| |

“Drugs are a waste of time. They destroy your memory and your self-respect and everything that goes along with your self-esteem.” |

| |

Kurt Cobain, singer |

| |

“I used to do drugs, but I'll tell you something honestly about drugs, honestly, and I know it's not a very popular idea, you don't hear it very often anymore, but it is the truth: I had a great time doing drugs. Sorry. Never murdered anyone, never robbed anyone, never raped anyone, never beat anyone, never lost a job, a car, a house, a wife or kids, laughed my ass off, and went about my day.” |

| |

Bill Hicks, comedian |

| |

“My daughter, Carly, has been in and out of drug treatment facilities since she was thirteen. Every time she goes away, I have a routine: I go through her room and search for drugs she may have left behind. We have a laugh these days because Carly says, ‘So you were looking for drugs I might have left behind? I’m a drug addict, Mother. We don’t leave drugs behind, especially if we’re going into treatment. We do all the drugs. We don’t save drugs back for later. If I have drugs, I do them. All of them. If I had my way, we would stop for more drugs on the way to rehab, and I would do them in the parking lot of the treatment centre.’” |

| |

Dina Kucera, author |

| |

“Fuck the drug war. Dropping acid was a profound turning point for me, a seminal experience. I make no apologies for it. More people should do acid. It should be sold over the counter.” |

| |

George Carlin, comedian |

These days, I don’t do drugs, at least ones that have yet to be legalised, but I’d certainly like to. When you spend most of each day dealing with different shades of pain, the very idea of getting out of your head and forgetting about it for even a few hours has phenomenal appeal. But in recent years, I’ve become so socially isolated that I wouldn’t have a clue where to get my hands on any. Worse than that, I’m out of touch with just what is being peddled on the black market these days and what their current street names are. I would thus be dangerously uncertain which them would lift me up and which land me in the emergency room. Some days, when the pain is at its worst, I figure it would be worth the risk either way. Hmm. I think I may have just written the quiet bit out loud.

There are a whole string of reasons why people take drugs, but easy availability and peer pressure both have to be high on the list. I was born too late to have even been aware of the late 60s counterculture scene, but had I been in my late teens or early twenties and on the right university campus, I have a feeling I would have spent half my waking hours tripping on acid or LSD. Instead, I became close friends with a serial drinker, and alcohol swiftly became my more legal drug of choice. Many years and a few mysterious bodily malfunctions later, I am now reliant on a daily prescription of tablets to keep my sometimes-crippling nerve pain under some sort of control. Is there a difference between dependence and addiction? I like to think so. A couple of years back, when I was clobbered by a mother of an inner ear infection that antibiotics initially failed to shift, I stopped taking the nerve tablets for a week and endured the pain instead, concerned that the first drug might be hindering the second. Had I been addicted, I could not have done that. Indeed, I’m fairly sure that it’s an fear of opioid addiction that has prevented me from taking the strong pain killers I’ve also been prescribed unless I absolutely need them. When that need arises, I sometimes combine them with more legal stimulants to get a small high. And you know what? Just for a short while, it feels great. Hence my opening statement.

Over the years I have tried a handful of illicit substances, only a few of which had the desired positive effect on me. I never stuck with any of them, in part because by then I had first-hand experience of where it could lead. For years, someone close to me, as nice a guy as you could want to meet, was hooked on a variety of drugs, progressing over time from those you snort to those you inject. He once became seriously ill will blood poisoning after sharing a needle, went to extraordinary lengths to get enough cash to afford his next fix, and ended up being raided by the Drug Squad for dealing after a few trips smuggling drugs into the country in swallowed condoms, any one of which would have killed him instantly if it had burst. Pleasingly, this story has a happy ending. Instead of continuing to feed his addiction while in prison, he used the time to get straight, and on his release became a successful drug counsellor. It worked out well for him. It doesn’t for many.

In the past, this was a subject that mainstream cinema just didn’t know how to handle. Drugs and drug-taking were for years primarily portrayed in an unforgivingly negative light, unsurprising in a time when films were made almost exclusively by middle-class, morally conservative white men, most of whom had long since kissed their teenage years goodbye. That a good many of them also smoked and drank is something we’ll let slide for now, but worry not, this will become relevant later. By the 1960s, cinematic depictions of addiction had come a long way since the demonising propaganda of the 1935 howler, Cocaine Fiends, with notable progress towards a wider public understanding made in 1955 by Otto Preminger’s ground-breaking The Man with the Golden Arm. But too often in mainstream cinema, drug addiction was employed as a throwaway shortcut to painting characters as criminals, hopeless losers or evil monsters. Attempts to understand the nature or – horror of horrors – the appeal of drug taking were as rare as crocodile pyjamas, as was the admission that many of those experimenting with illicit drugs were not societal dropouts, but the teenage sons and daughters of respectable middle-class families.

Then in 1968, acclaimed TV drama series, CBS Playhouse, screened a work written by J.P. Miller and directed by David Greene titled The People Next Door, and that particular bourgeoise illusion was spectacularly shattered. The play starred Lloyd Bridges and Kim Hunter as the parents of a teenage girl, played by the 14-year-old Deborah Winters, who is revealed not only to be sexually active, but a habitual drug user. The impact on the American viewing public was considerable, and two years later the decision was made to turn the play into a film for cinema release. Again written by Miller and directed by Greene, it featured a largely new cast, but retained the now 16-year-old Winters as the drug-taking Maxine. That it failed to have the impact of the TV original is hardly surprising – the play broke new ground, and two years on the story no longer had the shock of the new – but from a modern perspective it’s still an intriguing work, a time capsule record of the impact of radically changing times on the superficial stability and deceptive surface sheen of the American middle-class family unit.

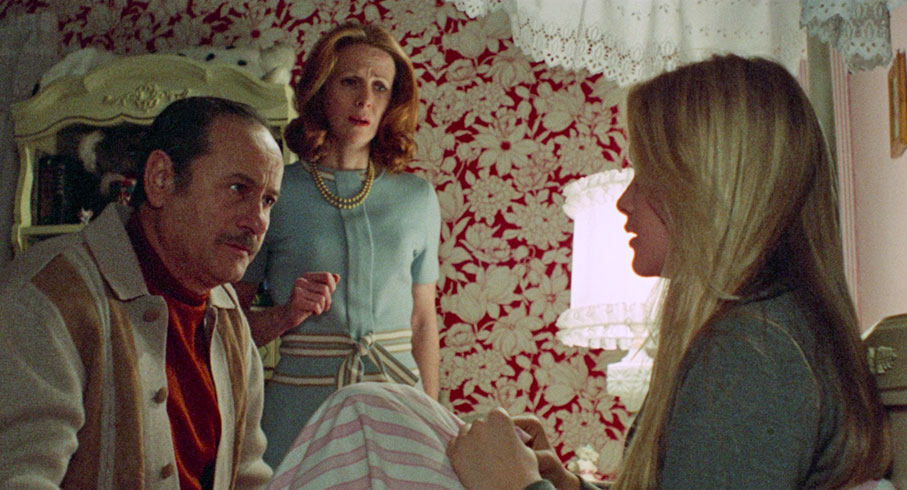

Early on in the film we’re given a handy reminder of one of the things that most outraged suburban American parents in the late 1960s, when cheerfully half-sloshed father and small business owner Arthur Mason (Eli Wallach) chides his bohemian son, Artie (a young Stephen McHattie, here making his big screen debut), about the length of his hair, and everything about how this exchange and its aftermath unfolds tells us that this is nothing new in the Mason household. Artie is an aspiring rock musician whose band we see auditioning during the opening title sequence for a contemptuous club manager whose principal complaint about the music is that you can’t dance to it. Artie’s watched as he performs by his younger sister Maxie, who that very morning had also irked her father by playing music loudly on her transistor radio as she cheerfully prepares to head out for the day. In common with so many of his peers, Arthur just does not understand these kids today, and seems to have a lot more respect for the more straight-laced Sandy (Don Scardino), the son of his neighbours, David and Tina Hoffman (Hal Holbrook and Cloris Leachman).

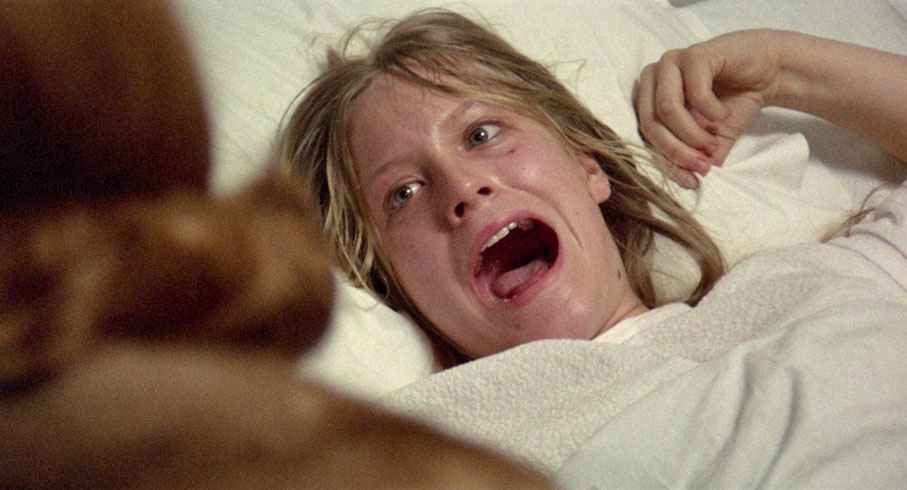

That evening, Arthur and his wife Gerrie (Julie Harris) are shaken when they discover Maxie in a closet in a state of uncontrolled hallucinatory distress. It’s Artie who twigs that she’s having a bad acid trip and he who knows exactly what to do to nurse her through it. Convinced that Maxie got the drugs from his hippie son, the outraged Arthur angrily frisks him and tears his room apart, and when finds nothing, he throws the already departing Artie out. “You’re not coming back here, for anything!” he barks at him as he leaves, adding threateningly, “If your sister suffers any kind of damage because of this, any permanent damage, you better start runnin' because I'm comin' after you, and I'll break every bone in your body!” With Maxie now sleeping, Arthur and Gerrie head out to talk to David, who as principal of the local high school is probably more knowledgeable on such matters then they are. When they return, however, Maxie has woken and reacts to the news of Artie’s departure by defiantly revealing that she has been taking acid and having sex for some time now, news that distresses Gerrie and dials Arthur’s fury right up to 11. But this proves just to be the start of this family’s problems.

In a sense, this is a template for many a drug addiction movie that followed, but what I’ve not touched upon in above is the relevance of the subtly suggestive detail, much of which is built on in the scenes that follow. Even as Arthur and Gerrie are first reacting with horror at the notion that their daughter has been taking drugs, for example, we’ve been dropped hints that they both have their own, albeit legal and socially sanctioned addictions in the shape of Gerrie’s chain-smoking and Arthur’s frequent drinking. When Gerrie pops next door to talk to David, meanwhile, the door is answered by Sandy, who reveals that his father has been called to the school because of a riot. He smilingly then says of his unconscious mother, “You know Mom, she gets kinda sleepy after dinner sometimes,” even though her position and the empty glass beside her tells a rather different story. When Arthur and Gerrie arrive at the school, they find it in a state of post-riot pandemonium, with rooms trashed, slogans daubed and the last of the rebellious students being rounded up by the police. What’s telling is the calm with which David is handling it, joking that the students somehow missed destroying the coffee machine with the air of someone who’s seen this all before more than once. Later, when we see David and Tina together, it’s clear from Tina’s unashamedly public displays of lust for her husband that booze is not her only addiction. The underlying hypocrisy of the adults’ condemnation is most directly exposed when Arthur and Gerrie throw a party for Maxie and her friends and make a genuine attempt to connect with this new generation, a social gathering at which the adults drink copious amounts of alcohol but from which a young man is angrily ejected by Arthur for smoking marijuana.

So commonly have the figures been quoted in the decades that followed regarding how much more destructive nicotine and alcohol consumption are than cannabis, extasy or many a casual drug of choice, that the comparisons made here may can seem a little obvious from a modern perspective. But back in 1970 I’m guessing this argument was still fresh enough to be curtly rebutted by the conservative establishment, and even today the debate tends to focus on the illegality of substances that are not subject to any safety regulations or quality control. Of course, the theory is that a dealer who wants to keep and even expand his user base is going to want to supply goods of a quality that will keep his customers coming back for more and not inadvertently kill them, but one looking to make a quick bit of cash and move on will likely have no such concerns. You may know a fair bit about your drug of choice, but not what it’s been cut with. And there’s a reason certain legal drugs still require a prescription to buy – like most people, if I get an infection then an antibiotic is the logical treatment, but if it’s Penicillin based, there’s a chance that it will swell my throat and cut off my airway. I somehow doubt a dealer would have access to my medical history, or care about it one way or another if he or she did.

It’s this potentially lethal risk that’s at the heart of the direction The People Next Door takes in its second half, as a particularly bad STP* trip sends a traumatised Maxie running naked into the street and ultimately results in a complete mental breakdown. Confined to a psychiatric hospital under the care of the calmly persistent Dr. Salazar (Nehemiah Persoff), Maxie is reduced to an uncommunicative shell of her former self, the emotional impact of which devastates her family and results in the severely depressed Gerrie refusing to leave her bed. By this point, Arthur and Gerrie’s lives have already been turned upside-down by the revelation that Arthur has been having a long-standing affair, something publicly exposed by Maxie in a frankly unhelpful-looking group counselling session. Gerrie’s weary admission that she has been aware of this for some time paints her earlier verbal battles with Arthur in a rather different light and taints their relationship from this point on.

Structurally, the key groundwork of The People Next Door is laid by J.P. Miller’s screenplay, which although ultimately sides with the ‘drugs are bad’ viewpoint and has its share of uninspiring dialogue, does make what for the time was a bold attempt to grapple with the impact of addition on the average family and not paint the parents in idealistic colours (major spoilers ahead – skip to the final paragraph to avoid or click here). Here, almost no-one is who they seem to be: the loving father is a heavy-drinking womaniser; the mother is a chain-smoking manic-depressive; their pretty young daughter is a sexually active drug-addict with a grubby biker boyfriend; the hippie son shuns drugs and has repeatedly tried to dissuade his sister from using them; and the real bad guy turns out to be the seemingly straightlaced son of the school principal next door, an amoral opportunist who peddles a wide range of narcotics to a new and eager young market. It’s with this revelation that the multi-layered nature of the title comes fully into focus.

The casting and performances are top-notch across the board. Eli Wallach does a lovely line in irritable and sometimes volatile tolerance in the early scenes, while his explosions of anger, bouts of self-centred annoyance (his tetchy delivery of the line, “You do that…” when Gerri announces she is going next door to seek advice from Davis says so much them both) and frustrated attempts to come to terms with this new reality are always convincing. His very real shock and disgust when his drugged-up and naked daughter kisses him passionately on the lips – a genuinely startling moment in a film of this vintage – is a memorable highlight. As Gerrie, Julie Harris is saddled with the film’s most blatant legal addiction and is rarely seen without a cigarette in her hand, but still does a sterling job of conveying Gerrie’s distress and confusion, and her calm admission that she’s known for some time that her husband has been playing around, strikes just the right note of weary acceptance. The ever-effective Hal Holbrook really comes into his own in a superb display of suppressed fury as David when he discovers that his son is the dealer who has put his good friend’s daughter in hospital, and as his amorous wife, Tina, Cloris Leachman makes for a most convincing middle-aged sexpot, one who is nursing her own set of suppressed insecurities. I really liked Stephen McHattie’s portrayal of Artie, which kicks against the 60s movie hippie clichés on all levels and makes him the film’s most easily likeable character, but shining brightest is the then 16-year-old Deborah Winters, who comes close to stealing the film as Maxie. She may come across as self-centred and deliberately destructive at times, but Winters’ performance is searingly impressive throughout, never more so than the moment when her face contorts into a tortured and terrified silent scream at the sight of her mother when first visited by her in the psychiatric hospital.

The People Next Door is a sometimes uneven but intelligent, impeccably acted and – for the time – important work, even if this feature adaptation was – by virtue of being a remake of a TV play that was widely celebrated for breaking new ground – a little late to a party that by 1970 was in full swing. David Green directs with purpose and a pleasing absence of show-off flash (a brief POV shot seeing through Maxie's prism sunglasses at the start fits the tone of the scene), making particularly effective use of facial close-ups at key dramatic moments and letting the camera follow the drama instead of shaping it. The film also benefits from a couple of rather decent prog-rock songs by the short-lived band, The Bead Game, who even make an appearance as Artie’s band in the opening scene. If there’s a weakness – and this is going to be a matter of individual opinion – it lies in the more hesitant aspects of parallels drawn between the illicit drugs taken by Maxie and the legal ones her parents have been using for years. The hypocrisy of this is made clear, but there is still a delineation, with the cigarettes and booze on which Gerrie and Arthur are seemingly dependent not ultimately shown to have any detrimental effects, almost coming across in the process as a safe alternative to the likes of acid and STP. Boy, would that change. That doesn’t alter the fact that The People Next Door is compelling as drama and effective as a film, and its portrait of this little piece of the late 60s counterculture is one of the most grounded and believable you’ll find in American mainstream cinema of the period.

Sourced from a 4K restoration from the original negative by StudioCanal, the 1080p transfer, framed 1.85:1, nicely reproduces the film’s grittily realistic visual style, with well-balanced contrast, solid black levels and colour palette that favours earthy hues but still handles brighter, pastel-leaning colours well when they appear. The grain is very visible but appropriate to the film’s chosen look, and thesharpness and detail are very good on close-ups and only seem to soften a tad on some of the wider shorts, but again this feels right for the realist aesthetic. The image is free of dust and damage and sits solidly in frame with not a hint of jitter.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack has the expected slight restrictions in range, but is otherwise clean and clear, with always audible dialogue and decent reproduction of the prog-rock music.

There are optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired if you need them.

Audio Commentary with Rutanya Alda and Lee Gambin

Here, ever-enthusiastic film historian Lee Gambin teams up with actor and fellow film historian, Rutanya Alda, who has a small role in this film as a flirty nurse, an interesting bit of character business that apparently came about due to a suggestion on her part. There’s a lot of ground covered here, including why adults of the time felt so threatened by the hippie counterculture, how Maxie’s first trip almost moves the drama into horror film territory, why Maxie is not a particularly sympathetic character, how the addiction of the daughter is reflected in the habits of her parents, and more. There’s plenty on the actors, including Alda’s recollections of working with Julie Harris, a too-brief mention of her work in early Brian De Palma films, and an interesting tale of the one time she did give acid a try. The only time my eyebrows raised a little came when they started wondering what a pretty girl from a nice home thought she was rebelling against by taking drugs. Seriously? Were these people never young? Intriguingly, a short while later they seem to answer their own question. Really good stuff, nonetheless.

Deborah Winters: Tripping with Maxie (38:33)

Before I get started here, I will mention that I was initially thrown by the oddly upward-looking framing, the slight image softness and the blurry motion of this interview, at least until it dawned on me that it was recorded from a call made on Skype or similar, a forced compromise due to problems caused by a certain global virus. Although she’s apparently since abandoned acting and moved into real estate (I learned this from the commentary track), Winters is still happy to talk about her earlier career and her key role as Maxie in The People Next Door. Of particular interest are her memories of working on the original CBS TV production, which are illustrated with cutaways of related newspaper TV guide pages. She recalls loving making the film and has specific memories about each of her principal fellow cast members, though now regrets being too young to appreciate the mine of experience she could have drawn on by talking to them about their careers. She confirms that there was a body double for the nude scenes – unsurprising given that she was just 16 at the time of filming – but also that her grubby boyfriend in the film was played by a real Hell’s Angel and that the institution scenes were shot at a functioning psychiatric hospital. A really interesting inclusion.

Brian Smedley-Aston: Structured How to Feel (9:15)

Also Skyping it in is Brian Smedley-Aston, who edited the film but was credited as supervising film editor to conform with local union rules, which is why the credited editor, Arline Garson did no actual work on the production. He recalls meeting director David Greene and working with him on The Shuttered Room, Sebastian, and The Strange Affair, a film that haunted me in childhood that I’ve frustratingly not seen since. He talks a little about a disagreement between Greene and the producer (he doesn’t name him, but I presume we’re talking about Herbert Brodkin) that nearly saw him and Greene walk and did ultimately result in some changes to the editing. He also admits that the film didn’t have the impact of the earlier TV version, neatly describing it as a good movie that came too late.

John Sheldon: My Life in Review (14:44)

Guitarist with late 60s prog rock band, The Bead Game, whose music is featured in the film, recalls (also via a video link) working with Van Morrison when he was 17 but parting company because he was getting louder just as Morrison was getting softer. He outlines how the band was started by Robert Gass at Harvard and how he joined later after responding to an ad in a pizza shop. He reveals that when they were recording their only released album, Welcome, they had the studio until midnight, when Jimi Hendrix would come in and record in it until dawn. There’s quite a bit more, all of interest.

People Person: Vic Pratt on David Green (18:39)

The only professionally shot interview on the disc features film historian and Indicator regular, Vic Pratt, who here provides a comprehensive and frankly fascinating look at the career of Manchester-born director, David Greene. He covers his early life and career, his move from acting to directing and his acclaimed television work, where he became the first British director to win an Emmy. His eventual dissatisfaction with the Hollywood lifestyle and fascination with the neo-realist films coming from Europe saw him sell up and move back to the UK, which led to more TV work both here and in the US, and eventually a move into dramatic features, each of which is covered in considerable detail. A really informative extra.

Image Gallery

33 screen of monochrome and grainy colour promotional stills, lobby cards, press notes and posters. I do like the cheek of a tagline that describes the film as, “A trip in the suburbs, among all those trees and all that grass.”

Booklet

The lead essay here is by film writer Peter Tonguette, who makes a solid case for many of the film’s considerable virtues, as well as having a small dig at some of its weaknesses. Next are some of the rave reviews, plus one whose writer wasn’t so enamoured, that appeared following the screening of the original CBS Playhouse production. A 1969 press conference interview with Eli Wallach conducted by Earl Wilson is next, where Wallach talks about his career and his marriage to fellow actor Anne Jackson – his upcoming role in The People Next Door also gets a brief mention. Following this is a brief but interesting piece on the soundtrack album, after which are four contemporary reviews – there are positive words from Richard Combs in Monthly Film Bulletin, but the American critics are less complimentary, the key complaint being that the subject matter has dated in the two years since the small screen original. Credits for the film and publicity imagery have also been included.

It may feel just a little ragged in places and its impact has obviously been dulled by the passing of time and some excellent film studies of addiction made since, but The People Next Door is still a gripping, well-acted and unusually objective look at a still-touchy subject, one I’m happy to see get such a quality Blu-ray release. In an ideal world, we’d have a two-disc set that included the TV original, but the complexities of rights ownership and licensing make that an unlikely prospect, and this disc, with its fine transfer and strong collection of relevant special features is still another win for Indicator. And yeah, you don’t have to have taken drugs or dealt with addiction to appreciate the film, but it probably helps. Warmly recommended.

|