The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,

Awaits alike th' inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave. |

| Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard by Thomas Gray |

Before I get started I should warn you that there are spoilers ahead, some of them huge. The simple fact is I couldn't talk about some of the things that bowled me over about this extraordinary film without discussing scenes that are best discovered first by watching the film. The bigger reveals don't occur until later in the review, so I've added a second warning just before I start really ruining things for first-timers to give you a second chance to bail out and skip forward to the technical specs.

You don't have to be a card-carrying pacifist to have a dim view of the handling of some of the military campaigns during what came to be known as the First World War. One of the things for which this particular conflict became famous – or perhaps that should be infamous – was the appalling number of deaths and casualties that resulted from soldiers being ordered to walk into lethal enemy fire by military commanders who were comfortably distanced from the front. Then there are those who were executed by their own side for acts of cowardice or desertion, 346 men in British ranks alone, although a further 2,734 death sentences were handed out but not seen through their ultimate conclusion. Many of those so charged are now believed to have been suffering from shellshock, a condition that was poorly understood and even rejected by the military authorities of the day. And Britain wasn't alone on this score or even the worst offender. During the course of the very same war, it is estimated that at least 600 and possibly as a many as 900-plus French soldiers were executed by firing squad for matters related to 'disobedience'. The majority of these men are believed to have been killed not to be punished but to set an example to their fellow soldiers.

Unlike a number of other Stanley Kubrick films – 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon among them – I can't remember when I first saw Paths of Glory, but I do vividly recall the impact that it had. It was a film that my closest friend and I had a unified enthusiasm for during our college years and from which we would freely quote, emulating the manner in which Kirk Douglas or George Macready had delivered specific lines in the film. I do, however, clearly recall a viewing from several years ago that said some telling things about the film's emotional clout and the sense of outrage it is still able to provoke. My family came to my house for Christmas dinner, and each year they invited a friend to join them in order that he wouldn't spend the day on his own (sounds like bliss to me, but that's beside the point). He was actually a regular attendee at our film society, and although we regularly chatted after the screenings, we rarely seemed to agree on what made a great film. As my parents departed, Paths of Glory began screening on TV, and our guest asked if he could stay on and watch it with me, despite the fact that he actually didn't have much time for Stanley Kubrick films (see what I mean?) Although not wanting to have one of my favourite films blighted by a string of derogatory comments from someone whose views I had little real time for, I agreed to let him stay. To my surprise and relief, he sat quietly and attentively for the first half of the film, but when the politics of power really kicked in, that quickly changed. "Bastard!" he spat as another cruel twist saw good men fall victim to the egotism and ambition of those in positions of authority. The more the innocent suffered, the angrier he became. He was no longer watching a film set in the First World War, he was witnessing and responding to acts of terrible injustice that tragically have their ignoble roots in actual events.

We're in France at the height of WW1, and the order comes down from the High Command for a heavily fortified German entrenchment known as the Ant Hill to be taken, despite the repeated failure of previous efforts to do so. General Broulard offers the job to General Mireau, who protests that his division has been severely depleted, his men are exhausted, and that taking the Ant Hill is an impossible task. But when Broulard dangles the prospect of a significant career advancement and drops hints that it may rely on the success of this operation, Mireau has a change of heart and becomes convinced that the task is within the grasp of his troops. When the attack is launched, however, led by the battle-hardened Colonel Dax, the sheer intensity of the enemy firepower quickly brings it to a halt and even prevents one company from leaving the trenches. Outraged by what he regards as a cowardly betrayal, Mireau sets a general court martial in motion, but following intervention from Dax and Broulard, agrees to have one randomly picked soldier from each of the three companies in the first wave symbolically tried under penalty of death for cowardice.

Such a summary covers the essentials of the film's first half, but gives no flavour of what makes it so utterly riveting as drama and so astonishing as cinema. That this is not going to play to genre expectations becomes clear early on as cinematographer George Krause's camera glides smoothly with Mireau as he walks through the trenches in a manner that would later become a Kubrick signature. Later this same technique is used to far more unsettling effect, moving through the trenches with Dax as he readies himself to lead the charge with an expression of grim determination on his face, intermittently switching to his viewpoint as walks. As shells explode around him and soldiers duck down nervously, all too aware that their next minute may be their last, my stomach knots up every time as I am forced to contemplate just how I would react or even cope in this situation. I can't think of many scenes that communicate the terror and danger of being under fire as vividly as this one.

It also sits in powerful contrast to our earlier visit to this same trench, where the camera walks instead with General Mireau and his kiss-ass of an adjunct, Major Saint-Auban, as they inspect the troops, Mireau stopping intermittently to ask each soldier the same supposedly morale-boosting question: "Hello there soldier, ready to kill more Germans?" When a third man fails to respond to the General's enquiry and breaks down at the prospect of never seeing his wife again, Mireau is incensed, slapping the man's face, dismissing the very idea of the shell-shock from which he is clearly suffering and demanding that "this baby" be immediately transferred out of his regiment. "I won't have other brave men contaminated by him!" he pompously barks. Unknowingly, this order may well have saved the man's life.

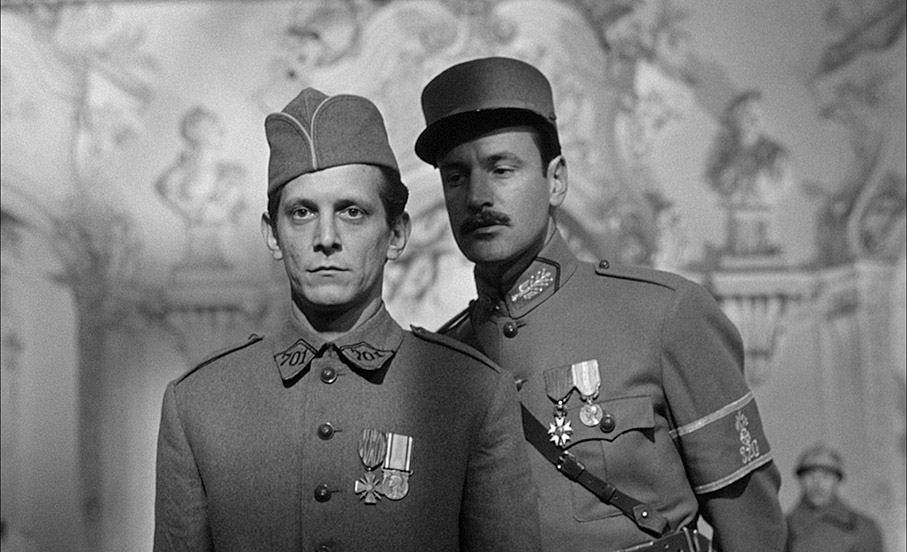

But even before we make our first visit to the trenches, the film intrigues with the political machinations and ambition that, in the space of a few fateful minutes, transform Mireau from a commander who shows genuine concern for the welfare of his men into one who sees and hungrily grasps a proffered bribe of personal advancement and military glory. Despite being entirely dialogue driven, the scene grips the attention from its opening seconds, in part due to an excellent screenplay by Jim Thompson, Calder Williams and Kubrick himself that imbues almost every line of dialogue with narrative purpose and secondary meaning, something the actors respond to with arresting aplomb. Kubrick hits the ground running here in the casting of veteran screen actors Adolph Menjou as Broulard and George Macready as Mireau – both are at the absolute top of their game here, Menjou in his amiable air of confident superiority, Macready in his arrogance and sense of self-importance. Indeed, it's Macready's delivery that makes so many of his lines quotable by imitation, peaking in his furious proclamation following his order that a general court martial be convened, "If those little sweethearts won't face German bullets, they'll face French ones!" The angry rise in pitch of Macready's delivery is visually accentuated by the rapid dolly into facial close-up, while the drama of his delivery feels absolutely right for a man not used to having his words or actions questioned and who takes the failure of the assault as a personal affront.

Playing his own game of lethal personal politics with the situation is Lieutenant Roget (Wayne Morris), who finds what courage he is able to muster at the bottom of a bottle and whose panicky behaviour on a night-time sortie results in the death of one of his own men. Later, when ordered to select a man from his company to stand trial for cowardice, he picks Corporal Paris (Ralph Meeker), the only witness to his actions and a man who – a touch ironically – kept his nerve when Roget was running out on his. As we move down the ranks to the three soldiers selected to be tried for a crime that none has committed, the layers of injustice just keep piling up. It becomes abundantly clear that all three men are undeserving of even a verbal reprimand for actions during an assault that was doomed to fail from the start: Private Ferol (Timothy Carey) is not the sharpest stick in the bundle and was selected by his Captain because he was deemed to be "a social undesirable"; Private Arnaud (Joe Turkel – barman Lloyd in The Shining and Eldon Tyrell in Blade Runner) was randomly chosen through the drawing of lots and has a number of commendations for bravery; and Corporal Paris was knocked unconscious before he was able to leave the trench. It was only on something like my third viewing that I realised that two of the men that Mireau earlier questions on their readiness to kill Germans are Ferol and Paris, while Arnaud is standing almost next to the shell-shocked soldier who so disgusts the General.

If you ignored my spoiler warning above and made it to this point, this is your last chance to bail out and go watch the film instead. There are spoilers aplenty ahead, and I'm even going to talk about the film's final scene. If you've seen it you'll understand why.

From the moment the assault begins to show clear signs of failing, it's Mireau's pomposity and refusal to find fault with his own decision that propels the story forward and seals the fate of the soldiers selected to stand trial. Pushed by the more politically savvy Broulard to compromise his initial demand that a hundred men be shot as examples, he takes very personal offence when Dax – a celebrated criminal lawyer in civilian life – asks that he be appointed council for the accused men, a request that is cheerfully granted by Broulard. In a civilised society Mireau's own words and behaviour would be his own undoing, but in the rarefied world of the military high command, he is not only given all the latitude he needs, but his position is supported by court officials who seem almost put out that they should have to waste their valuable time on such an obviously open-and-shut case. Seemingly to wind up the audience further, the case is prosecuted by Mireau's self-satisfied adjunct Saint-Auban, who relishes the opportunity to perform for his General and even flashes knowing looks and smug smiles at the court officials as he makes his case. Rarely have I wanted to punch a film character more than I did Saint-Auban during this scene – full marks here to Richard Anderson (later to find fames as Steve Austin's boss in The Six Million Dollar Man) for creating a character so infuriating without ever overplaying his hand. His later discomfort at the result of his courtroom performance provides only a small flavour of the emotional slap of which he is insuch dire need.

Despite being selected as symbolic representatives of the entire attack force, each of the accused is required to explain specifically why they as individuals failed to reach the enemy line, but from the start they appear to have been judged guilty by default, and every argument that Dax even attempts to put forward is countermanded by a series of infuriatingly restrictive dismissals. In complete contrast to Mireau, Dax is a model of integrity and military professionalism, and once again is cast to absolute perfection. I would rate this as one of Kirk Douglas's very finest performances, and even as I write that I'm unsure of what roles from his remarkable career that I would pick to compete against it. Rarely has his gritted-teeth anger been put to more effective use, and like Macready his delivery makes every line of dialogue register on more than one level, as diplomacy shapes his words but his true feelings always come through in his inflection and facial expression. My absolute favourite example of this comes when he offers Roget the job of leading the firing squad, fully aware of his true motivation for selecting Paris to be tried for cowardice. After listening to the Lieutenant's nervously bumbled request that he be excused this duty, Dax growls with a barely supressed blend of anger and contempt, "Request denied," cutting short a further protest with, "You've got the job. It's all yours." It may not read like much, but you should hear how Douglas delivers it. For some years, my aforementioned friend and I would gleefully imitate this line and its delivery every time one of us foolishly made a request of the other.

In spite of the precise manner in which it is filmed, the decision to shoot on location in actual chateaus and specially dug trenches in German farmland lends the proceedings a disconcerting air of realism (it no doubt helps that our documentary experience of even the wars that immediately followed are all in monochrome – shooting in colour would have broken the spell here). Having set this tone in the aforementioned trench walks, Kubrick ups the ante further once the assault begins, tracking alongside Dax as he leads his men into no man's land, as shells rain down around him and soldiers fall victim to enemy fire on every side. It's as vivid a picture of war as hell on earth as you'll find in a film before Elem Klimov's Come and See left us gasping for air.

Nowhere does Kubrick's intermittent switch to a subjective viewpoint register more grimly than in the climactic scene, where the three condemned men are walked ceremoniously towards their place of execution as officers, soldiers and press watching on from both sides and military drums marking their final heartbeats, a sequence that hits me in the pit of my stomach every time I watch it. Those too-often levelled charges that Kubrick was a technically brilliant but emotional detached director have absolutely no place here – his aim was clearly not to observe the final minutes of the three condemned men but to force us to share them, to put us in their place and experience just a whiff of their fatalistic fear, as a subjective dolly shot pulls the posts to which they are be tied inexorably towards them like a trio of monolithic angels of death. Adding a further layer to the outrage of this lethal farce is the fact that the unconscious Arnaud, who has sustained a serious head injury during a brawl with Paris, is propped up against his pole in the stretcher in which he was transported, then woken so that he will be at least partially aware that he is about to be shot. Mireau's later gloat that "the men died wonderfully" adds a final level of insult to injury, while the small victory handed to Dax by Broulard rings hollow because the General has completely misinterpreted Dax's intentions. "You really did want to save those men, and you were not angling for Mireau's command," he says as if the notion itself was completely alien to him, adding, "You are an idealist. And I pity you as I would the village idiot."

As drama, the effect is genuinely overpowering, and yet in spite of the impact of what has come before, the film's biggest and most unexpected emotional punch comes in its final scene, as a group of raucous French soldiers on furlough are serenaded by a frightened young German woman (played by Susanne Christian, Kubrick's wife-to-be) at an inn in which the men are loudly unwinding. Initially drowned out by their shouts and whistles, her simple but haunting song gradually silences the men and awakens in them a deep longing for family and home, prompting them to hum along and even reducing a few to tears. Captured as a series of emotively framed and shallow focus facial close-ups, it's a stunningly executed and intensely moving scene, and the perfect rebuke to those who still like to cast Kubrick as an unfeeling machine.

Paths of Glory has frequently been cited as one of great anti-war films, but for the most part it is not war itself that the film is targeting but the sometimes inhuman manner in which this particular conflict was managed. The nature of war may have changed in subsequent years, with conditions such as shell-shock now acknowledged and better understood, and infantry soldiers no longer ordered to walk to their deaths under a hail of machine gun fire in their thousands by commanders comfortably distanced from the front. Yet as we have become all too aware in recent years, soldiers are still sent into battles in which hundreds will lose their lives on false and flimsy pretexts by politicians who will never see a day of military action. And the story told here can also be read as a topical and all too pertinent parable on the workings of modern corporate capitalism, as the greed and ambition of the detached and cosseted one per cent have a devastating impact on those at the bottom of the social strata, destroying the lives of individuals who are little more than a decimal point in manipulated statistics to these new industry generals and their global power games.

The general opinion is that Paths of Glory was the film in which Kubrick's signature style was first clearly crystalized, and despite the very real rewards and thrills of The Killing (1956), you'll get no argument from me on that score. The distinctive use of wide-angle framing and locked-on-character camera moves would become Kubrick staples, but every shot here has been crafted with purpose and every edit timed to perfection. The performances are excellent across the board, and despite having little in the way of physical action, it's one of the director's most briskly paced works, while in terms of its political and emotional impact I'd argue that it has no peer in Kubrick's enviable oeuvre. Many years after I first saw it I am still left reeling by every viewing and stunned by the skill with which it is crafted. It's an extraordinary work even by this remarkable director's seriously high standards, and one that I have absolutely no qualms about labelling a masterpiece.

Having only ever experienced the film on TV or DVD in less than pristine condition and framed 1.33:1, the 1.66:1 HD restoration here genuinely knocked me for six. There is a significant increase in picture detail over any previous standard definition print, something that really pops on mid-shots and close-ups, aided by a monochrome tonal range that is often close to sublime. The black levels in particular are nailed without swallowing shadow detail except when we are not meant to see it – the night sortie in which the bodies of fallen soldiers only become visible when a flare is launched is an excellent example of this. Film grain is visible but is not exaggerated by digital enhancement and feels completely organic to the image. There are a few remaining dust spots and very small instances of damage still evident, and there is occasionally some minor movement of the film in frame, but on the whole this is an excellent restoration and far and away the best I've ever seen the film look.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack displays some (unsurprising) range restriction, but is otherwise in impressive shape, with no background hiss or damage, appropriately thunderous explosions and clear reproduction of the dialogue whatever the location and background activity. The exchanges in the courtroom scene in particular are as distinct as I've ever heard them.

Optional subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are also available.

Commentary by Adrian Martin

Australian film scholar and critic Adrian Martin is rapidly becoming one of my favourites when it comes to so-called expert commentaries, and his contribution here is one of his best yet. Such commentaries sometimes can feel dry, but Martin always feels as if he's speaking from the heart, and while he's doubtless working from notes, he's clearly riffing off them rather than reading from a prepared script. And it really makes a difference. There's a lot covered here, from the factual to the analytical to quotes from other works and even negative contemporary reviews by Truffaut and Godard, all of it worthwhile and much of it fascinating. The only point I'd question him on is his assertion that we never really know why the Ant Hill must be taken, whereas it's actually outlined concisely by Broulard and Mireau in the opening scene.

Peter Kramer (14:33)

Film scholar Peter Kramer provides a useful outline of the film's journey from conception to production, including the hiring and work of writer Jim Thompson, and explores varying stories of the process of bringing the film to the screen, illustrated by some welcome (and high quality) behind-the-scenes stills.

Richard Ayoade (23:34)

Director and actor Richard Ayoade dismisses the idea that Kubrick was a cold filmmaker – indeed, he describes him as one of the most emotional directors there has ever been – and celebrates the handling of the courtroom scene and Douglas's performance, as well as discussing the characters, what he regards as the film's absurdist humour, how characters hold on to their delusions tightly in Kubrick films, and plenty more.

Richard Combs (9:58)

Respected film writer Richard Combs offers some intriguing and persuasive observations on the film's almost military rank-based use of light and the dance-like quality to the character interaction, and also discusses the work of writer Calder Willingham and the influence of the cinema of Max Ophuls on Kubrick's style.

Trailer (3:01)

A leisurely structured trailer (the proclamation that this is Douglas's finest role is followed by his most impassioned speech in its entirety) peppered with spoilers and topped with press quotes and that assures us that "Since the publication of this book 25 years ago, no-one dared to make this movie – it was too shocking, too frank."

Booklet

These are always good, and this one is no exception. The first half is given over to an excellent new essay by Glenn Kenny that traces Kubrick's journey to Paths of Glory, explores its production and analyses what makes it such a great film. This is followed by a 1959 essay by Colin Young from Film Quarterly that looks at Kubrick in the context on non-Hollywood directors, with particular emphasis on Paths of Glory. Credits for the film, production stills and notes on viewing are also included. Just one thing, if you're new to the film and looking to avoid a single spoiler, then I'd steer clear of the booklet's cover illustration.

One of the greatest films from one of twentieth century cinema's most talented and visionary practitioners is here given the presentation it deserves and backed by a solid set of extra features – I was particularly impressed that there is so little overlap between the individual interviews and the commentary track, fully justifying the inclusion of each. A marvellous release. Highly recommended.

|