| |

Although its script is more intellectual than explosive and its cast more garrulous than mobile, "Fear and Desire" evolves as a thoughtful, often expressive and engrossing view of men who have "traveled far from their private boundaries." And it augurs well for the comparative tyros who made it. |

| |

New York Times Review 1st April 1953 |

I love the idea that the great Stanley Kubrick was once a 'tyro'... It beggars belief. Unless you are Orson Welles (and most of us are not), your first film made in the flush of relative youth is always going to be an ankle paddle before later-career immersion – especially if your budget is lower than a Vin Diesel voiceover. You are hugely affected, some may say buffeted, by every movie you've seen up to that dizzying point of making your first creative decision on a film set. You cannot help be steered into certain paths. In the 50s, Kubrick moved with an art-conscious crowd based in New York and peer pressure may have had everything to do with his decision to make a feature at the ripe old age of twenty-four. Even Orson Welles had to have been affected by what had come before. In his later years, he suggested that filmmakers should not see any movies to allow their own personal style to come through with no imagery and technique from others' work perverting their true self-expression. It's an ideal, granted but farcically impractical. Welles was treated to a personal film school that drilled into him all he needed to know. The legend goes that he watched Stagecoach every day for a month and then declared himself ready to direct Citizen Kane. What a graduation movie... The very antithesis of this impossible 'tabula rasa' has to be Quentin Tarantino who seems to have built a career making movies about other movies he's loved. Django Unchained is entertaining enough but you can't take it the least bit seriously, can you? And why would you want to?

If Fear And Desire did anything to make Stanley Kubrick into the master director he was to become, it was to take away the veils of mystery and arcane impenetrability of the film industry in the 1950s and also out of the act of filmmaking itself. In our digital age in which most westerners have in their pockets the means to make a high definition movie, the mystery of filmmaking seems impossibly dated but in the 50s, the business and equipment had an exclusivity about them that deterred all but the most passionate and driven. After Fear And Desire, Kubrick knew he'd leapt high over a significant psychological hurdle and it blasted him forward. And so began the career of a singular talent who was to go on and forge a modest number of extraordinary films with absolute creative control over the lion's share of them. It seems trite and obvious now, fourteen years after his death, to say that there are film directors and then there is Stanley Kubrick. Whether his specific and unique fame was the subtle blowing of his own trumpet or if it developed simply by dint of the quality of his work, Kubrick soon earned his stellar reputation as one of very, very few genuine auteurs in movie history. I hesitate to use the word 'auteur' but I didn't want to say 'genius' either. Both terms are loaded and both are used too indiscriminately in film writing for me to be comfortable. But Kubrick really is the one filmmaker to whom I may grant absolute authorial credit as he was famous for poring over every detail.

There is no one out there, past or present, quite like Stanley Kubrick. His reputation was one of genius-recluse but those who knew him and worked with him came away with their own impressions, wildly at variance with the cliché. I know two people who have been involved with Kubrick professionally and both had nothing but good things to say about him. Also there is a persistent idea floating around that because he was exact and methodical, his work was somehow cold and unemotional. From personal experience of almost all his work, I have to say that this is a convenient but deeply flawed assessment of one of the most brilliant artists of the 20th century. I will refrain from going through my Kubrickian highlights but I am also looking at this movie, his first dramatic work, through 21st century eyes and have no early 50s' context to peer through. So with the virtual dandruff of cynicism and apathy brushed off my metaphorical shoulders, let's see what 24 year-old Stanley came up with... (and in later years, all but disowned...)

Well. OK. Uh...

Do those three words say too much or too little? How about an "Hmmm, I see." To be brutally frank, Fear And Desire is a young man's interpretation of enormously complex and profound themes explored with a little more technical artistry and philosophical clout in future productions but alas not in this one. It's also a shadowy mimic of well-trodden film paths; German expressionism, anyone? Eisenstein editorial motifs? All present. It's a sort of Conrad's Heart of Darkness but with less heart and more cod-philosophy. You can see seeds here of a future Kubrick if you squint tightly enough. Retrospective hindsight has pushed Fear And Desire into the Kubrick oeuvre and I have read many reviews that have pointed out themes and stylistic minutiae that Kubrick goes on to perfect in later films. This strikes me as a trifle disingenuous. For a student film, it is outstanding in many aspects and I would champion the young filmmaker in the same way The New York Times did in the past. But as a 'Kubrick film' with all that this implies, it comes up woefully short. At this stage, the very start of his career, he was not in command of some very basic film craft (unless he was so far ahead of his time, he was mocking and subverting convention even then) and so every minute there's something that jars. The crisp black and white photography is a consistent plus – the self-taught cameraman-Kubrick was a gifted cinematographer – but many times, the film trips up over basic film grammar. Close ups, striking and startling though they are in and of themselves, rarely match in continuity and the movie's rhythm is often chopped at the knees when we cut to one. Eye lines are often askew and the all-important invisible line of action, the very basic root of all narrative filmmaking, is crossed on a regular basis. At 28' 25", Mac (Frank Silvera) sees a small plane through his binoculars and then as the point of view moves panning right you cut to Mac panning the binoculars to the left. This seems like such a fundamental error. Another technical hic-cough occurs throughout the film as Kubrick had rashly decided to loop the film (re-record the actors' lines) in post and paid little heed to the sound recording on the production. Not only is this rather obvious, it ballooned the already paltry budget forcing Kubrick to shoot another corporate film (The Seafarers) to fund the post-production. It gives me no pleasure to claim that even the justly revered Stanley Kubrick was once (dare I say it?) technically naïve; in other words, human. Big exhale. I do not want my heroes to have plasticine galoshes but I have treasured finding out that Stanley Kubrick was wonderfully human after all.

The movie's story kicks off with a voiceover telling us that we are in the context of war but a metaphorical one, any war at any time but one with a 1950's sensibility and context. So the template is in place. It's understood that we are going to read metaphors in almost every scene. The four men, stranded six miles behind enemy lines, all seem to be cod philosophers of a kind and do not represent real people in almost any manner. They are cyphers and presumably designed and created as such. Wanting to get back to their side of the front line, they agree to build a raft. All four have their own demons (briefly illustrated in one travelling scene by a flurry of overlapping voiceovers as each man unveils his own private fears as thoughts out loud all mixed together. It was Kubrick's version of Peep Show for a minute there). There is the hot-headed youngster who has no previous life experience to draw on. This character, Sidney, is played by soon to be director Paul Mazursky. We have the leader, Lieutenant Corby played by Kenneth Harp. He also plays his enemy doppelganger, the General whose dyed grey-white hair is the only thing that distinguishes him from the 'good guy'. I felt being nudged in the ribs here... "Geddit? The bad guy is played by the actor who plays the good guy, geddit?" It hammered this idea home with having his second in command played by the second in command good guy. OK, I got it.

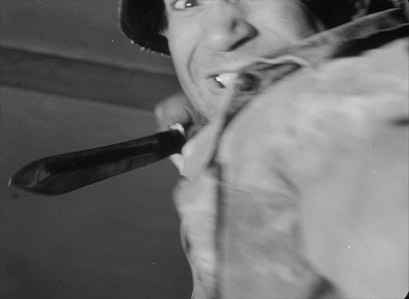

The stilted dialogue and deliberately 'profound' utterances can only exist in an allegorical context and despite this, there are moments of action that are effectively performed and executed. While we never get to really care for anyone, save for Virginia Leith's 'the girl', the film is still intelligent enough to recognise the emotional limitations of its own format. You're never going to be moved by this story. It may prompt thought and discussion but it's not a tale to elicit tears or any other extreme of emotion. The brief, literal stabs of violence are artfully shot and cut and Kubrick cannot resist adding welters of symbolism in some of these scenes. The young 'enemy' soldiers are brutally stabbed and beaten to death as their hands squirm and slosh about in the stew they were eating. It spills to the ground in a very obvious symbolic connection to liberated viscera. Lovely. By far the most commented upon scene is the disintegration of Sidney. The team capture a local girl and fearful that she may inform their enemies of their presence, she is tied to a tree. Sidney is left to guard her and after being forced to kill for the first time (one assumes), he seems to fall apart in front of her as if she was a catalyst for his accelerated madness. It doesn't help the scene one bit to have poor Paul Mazursky deliver lines like "If you have to hate me, please try to like me also..." Sheesh. Incidentally, Fear And Desire's screenwriter is Howard Sackler, a high school friend of Kubrick's, author of the prize-winning play, The Great White Hope. He's also rumoured to have had a role in the crafting of the Indianapolis speech in Jaws. But Sidney's disintegration is played with some gusto and you do fear for the girl. There is a fascinating revelation about this scene in the book The Stanley Kubrick Archive, less of a coffee table tome, more of a coffee table. At one screening this descent into madness elicited laughs and apparently this reduced Kubrick to tears. Absolutely fascinating.

As a first feature, I'm delighted to report that the original budget was $10,000 (the budget on my first feature was £10,000) and both of our films featured girls tied to trees and harassed. Who'd have thought it? And there my own crossover with the great Stanley Kubrick can rest. His budget ballooned because of the disastrous decision not to shoot professionally recorded sync sound as mentioned earlier. In hindsight, no filmmaker is going to be satisfied with a first effort although that honour is now officially Killer's Kiss in the Kubrick oeuvre. Fear and Desire has been relegated to 'early work'. Kubrick himself is scathing ("it's no different from a 16mm student film except it's shot on 35mm...") but you can't deny the attraction of reviewing a mostly unseen Kubrick movie; it's like a glimpse of the acorn falling knowing full well how momentous the oak turned out to be. I will also admit that his seminal 2001 is one of the reasons I turned to film-making in the first place. So Kubrick and his glorious work have enthralled me for a long time, despite the intervening years between each new film. He died at the wrong time (who dies at the right time?) in 1999. Cinema technology was about to explode and the inherently and chronologically film-based Kubrick was often astounded at what was possible in the digital realm. Now a Kubrick movie with today's technology... That would be something to see. He could have finally realised his long cherished Napoleon movie – the 'Massive' software just perfect for huge scale battle reconstructions. Fear And Desire has its moments and it's a fascinating first picture but it's very far from a 'Stanley Kubrick Film'.

The clean up by the Library of Congress is extremely good given the age of the neg. How does 35mm black and white scrub up so well? There is some dirt visible but it's hardly detracting. And those close ups really zing with detail. It's presented full frame 1.37:1 with some shots showing a rounded black matte visible in the lower right corner but again, not distracting. Grain is evident, particularly in some of the darker scenes, but again it doesn't detract. The blacks are pitch black dense and the contrast overall only contracts again in the darker scenes. In fact, the image quality is extremely good given its age.

The mono PCM soundtrack is clear (well, the dialogue would be as it was all recorded in post and sometimes this is obvious) and the general mix is quite lively. I understand the audio was not only cleaned up but also remixed which is a plus for quality and a minus if you are a purist. There are subtitles in English as an option.

And it's here we score over the US release last October. For Kubrick fans, this is the disc to own to finally tick all those boxes. On the US Blu-ray, only the corporate film The Seafarers is included but here we also have the two shorts that Kubrick made cutting his teeth and learning his craft.

The Seafarers (28' 55")

You can tell a film was made in the 50s more easily than most periods. They have an assumed authority, earnest voiceovers and an almost innocent optimism. The Seafarers promotes the Seafarers International Union and has that 'we're all in it together' attitude. Famous US broadcaster, Dan Hollenbeck introduces the film reading quotes from Conrad (he gets everywhere, doesn't he?) and once the credits are over (please someone invent drop shadow soon), the first shot of ships in dock starts with a lurch upward – a mistake! But it was edited in deliberately. Maybe they were running out of material but really, the first shot... It's also Kubrick's first colour film and has that happy, garish nature that corporate films often exhibit. It's very news-reely.

The film physically jumps around, quivering in the gate and quite a few edits flash at you – the result of film cement aging faster than the stock itself. There are also variations in exposure throughout and missing frames. Again, it seems as if all the sound has been done in post aside from Hollenbeck's introduction and a few sync pieces. The music is a full on 50s chirpy orchestration that really grates on you once it's left alone to support the visuals particularly in the café scene. In fact it's all over the film like syrup on pancakes. There's even a 1953 'girly' calendar, something which raises a 21st century eyebrow of disapproval. But what you can't disapprove of is its message. This is a recruiting film for a union (smack bang in the middle of the decade of McCarthyism!) and however simplistic, you have to applaud the argument and the aims. Remember Don Hollenbeck was a trusted broadcaster and was regularly attacked in print for his sympathetic regard of communism so this movie was a way to 'undemonise' the union's reputation and its tenuous relationship with the type of imaginary communism so feared by US politicians in the 50s.

"Winning through the democratic process!"

Far from the quality of the main feature, it's not been scrubbed up despite its 1.33:1, 1080p HD presentation. It also has sub-titles. It's filthy and less than sharp overall and grainy as hell. These aspects don't blunt its effect though but it's too earnest for me to choose to watch it for pleasure but it is a fascinating glimpse of a great director's evolution. The restoration was made by the Museum of Modern Art, a fact that raises another eyebrow. I guess it's a solid example of the recruiting film, an historical curiosity.

Flying Padre (8' 37") and Day of the Fight (12' 35")

I was lucky enough to have already seen these two shorts at a Kubrick weekend at Sussex University in my teens. My memory of them is fairly reliable as there were no shocks of "Oh, I didn't remember that..." on second and third viewings. Again, they are both products of their time and a startling lack of sync sound characterise both as well as an overabundance of orchestral cheese married to an earnest and patronising voiceover. Both were shot on 16mm film and are presented in the 1.37:1 ratio in a 1080p presentation.

Flying Padre is an RKO short made in 1951, an assignment won by Kubrick after he hawked his first film around the studios that same year, The Day of the Fight. In a 1969 interview, Kubrick called it "silly". Boy, was he right. Father Stadtmuller gives his parishioners the benefit of his services all over rural New Mexico by being a plane owning pilot. The 'padre' part seems immaterial. It's the plane that's the star, shipping off sick kids to hospital. Not sure the fact he's a priest makes any difference. Presented in 1080p, it looks awful, washed out and dirty. A curio, nothing more.

Day of the Fight is Kubrick's own production. It boasts up front "All events depicted in this film are true" which would have been extraordinary if it had featured something extraordinary. It doesn't. It's the short story of a boxer preparing for a fight. Wow! Hey, what am I talking about? My first film was about a friend of mine being run over by a moped. Raging Bull, this isn't. There are not even any sound effects laid over the punching! There is a shot very reminiscent of the famous scene in The Shining of Nicholson shot from the floor from inside the freezer room. By its nature (with Kubrick on his back shooting the boxers fighting above him) this is a staged set up. So much for the truth stated at the start.

Unlike the main feature, the subtitles on the two shorts are off centre and to the right. No idea why.

Video discussion of the film by critic and Stanley Kubrick author Bill Krohn (15' 25")

With clips of Fear And Desire liberally sprinkled in, Bill Krohn delivers his defence of the film in what looks like his study with a TV showing the movie silently behind him. It's one shot. I'm trying to be tactful here but I would hardly herald this feature for its visual nature. It's just Krohn standing there talking at us with no discernible editing – all the "uh"s and "um"s have been left in. It's all interesting stuff – great info on Kubrick's early years – but if you're going to include a visual extra on a Blu-ray of Kubrick's work, a little more imagination would have been welcomed. I suspect it was done in a hurry with little money. I'm all too familiar with that state of affairs. At 2' 33" in, there's a black and white self portrait of Kubrick at 24, presumably shot into a mirror. Here, he's the spit of George Harrison. At 7' 33", there's a poster for De Sica's Bicycle Thieves that is remarkable. It's marketed almost as a sex farce with the legs of a sexy lady swept up on a bicycle. I don't remember that in the movie. But sex was the only way to get anyone into an 'art' cinema according to the producer Joseph Burstyn. Don't get me wrong. This is a great extra for information and comment but I guess the filmmakers were probably given an hour with their subject, "Go Bill, talk!" and that was that.

Inlay Booklet containing writing on the film, vintage excerpts, and rare archival imagery.

The single essay in another fine accompanying booklet from Masters Of Cinema is by James Naremore entitled 'No Other Country But The Mind'. A professor at Indiana University, he presents the context in which the film was made, noting the changing nature of Hollywood at that time and detailing loads of additional information on the making of the movie. The essay is an excellent accompaniment to Bill Krohn's piece to camera with a little bit of repetition but mostly neat dovetailing. Knowing full well Kubrick's own fear of flying in his later years, I was startled to read here that he was a pilot himself in his youth. There is a director's statement which has to be read in context given the hugely critical quotes by Kubrick at the start of the essay and there's the obligatory "How to watch this properly!" page. Peppered throughout with archival stills from the movie, it's an attractive addition to the Blu-ray.

Well. OK. Uh... Fear And Desire is the work of a filmmaker in training. It's significant only that the particular filmmaker was Stanley Kubrick. I'm not cutting it any slack because of that salient fact but I hope the Blu-ray serves as the last jigsaw piece for lovers of Kubrick's astonishing body of work. I recommend the disc for the attention and quality of the restoration and to those whose Kubrick collections need closure. Odd film... Really odd!

|