|

When I was a wee lad, I had no understanding of how hellish it was to fight in a war or how hard it could be to be a professional soldier. At that age it was all Action Man dolls, plastic toy guns and “bang-bang, you’re dead” in raucous playground mock battles in which none of us got seriously hurt. Well, usually. Most of what I thought I knew about any branch of the military I’d drawn from old Hollywood movies in which men became heroes at a time of need and got to ride in cool-looking tanks and fighter planes. But even then, the one thing I knew I never wanted to do was go underwater as part of a submarine crew, to be trapped in a narrow metal tube that these movies had convinced me were either lethal underwater predators or motorised aquatic coffins. For reasons I have never been able to explain, I found the sight of an approaching torpedo far scarier than bullets or mortar shells, but even they paled when compared to the nightmarish notion of sub-wrecking depth charges. Back then, it always seemed that if the good guys were in a submarine, then the likelihood was that it would either end up critically damaged on the sea bed with a limited supply of air, or be so wrecked that the crew would have to abandon ship and become the target for enemy snipers or ravenous sharks. And as someone with a mortal fear of suffocation, the choice between drowning when the downed submarine filled with water or struggling to breathe as the air supply ran out was no choice at all.

Gray Lady Down is a 1978 submarine action-drama whose title makes it clear that such a vessel is going to sink, and when the film opens to reveal that Charlton Heston is on his final voyage as the captain of a nuclear sub, the USS Neptune, you know right away that this is going to be the one. Heston plays Captain Paul Blanchard, and at the end of this voyage he’s due to hand command of the vessel over to Captain David Samuelson. Samuelson is played by Ronny Cox, who a few years later would play the no-nonsense and arrogantly self-confident Captain Edward Jellico in the superb Star Trek: The Next Generation two-parter, Chain of Command. Perhaps because of that, I was expecting Samuelson to be a man of similar personality and swagger, and on that score I was in for a bit of a surprise.

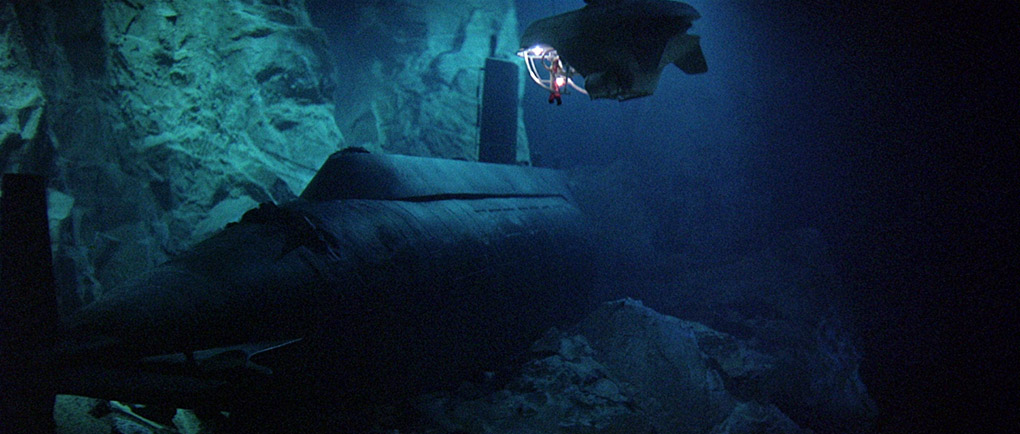

Just a few minutes in, the first of a small collection of clichés in an otherwise solid adventure arrives in the shape of a Norwegian ship whose radar breaks down and whose captain and crew can’t see where they’re going because of thick fog. Maybe it says something about moviemaker perceptions of national insecurity that when disaster strikes an American vessel of any kind in a film, it’s often the fault of some careless foreigners and their inferior technology. Yes, this was made back in 1978, but does anyone recall the nationality of the space station that fell apart and sent Sandra Bullock spinning through space in the far more recent Gravity? Was it American? Of course it wasn’t. Thus, the Norwegian tanker ploughs forward through the fog and can’t see the surfaced sub, and even though the Neptune crew have picked the ship up on their radar, nobody thinks to get the hell out of the way of a craft whose maximum speed is something like 20 knots (about 23mph) at full throttle until it’s almost on top of them. It hits them, they sink, and by chance the Neptune lands on a ledge precariously close to a lethally deep canyon. The rear end of the craft is smashed and the engine room has flooded, killing a substantial portion of the crew. The sub is thus now incapacitated, 1,450 feet below the surface and below its theoretical crush depth, with no working radio communication and only enough air and battery power for one-and-a-half days. Don’t worry, Blanchard assures his men, the crew of the Norwegian ship will report the accident and the Navy will send out a search party pronto. To my very real surprise that’s exactly what happens, and in no time at all a DSVR – a Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle designed specifically to dock with a downed submarine’s escape hatch and evacuate the crew – is being prepped for a rescue mission. The only thing is, with no radio contact, the team tasked with coordinating the rescue do not know precisely where the Neptune is, what condition it’s in, or even if anyone on board is still alive. The Navy brass thus contacts young hotshot officer, Captain Gates (David Carradine), who together with his loyal sidekick Mickey (Ned Beatty) has developed a small experimental submersible, the Snark, that has the capability to safely descend to the canyon edge and locate the downed submarine.

Although technically a submarine drama with action-thriller trimmings, Gray Lady Down does borrow heavily from the 70s disaster film cycle into which it is often lumped, and while a couple of the tropes on display here have their roots in war movies – the young sailor (Michael O'Keefe) who can’t take the pressure and goes colourfully (if temporarily) mad – many others have their roots in the disaster movie subgenre. There’s the initial catastrophe that kicks off the story; an economic introduction of characters, some of whom will be sacrificed later; heroic acts of self-sacrifice and redemption; a circumstance-imposed time limit on any potential rescue attempt; an expert who butts heads with the operation leader; a situation that steadily worsens due to the forces of nature… Ah, yes, the worsening situation. As if a limited supply of air and battery power were not enough, we also have a pressure door that is keeping the sea water at bay but is starting to get damp, then slowly trickling water, then…well, you can guess the rest. On top of that, there are intermittent underwater landslides that hit the Neptune with rocks and sand, covering the escape hatch and threatening to tip the sub over and into the canyon. Bloody hell, could these guys get a break? Also soon to become a familiar trope is the two-man team of Gates and Mickey, who are so cockily confident in their craft and their abilities that they just go about the job of setting up their gear as soon as they board the recue ship, all but ignoring the man in charge of the rescue operation, Captain Bennett (Stacy Keach).

What quickly separates Gray Lady Down from its more effects-driven brethren is the full cooperation given to the production by the US Navy, which allowed the use of real ships, real aircraft and even a genuine rescue vessel, lending the whole enterprise an impressive air of scale and authenticity. In common with just about every theatrical disaster movie of note, it’s essentially an ensemble piece with recognisable faces in the more prominent roles, although some the actors here were virtual unknowns on the cusp of wider recognition. By this point in his career, that character that Charlton Heston played best was Charlton Heston, which he does here with his usual authority and personable charm, and I certainly had no trouble believing him as a respected leader of men. Stacy Keach, meanwhile, isn’t given that much room to breathe as rescue operation leader, Captain Bennett, being only required to act confidently and show concern when appropriate, which he does with the expected aplomb. And then there’s Captain Samuelson. Now, Ronny Cox is an actor that I greatly admire, and for the first ten minutes he is his usual effortlessly engaging self. Once the sub sinks, however, he’s stuck with what may be the film’s most thankless role, as a submarine captain whose reaction to this disaster is not to act like the officer material we presume he must be, but to get all bitter and twisted at Blanchard for destroying his ship. On a Vessel in which everyone pulls together convincingly in the face of this crisis, Samuelson is the only (major) character who feels like a screenwriter creation rather than a member of a well-trained and disciplined crew. In some respects it’s a similar story for the cocksure team of Gates and Mickey, the sort of skilled engineering innovators who would be cut slack to behave like they own the place in just about any organisation except the military. But Carradine and Beatty make for a likable team and are an essential component of the rescue mission, and when Bennett puts his foot down, Gates does tend to respect his position as project commander, despite the two being of equitable rank.

For me, the best and most engagingly naturalistic performances come from members of the supporting cast. Stephen McHattie is reunited here with director David Greene, the man who helmed the actor’s feature debut, The People Next Door (also available on Indicator Blu-ray – this review is sponsored by…) and in the role of Lieutenant Danny Murphy he genuinely feels like a man who has spent a couple of years building a warm rapport with his commander. It’s a similar story with Jack Radar as Chief Officer Harkness, Dorian Harewood as crewman Fowler, and Hilly Hicks as Page, an ordinary seaman with some medical training who has to do his best when the ship’s doctor is lost in the collision. John Carpenter favourite Charles Cyphers has a small role as the Neptune’s calmest sailor, and who’s that handsome devil playing Bennett’s hyper-efficient adjunct, Phillips? Why its Christopher Reeve in his first feature role, just a few short months away before he hit the big time in the title role of Richard Donner’s Superman.

Time has rendered some plot turns a tad predictable (a late-film act of sacrificial bravery is heavily telegraphed), and fun though it is to see submariners watching Jaws and creating their own soundtrack when the projector’s sound dies, I was left wondering if this small but unnecessary drain on the vessel’s slowly dwindling power supply would have been condoned by any sensible commander. It matters little. Gray Lady Down is still a solidly-made and smarter-than-average (at least for its day) disaster-themed action-adventure caper, and while it may at times play like a salute to the work of the submarine rescue team and American military grit, the swiftness and efficiency with which decisions are made has an air of authenticity that is rare for such films. The sinking is well staged – the sight of people trapped in rapidly rising waters stirred up all my old fears – and the subsequent drama is paced well enough to never be dull but also not in the sort of breathless hurry that you just know a modern remake would feel obliged to be. While it never comes close to matching the claustrophobic terror of that towering giant of the submarine movie, Das Boot, it still has its moments, particularly surrounding that slowly weakening pressure door, and a building sense of urgency is emphasised by Jerry Fielding’s excellent score. The model work is surprisingly good, given that it has to be matched with genuine military hardware, and for the most part the actors playing the crews of both the submarine and the rescue ship behave like coordinated and professional teams. That said, my favourite performance moment comes when Bennett asks his partner Liz (Melendy Britt) to tell Blanchard’s wife Vicky (Rosemary Forsyth) that her husband’s submarine has gone down, and the message is delivered and processed primarily through the looks that are exchanged between the two women. Now that’s screen acting.

A largely impeccable 2.35:1 HD remaster that only struggles a little in the early scene of night-time fog, which has a grubby look that may well have been intended, but it still feels as if it’s proved a a bit of a challenge for the transfer. Elsewhere, however, the image really shines, boasting a fine level of sharply rendered detail, a lovely contrast balance that nails the black, and a pleasingly naturalistic colour range that handles the rare brighter colours (the night vision red light that bathes the submarine interior, for example) vividly without any edge bleed. The fine film grain does coarsen just a tad in shots of the DSRV at home base, possibly the result of shooting on higher speed stock in available light in a Navy facility, and the HD image does make it easier to see the wire from which the model of the Snark is dangling. Overall, though, an excellent job.

Oh boy, is this a film that cries out for a DTS-HD surround remix, but since the film was released with a mono soundtrack, that’s what we have here in Linear PCM 1.0. The sound design on the film is first-rate, with clear dialogue and music and a strong use of sound effects to heighten the danger, but more than once I found myself itching to hear it assaulting me from every angle in the manner of the extraordinary surround track on Das Boot. But it is what it was, and is thus authentic to that original release, and on that front it’s fine.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are all aboard.

Audio commentary with Peter Tonguette

Okay, let’s get the petty pedantic stuff out of the way first. As I get older and even crankier, I tend to get irritated by the silliest of things, and one of my most nit-picky bugbears occurs right at the start of this commentary by film critic and journalist Peter Tounguette, when he talks about the film’s opening shot and notes that the camera pans down from the sky to the water. No it doesn’t. A pan involves moving a usually tripod-mounted camera horizontally. When it moves up or down it’s called a tilt. I hear that one so often these days and it always winds me up. And don’t get me started on what I’d like to do to those who describe a forward movement of the camera or a zoom as a “pan in.” You see what a year of lockdown isolation has done to me? That aside, this is a solid commentary that is littered with interesting observations and analysis. Some of it I disagreed with, but all of it I nonetheless appreciated, even when Tonguette does that thing we all do on occasion and read secondary meaning into elements that are either common to other movies or may never originally intended to be read that way. Then again, maybe they were, and it's always fun to speculate. He rightly highlights the work of sound effects editor Peter Berkos and casting director Lynn Stalmaster, both of whom he has interviewed, as well as commenting on the actors, director David Greene, cinematographer Stevan Larner, editor Robert Swink, and score composer Jerry Fielding. Although a big fan of the film, he reads from several of the more negative contemporary reviews without scorning them, and it’s through this commentary that I learned that further sequences involving the Navy wives were cut by David Greene, as well as why they were removed. Where I really bonded with Tonguette is in the links he highlights between this film and Richard Lester’s 1974 Juggernaut, a superb and too often undervalued work that Tonguette describes as “a better film than Gray Lady Down and one of my favourite films of the 70s.” Sir, I salute you. But it’s tilt, not pan.

The Guardian Interview with Charlton Heston (74:39)

Conducted by Quentin Falk at the National Film Theatre in London in 1985, this on-stage interview with Charlton Heston comes with the usual warning about sub-par audio quality, which only really becomes an issue when we get to the audience questions, and many of those are repeated by Falk anyway. Right from the start this proves to be an entertaining listen, even if some of the stories told by Heston have since become part of film lore. Prompted by Falk and referencing three film clips that were shown before they took the stage, Heston kicks off by talking in some detail about his work on Touch of Evil, praising the film’s boom gaffer for his work on that extraordinary opening shot and describing director/star Orson Welles as “the most talented man I’ve ever met.” He moves on to discussing Soylent Green, outlining the plot in some detail and recalling that none of those working on the film knew that Edward G. Robinson was dying whilst making it (he passed away shortly after filming his final scene). There’s also some coverage of Heston’s second film as director, the 1982 Mother Lode, which I have to confess to never having seen. I was also unaware that he had turned down key roles in Paths of Glory and Deliverance, in both cases because of scheduling conflicts, though he does say of the latter, “Burt was bloody good in it.” Audience questions prompt discussion on working with directors William Wyler and Anthony Mann on Ben Hur and El Cid respectively, the journals he has been keeping for years as a work tool, working with Franklyn J. Schaffner on Planet of the Apes and The War Lord, and more. When asked about his role in Sam Peckinpah’s Major Dundee, he recalls that he, the studio and Peckinpah all thought they were making different movies, and that Peckinpah eventually realised his original vision as The Wild Bunch, which Heston describes as “a marvellous film.” No arguments here.

Stacy Keach: Lady’s Man (11:58)

An engaging, pandemic-enforced Skype interview with Stacy Keach that kicks off with him quickly summarising the career path that led to Gray Lady Down, including his prior teaming with David Carradine on Walter Hill’s The Long Riders, and his theatre work with Ronny Cox and Ned Beatty (you know he’s a Shakespeare buff when he refers to Macbeth as ‘The Scottish Play’). He recalls believing that then newcomer Christopher Reeve would be a great actor, that David Greene was very good at handling action scenes, and that the Navy personnel were great and fully cooperative. He also deeply respected and became good friends with Charlton Heston, and recalls being heartbroken when the legendary actor took a hard political turn to the right.

Stephen McHattie: The Changing Tide (7:13)

An audio-only interview with actor Stephen McHattie, who describes the film as anomalous for its time and a throwback in its uncritical presentation of the military, and recalls being part of a supporting cast group that came from a similar theatrical background. He also comments on the differences in David Greene’s direction of this film to his work on The People Next Door, and how his own terror of Hollywood sent him running straight back to the theatre as soon as shooting was complete.

Alan K Rode: Plumbing the Depths (40:53)

Now this is interesting and a bit of a coup for Indicator, an interview with critic, producer and film historian Alan K. Rode, who in his previous career was in the US Navy and stationed on the USS Pigeon (the rescue ship that appears in the film), where he took care of the Navy’s two rescue DSRVs. He’s a fountain of knowledge on all things sub-nautical, providing a detailed history of how these submarine rescue craft came to be commissioned (the story of the USS Tang, which was sunk when its own malfunctioning torpedo circled back around and hit it left me jaw-dropped), as well as the development of nuclear-powered submarines and the craft that have since replaced the DSVRs seen in the film. It’s really interesting stuff and I learned a lot from this. He does also comment on Gray Lady Down, which he admits to enjoying, though does question the plausibility of the crew’s slow reaction to the approaching Norwegian ship (“There is no excuse for a collision at sea”) and describes the character of Samuelson as unrealistic. He also reveals that his favourite line of dialogue in the film is, “I feel like a one-legged man in an ass-kicking contest,” as it’s a phrase that he regularly used on board ship during his Navy years.

Theatrical Trailer (3:20)

A grubby, 4:3-framed trailer with a morose narrator, a couple of sizeable spoilers and an opening that is essentially a compressed version of the collision and sinking sequence, this is nonetheless a very snappily edited sell that would have me adding the film to my watchlist.

TV Spot (0:31)

A compressed version of the above with no serious spoilers.

Radio Spots

Radio Spot #1 (0:31) has a more excited (and hyperbolic) narrator than the one on the theatrical trailer, and with only a brief clip from the soundtrack of the film and a musical backing, he needs to be. The same narrator drives Radio Spot #2 (0:31), and I feel I could write a couple of paragraphs about his dodgy script. Describing the nuclear submarines as “the most perfect undersea craft ever designed by man,” he then asks what happens when one of them is rammed and sinks. Hardly perfect then, is it? We’re then told that the film is “a once-in-a-lifetime experience in suspense” and “the most fantastic rescue mission ever imagined.” To quote Han Solo in the original Star Wars, “I don’t know, I can imagine quite a bit.” He’s back again for Radio Spot #3 (0:31), but here dials it back a bit and goes with “The suspense thriller of the year.” You can play these separately or all together.

Image Gallery

58 screens of promotional imagery. The production stills are a mixture of crisp monochrome photos and colour ones that vary a bit in quality and colour fidelity, but the best images (usually on the deck of the rescue ship) look fine. There’s also a single shot of David Greene directing Charlton Heston, and portraits of Heston and Ronny Cox in full naval uniform, complete with caps. Iffy colour tinting is showcased by some German lobby cards, and I was interested to discover that the film’s German title is U-Boot in Not, a handy reminder that U-Boats were not a specific wartime class of submarine but the German term for all such undersea vessels (it’s short for Unterseeboot, literally “undersea boat”). A couple of posters and some poster artwork round things off.

Also included with the release disc is Limited Edition Exclusive Booklet with a new essay by Omar Ahmed, archival articles on the film, an overview of contemporary critical responses, and film credits, but this was not available for review.

I haven’t seen Gray Lady Down since its original release and enjoyed seeing it again for what felt like the first time after all these years, and while I think I feel more critical now of the aspects that don’t quite work for me, I’m also more appreciate of what the film does well, and there’s a lot of that. As for the Blu-ray, the transfer is first-rate and the special features are well up to the usual high standard that Indicator has set for its releases. It may not be one of my favourite films, but I still have no problem warmly recommending this disc.

|