|

DISC 9

| Psy-Warriors (1981) |

Camus |

|

| |

"I saw Psy-Warriors and I said to Alan, "That's a right wing film, as far as I can see. You're softening us up as a public. You're not exposing anything, you're just making it OK for them to do it. We were being educated to accept this, not to fight it." I don't think he agreed with me. But he didn't say anything – funny bloke, quite sensitive in some ways." |

| |

Cameraperson, Grenville Middleton |

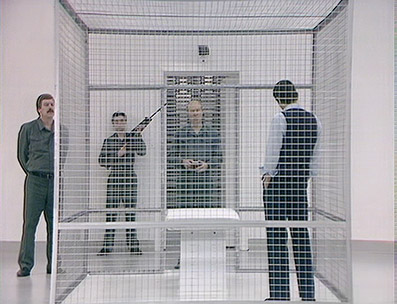

Clarke is the director least likely to hold an audience's hand. I'm pretty sure he wasn't afraid to give us information when necessary but some advice; I know he's not with us anymore but just as an idea, never ask Alan Clarke to teach you how to swim… You know where you're going to end up, spluttering, thrashing and terrified. The film starts with that ludicrous, screaming interrogative behavior that someone, somewhere signed off on as being a good way to break down the enemy prisoner. It might be. I'm fortunate enough to not be on either the receiving or giving end of such behaviour. I edited a documentary about sleep deprivation a while back, which was absolutely fascinating. Denying prisoners a regular sleep pattern (interrupt deep sleep, keep them awake) was one of the most effective ways to really screw with someone's head and get defences down to zero. Throughout the first half of Psy-Warriors, you're left unsure how 'real' this interrogation is. Bearing the brunt of Warren Clarke's screaming lead torturer is John Duttine playing bomb suspect Nigel Stone. Stripped naked, hosed with cold water and made to stand in hugely uncomfortable positions, the actor's dedication is evident. I'm assuming even torturers have to keep their captives alive in some fashion and Stone is force-fed a sandwich and given water in as long as it takes for him to swallow. It's a surprise to those of my generation to see the stuttering 'Yes' man from The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin playing such a role and being damn fine in it. "Super!"

The film follows the fate of three suspects as their captors try to force confessions out of them or just mentally and physically torture them demanding nothing but compliance in return. You're obviously reminded of Guantanamo and the shocking treatment of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib but remember that Clarke's film was made in 1981. It's hard not to think of the famous Stanford Prison Experiment in which students volunteered to play prisoners and guards over a period of ten days. In a frighteningly short space of time, primal emotions took over and the experiment had to be abandoned due to the perverse negative psychological effects some students experienced. Halfway through, the film takes a turn, which I won't reveal but we are led down a much murkier path debating the wisdom of such behaviour and whether it can ever be warranted. As ever, the higher brass, staying well above the violence by dint of rank and privilege, sit in comfortable chairs discussing the advocacy of such practices. When Warren Clarke suddenly starts speaking in a normal tone of voice debating with his superiors, it's more of a shock than some of the violence meted out to the prisoners. Derrick O'Connor plays the smart-ass, mouthy captive Richards, the first to argue with his guards and the lawyer Northey is played with calm authority by Colin Blakely. Their exchanges are priceless debates on the ethical boundaries the army are willing to stretch and break. Again, this is a David Leland script and the film's dialogue bristles with unanswered questions, questions the film asks its audience to wrestle with. This film was from an age when television was relevant tackling issues that no other medium was taking on. You just get the tremendous impression that people like Leland and Clarke cared so much about the society they worked in that they pushed boundaries that, in their own small but important way, made us better as human beings; and if that sounds pompous or too grand a claim, live with it.

The film features the very famous newsreel from the Vietnam War of the prisoner marched forward and coldly shot in the head. Its reality brings you up short and I'm assuming its inclusion was fiercely debated. When it aired, it was moved forward an hour (just to be on the safe side?) If there's one place Clarke never lived, it's on the safe side. Clarke credits producer June Roberts for having the bottle to get it made and broadcast. Bravo, June. The film was shot mostly in a studio, formally framed, lit harshly and it included some shots that show up a decade later in Frank Miller's graphic novel Sin City and subsequent movies. I'm not accusing Miller of ripping off Clarke. I'm just making the point that similar creative choices were arrived at by two men I consider very highly. Did I get away with that? Clarke's framing choices are very precise with a very structured 'mise en scène' and its framing is often symmetrical and unmoving as the sadistic treatment is meted out. To cover this sort of drama in the modern context of jittery camera and close ups would have missed the point entirely. This is a dispassionate look at a subject that needles and rips at the very heart of a democratic society. How nasty do we need to be to keep civilisation on track?

There were two aspects of Psy-Warriors I flagged as not working as well as they might (for me, you understand). The first and least important for a TV film is the title. It's an ungainly name that doesn't reflect the film at all. I know the 'Psy' is short for psychological (duh) but it doesn't mesh with 'warriors' at all and these soldiers are not warriors in any real sense. I'm sure Leland would argue his case, and stripped naked, deprived of sleep and hosed with freezing water, I might capitulate. I may be just reacting to the uneasy marriage of that odd prefix and the odd word. They just sound wrong together. You need a title that says 'How far can a just society go in breaking its own rules to maintain its own security and civilisation?' Granted, it's not a sexy title even for TV where you have a captive audience. I might have gone for something like; Out of Line, Beyond the Line, Breaking the Line or Crossing the Line (to bring it back to film technique). It's a tough one. Try The Pain Centre or The Pain Principle, a riff on the Freudian theory. Apologies for going on but that original title wound me up.

Secondly and more importantly, there is a performance in the film that stands out for all the wrong reasons. Rosalind Ayres is a gifted actress who has enjoyed a varied career on stage and screen but despite her performances (one in of all things Titanic), I didn't feel that her mannered testiness gelled with what was happening to her and her comrades. As Turner, she plays her captive role as an indignant schoolteacher from the Home Counties and her attitude never truly convinces. I can't figure out if it's her accent, dialogue, the way she was directed or the choices she made but the indignation is not strong enough to convince me that here is a vulnerable human being inside trying to hold on to some semblance of self-possession. She and Richards get some harsh treatment but for those two of the three, it's mostly a battle of wills. Ayres is a fine actor. I just feel that more steel and less prickle would have served the character better.

These small gripes aside, Psy-Warriors is riveting television. This box set, a time capsule from the golden age of the glass teat, should not be a diamond in the rough and that's a small but telling tragedy. Like the Apollo programme, it feels like we'll never rise to such heights again, mired in the mundanity of mindless wallpaper that seems to constitute mainstream television these days (with a few very notable exceptions of course).

Bertolt Brecht is one of those revered writers whose very name can trigger a critical highbrow alert. Having only seen a couple of the author's works – this being the second, The Caucasian Chalk Circle was the first – I'm not in a position to compete with these more learned lords of theatre criticism, or offer an even half-baked definition of what the term 'Brechtian' actually means. I thus have to take the work as I find it, and by thunder I loved this production of his first play, Baal.

For those as new to the play as I was when I first saw this made-for-TV version many years ago, the titular Baal is a poet and singer of some repute, but is equally renowned for his drunken womanising. A determined outsider of scruffy dress, unkempt hair and nicotine-stained teeth, he is courted by the bourgeoisie for his talent and notoriety but held in contempt by those who believe he is socially beneath them. He certainly seems happier when drinking with or singing for the proletariat, which doesn't stop him carrying on an affair with his publisher's well-to-do wife, Emilie. He fails to change his ways when he hits the road with his friend Eckart, but his debauchery and disregard for the feelings and welfare of others look set to bring him down.

In what at the time must have seemed like stunt casting, Baal is played here by David Bowie, but if this prompts you to let out a snort of derision, then you should see what he does with the role. Bowie made his mark in a number of screen roles over the years, but never was he better than he is here. And this is not a case of a singer holding his own in an acting role, but one who invests every inch of himself into the character and it's all up there on screen, in his line delivery, his playful inflection, his body language and his facial expressions, from the looks of amused contempt he throws at visitors to his scraggy abode to the fierce threatening glare he aims at Eckart when he attempts to grab a hat that Baal is sitting on. There's an electrifying truth and magnetism to Bowie's performance here that stands in direct contrast to the more theatrical turns of the other cast members (we'll make an exception of Zoë Wanamaker's captivating performance as prostitute Sophie). On the basis of Clarke's repeatedly demonstrated skill at getting the best from his cast, we can presume this was a deliberate ploy on his part to endear us to an anti-hero whose callous and selfish nature are made oddly tolerable by his rebellious nature and willingness to bite off any hand that feeds.

There's a fascinating dichotomy to Clarke's direction here, which alternates between the classical and the experimental. Whole sequences are framed in painterly wide shot and lit in a manner that, had this been shot on 35mm film, would probably still be celebrated for its striking visuals, something the comparative harshness of analogue video can't help but undermine. Elsewhere he rejects realism completely and embraces the avant-garde, creating diptychs with a painterly freeze frame in one panel and Baal acting as a musical narrator in the other, or having Baal and Eckart walk and talk across a bare studio floor adjacent to a simple painted representation of the landscape they are theoretically traversing.

Baal is a consistently rich and rewarding achievement which pays close attention to detail on every level – the production design, costumes and makeup are all first class – and would prove an excellent introduction to the work of its celebrated author. It's one of my favourite films in this set, and for Bowie's delicious performance alone rewards multiple viewings.

Initially I tjought we had been sent these two titles on DVD rather than Blu-ray due to a shortage of Blu-ray review discs, but I have since been informed by the BFI that even in the Blu-ray release of this set, these two films will be available on DVD only. Though I've yet to confirm the reason for this, I'm assuming that the only working copies of both were in standard definition and that mastering either on Blu-ray would thus be redundant. I'll update this review if I confirm this either way.

That said, the results are still impressive. Both Psy-Warriors and Baal were shot in studio conditons on analogue video and both look pretty darned good here. Clarke's instruction to his lighting crew to flood the white-walled main set of Psy-Warriors with light gives the piece a chilling sterility that is very nicely captured without any hint of burn-outs or over-exposure (check the screen grabs above, which are from the DVD), and even the darker scenes are cleanly rendered with a strong level of detail. Baal goes the opposite direction in favouring dark-coloured sets and more classic, high-key lighting, but here also the detail is very good and the contrast well picthed. The black levels do soften a tad when the light levels really drop, but this is par for the course on analogue video. Oh, if Baal had been shot on film... Conversely, Psy Warriors is perfect material for the immediacy of video.

The soundtrack on Psy-Warriors is very well recorded and mixed, and the sound crew would have had a hell of a challenge here, with quietly spoken sentences alternating with loudly barked orders, none of which distort. Baal is also well recorded and particularly well mixed, being one of the livelier soundtracks in Clarke's oeuvre, from the tavern crowd bustle to Bowie's songs (yes he does get to sing – the songs were in the play), all of which are clearly and cleanly reproduced here.

Alan Clarke: Out of His Own Light (Part 9) (19:08)

In the first third of this segment of the Clarke documentary, David Leland talks about how Psy-Warriors came about and went into production, Clarke's specific instructions for how it should be lit, and the absurd reaction to it when was coincidentally screened on the night IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands died. The final two thirds are given over to playwright Simon Stephens, who delivers a passionate and frankly wonderful appreciation of Baal, his opening line an excited, "David Bowie in Bertolt Brecht's Baal by Alan Clarke? What kind of utopia is this?" He surprises by stating that in his view the play doesn't really work on the stage but succeeds handsomely here, then pays tribute to the performances of Bowie and Zoë Wanamaker and to John Willet's translation, and suggests that there is "something haunting and muscular about this film." If you hadn't already watched the play in advance (and you really ought to), this would have you slobbering to see it.

DISC 10

| Stars of the Roller State Disco (1984) |

Camus |

|

| |

"Where am I?"

"In the Roller State Disco…"

"What? In the what? What do you want?"

"We want you to skate about until a job comes up."

"Uh… OK. Whose side are you on?"

"'Not yours, matey!' would be most accurate…" |

| |

|

Imagine The Prisoner, Patrick McGoohan's seminal series on dissent and rebellion. Replace the Village with a junior Rollerball set. Every character has numbers and there's a No.1 or Big Brother presence in the form of Christina Greatrex on screen throughout. Faux smiles and state sanctioned bonhomie infest this drab, dreary area and I neglected to mention three details. Almost everyone is an unemployed teenager and for reasons beyond my stuttering comprehension, low-grade disco music is piped everywhere and everyone's on roller skates. OK, so maybe roller discos were popular in the 80s but I never saw one (I just wasn't invited to those sorts of parties). But then wheeling around in circles was never a hobby I pursued with any enthusiasm – just like these kids. The exits are not guarded by large sentient weather balloons but by tall men with hi-vis vests (and then not exactly stringently). Sex is confined to the boiler room and 'successful', 'escaped' teens appear on screens as adverts for the lie of the abundance of opportunities outside. Their fake fervour fools no one. I may have to bite down on a mouthful of Imperial Leather but some of the acting on display is laughable. The whole enterprise feels like a large student project with all the students promised a part. Michael Hastings' original screenplay has been deadened by the relentless, motiveless movement and cloying music. If there are dramatic peaks and troughs, they've been hammered out by an insistent drum beat and a witless, ever circling bunch of youngsters who seem to be roller skating because some chap with a flat cap told them too, and no other reason.

Around about the same time in the mid-80s, the BBC's The Young Ones was broadcast. In a small surreal insert, Ben Elton appears as a 'teen' broadcaster dancing to a beat while presenting an odious 'teen' programme 'Nozin' Around', something congealed by middle aged, middle class minds. In fury, Rik kicks the TV in screaming "Did you see that? The voice of youth! They're still wearing flared trousers!" Well, if an Alan Clarke TV studio bound drama can remind me of 'Nozin' Around' then either I'm in big trouble or it's not Clarke firing on all cylinders. The drama is an unsubtle satire of Thatcher's UK after her second landslide victory in 1983 despite having polarised the country. Unemployment was at record levels and maybe on paper, the drama was sound. There's a germ of an idea in the lives of Carly and Paulette (Perry Benson and Cathy Murphy), the primary couple and their relationship, their uncertainty and desire to get out of what is essentially a forced labour exchange ('camp' would also be appropriate). On skates. And that's the USP but it's also the problem. It's extremely difficult to take anything seriously when someone's skating. Ask anyone who's seen the Wachowskis' hero from Jupiter Ascending… If Torvill and Dean gave the Gettysburg Address while Bolero'ing, there'd still be slavery today. There is a small thrill to be had to remember that their greatest moment was in the year 1984…

BBC science fiction in the 70s and 80s is usually synonymous with cheap. There's no getting away from the impermanent, flimsy constructs of studio sets and the glare of a reflected light in a shiny surface betraying the programme's low threshold videotape recording media. You have two mighty elements that can fight against the disbelief those first two negatives propagate: Script and performance. A great script or great ideas in a great script can render wobbly sets and stray lighting superfluous. In the heady days of Blake's Seven, it was the characters and the acting that held the attention – the human being. Give a great actor a great script (and let the director be in tune with both) and it matters little if the background is a piece of blue scrim with 'CSO BG TBA'* stenciled on it. Alas, Stars of the Roller State Disco is not crammed with interesting characters played by very talented performers and besides as I mentioned, all the nuance and subtlety (if there was any there) is wiped out by the endless circling and bass thumps. It's like trying to crochet in a wind tunnel. Let's just say that before this production and after it lay some of Clarke's greatest achievements. He's allowed a day of rest.

*Colour Separation Overlay Background To Be Allocated

| |

"I was tired, and Alan came to me and said, 'Look, Sean, you're a terrible fookin' actor. But if you let me in, we can make some -thing of this. You see, I don't want this to be a film about the army, alright?' I say, 'Ah. Right!?' He said, No, I'm not fookin' interested in the army, it's full of idiots. I want you to be this officer in this situation, Seany. If you were leading the Paras in South Armagh, how would you handle it?" |

| |

Lead actor, Sean Chapman |

Well, this one's a jaw dropper and it's certainly up there with some of Clarke's best work. Ostensibly Contact is a simple film following an army patrol on the Northern Irish border as the soldiers oust gun runners, clear booby traps and deal with the enormous stress knowing that at any moment you could be in someone's firing line or six foot in the air and in serious trouble from being too close to an exploding bomb. What Clarke manages to show us in between the sprockets of tremendous stress and sometimes-unbearable tension, is the utter and complete deconstruction of a man. Sean Chapman is a familiar face in both Clarke's oeuvre and on UK TV generally. But actors rarely get to eat prime-time steak and Chapman takes his opportunity with an understated gusto (is that even possible?) He makes us believe we are witnessing a man falling apart one tentative footstep at a time. Once he saw the finished film, I bet Tim Roth (first offered the role) was gutted but his wife was expecting and both he and Clarke knew that his place was at his wife's side. She gave birth after the production wrapped. On such vagaries of timing are careers made and unmade (not that Roth suffered any negative effects on his varied and hugely interesting career).

Chapman has the swagger and command of a man with many young lives under his charge (and boy, they are all so young which I assume is factually accurate) and his hand signals that take the place of nearly all the dialogue are eerily convincing. Writer Tony Clarke (no relation) was on hand during the shooting to keep an eye on authenticity having served as a Para himself. I know Chapman as a stalwart of the British acting establishment (Hellraiser put him on my map) but under director Clarke's relentless pressure to 'let out the pig', the unforced reality of truthful performance when gifted actors appear to do very little for maximum effect, his actor status is completely submerged in a true powerhouse of a performance mined by a director knowing exactly what his cast were capable of. Clarke's statement, "If you let me in…" is the precursor of the very quintessence of great film direction.

Imagine the Irish countryside, the rolling green hills, intoxicating beauty at every turn and at every one of those turns there's a gun or bomb about to be brought into play. As an audience member, you're on the edge of your seat from moment one. The behaviour of the cast tells you that this Elysium Field is a war zone and its staggering ordinariness is key to feeling the danger ever more keenly. Once you know what's possibly lurking around a corner or contained within the usually innocuous sight of a tree or parked car, your nails are going south. When a character dies from a bomb blast - and I can't confirm exactly what I was watching because Clarke never spells anything out which is as it should be - his tattered remains are ransacked by Chapman for ammunition that may well be used against them at a later date. To my small credit, this was written before hearing the commentary but that's all the trumpet blowing from me. This is, after all, Alan Clarke's party. It's the matter of fact way that Chapman performs this grisly deed that makes it all the more shocking. Confidence low, the team retreat to their digs, numbly affected by their comrade's death. Chapman, who needs his men (boys?) operating at peak efficiency says "Jackson's dead. It goes with the job." The line seems to be delivered at himself as much as his crew but it's clear from this extraordinary performance that Chapman is not only affected but profoundly affected by the loss.

Throughout the missions, the men come across a great many stressful scenarios and some of the patrols are at night. Clarke covers these moments through an army image enhancer, lending the whole frame a greenish hue. It's easy to forget that these scenes were performed in near pitch black and when Chapman and his crew come across a tent, we have little time to prepare for the worst. Inside are camping children oblivious in sleep to the role they may go on and play in the future of the 'troubles'. But there's also childhood innocence here and as Chapman and one of the children exchange a look (which is nothing of the kind from the child's point of view as she can see no-one in the pitch black), you're aware of a profound gulf between two human beings and how a short physical distance between them – and not that many years - can represent an abyss of difference in belief and world view. Abject cynicism has never failed to infect those constantly forced to wallow in the worst of human behaviour. It surprises me that more lawyers and judges are not turned to psychopathy given their daily diet of depravity and the very worst of our primal instincts.

There is a blink and you'll miss it moment that is as moving as it is fleeting. One of the men (another Clarke regular, John Blundell) sticks his head into his commanding officer's pokey room after the bomb incident and simply says "Don't get involved Boss, it's bad for the brain." This is masculine empathy hidden behind macho bluster that reveals a bond that cannot be exposed in the company of soldiers in any other way. And I'm writing this from the perspective of someone who still scratches his head watching the physical love-ins that seem to happen after footballers score goals. It's as if men have had their softer sides ripped from them and only on this literal field can they release strong emotions. Blundell's remark is as close to an admission of support and even affection that anyone in that situation would dare exhibit.

The last moments of the film will stay with you for a long time and you may start looking at the most innocuous objects a little more suspiciously from now on. Contact is one of Alan Clarke's small masterpieces of character and dare I say action that deserves far wider recognition. Hell, this should be on a fecking school syllabus somewhere.

Stars of the Roller State Disco is a studio shot, analogue video production and really looks it, having that specific look that I instantly associate with 80s UK television. There's a golden hue to the colour that seems to be down largely to the lighting in the skating arena (this is not a place I'd want to eat and keep my lunch), but is certainly lively when it needs to be. The contrast is punchy and the detail good. The sound is clear but that treble bias does give the dialogue a crispiness that really registers if you have the volume up high.

Contact was shot on location on 16mm, often in available light so that the camera could have 360 degrees of coverage, which does result in some punishing shadows and sucked-in detail when the light levels are low. But Contact is also a prime example of how such limitations can work for the film, giving it the utterly authentic look of a documentary and adding to the sense that what is happening on screen is how it really plays out. Yes, there's visible film grain and yes, there's an earthy tinge to many scenes, but it works so well for the film that I wouldn't change a thing. Even the image-enchanced footage feels like the real deal (which it was, of course). The sound may not have that pristine studio clarity, but once again it feels absolutely like it was grabbed on location by a sound operator with a boom mic and a keen sense of self-preservation.

Sean Chapman and Alan Bairstow commentary on Contact

This is a belter. Bairstow obviously is overflowing with genuine regard and enthusiasm for this film (I wonder why?) and he engages Sean Chapman throwing out enough admiration for even the least confident actor to be feel at ease. Luckily, Chapman is confident, easy on the microphone and shares Bairstow's enthusiasm and the pair click very satisfyingly. I'll not exhaust you with a breakdown of the commentary's contents as there's enough here to entertain the most casual fan. But I must mention a few snippets.

Chapman was often accosted after the broadcast by the real thing, Paratroopers who'd served, and they were complimentary about his performance and the reality of the entire film. That must feel good. Chapman bemoans the lack of time for rehearsals these days (a common and justifiable complaint among the acting profession there days, one that Janine Duvitski echoes in her commentary for Diane). When Contact went out, some people believed it was a documentary as the performances and camerawork tended towards that reading as well as a lack of anything dramatic happening in long stretches, periods that ratcheted up the tension almost agonisingly). Chapman mentions his character's isolation and his inability to sleep and he name-checks the Conrad novella Heart of Darkness. In 1984, Chapman and co. were only five years down the line from from Francis Ford Coppola's interpretation of the celebrated work, a little film called Apocalypse Now. Going in, the meaning of the word 'contact' wasn't explicitly clear to me – military engagement with the enemy – and I'm glad the commentary cleared that up.

Now let's look at the most controversial aspect of the film from a creative point of view. The first scene has always bothered me for a very specific reason and I'm glad to learn I'm not alone. In the extraordinary opening, a Para Regiment border patrol stops a car and a second or so after an unintelligible scream that could have come from anywhere, Sean Chapman's character shoots the car driver in the head resulting in the requisite splash of blood. This must have been something of a shock for TV viewers in the 80s. Now, I'm old enough to know that encounters like these at that time in that place were always highly dangerous ones, fraught with the bubbling threat of violence. So I made an assumption to get my moral compass pointing in the right direction. I assumed (steady, steady…) that the man shot was wanted and the fact he was murdered was summary justice, Northern Ireland style. Nope, I was wrong but it's hardly my fault for that reading. Ninety-five per cent of an audience will assume that Chapman's character has murdered a man. Clarke, notorious for feeding his audience scraps at best when it comes to understanding, doesn't make clear the two words you'll need to understand to 'get' why the man was shot. Sub-title readers would be way ahead any of us reliant on just the sound. The key, of course, is that 'unintelligible scream' I mentioned earlier. In the commentary, Bairstow (who primes us to listen carefully at the start) reveals that the pre-shooting line consisted of two words that gave the commanding officer full permission to fire his weapon. Listen out for it again. Seeing the driver with a weapon, one of his men screams "Gun, Boss!", Intel enough to get a man killed on the spot.

Chapman and Bairstow tells us that years earlier Clarke had got his hands on a Steadicam and in the later eighties, he would use one again but for Contact he either made the artistic and aesthetic choice of forgoing the smoothness of the device lapsing into faux-documentary hand held work (which is terrific by the way) or he simply couldn't afford one. Regardless of the reason for the choice, the hand held work is exemplary and you are never taken out of the drama by being made aware of the craft. This is a movie whose edges do not need softening. You almost expect to hear the cameraperson's keys rattling in his/her pocket (in this case it was Philip Bonham-Carter, no relation to the other famous Bonham-Carter, Crispin).

All in all, it's a wonderful commentary chock full of detail that fans of Contact could find nowhere else. Having said that, actress Janine Duvitski's partner in her commentary for Diane is Richard Kelly, editor of Alan Clarke, the book from where most of us get our Clarke info.

AFN Clarke on Contact (22:16)

Former soldier A.F.N. Clarke, author of both the Contact screenplay and the book on which it was based, is interviewed by his wife Krystyna, who cheerfully asks questions in brightly lit cutaways. Subjects covered include his first meeting with Alan Clarke (whom I'll refer to as AC here to avoid confusion over the coincidentally shared surname), the complicated process of getting the film off the ground, AC's determination to pare the dialogue down to a bare minimum, creating a sense of realism, fitting an image intensifier to the 16mm camera, getting the sound right, and a good deal more. He praises AC's collaborative approach, and tells a saddening story of how AC claimed that he'd finally worked out how to make a great Hollywood movie shortly before he was diagnosed with terminal cancer.

Alan Clarke: Out of His Own Light (Part 10) (12:34)

An interesting discussion on Clarke's use of walking shots and how they more fully involve us with the characters gives way to detailed coverage of the making of Contact, with lead actor Sean Chapman a fountain of fascinating memories of the shoot – "It's a film about the army, but it's not about the army," Clarke memorably told him.

|