

The Pirates of Blood River is an enjoyable enough swashbuckling adventure that disguises its home county locations well, though as is pointed out by just about everyone in the extras, the water in the Black Park pond that stands in for the river of the title was so rank with effluent that it made several of the actors ill and left Oliver Reed with eye and ear infections. Director John Gilling does well by the action and handles the character scenes with brisk aplomb, and while the leads are engaging they’re given a run for their money by the supporting cast, with Reed in particular worth keeping an eye on even when at the back or the side of frame, and sharp-eyed viewers should be able to spot a young Dennis Waterman as one of the settlement children. It’s hard to deny that the film lacks the smartly choreographed swordplay, storytelling sweep and higher-budget spectacle of the better Hollywood swashbucklers, but it’s still an entertaining matinee adventure and for me probably the best film in this set.

A Sony HD remaster was the source for the 2.35:1 1080p transfer here. Contrast is nicely pitched with solid black levels in most scenes (a night-time campfire scene is spot-on), detail is crisp, and while there is a slight earthy hue to the colour palette in many scenes, the brighter colours are attractively rendered (the tapestry that hangs behind the statue in the main hall, the blood that so upset the British censor during the piranha attack). The image is largely clean, though some faint traces of former damage are just visible on a small number of shots. A very fine film grain is present, as expected.

The Linear PCM 1. mono track has clear reproduction of dialogue, and while the sound effects tend to lean towards the treble just a little, the music is pleasingly full-bodied in places.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are present.

Audio Commentary with Jimmy Sangster, Don Mingaye and Marcus Hearne

Presumably sourced from an earlier DVD release (two of the contributors have since passed away), this Marcus Hearne-hosted commentary with the film’s screenwriter Jimmy Sangster and art director Don Mingaye is a bit of a treat for fans of the film and Hammer devotees alike. Sangster reveals the origin of a project (a story you’ll hear repeated by others in the extras), talks about making the transition from production manager to screenwriter on X the Unknown, praises Michael Ripper and Christopher Lee, describes working for Hammer as akin to being part of a repertory company, confirms that the religious zealots are the real bad guys of the film and states matter-of-factly that the pirates “were just doing their job.” Mingaye outlines the job of the art director and explains in some detail how they sourced and created props for Hammer films, recalls first meeting Sangster on the aforementioned X the Unknown, reveals that he preferred making historical movies because of the research involved, explains how he created a Canadian police car for Cyril Frankel’s Never Take Sweets From a Stranger (a film both men have praise for), and that the falling trees in the film’s climax were made of polystyrene. Sangster also lives up to his reputation for being amusingly cynical, notably when Hearne remarks that director John Gilling made some excellent films, which prompts Sangster to interrupt with a deadpan, “Like which?” There’s lots more here, all of it enthralling.

Hammer’s Women: Marla Landi (11:10)

Favourite commentator Kat Ellinger takes a look at the life and career of actor Marla Landi, who plays Jonathan’s devoted sister Bess in the film, from her early work as one of the top international fashion models to her films for Hammer and her retirement to marry Sir Francis Dashwood, a direct descendant of the founder of the notorious Hellfire Club.

Introduction by Stephen Laws (11:34)

Unsurprisingly, Stephen Laws is a big fan of the film, but he also delivers plenty of information on its making, some of the key cast members and a couple of the more notable supporting players. Almost everything here also turns up in the other extras on this disc (the story about then BBFC chief John Trevelyan claiming this was the only film he recalls coming in as an ‘X’ and going out as a ‘U’ is in almost all of them), so how much you learn will depend on what order you watch the special features.

Archival Interview with Andrew Keir (20:16)

Recorded on VHS at the 4th Festival of Fantastic Films in Manchester in 1993, this on-stage interview with Hammer regular Andrew Keir, conducted by Stephen Laws (who nearly falls off the stage as soon as he sits down) has some audio issues but they’re absolutely worth tolerating for what Keir has to say. He reveals that he was a coal miner prior to becoming an actor, that the shooting of Quatermass and the Pit was “seven-and-a-half weeks of hell” thanks to director Roy Ward Baker, that he had all the time in the world for Hammer’s primo horror director Terence Fisher, and that his attempt to deliver a Latin blessing when staking Barbara Shelley in Dracula: Prince of Darkness repeatedly sent her into a fir of uncontrollable giggles.

Did I Write That?: Rigby on Sangster (42:27)

Although this goes for all of the interviewed experts in this set or on any other similarly feature release, there’s something a little awe-inspiring about watching someone like Studies in Terror: Landmarks of Horror Cinema author Jonathan Rigby spend 42 minutes recounting all of the key films and significant moments in the career of screenwriter Jimmy Sangster without a stumble or a pause to check his notes (I know it’s been edited, but still…). Having interviewed Sangster on several occasions he is able to quote his reaction to some of the titles, his most common response being a self-effacing, “Did I write that?” It’s as thorough an introduction to Sangster’s career as you could hope for, and makes for an excellent companion piece to Rigby’s near two-hour video interview with Sangster on Indicator’s previous Hammer box set, Hammer Volume Four: Faces of Fear.

Motifs of the Cheerful Heart: Huckvale on Hughes (8:20)

David Huckvale looks at the work of composer Gary Hughes and usefully deconstructs his score for The Pirates of Blood River. He also notes the influence of Erich Wolfgang Korngold on his work and tells a brief but amusing anecdote about the reputed rivalry between Korngold and fellow musical émigré Max Steiner.

Yes, We Have No Piranhas (10:37)

A welcome and well-assembled look at the cuts made to transform the ‘X’ certificate original into a more family-friendly ‘A’ certificate version, and then with further cuts and dialogue substitutions (no harlots or adulterers here!) into a ‘U’ certificate edit for a double-bill UK release with Ray Harryhausen’s Mysterious Island. It was a storming box-office success, but I’m glad we have the original cut on this disc.

Theatrical Trailer (2:02)

A lively trailer that moves at a lick and does a pretty good job of selling the film as a rip-roaring tale.

Brian Trenchard-Smith Trailer Commentary (2:18)

Filmmaker and regular Trailers From Hell contributor Brian Trenchard-Smith recalls seeing the film as a teenager on a double-bill with Ray Harryhausen’s Mysterious Island and being impressed by the amount of blood in the film. He notes that the film has dated but that for a wannabe 16-year-old filmmaker like himself it was inspiring.

Image Gallery

74 slides of promotional and production photos, shockingly coloured front-of-house stills, press book scans and posters.

Booklet

The lead essay here is by Senior Lecturer in Film at the University of East London Lindsay Hallam, who examines one of the few films to even touch on the violent history of the Huguenots with specific emphasis on the cast and the underlying themes. Next we have an always welcome extract from screenwriter Jimmy Sangster’s 2001 memoir Inside Hammer, in which he recalls the writing of his first “tits and swords” movie for Hammer, which includes two descriptive extracts from his script that are read out by Marcus Hearne in the commentary. After this there are excerpts from the pressbook and a variety of articles providing information on the cast members, often quotes from colleagues. There’s some really interesting stuff here, particularly Christopher Lee’s description of Oliver Reed, whom he befriended, as “thin, nervous and worried, muttering about leaving the industry and how he wasn’t cut out to be an actor.” Extracts from the US pressbook offering suggestions on how to promote the film include some suspect suggestions, my favourite being “If local pet shop can provide a tank containing piranhas, wonderful! Display ‘em in your lobby and take ‘em around to TV programs. Handle with care, of course.” Finally we have four extracts from contemporary reviews. None are exactly enthusiastic, with Monthly Film Bulletin dismissing the film as a “Stodgy, two-dimensional costume piece.” Ouch.

Three-and-a-half centuries after he died, there’s still some debate about whether Oliver Cromwell was a hero or a tyrant. In his favour is the fact that it’s largely because of the ousting of Charles I by Cromwell-led Roundheads during the English Civil War that we are governed by an elected parliament instead of a monarch. That said, I’m sure there are fair few out there who suspects that the ageing Liz Windsor could probably do a better job than the ropey collection of self-serving clowns who are currently mismanaging the biggest health crisis in our my lifetime. But Cromwell was also a religious nutball who believed he was God’s instrument on Earth and he attempted to wipe Irish Catholics from the face of the planet in a campaign that left over half a million dead. It’s a legacy that still angers the Irish to this day and understandably so – as recently as 1997, when the then Irish taoiseach Bertie Ahern met British foreign secretary Robin Cook in the latter’s private office, Ahern’s response to seeing a portrait of Cromwell hanging on the wall was to promptly walk out and refuse to return until the picture of “that murdering bastard” was removed.

The 1963 Hammer swashbuckler The Scarlet Blade nails its colours to the mast on this issue at the start with a caption that introduces us to “a band of freemen who defied a tyrant,” and in case you’re not sure who that tyrant is then don’t worry because he’s namechecked soon after. As troops scour the countryside rooting out traitors to the Cromwellian cause, a group of royalists led by Edward Beverley (Jack Hedley), soon to become the Scarlet Blade of the title, are attempting to smuggle the deposed king to safety. At the film’s start, he’s being hidden in the house of Edward’s father (John Stuart), but when news arrives that Roundhead commander Colonel Judd (Lionel Jeffries) and his men will be there within the hour, Edward and his men make moves to escort Charles to safety, wherever that may be. When his father insists that Edward take his brother Philip (Clifford Elkin) and sister Constance (Suzan Farmer) with him and announces that he’ll be staying put in an effort to delay Judd and his men, you’d have to be new to this movie thing not to immediately twig that he’s for the chop. It’s thus no surprise when Judd shows up at his door as predicted and, after failing to extract anything useful about the King’s whereabouts, calmly has Pa Beverley garrotted where he sits.

Eventually, Edward leaves the safety of the King in the hands of two of his most trusted men, unaware that their departure has been observed by a mercenary peasant who takes the information to Judd in the hope of receiving a reward. Want to guess how that goes? This allows Judd’s men to capture the King and his unfortunate escorts, and this, combined with the news of his father’s death, provokes Edward to launch a series of hit-and-run attacks on Judd’s patrols as The Scarlet Blade, which in turn makes his capture a priority task for Judd. The only thing is, with both Edward and Philip reported to have been killed in an earlier battle, the true identity and whereabouts of the mysterious Scarlet Blade is unknown. Matters are complicated further by fact that even after Judd and his men have moved in to the Beverley home, manservant Jacob (Harold Goldblatt) – whom Judd has mysteriously and short-sightedly retained – remains loyal to his former master and regularly sneaks off through a secret passage to provide Edward with information of the movement of Judd’s troops. Hot on his heels is Judd’s daughter Clare (June Thorburn), an unabashed royalist also looking to lend Edward a hand, which becomes a bit tricky when Judd’s no-nonsense second-in-command, Captain Tom Sylvester (Oliver Reed), falls for Clare and susses out what she is up to, but seems willing to take her side if she’ll look kindly on him

There seems little doubt that although heavily influenced by the Robin Hood story, The Scarlet Blade was subtly referencing The Scarlet Pimpernel with its title, just as the American retitle The Crimson Blade was probably hoping to stir memories of swashbuckling classic The Crimson Pirate. But the latter had Burt Lancaster and Nick Cravat at their most acrobatically engaging, and here the bad guys are way more interesting than the film’s dullard of a hero. As played by Jack Hedley, a fine actor in his own right who later shone as Lieutenant Colonel John Preston in the TV series Colditz, Edward is a well-meaning but uncharismatic rebel, someone you might follow because his policies were sound rather than because of anything about him as a person. As Colonel Judd, however, Lionel Jeffries, a later director of note who is largely remembered for his comedic roles, is a splendid ball of cold-hearted malevolence as Judd, and in one of his most substantial roles for Hammer, Oliver Reed puts his signature precision diction and cool stares to most effective use as Sylvester. This does mean, however, that once he claims, quite sincerely, that he’ll switch to the Royalist cause if that’s what it takes to get himself into Clare’s good books, it never seems likely that this is set to last – even when Sylvester is romancing Clare, there’s a strong sense that should she genuinely fall for him then he’ll likely treat her like crap and ultimately betray her.

The Scarlet Blade is a solidly executed historical action-drama and it's hard to pin down why I was never particularly excited by it. In the hands of director John Gilling it certainly moves at a lick, and the plot turns of Gilling’s own screenplay are adeptly handled, if rarely that surprising, though the arrival on the scene of the hard-nosed Major Bell (Duncan Lamont) nicely complicates matters for Sylvester and Clare. Jeffries and Reed definitely lead the acting honours, though Hammer regular Michael Ripper really throws himself into the role of Edward’s trustworthy gypsy companion Pablo. Once again, you’ll have to turn a blind eye to some discomforting brownface makeup, though as white actors made up as ethnic characters in Hammer movies go, it’s a lot less wince-inducing than some of the studio’s transgressions on this score, in part because of the focussed energy with which Ripper performs the role. Pablo is certainly one of the more potentially interesting characters in the film, the only one not fighting for one side or the other but out of his loyalty to his good friend Edward, at one point tellingly stating, “My people do not fight for a cause. They love no country. No country loves them.” Later, however, he’s given a line of his dialogue that aged less gracefully, when he tells Edward and Clare, whom he and his people have taken in and are hiding, “There are soldiers coming. Put mud on your faces. Whoever saw a gypsy with a clean face, huh?” Ah.

The fights are brisk and workmanlike and a fine period feel is created by Bernard Robinson’s art direction and Jack Asher’s cinematography, though the scale of a climactic battle between a band of Royalists led by Philip and a party of Cavalier soldiers is handicapped a tad by the film’s budget restrictions, with the fight itself having the feel of a vigorous rehearsal with too-little focus on the individuals involved. Better by far and for me the highlight of the film is a violent, vigorous and splendidly choreographed sequence in which Edward fights a Roundhead soldier in the confines of a small room using anything that comes to hand, as tense and inventive a scene as you’ll find anywhere in this set.

What did throw me a little was the finale (I’m avoiding specific plot spoilers, but feel free to hop ahead for safety). It scores points for a low-key exchange between three characters in which much is communicated through expressions alone, but also feels as if we’ve arrived at this point via a turn of events not shown in the film, while the ending is about as conclusive as the one for The Empire Strikes Back, but without the promise of a sequel to wrap up the loose ends. Then again, if the film was being true to history it would have to deal with the fact – only hinted at here though something Clare says to Philip – that Edward’s efforts to protect the King ultimately count for nothing, as Charles was eventually caught and tried for treason, and on 30 January 1649 was publicly beheaded. Apparently, members of the crowd dipped their handkerchiefs in his blood to keep as mementos. Now that would have been an ending to savour.

A clean and stable 2.35:1 transfer from a StudioCanal HD remaster with sharply rendered detail, well-balanced contrast when the light levels allow (day-for-night exterior footage is always a tough challenge) and a vibrant colour that never comes close to being over-saturated. A few tiny dust spots remain for the eagle-eyed in search of such things, but on the whole this is an impressive remaster that does Jack Asher’s lighting camerawork proud.

The linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack has some inevitable range restrictions but is otherwise clear and free of damage and background hiss or fluff. Bass-leaning sound effects (gunshots, drum rolls) have considerably more body than I would normally expect for a film of this vintage.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available.

When you select Play from the main menu you are presented with the option to play the film either under the UK title of The Scarlet Blade or the American retitle The Crimson Blade. Again, from what I can gather, the only difference between them is the opening title.

Audio Commentary with Kevin Lyons

Kevin Lyons kicks off another fact-packed commentary by expressing his bemusement at the American title change, only to later come to the same conclusion as I had about the reference to The Crimson Pirate. Damn, I thought I had one up on him for a moment there. As before, he provides a series of encyclopaedic biographies of all of the key cast members and many of those working behind the camera, including director John Gilling, cinematographer Jack Asher, production designer Bernard Robinson, composer Gary Hughes and special effects artist Les Bowie. He provides some useful information on the English Civil War for non-historically minded viewers (I had a close friend who was a member of the re-enactment society The Sealed Knot, so was regularly fed information on the topic), comments on the peculiar perspective of the first post-title shot (I knew something was bugging me about that) and notes that the way Oliver Reed and Lionel Jeffries play off each other is one of the joys of the film, a point on which we are in complete agreement. “Is it a great film?” he asks himself, then responding, “No, not really. But it is a good one.” Fair enough.

Hammer’s Women: June Thorburn (18:21)

BFI film curator Josephine Botting provides a meticulous, film-by-film breakdown of the career of actor June Thorburn, right up to her tragically young death and including details of her appearance on Desert Island Discs.

Introduction by Stephen Laws (6:41)

Stephen Laws discusses another of his childhood favourites, highlighting the work of Lionel Jeffries and his various often-forgotten villainous roles, Jack Asher’s colour cinematography, a particular scene involving Oliver Reed that to describe in any detail would act as a spoiler, and the film’s standout fight scene. The story he tells about Michael Ripper refusing to ride a horse is repeated several times elsewhere on this disc, a common feature of the extras in this set but inevitable when knowledgeable people are recorded separately.

Hugh Harlow & Pauline Wise: Doing Battle (7:12)

Second assistant director Hugh Harlow recalls shooting the scene in which first assistant director Douglas Hermes stepped in to stop director John Gilling from putting the life of the lead actor at risk, which prompted an argument that saw Hermes walk from the film and be replaced by a not completely comfortable Harlow. Wise meanwhile admits getting on well enough with Gilling despite noting that he could be difficult, and remembers a specific incident involving a farting horse. You read that right.

Kim Newman: Almost an Auteur (28:09)

I was really looking forward to watching this and it didn’t disappoint, as Newman examines the film career of director John Gilling in a manner that miraculously has little crossover with any of the other extras in this set. He highlights Gilling’s early work for Warwick films and teasingly suggests that had he not moved to Hammer he might have ended up directing one of the early James Bond features. He also reveals (I genuinely didn’t know this) that the British censor wouldn’t allow the names of notorious graverobbers Burke and Hare to be used in films until Gilling’s 1960 The Flesh and the Fiends and sings the praises of Gilling’s The Plague of the Zombies and especially The Reptile as two of Hammer’s finest. I’m with him on that. He examines all three of the Gilling-directed films in this set, which he neatly categorises as “matinee swashbucklers,” and notes that the casting of Caucasian actors in ethnic makeup does tend to undercut what’s fascinating about them, and it’s from this evaluation that the title of this review is adapted. There’s loads more here. An excellent extra.

Appropriately Military: Huckvale on Hughes (11:49)

David Huckvale delivers another of his insightful examinations and deconstructions of the film’s music score, this one by Gary Hughes. Here he highlights the influence of classical composers, the use of tritones (a term I’ve only become familiar with thanks to Huckvale’s contributions to Indicator discs), the use of military and mysterious themes, and more.

US Theatrical Trailer (2:30)

A smartly-assembled sell that time has almost completely drained of colour, though some still survives in the on-screen text.

Image Gallery

A whopping 110 screens of fabulous quality promotional and behind-the-scenes photos (a few of which betray the gender politics of the day – portraits of Oliver Reed and Lionel Jeffries feature them in their costumes, whilst Suzan Farmer is dressed in fishnet stockings and a black lacy corset), artificially coloured front-of-house stills, press book pages and international poster.

Booklet

First here is a fascinating examination of the film by Neil Sinyard, who identifies a possible link to David MacDonald’s 1953 film The Moonraker and even proposes the idea that the film is a partial prequel to Frederick Marryat’s 1847 novel The Children of the New Forest, from many of the main characters appear to have been lifted. Next Jeff Billington explores Oliver Reed’s film and television work in the 1960s, following which are a collection of extracts of writings about John Gilling drawn from various sources, including what is described as a “puff piece” from Hammer’s publicity material. In another choice slice from Hammer’s publicity cake, producer Anthony Nelson Keys reveals his fondness for American slang, and there are some amusingly tacky suggestions on how to sell the film from the Warner-Pathé pressbook – I did like the colouring-book picture of Oliver Reed and Lionel Jeffries. Bringing up the rear are extracts from two contemporary reviews, including an unusually positive one from Monthly Film Bulletin.

| THE BRIGAND OF KANDAHAR (1965) |

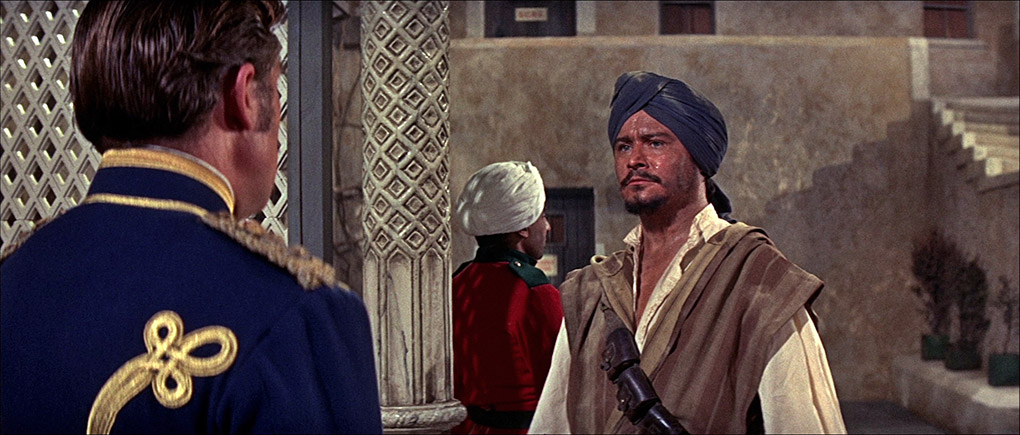

|

The Brigand of Kandahar is the sort of film that may have a fair few reaching for the reference books to make any real sense of. The title alone should trigger some head scratching, as while many will have heard of the Afghan city of Kandahar, I’m guessing that fewer are familiar with the term ‘brigand’. I had to look it up to confirm its meaning, and in case you are in the same boat, my Chambers Dictionary describes it as, “a bandit or highway robber, especially a member of a gang.” Then there’s the setting. Having become familiar with Kandahar through the various modern wars that have been fought on Afghan soil, I was then a tad confused by what seemed like the collision of Sikh and Muslim that sees some characters praising Allah whilst others are offered Rupees for information, which I was under the impression is the currency of India, Pakistan, Nepal and Sri Lanka. Any attempt to identify the race of characters by their facial characteristics is nullified by that fact that almost all of the non-white characters are played by Caucasian British actors in brownface makeup. I thus figured it was time to put down the dictionary and pick up the history books, where I was able to read about the Sikh invasion of Afghanistan, the occupation of Kandahar by British-led Indian forces and the jihad led against them by Sayed Din Mohammad Kandharai. Ah, it all starts to make sense now. Well, except for the fact that the film is set in 1850 and British forces withdrew from the city in 1842 and didn’t return until 1878, so weren’t actually present when the events depicted in this film take place. Then again, the fact that the starting location is named Fort Kandahar doesn’t mean it’s necessarily located in the city from which it takes its name, just somewhere, I gather, on the Northwest Frontier, which around that time could have included Kandahar, I guess. My head hurts.

For a British film in which British army officers play a prominent role, the Brits – or perhaps that should be the English – don’t exactly come out of it smelling of roses. The first of these unpleasantly scented individuals is Captain Boyd, who early in the film enters the chamber of Elsa, the wife of fellow officer, Captain Connelly, to follow through on an earlier ultimatum. Elsa has been having an affair with a certain Lieutenant Case and Boyd has ordered her to end it or has threatened to expose her, in part because he doesn’t like adulterous women, but mainly because Case is of mixed race and Boyd doesn’t think half-castes should even be allowed to join the British army, let alone sleep with white officer’s wives. What a toad. At the very moment this verbal confrontation is taking place, Case and Connelly are supposed to be on their way back from a secret sortie into enemy territory, but when Case returns alone he comes bearing the news that Connelly was captured and killed by feared Muslim warlord Eli Kahn. Boyd jumps at the chance to accuse Case of deserting his fellow officer, and a few whispers into the ear of fort commander Colonel Drewe sees Case arrested on a trumped-up charge of cowardice in the face of the enemy. A short while later he’s convicted, discharged from the army and sentenced to ten years in jail. He’s only been banged up for a few hours, however, when he’s freed by trusted Indian servant and Kahn loyalist Rattu, and in no time at all Case finds himself in Kahn’s company, where he is invited to join his previous enemy and fight against those who have wronged him.

In common with the two other John Gilling-directed films in this set, The Brigand of Kandahar looks good, moves at a lick, boasts strong performances and has an interesting, potentially progressive but ultimately conflicting subtext. Of course to get to what works you again have to deal with the decision to pass white British actors off as Indians and Afghanis by painting their skin brown, as if skin colour is the only thing that visually distinguishes one race from another. Thus the wily Rattu is played by Sean Lynch, Kahn’s sultry sister Ratina by Yvonne Romain, the mixed-race Case by Ronald Lewis and Kahn himself by none other than Oliver Reed, who gets to strip to the waist at one point to show just how much skin toner the production had managed to procure. While I can almost buy Lewis as Case (a child of mixed-race parentage will sometimes resemble one parent more than the other), Oliver Reed is about as Afghani as Winston Churchill and every bit as British, which is a shame because in all other respects he’s really good here, despite Reed’s later dismissal of the film as one of the worst he’s ever been in. I’m guessing the line of dialogue about Kahn having been educated in Britain was inserted to explain Reed’s typically precise English diction, and let’s not get started on Ratina’s clothing, styled in the fashions of 60s London and designed to accentuate her cleavage in a way that the clothing of Muslim women most definitely does not.

As I’ve said before, none of this was unusual in films of the day and was likely shaped as much by the perceived need to headline the cast with recognisable names as the pre-enlightenment racial attitudes of the day. Indeed, in its early scenes the film seems to be taking a firm stand against the racial prejudice of the British characters, particularly Captain Boyd (played by a suitably oily Inigo Jackson) and the complicit Colonel Drewe (Duncan Lamont). But once Case reluctantly joins up with Kahn it becomes increasingly uncertain whom we are supposedly to be rooting for. Certainly I was with Case when he swears vengeance on those who have falsely accused him, but as skirmishes are fought, prisoners are taken and Case becomes more resolute in his determination to punish the British, it becomes harder to engage with him as the victim of injustice that he begins the film as. As played by Oliver Reed, Kahn is enigmatic but ruthless and just a little egomaniacal, and it soon emerges that Ratina also has a lust for power and holds a grudge against Kahn for killing their brother, and is willing to double-cross him if Case will throw in with her. Kahn's and Ratina’s actions, meanwhile, serve to inflame the prejudices of the British officers, hardening them against the enemy and particularly Case, whom they now feel fully justified in labelling a traitor. And while Kahn’s treatment of prisoners is shown to be medievally cruel, the methods Drewe uses to frighten information from the locals could these days land him a job as a guard at Guantanamo Bay. Elsa, meanwhile, whom you might expect to stay loyal to Case, is disturbingly quick to believe he was responsible for her husband’s death, and any sympathy I initially had for her quickly evaporated. A traditional voice of reason in the shape of reporter Marriot (Glyn Houston) is introduced to point out the fault of both sides, but he shows up too late and is a little too po-faced and lacking in charisma to become the point of audience identification I presume he was intended to be.

This shifting sense of whom we are and aren’t expected to identify with hits a peak in the film’s final scenes (I’m going to avoid being too specific but if you want to keep things completely spoiler-free I’d hop to the next paragraph). Following a battle that leaves a character I’d lost sympathy with and one I’d never trusted both mortally wounded, they’re shown struggling to reach each other with a heartfelt desperation that would normally be reserved for sacrificial heroes, while British characters who were earlier portrayed as judgemental bigots are presented at the end in an almost positive light, despite some appropriately damning observations by Marriot.

The Brigand of Kandahar is one of Hammer’s odder adventures, starting as a progressive tale of bigotry and injustice and then seemingly unsure quite what it wants to say about either side of a situation in which almost nobody comes out smelling of roses. A history lesson it’s not, with historical fact little more than a jumping-off point for a diverting, briskly paced and intermittently entertaining boy's-own adventure tale, one whose stab at a spectacular climax is undermined a tad by an attempt to match visibly studio-shot combat shots with larger scale location outtakes from Terence Young’s 1956 Zarak, on which John Gilling was associate director.

Sourced from StudioCanal's HD remaster, the 2.35:1 1080p transfer here boasts punchy contrast with solid black levels and just a little less picture information in the shadows than you’ll find on the other transfers in this set. A slightly earthy hue to some scenes is balanced by the brighter colours on costumes and flags, and the image is largely clean and free of damage with a fine but visible film grain that coarsens just a tad on some shots and noticeably on the footage borrowed from Zarak.

The mono soundtrack is again reproduced as a Linear PCM 1.0 track and has the expected range restrictions and a slight treble bias to the dialogue, effects and music.

Again, there are optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired.

Audio Commentary with Vic Pratt

Video producer Vic Pratt provides a consistently interesting commentary on the film, its making and the personnel involved. He recalls first seeing it as a child, notes that it’s not a film beloved by Hammer aficionados and doesn’t shy away from the brownface issue, though does note that it was an accepted norm back when the film was made. We get biographies of John Gilling and several of the actors, including the “ravishing” Oliver Reed, who gets more coverage than anyone else here by a considerable margin and inevitably has some crossover with Kevin Lyons’ coverage of the same in his commentary on The Pirates of Blood River. I involuntarily pulled a face when Pratt admits to preferring Norman Wisdom films to Tony Hancock’s splendid The Rebel, but was right with him when he picked Ken Russell’s The Devils as Oliver Reed’s finest film.

Hammer’s Women: Yvonne Romain (7:39)

Melanie Williams provides some biographical details on actor Yvonne Romain and confirms that neither Romain nor Oliver Reed – whose final film this was for Hammer – wanted to make it. She signs off by dismissing it as “a piece of late-in-the-day colonial nonsense.”

Introduction by Stephen Laws (8:16)

Melanie Williams may be dismissive and the actors may not have positive memories of making it but you can rely on Hammer’s number one fan Stephen Laws to assure you that it’s actually a rollicking adventure tale, dismissing any criticism and all but instructing us to enjoy it. He has particular praise for Oliver Reed, though his claim that the actor is really enjoying himself in the role kicks against Vic Pratt’s somewhat less complimentary take on the same, and he ignores the costume incongruity to heap similar praise on Yvonne Romain.

Neil Sinyard: Adventures in Film (19:42)

The venerable Neil Sinyard here turns his attention to the career and reputation of director John Gilling, which he examines in enough detail to ensure that even if you’ve watched all of the extras on the previous discs, there’s still something new to absorb here. It makes for a fine companion to Kim Newman’s examination of the same on The Scarlet Blade disc.

Afghan Ostinati: Huckvale on Banks (12:43)

Here David Huckvale deconstructs the score for The Brigand of Kandahar by composer Don Banks, noting that his film music is atypical of the work he did outside of the movies and highlighting the influence of military marches here.

Theatrical Trailer (2:37)

Action sequences feature heavily in a trailer whose narrator clearly regards the character of Chase as a scoundrel and the beastly Colonel Drewe as a model of fine soldiery. Do me a favour.

Image Gallery

72 slides of crisp promotional photos, garishly coloured front-of-house stills and international posters.

Booklet

Leading the way here is an essay on the film by author Naman Ramachandran, who provides a clearer historical context for the film than my confused efforts, and examines the film in relation to other colonial films set in the North-West Frontier of undivided India and reveals, a little surprisingly, that most of the Hindustani dialogue heard in the Gilzhai camp is authentic and correctly pronounced. Hammer promotional material is back to provide biographies of the five principal actors in the film, complete with positive soundbites from the performers themselves, which is followed by another piece from the Hammer publicity machine, this one focussed on producer Anthony Nelson-Keys. Suggestions on how to promote the film from the British and American distributors include ideas for swordfights (!), spot-the-difference pictures and comic strips, giving you an idea of the age group the film was targeted at.

Four intriguing films with varying degrees of dated or problematic elements that I have little doubt some will absolutely relish, especially if you fell in love with them as a child as a couple of the contributors to the special features here clearly did. The fact that I wasn’t blown away by any of them is down in no small part to where my Hammer movie tastes lie and shouldn’t take away from the fact that all had elements to heartily recommend them. Even if I hadn’t particularly liked the films – and on the whole I did – I’d be championing this set anyway for making four little-seen movies by one of Britain’s most celebrated studios available with spanking transfers and more quality extras than you can shake a pikestaff at. Thus, while it’s not my favourite Indicator Hammer box set to date, it might well be yours, and it still comes warmly recommended.

|