|

I have to admit that when I first approached this second box set of Ray Harryhausen films from Indicator, I for some reason expected it to feel a little overshadowed by both its predecessor and the upcoming third collection. I soon realised that this dodgy misconception had grown primarily from the fact that while I know and love the films in the first and (especially) third sets, I'd previously seen none of the ones in this release. I should have had more faith. The set consists, after all, of two monster movies from the 1950s – a science fiction sub-genre that I have had a fondness for since I was knee-high to a vole – and a lively adaptation of Gulliver's Travels. What's not to love here? What caught me out was just how well they still play, something that no fan of Harryhausen's earlier Earth vs. the Flying Saucers – which I am – should have been even remotely surprised by. When I finished watching the three films, I was left wondering how and why I'd failed to catch any of them before, a small guilt trip that was tempered by the knowledge that I was seeing them for the first time looking better than they've looked since they first hit cinema screen back in the late 1950s.

I'll apologise up front for the late review. Covering a release with three fine films and packed with so many special features does take time, and it landed on my plate during what is proving to be one of the most difficult periods of my life so far, one that the magic of such films is doing its small but welcome bit to help me cope with.

And so to the films...

| It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955) |

|

American science fiction movies of the 1950s gave me some of my first serious film scares as a child, and were instrumental in triggering what quickly evolved into a love of cinema in general as I moved into my teens. And for my money, many of them still look terrific today. Sure, there have been great science fiction films since, but there's still something about the monochrome chills of 50s monster movies that remains unique to this golden period of American genre cinema.

If you've any doubt at all that It Came from Beneath the Sea is a 50s monster movie, you only need to take a second look at the title. Back in the 1950s, monster movies were a staple diet of drive-in theatres, and if you wanted to catch the attention of your potential audience you used the title to tell them in no uncertain terms just what they were in for, compressing the story into a short and sensationalist tabloid headline. It's a practice that fell out of favour in later years and is now largely confined to movies that deliberately trade on their cheapjack content. Which is why when Edward L. Cahn made a low-budget movie in 1958 about an alien creature stowing away about a spaceship and killing the crew members was titled It! The Terror from Beyond Space, and why the altogether classier partial 1979 remake wore the less explicit but somehow more suggestive moniker of Alien.

The use of the word 'It' in a title to suggest something inhuman certainly seems to have its foundation in 50s science fiction cinema with the likes of It Came from Outer Space, It Conquered the World and the aforementioned It! The Terror from Beyond Space (the term has recently made a made a bit of a comeback in the horror genre with the likes of It Follows and It Comes at Night). It Came from Beneath the Sea is very much a product of this illustrious cycle and gets off to a belter of a start, one that so clearly prefigures the opening of The Abyss that if James Cameron had genuinely never seen the earlier film before starting work on his movie, then it should be up for a coincidence award.

An American nuclear submarine captained by Commander Pete Mathews (Kenneth Tobey) is on manoeuvres in the Pacific when the crew detect a large and fast-moving shape on the sonar that appears to be following them and matching their speed. The subsequent collision disables the submarine, irradiating the interior and send it plummeting towards the ocean floor. Sound familiar? Where the two films part company is that here Commander Matthews and his crew are able to regain control of the vessel and return it to the surface, where a sizeable chunk of flesh from a large marine creature is discovered to be jammed inside the vessel's dive planes.

An investigation into the identity of this creature is then conducted by the marine biology team of Lesley Joyce (Faith Domergue) and John Carter (Donald Curtis), while Commander Pete hangs around asking questions and getting instantly captivated by Dr. Lesley's good looks. They eventually discover that the offcut is from the tentacle of a gigantic octopus, and when the creature attacks a ship and drags it under water, the Navy enlist Lesley and Carter's help to track it down and destroy it.

Okay, if there's one aspect of 50s monster movies that I've never been completely comfortable with it's the willingness of just about everyone to instantly label any errant creature as a threat and make immediate plans to blow it to smithereens. And while it's perhaps understandable that the Navy brass would be willing to do whatever it takes to protect commercial shipping and coastal communities, it's a little unsettling to watch two marine biologists go along with killing the creature without a serious word of protest about being given the chance to maybe study it first. Lesley even designs the missile they'll need to penetrate its head and blow it up remotely. What a noble contribution to the field of marine science and conservation.

In the extra features, Harryhausen talks about taking a documentary approach to the story, and while we're not talking the realism of United 93, there's still an authenticity to many scenes that is rare for 50s exploitation cinema and is a contributory factor to why the film has dated as well as it has. This is particularly evident in the opening scene, which was filmed aboard a real submarine and has a tangible sense of claustrophobia and a matter-of-factness that proves instantly involving, and is instrumental in selling the as-yet unidentified object approaching the submarine as a convincing threat. As so often with Schneer-Harryhausen productions, the story is solidly developed and the characters are engaging, and while the action occasionally has to be put on pause to accommodate the burgeoning romance between Pete and Lesley, even this is given an interesting edge by the teasingly unconfirmed nature of the bond between Lesley and her colleague John – more than once I was convinced that the two were actually a couple in an on-off relationship, and that John's professed encouragement for Lesley's involvement with Pete was making a sadness that she doesn't feel the same for him. Am I reading too much into this? That said, it's hard not to speculate a little about Lesley's past when she is able to switch from the slightly frosty scientist that Pete first tries to seduce to a flirty sexpot when the team needs to slyly persuade a reluctant male witness of a monster attack into revealing what he saw.

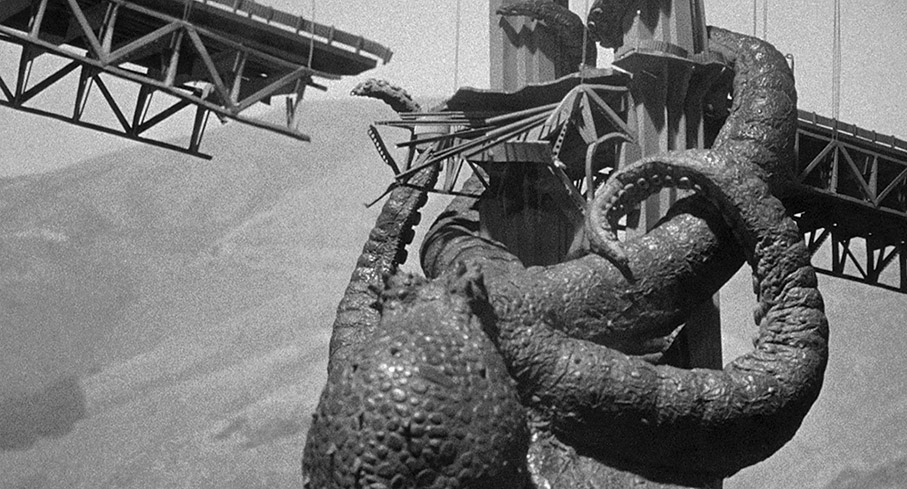

Of course, it's when the monster runs rampage that Harryhausen really gets to shine and the film moves into top gear. The Octopus itself is a splendid construction (the fact that, for reasons of economy and working speed, it his has six tentacles instead of eight is hardly an issue when you're talking about an atomic mutation) and is wonderfully animated, particularly when it begins tearing away at the San Francisco architecture, a most impressive melding of live-action and model work that peaks in a superb assault on the Golden Gate Bridge. And being briskly paced, solidly performed and decently scripted, there's never a lull between the special effects scenes. What more could you ask of a monster movie?

| 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957) |

|

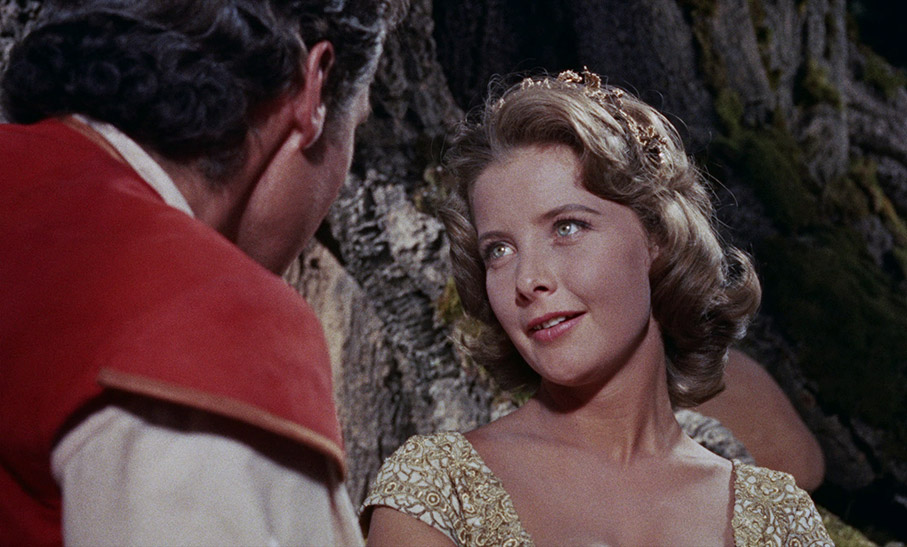

When an American Air Force spaceship crash lands into the waters just offshore of a small Sicilian village, local fishermen board it and rescue the only two survivors, one of whom dies just a short while later. While the locals discuss the need for medical help, young Pepe (Bart Braverman) discovers a cylinder bearing American Air Force markings lying in the water, inside of which is a large gelatinous and translucent pupa (a most convincingly gooey creation), which he hastily sells to local zoologist Dr. Leonardo (Frank Puglia) for the 200 lira he needs to buy a cowboy hat. Coincidentally, Leonardo is the very man the locals first approach to help the injured astronauts, not realising that a doctor of zoology is not a lot of use when it comes to medical matters. Bit of luck, then, that his attractive American daughter Marisa (Joan Taylor) is in her final year of medical school and able to lend the necessary hand. Leonardo is intrigued by the object he has almost absent-mindedly purchased, but a lot more so when it a small reptilian creature emerges from its confines. In no time at all it has doubled in size, and in the course of being transported to Rome by Leonardo to show to his colleagues, the now even larger creature breaks loose and escapes. In the meantime, a group of American military officials arrive at the village, and with the help of sole mission survivor, Colonel Robert Calder (William Hopper), begin a search for the creature they have brought to Earth.

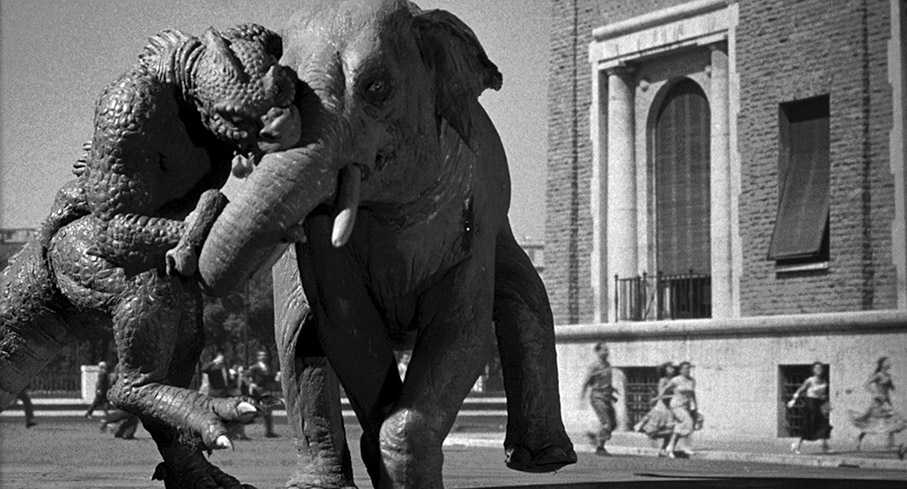

There are a number of elements here that will be familiar to any fan of 50s science fiction cinema, from the alien monster on the loose to the pretty young female doctor and good-looking male hero who initially bang heads but in no time at all are becoming an item. It all unfolds at a spanking pace and wastes little time on character building, casting almost everyone instead from ready-made molds and leaving us to get to know them on the move. It matters little, as they're essentially background detail to the main attraction and the prime reason for the film's inclusion in this box set, with Ray Harryhausen's creature design and animation stealing the show. The creature – which Harryhausen identifies on the extras as an Ymir, though it's never referred to as such in the film itself – is a wonderful creation, an upright walking reptilian humanoid with a lizard tale, beautifully animated and – small back-projection giveaways aside – most effectively matched with the live action footage. We even get treated to what was later to become a Harryhausen signature when the Ymir does battle with an elephant on the streets of Rome as terrified citizens scatter around them, a superbly handled sequence that for my money is up there with Harryhausen's best, though a fabulously staged and atmospherically lit encounter between the Ymir and its pursuers in a barn gives it a serious run for its money.

A couple of colourful Italian accents aside (one of the rescuers looks and sounds a little like one of the Super Mario Brothers), the performances are solid and the initially sparky relationship between Marisa and Calder is rather fun – "Well hello, almost-a-doctor," Calder says by way of contemptuous greeting when the two meet again after the Ymir escapes – even though we know they'll come to like and respect each other in the end. Director Nathan Juran – with whom Harryhausen would later work again on The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and The First Men in the Moon – makes great use of his Italian locations and keeps things moving at a breezy pace. The film even gets the jump on one of the most famous of all monster movies, with the creature's rapid growth from table-top curiosity to towering thunder lizard predating the alarming transformation undertaken by the title creature of Ridley Scott's Alien.

The only issue that I have with the film – and it's not really an issue if you view it as a tragedy rather than a traditional monster movie – is that Harryhausen's desire to make the creature sympathetic is so successful that I soon found myself empathising with it to the degree that I began to actively dislike its human pursuers, who make no real attempt to communicate with it and instead put all their efforts into hunting it down and destroying it. Now I'm fully aware that this is the main thrust of just about every 50s monster movie you might care to name, but the Ymir really is the victim here, a creature whose every act of violence is the result of provocation by man and beast alike. Think about it for a second (and there are spoilers ahead – skip the rest of this paragraph if you want to go in cold) – the Ymir is kidnapped from its home planet of Venus whilst in an embryonic state, slapped into a cage, attacked by a dog, cornered in a barn where it is shot at and a pitchfork is thrust into its back, hunted down with helicopters, trapped in a steel net and electrocuted into unconsciousness, clamped to a table to be experimented on, charged at by an angry elephant, and repeatedly shot at with canons and bazookas. And Colonel Calder and his boys wonder why it's angrily lashing out. As we hit the climax and the Ymir climbs the walls of the Colosseum in Rome and the might of the military is unleashed against it, the influence of King Kong is keenly felt. By then I had lost all sympathy for the humans and was screaming at the TV for this heavily armed and gung-ho collective to just leave the poor creature alone.

| The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960) |

|

I'd be willing to wager that when most people hear the title Gulliver's Travels they think of Lilliput and its six-inch-high occupants, a land in which the eponymous Gulliver is a giant. But as those familiar with Irish author Jonathan Swift's 1726 novel will recall, Lilliput is just the first of four very different destinations visited by Lemuel Gulliver, hence the book's exhaustingly literal original title, Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships. On the second journey, he winds up in Brobdingnag, where the size disparity he experienced in Lilliput is reversed and he finds himself dwarfed in a land inhabitant by giants. On the third he visits number of locations, including the flying island of Laputa, which was the inspiration for Miyazaki Hayao's 1986 animated feature, Laputa: Castle in the Sky. The least known and most blatantly allegorical adventure is his voyage to the Land of the Houyhnhnms, where a race of deformed, savage and disgusting humanoids known as Yahoos (this, we are assured, is where the word 'Yahoo' originated) are ruled over by more sophisticated talking horses, a representation of humankind at its best and worst.

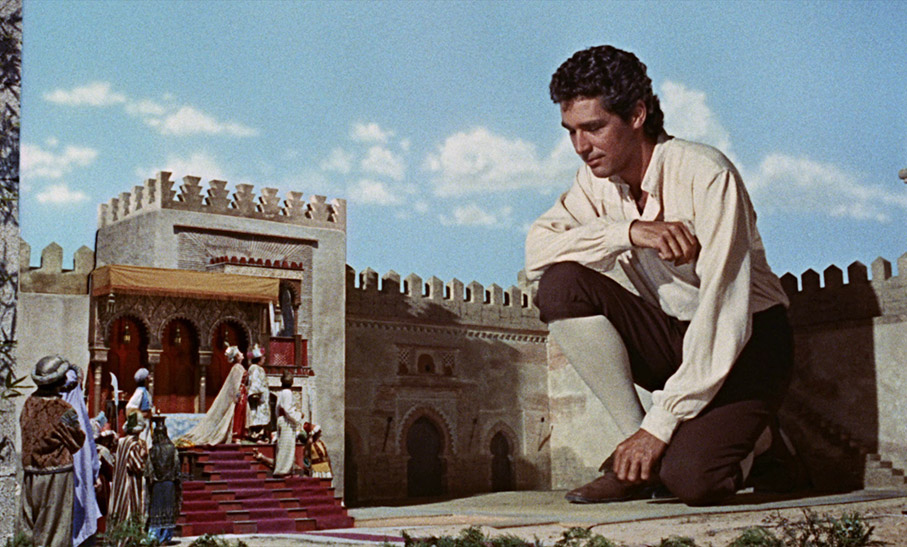

A film wearing the title The 3 Worlds of Gulliver may seem to promise that it intends to cover three of these voyages, but to make that assumption would be to forget the world in which Gulliver lives before he set out on his adventures. This is old-world Wapping – which has been curiously moved from London's Docklands to somewhere on the coast – when such locations tend to be pictured as storybook villages instead the glum urban sprawl they would later become. As he was in the source material, Lemuel Gulliver (played by Kerwin Mathews, who was later to take the title role in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad) is a local doctor who joins a ship as its surgeon, but in this adaptation has to first contend with his girlfriend Elizabeth (June Thorburn), who is firmly against such a venture and is busy making plans for them to set up home in a run-down house that they can't afford, thanks primarily to patients who pay their medical bills with cabbages and chickens. It's all too much for the ambitious Gulliver, which prompts a bust-up with Elizabeth that continues after he joins a ship that she stows away on. Their bickering follows them on deck, where a wave knocks Gulliver into the sea. He washes up on the shore of Lilliput, a giant in a land of tiny people who initially pin him to the ground with ropes, but eventually free him and allow him to build a boat and scoff the same amount of food as 1,728 locals in exchange for his help in dealing with their bitter enemy, the neighbouring country of Blefuscu.

It's in the absurd nature of the conflict between these two kingdoms that the satire of Swift's original first becomes evident, based as it is on nothing more than a disagreement about which end of an egg you should crack in order to open it. The social commentary doesn't stop there. In a gentle critique of the sort of bigotry that is still running rife on both sides of the Atlantic, Gulliver attempts to quell the concerns of the Emperor of Lilliput (Basil Sydney) by calmly assuring him, "I'm not an enemy, I'm only different," to which the Emperor tellingly replies, "That's the same thing, Gulliver." Later, the Emperor says to Gulliver, "Of course I don't need a prime minister to fight a war, but I need one to blame in case we lose it." And in a twist that couldn't help but make me think of the petulant and self-centred behaviour of a certain Donald Trump, it's only when the Emperor believes that Gulliver is becoming more popular than him that he turns against him.

When Gulliver arrives at Brobdingnag, their rulers prove to be no better, with King Brob (Grégoire Aslan) adding Gulliver to his collection of miniature animals and providing him with what is essentially a doll's house in which to live. In what has to be the film's most unlikely coincidence, Elizabeth has also fallen into Brobdingnag hands, and is soon suggesting that they set up home there instead – "It's a paradise compared to Wapping," she proclaims. I'm saying nothing. Gulliver, however, has other things on his mind, and when Elizabeth rejects his enthusiastic snog on the basis that they are not yet married, he promptly asks Glumdalclitch (Sherri Alberoni) – the young girl who first found him and has been charged with his care – to wake the King in order that he marry them so that that he can get his end away. King Brob happily obliges and appears to have a genuine soft spot for Gulliver ("I like little men with spunk!" he cheerfully proclaims in a line that hasn't dated as innocently as it was intended), but is being poisoned against him by Makovan (Charles Lloyd Pack), the scheming court physician whose poisonous daughter Shrike (Waveney Lee) appears to revel in the prospect of causing Gulliver harm.

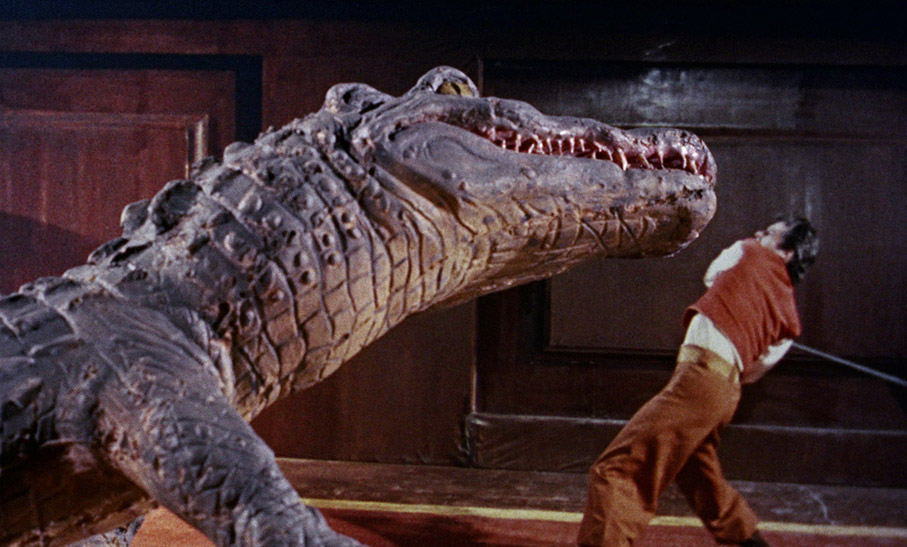

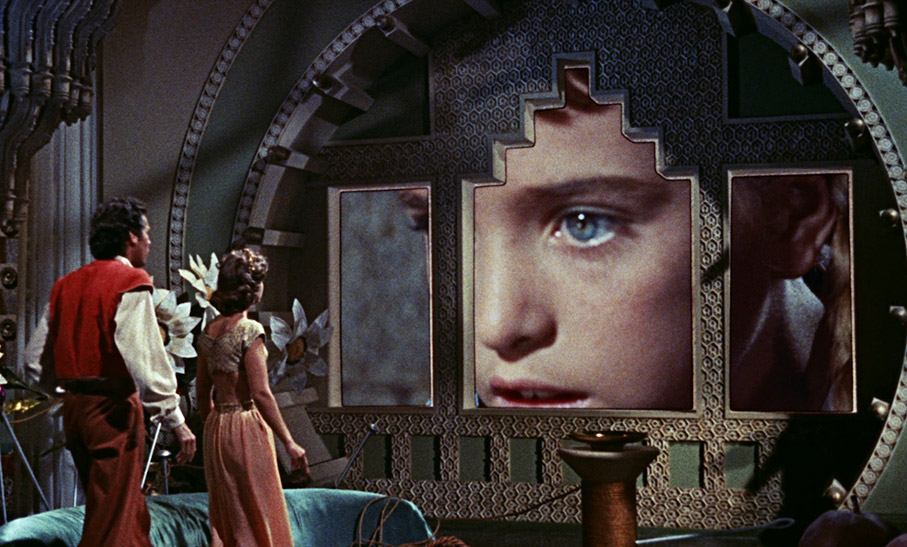

In one key respect, The 3 Worlds of Gulliver differs from the other films in this and the other Ray Harryhausen box sets from Indicator, whose key selling point is Harryhausen's creature design and showpiece animation. Here there are only two such scenes, and you'll have to wait over an hour for the first one and the showpiece sequence doesn't appear until 10 minutes from the end. The good news is that it's an absolute corker, with Gulliver doing battle with an alligator for the amusement of a group of oversized onlookers, armed only with a handily sword-shaped jewellery box clasp. What's showcased more in this film is photographic aspect of the Super Dynamation process, with a combination of travelling mattes and forced perspective photography used to convince us that people of vastly different size are interacting with each other. The mechanics of the process are intermittently visible, but so perfectly judged are the camera angles (those of giant stature are shot low and in close or mid-shot, while the smaller souls are often observed from up high and photographed wide), so accurate the eye-lines, and so energetic the storytelling, that the size mismatch is always convincing.

Deftly scripted by Arthur Ross and Jack Sher (I was repeatedly caught out by the smartness of the dialogue), it boasts an absolutely glorious score from Harryhausen regular Bernard Herrmann, one whose rousing main theme propels you headlong into the film and whose full orchestral sweep intermittently gives way to Herrmann's signature ominous bass notes and even elements that border on the avant-garde (an abrasive, rhythmic trumpet motif in the climactic chase prefigures one employed more aggressively by John Corigliano in Altered States). The result may cheerfully deviate from Swift's original (then again, the method employed by Gulliver to put out a fire in the novel would not have made its way into any film made back in 1960), but this is still a smartly made and hugely enjoyable fantasy adventure, and one of those rare films that has what it takes to delight adults and children alike.

Not only do you get the original monochrome versions of It Came from Beneath the Sea and 20 Million Miles to Earth, but also the later colourised editions, which you can select from the main menu or switch between using the Angle button on your player remote. Now I should state up front that Harryhausen himself, having originally wanted to shoot the films in colour, takes every opportunity in the extra features to express how happy he is with the results of this colourisation process. And far be it for me to disagree with the master, but if a film was shot in black-and-white, then as far as I'm concerned that's how it should be seen.

My fondness for the monochrome eeriness of 50s science fiction titles notwithstanding, the discipline of lighting for colour film is different from that of monochrome stock, and colouring in a black-and-white film at a later date always tends to look a little unnatural at best, and at worst resembles those coloured-in lobby cards that you'll find in the galleries on the extra features of this very box set. I'll freely admit that there are a few shots where the colour is not at all bad, but to often I found myself wincing at the result, and do a side-by-side comparison with the Eastmancolor glory of The 3 Worlds of Gulliver and the deficiencies of the process become all too apparent. So, embrace the colourised version if you prefer (and from a completist viewpoint, it's nice to see both versions included in this set), but I'll go with the black-and-white originals every time, thank you.

It Came from Beneath the Sea arrives in a 1.85:1 HD restoration from Sony that shines in the crispness of its detail, though this does render the slightly softer incorporated stock footage more visible. The contrast is very well balanced and retains solid black levels at all times without punishing shadow detail, and while a few minor dust spots remain, the print is largely clean and betrays no damage. A fine film grain is visible throughout.

The original mono soundtrack is available as a Linear PCM 1.0 track and is both clean and clear, but also included is a 5.1 remix, which sonically has the edge and even has some detectable stereo separation and the occasional sound effect whispering at the rear.

The 1.85:1 transfer of 20 Million Miles to Earth has also been sourced from a Sony HD restoration and boasts punchier contrast than It Came from Beneath the Sea, a few more visible dust spots, slightly coarser grain and the odd bit of flickering, but otherwise is in similarly fine shape, with a very impressive level of detail that really showcases Harryhausen's creature design and animation. The occasional use of stock footage is generally well integrated, though the helicopter that changes its markings midway through a scene is a bit of a giveaway.

Once again you can choose between the original mono as a Linear PCM 1.0 track or a 5.1 remix, which is slightly subtler in its rendition of dialogue and has some separation and slightly better bass. Both tracks are clear and free of damage.

The 3 Worlds of Gulliver is presented in a vibrant 1.66:1 transfer from a 4K restoration by Sony, with the sort of fine definition and crisp detail that really flatters the costumes and production design, though it does sometimes expose the workings of the matting process when the foreground is noticeably crisper than the projected background. Like I care about that. The colour is rich and pleasing in a way that the colourised versions of the other two films are not, and the print is impressively clean of dust and damage. A fine film grain is still visible, as it should be.

The Linear PCM mono 1.0 soundtrack is in very good shape, with clear dialogue rendition and no background his or crackle, and Bernard Herrmann's brilliant score sounds terrific throughout.

IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA

Audio Commentary

Arnold Kunert is joined by Ray Harryhausen and visual effects supervisors Randall William Cooke and John Bruno for a lively and appreciative discussion on the making of the film, with Harryhausen regularly pressed for details on how the effects were created and for background on the shoot itself. I was surprised that the guerrilla tactics they had to employ to photograph the Golden Gate Bridge for background plates when official permission was denied wasn't covered in the sort of detail it was in the BFI interview on Indicator's The Sinbad Trilogy set, but in other respects this delivers all the hoped-for goods, even if they do all keep praising the colourisation.

Tidal Wave of Terror! Joe Dante on 'It Came from Beneath the Sea' (7:40)

The always entertaining Joe Dante recalls first seeing It Came from Beneath the Sea and talks a bit about leading man Kenneth Tobey, who he later hired to play a small role in The Howling.

Remembering 'It Came from Beneath the Sea' (21:45)

Ray Harryhausen recalls his first meeting with soon-to-be regular producer Charles H. Schneer and provides some fascinating detail about the technical aspects of his work on the film, as well as revealing why his octopus has only six legs and that, with no books on stop-motion available at the time, they had to invent new techniques through a process of trial and error.

Tim Burton Sits Down with Ray Harryhausen (27:10)

Ray Harryhausen sits down with a hugely enthusiastic Tim Burton for an engaging chat about his work and a number of his films, including Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, 20 Million Miles to Earth and Jason and the Argonauts. There is some crossover here with other extras in this set (the colourisation process crops up just about everywhere), but the friendly nature of the chat is infectious and some of Burton's questions and observations pick up on points that are not covered elsewhere.

A Present-Day Look at Stop Motion (11:38)

New York University student Kyle Anderson delivers an outline of the techniques and processes involved in creating stop-motion animation. It's a little unpolished, and the background music is cheesy, but if you've never had a go at stop-motion yourself (and while time-consuming, it is great fun) then this is a useful introduction.

Original Ad Artwork (17:52)

How many discs in your collection have a gallery of promotional artwork and/or extracts from press books for the films in question? How refreshing it thus is to have this material presented and explained to us by someone who clearly knows and has a real affection for this material, something producer Arnold Kunert does with engaging aplomb. I really enjoyed this.

It Came from Beneath the Sea Again

A selection of slides depicting pages from a forthcoming comic book sequel to the film, with each page also enlarged to allow you to better appreciate the artwork and more clearly read the text.

Theatrical Trailer (2:03)

A wonderfully sensationalist trailer that's happy to reveal what happens at the climax and warns that "A tidal wave of terror engulfs the screen as a raging monster from the dawn of creation attacks the world of man!" Were giant octopuses around at the dawn of creation?

Ernest Dickerson Trailer Commentary (2:31)

Director Ernest Dickerson comments on the trailer for what he believes is the first film he ever saw and one that "scared the bejesus" out of him. Made for the Trailers from Hell series.

Image Gallery

23 slides of promotional material, including a few posters.

20 MILLION MILES TO EARTH

Audio Commentary

A satellite link-up allows the London-based Ray Harryhausen to participate live in a commentary with Arnold Kanert, Dennis Muren and visual effects whizz Phil Tippett in Berkley, California. Kanert, Muren and Tippett are all enthusiasts for the film and there is thus plenty of lively discussion on individual scenes, the filmmakers and the performers, and they take every opportunity to grill Harryhausen on the technical aspects of his work on the film. Subjects covered include Harryhausen's working methods (he preferred to work alone and didn't like visitors), the design and construction of the Ymir, the desire to create a degree of sympathy for the creature, the animation (well, of course), the lasting appeal of Harryhausen's films and a good deal more.

Remembering 20 Million Miles to Earth (27:01)

Ray Harryhausen looks back at the making of 20 Million Miles to Earth, with contributions from a number of prominent admirers, including director Terry Gilliam and special effects artists Stan Winston and the Chiodo Brothers. A number of interesting titbits are revealed, including the fact that Harryhausen set the film in Italy largely because he fancied a paid trip there. Some of the most perceptive observations come from filmmaker and historian John Canemaker, who shares my sympathy for the creature and its plight.

Interview with Actor Joan Taylor (17:29)

Actor Joan Taylor, who plays Marisa in the film, looks back at her early stage and screen career and recalls meeting Charles Schneer and landing a role in Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, as well as learning a few things about the actors' rights from her co-star Hugh Marlowe, whom she describes as a big union guy. I like him already.

Film Music's Unsung Hero (22:33)

Soundtrack producer David Schecter outlines the work of composer Mischa Bakaleinikoff, who created a number of themes and cues for B-movies whose scores were otherwise comprised largely of recycled material from earlier studio films. Schecter goes into enough detail on this to have those with a fascination for specifics of film score composition enthralled, but it may well prove a little exhausting for others.

The Colourisation Process (11:02)

Having made clear my prejudice on the subject of colourisation above, it was perhaps inevitable that I approached this featurette with a degree of cynicism. The boss people and the creative director of Legend Films talk about the process of colourising three of Harryhausen's early monochrome movies (Earth vs. the Flying Saucers was also coloured in), while Harryhausen himself reveals that's he's delighted with what he has seen so far (it seems likely this was made while the process was still under way) and hopes that the results will dispel the prejudice that people seem to have about colouring in old black-and-white films. Nope. The examples provided from other movies – including a Three Stooges comedy and Laurel & Hardy's Babes in Toyland (aka: March of the Wooden Soldiers) – did nothing to sway my jaded opinion.

20 Million Miles More

Some slides of pages from a comic book series inspired by the film, first issued in 2007 by TidalWave Productions. A big screen is advised for viewing in detail.

Super-8 Version (8:39)

Becoming something of a favourite on Indicator discs, this silent and captioned Super-8 version of the film compresses events down to an insanely brief eight-and-a-half minutes, and half of that is devoted to the climactic creature hunt. At least it's the original monochrome version.

Theatrical Trailer (2:00)

"MODERN WEAPONS HELPLESS TO STOP IT!" and "WORLD-WIDE PANIC!" are a couple of the tabloid headline captions that are splashed across the screen in this engagingly sensationalist sell. If I remember right, that "world-wide panic" is actually confined to Rome – everyone else probably read about it later.

Image Gallery

36 slides of production and promotional stills and a generous selection of international posters.

THE 3 WORLDS OF GULLIVER

Audio Commentary

Steven C. Smith, author of A Heart at Fire's Centre – the Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann is joined by visual effects supervisor and animator Randall William Cooke and screenwriter C. Courtney Joyner for a busy appreciation of the film, one that's packed with observations and information on its production. I learned here that the film was originally intended to be a vehicle for Danny Kaye, and that when this fell through Jack Lemmon was up for the lead role for a while, which despite Lemmon's immense talent I find curiously hard to picture. There's also detail on several of the actors, the locations, the process of creating sodium travelling mattes, and Harryhausen's work on the photographic effects and creature animation. As you might expect, there's quite a bit of discussion about Bernard Herrmann's music and justifiably so – Smith even calls him the co-author of the film. Swift's original novel, particularly some of the ways the film digresses from it, gets several mentions, and listeners are encouraged to give it a read. I'll second that.

The Making of 'The 3 Worlds of Gulliver' (5:22)

Ray Harryhausen talks about the challenge of convincingly showing people of vastly different sizes on screen together, for the most part using travelling mattes but sometimes creatively cutting corners by positioning Gulliver close to the camera and the Lilliputians some distance away, a technique known as forced perspective that was later employed by John Carpenter to place an actor inside the dome of a model spaceship in his micro-budget debut feature, Dark Star.

Interview with Peter Lord (10:14)

Aardman Animations co-founder Peter Lord talks about the impact that Jason and the Argonauts had on him and his contemporaries on its release, recalls the lack of available information on Harryhausen's technique when he was starting out, and the praises the sophistication of Harryhausen's model-making. He also credits Harryhausen with inventing the visual language for how monsters and mythological creatures should move.

Interview with David Sproxton (9:29)

The other co-founder of Aardman animations joins his colleagues in celebrating the influence of Harryhausen's work and looks back at his and Lord's first experiments in animation using his father's 16mm Bolex camera (a personal favourite from film school days). In common with his colleagues, he is amazed by Harryhausen's ability to create complex animations with no assistance from video or computer playback, and describes the worlds Harryhausen created as having a 'magical realism'.

Interview with Dave Alex Riddett (8:38)

Aardman cinematographer Alex Riddett recalls owning the 8mm version of Earth vs. the Flying Saucers and almost wrecking to by watching it frame-by-frame in an attempt to discover how Harryhausen had worked his magic. He talks about his early experiments with animation and reiterates the point made by others about the lack of available information on the techniques involved in model animation back when he was starting out. Rather charmingly, when faced with a challenge even today, he and his colleagues always ask themselves, "What would Ray do?"

Isolated Score

I'm often ambivalent about isolated music and effects tracks, but here I welcomed the opportunity to listen to Bernard Herrmann's majestic score without distraction, and there's enough music here for you not to have to sit in silence for too long before the next piece appears. And it sounds great.

Theatrical Trailer (3:21)

A solidly boisterous trailer for the film that makes hearty use of Bernard Herrmann's score and repeatedly refers to Brobdingnag as 'The Land of the Giants', which was the title of a fondly remembered Irwin Allen TV series from the 1960s that just has to have been influenced by the second part of Jonathan Swift's novel or this very film.

Image Gallery

44 slides of production and promotional photos, plus some of those hand-coloured front-of-house stills and a small sprinkling of posters.

Booklet

I've already said my piece a number of times about how some of the booklets that come with releases such as this almost deserve reclassification as books, and this is no exception, running as it does for 80 information-packed pages. Each of the three films gets even treatment here, kicking off with full credits for the film in question, which is followed by a detailed essay and an 'oral history', a collection of very worthwhile extracts from interviews with relevant filmmakers and actors compiled by Jeff Billington. The essay on It Came from Beneath the Sea by genre enthusiast Kim Newman is a typically engrossing read, and it seems clear that Mr. Newman is intrigued by some of the same aspects of the film as I was (and which I might not have covered had I read this first). 20 Million Miles to Earth is perceptively examined by Dan Whitehead, who shares my gripes about human overreaction and a creature who did nothing to deserve the fate that it suffered. For his essay on The 3 Worlds of Gulliver, Charlie Brigden focuses primarily on the man he regards as the real giant of the film, composer Bernard Herrmann, whose score he deconstructs in fascinating detail. Finally, there are a couple of pages of quotes – again edited by Jeff Billington – about the colourisation process. I've nothing more to say on that particular matter.

Three hugely entertaining films that further showcase the extraordinary artistry and technical skill of Ray Harryhausen, as well as the producing savvy of his long-time filmmaking partner, Charles H. Schneer, all handsomely restored in a box set with so many high quality special features to watch and to listen to that I began to believe I'd never get this review completed. Harryhausen fans should already own this, but if you don't then I'd snap this superb box set up as soon as you can, as this is a limited run and you'll be kicking yourself later. An essential purchase. Roll on the next set!

|