|

DISC 4

| The Love-Girl and the Innocent (1973) (127:09) |

Slarek |

|

Alan Clarke returned to his theatrical roots for this ambitious adaptation of the 1969 play by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, which is set over the course of a week in a Soviet prison camp during the Stalin era. The Love-Girl of the title is the unhappy Lyuba, a pragmatic survivor who reluctantly trades sexual favours with those in positions of influence and power in order to secure better rations or more comfortable work details. The Innocent is Nemov, a reserved production chief whose position is usurped and who falls for Lyuba, but cannot bear the thought of sharing her with others.

Although the developing relationship between Nomov and Lyuba is central to the narrative, it actually occupies a surprisingly small percentage of the play’s running time and does not really kick off at all until a good way in. Indeed, the focus of the first half is more wide-reaching, providing a multi-stranded picture of life in the camp in which Nemov and Lyuba are not standout characters but part of a large and busy ensemble. And these are not hardened criminals but men and women serving 10-year sentences for convictions under what was known as Article 58, which was used to punish those whose words or deeds were deemed in any way contrary to the dictates of the state, men and women who are here are shown to be victims of custodial incompetence and self-interest.

Clarke was clearly not interested in compromise here. Where other directors might have scaled the play down and shot in the studio, Clarke chose to film at an ex-RAF camp in Norfolk using the BBC’s Outside Broadcast unit. This allowed him to use a multi-camera studio set-up in an actual location and it really pays off, giving the production a sense of almost cinematic scale by providing ready-made sets that would have been expensive and sometimes impractical to create in the studio. It also makes it possible to see a genuine skyline in daylight and the cold breath from mouths at night, and allows the foundry workers to carry out real smelting and casting.

The uniformly superb cast does include a couple of surprises for those new to the production. Consistently agitated taskmaster Gurvich is performed with typical authority by a pre-I, Claudius Patrick Stewart, and the quiet-spoken Nemov is played to perfection by a young David Leland, the very same David Leland who went on to write Beloved Enemy, Psy-Warriors and the searingly brilliant Made in Britain for Clarke. He’s matched at every step by Gabrielle Lloyd’s simultaneously resolute and vulnerable portrayal of Lyuba, whose battle to balance her desires with her survival instincts are written all over her face and body language. Appropriately, it is they who ultimately provide the play with its heart and make the final scenes so unexpectedly moving.

I’ll freely admit to not being familiar with Solzhenitsyn’s play before watching this version (although research suggests that any stage production would face some significant technical hurdles), but I was riveted by Clarke’s interpretation, despite occasionally struggling to remember who was who in this glum world of dark-walled rooms, cropped hair and tattered clothing (costume designer Reg Samuel and makeup artist Jean McMillan really do deserve a special mention here). It’s the longest work in this set by quite a stretch, but don’t let the subject matter or false preconceptions about Russian literature put you off – this is classic television drama of the highest order.

| Penda’s Fen (1974) |

Jerry Whyte |

|

| |

'It was a time when wise men/Were not silent, but stifled/By vast noise. They took refuge/In books that were not read//Two counsellors had the ear/Of the public. One cried 'Buy'/Day and night, and the other/More plausibly, 'sell your repose.'" |

| |

R.S. Thomas, Period |

| |

'The public have lost the imaginative strength they once had. Their sight and will to see what's really going on has been steadily weakened by the entertainment barons for gain and by the yes men for cravenness. We're not people anymore with eyes to see, we're blind gaping holes at the end of a production line, stuffing with trash." |

| |

Arne, Penda's Fen |

Admirers of Alan Clarke will have gasped in wide-eyed delight when they learnt of the BFI's plans to release the entire BBC back catalogue of that peerless original in an expansive, regrettably expensive 13-disc box set. A similarly sharp and widespread intake of breath no doubt greeted the equally welcome news that the release of Dissent and Disruption: Alan Clarke at the BBC (1969-1989) is being tied to a BFI Southbank retrospective on the 'Bresson of Birkenhead'. Here at Cineoutsider, excitement contended with trepidation at the daunting challenge of covering such a vast, varied and singular body of work, but our joy was unconfined when we heard of the BFI's judicious decision to grant Clarke's BBC drama Penda's Fen a stand-alone release. The reputation of this seldom screened masterpiece, a dazzling jewel in the Play for Today crown, has risen steadily, on a tide of reverential whispers, since its initial broadcast in 1974. It breaks to the surface now, free at last of the copyright chains that submerged it, to heartfelt cries of 'All power to the BFI' and, in certain quarters, muted mutterings of 'About-time-too'.

Colossally important though the BFI's Alan Clarke box set and film season are, the solitary release of this haunting masterpiece is an event of similarly monumental cultural significance, one that honours a holy trinity of maverick geniuses: director Alan Clarke, producer David Rose, and writer David Rudkin. Each brought his preternatural gifts to bear on this unique, unforgettable film; each deserves a statue on Trafalgar Square, if anyone does. It says much about a deep, disreputable strain of craven and myopic English conservatism that dynamic dissident voices such as Clarke and Rudkin have not been more widely heard and heeded. It speaks volumes of Rose that he displayed the courage of his convictions by giving them free rein while Head of the BBC's Regional Drama at Pebble Mill. Why the BBC didn't see fit to release the many Alan Clarke films in their archives themselves, they alone can say.

Penda's Fen is a breathtakingly complex, bravely ambitious, expertly executed and profoundly subversive Pilgrim's Progress in reverse. It charts the rebellious journey of a sanctimonious clergyman's son from doctrinaire adolescence to emotional, political and sexual maturity. At the start of his quest, young Stephen Franklin gazes dreamily across a sun-dappled green and pleasant land and, stirred by Edward Elgar's emblematic oratorio 'The Dream of Gerontius', asks himself how he might best serve his country. By journey's end, he no longer wishes to follow England's 'Aryan national family on its Christian path," is more relaxed about his homosexuality, and has shaken off parochial, parroted patriotism in favour of more heterodox and nuanced notions of nationhood earthed deep in the pre-Christian pagan past.

This mysterious, mystical and multi-layered film presents a persuasive challenge to the established order, provides an alternative vision of England, and simultaneously delineates the febrile turbulence of adolescence and sexual awakening with a boldness, precision and respect seen in few other films. David Rudkin's radical treatment of adolescence and politicisation is exemplary. He laid down markers for a path few others have followed. Willy Russell's 1983 TV drama One Summer walks that path with sure stride, Suffragettetraverses it, gingerly and tangentially, by showing how its central character, Maud, moves steadily from formative personal experience to a wider understanding of, firstly, herself, secondly, of politics, and, finally, of the need for direct action.This is David Rudkin's film as much as, if not more than Alan Clarke's: the originality of its conception, its architecture, and the quality of the writing make this primarily a scriptwriter’s success. Fiercely political without being glibly didactic, Ruskin fuses one bright, uptight public schoolboy's growing doubts and crumbling certainties with a state-of-the-nation assault on the shibboleths and platitudes of family, race, religion, school, state – the whole damned, dirty shooting match of 'straight' society. He deftly contrasts Stephen's passage to enlightened self-realisation with the groupthink of 'the herd of independent minds' – most notably in a scene in which his schoolmates and fellow cadets round on him as a pack for his refusal to conform.

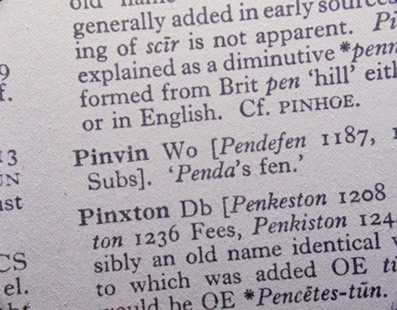

As Stephen's moral compass swivels and the tectonic plates of his universe shift, he comes to see himself, those in his orbit, even the landscape of his boyhood in a different light. His father proves to be more interesting than he'd allowed and other than he'd assumed. He develops affection and respect for the radical writer, Arne, and his wife – a progressive couple he formerly despised. Having initially viewed the Arnes' childless marriage as an example of divine justice, he comes to hope they can adopt: 'I hope they give you lot's of children, a whole tribe, because you're interesting people and your children will have interesting lives." The very names of places he thought he knew change before his eyes and take on fresh significance (Pinvin, Pinfin, Penfen, Penda's Fen). The countryside comes to seem less and less benign. Arne (a surrogate Ruskin as much as Stephen is) suggests that chilling state experiments are afoot beneath the land. And, as Stephen unravels before aligning with his authentic self, as his pubescent infatuations solidify into adult sexual desire, things become increasingly strange and dark, occasionally apocalyptic and violent.

At one point, Stephen awakes from feverish sleep to find the local milkman, Joel, perched upon him as a devilish apparition. Elgar and the pagan King Penda, too, materialize as visitations. He dreams of demons circulating around church steeples. He sees angels in fields. A starling is crushed beneath the wheels of a vehicle as Stephen looks on, paralysed and speechless. After a road accident, he stumbles upon a pagan ceremony in which children have their hands hacked off on a chopping block. Such visions may merely constitute the overspill of an overwrought imagination processing changes taking place in mind, body and soul, but they are real to Stephen. He takes his dreams for reality because he believes in the reality of his dreams. The fine line dividing perceived reality and the world of myth, symbol and spirit vanishes. All that is solid melts into air. The centre cannot hold.

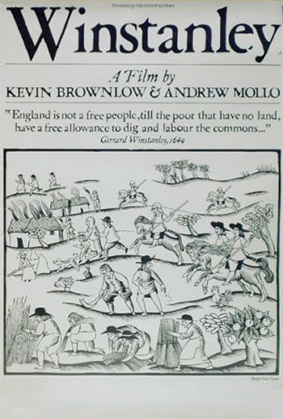

Both of its time and in advance of it, Penda's Fen is imbued with the spirit of questioning revolt that was 'in the air' in 1974, while prefiguring our modern respect for difference and diversity and presenting a retort to Heritage culture before the event. It was also a 'queer film' before the term was invented. In Rudkin's view “sexuality is the central vital essence of a human being, the most pre-political thing in us, which inevitably conflicts with the determinism and behaviourism of a genitally-organised society . . . the feminist complaint that men are not connected to their emotions facilely (fascistically?) discounts the gay man, who is ultimately anti-capitalist in his refusal to organize his sexuality in terms of reproduction." Steven recoils when a replica Mary Whitehouse and her husband, whom he once admired and defended as 'a mother and a father of England," seek to claim him for their cause. He tells the censorious couple: 'My race is mixed. My sex is mixed. I am woman and man, light with darkness, nothing pure. I am mud and flame." Astonishingly bold, one might think, for its day, but Rudkin mined a rich vein of revolt in a contemporary counter-culture from which he drew and to which he contributed. Penda's Fen offers an alternative cartography or choreography of landscape and history equally evident in films such as Michael Reeves' Witchfinder General (1968), Derek Jarman's A Journey to Avebury (1971), Robin Hardy's The Wicker Man (1973), Kevin Brownlow & Andrew Mollo's Winstanley (1974), and David Gladwell's Requiem for a Village (1976).

For all its philosophical and theological depth; for all its knowing and welcome references to pagan myth, the Greek classics, and classical music; Penda's Fen is an explicitly political work – in that broadest and truest sense of the political which encompasses all of human experience and insists on subjecting it to democratic control and scrutiny. This is an adult film that addresses an audience of intelligent citizens and informed spectators capable of free thought. It works on the assumption that people think and feel deeply, read enlightening books and watch challenging films, question their society and their own circumstances – even or especially adolescents. That the film was broadcast on TV and seen by millions when television had only three channels calls the modern obsession with viewing figures and advertising revenue into question. We’ll return to that question below.

If the film owes a clear debt to Lindsay Anderson's If.... (1968), it does so, too, to certain seminal books of that era; particularly Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, (1962), E.P. Thomas's The Making of the English Working Class (1963), Christopher Hill's The World Turned Upside Down (1972), and Raymond Williams' The Country and the City (1973). Ideas leap from book to book, book to film, film to film. This process of cross-fertilisation is part of the rich soil from which the above-mentioned films and Penda's Fen grew. The radical ideas and movements recuperated and celebrated by Hill and Thompson percolated into the wider culture. From there they filtered into Penda's Fen, Witchfinder General, Winstanley, and Caryl Churchill's 1976 play Light Shining in Buckinghamshire – all of which, in their turn, recycled and circulated the idea that 'the earth is a common treasury for all'.

In his A People's History of England, A. L. Morton argues that the Levellers - the Left within the New Model Army (itself the Left of the country, 'the common people in uniform') – were “ahead of their times" in their desire for a democratic Republic. "The role of the Levellers," he says, like that of the Jacobins in the French Revolution, “was to carry the movement to positions which could not be permanently held but whose temporary seizure safeguarded the main advance." Penda's Fen performs the same function within television and film culture. It contrasts the countryside (in this instance, the low-lying arable land in the shadow of the Malvern Hills) with the city (here, nearby Birmingham).

In so doing, it offered a radical reading of the land and the past at odds, though tinged by, entrenched pastoral ideas of the country as site of backwardness. As Raymond Williams notes in The Country and the City: 'On the country has gathered the idea of a natural way of life: of peace, innocence, and simple virtue. On the city has gathered the idea of an achieved centre: of learning, communication, light. Powerful hostile associations have also developed: on the city as place of noise, worldliness and ambition; on the country as a place of backwardness, ignorance, limitation."

While the influences of Carson, Hill, and Thompson seep into the film by osmosis, that of Williams is writ large in its every frame. He is present when the Rector says to Stephen: 'The village is sneered at as something petty, petty it can be, yet it works. The scale is human, people can relate there, and may yet, in the nick of time, revolt and save themselves." Which is to say, the village has a centre, unlike the city. To paraphrase academic Jim Berlin, the city has no centre – only shopping centres, financial centres and industrial centres, none of which are the centre of anything but themselves. Williams is there, again, when Arne addresses a public meeting and defends industrial democracy against the idea that trade unions are 'holding the country to ransom." He asks: 'Is it strikers who play monopoly for real with our countryside and cities? Is it strikers who smash the fabric of our communities for greed? Is it strikers who throw up into the air million upon million on bungles, deliriums and fantasies? Is it strikers who pillage our earth, ransack it, drain it dry for quick gain, to hand on nothing but dust to the children of tomorrow?"

Rudkin cuts through the dichotomy positioning the country as site of stability and the city as the site of revolt. But his complex view of the rural past in Penda's Fen is tinged with resilient, soporific pastoral myths – perhaps inevitably so, given that he taught up in rural Worcestershire and that those myths are so pervasive. Williams again: 'So much of the past of the country, its feelings and its literature, was involved with rural experience, and so many of its ideas of how to live well, from the style of the country-house to the simplicity of the cottage, persisted and were even strengthened, that there is almost an inverse proportion . . . between the relative importance of the working rural economy and the cultural importance of rural ideas." Rural labour is absent from Rudkin's picture of the land. We meet a milkman, a postmistress, a writer, and a preacher, but no farmers or shepherds. A few sheep graze in the fields, but nobody seems to tend them. Rudkin fetishizes the pretty parsonage and the 'good life' lived by Arne and his wife, even as he insinuates uncertainty, particularly through Arne's anti-establishment village hall speech about underground nuclear bunkers or command centres. Arne says: 'Poets have hymned the spirit of this landscape, our greatest composer enshrined it, farmland and pasture now – an ancient fen. The earth beneath your feet feels solid there. It is not! Somewhere there, the land is hollow."The language is as rich as the ideas.

The view of England Rudkin presents in Penda's Fen is more selective than that offered by Orwell in his selectively quoted phrase: “The clatter of clogs in the Lancashire mill towns, the to-and-fro of the lorries on the Great North Road, the queues outside the Labour Exchanges, the rattle of pin-tables in the Soho pubs, the old maids biking to Holy Communion through the mists of the autumn mornings – all these are fragments, but characteristic fragments, of the English scene." But, for all that, the tension in the film between its absorption of pastoral myth and resistance to it places in opposition to Heritage culture, which as Patrick Wright has said, presents an elitist past 'purged of political tension" – a stylized, nostalgic, reactionary, retrograde, ruling class version of England and her past.

Penda's Fen stands at the crossroads of competing versions of Englishness and points toward an ancient landscape containing traces not only of pagan kings and dead composers but of rick-burners and machine-breakers, Land Chartists and Levellers, Ranters and Shakers, Diggers and Lollards. The film positions the English landscape as a site of conflict, contest and control. The radical ideas of suppressed and nominally 'unsuccessful' movements often lie dormant beneath the social soil until the rain of change force them toward the light again. Zola's Germinal concluded with a radically optimistic reference to such possibilities: “Men were springing up; a black avenging host was slowly germinating in the furrow, thrusting upwards for the harvests of future ages. And very soon their germination would crack the earth asunder." The ancient animosities of dead, defeated generations stare defiantly and contemptuously back at Stephen through the eyes of a local worker amending the spelling of Pinvin on a road block sign. One suspects Stephen will come to understand that steely glance as he claims his true inheritance.

Penda's Fen is most definitely not a film about the past alone; it is about its present and our future too. Rudkin remained attuned to current political events while involved in his archeological excavation of aspects of England's past. The film was written and filmed during a period of working-class industrial militancy, against the backdrop of the three-day week and a national NUM strike. Other political realities fed into the film. Rudkin was of mixed English-Irish protestant parentage and his 1973 radio play on the gay Irish rebel Roger Casement, Cries from Casement as His Bones are Brought to Dublin, continued his subversive exploration of the ways the human personality is shaped by one's origins and ethnicity, political and moral convictions, psychology and sexuality. Ireland was a 'hot issue' in the early 70s. Events such as Bloody Sunday, the re-imposition of internment, and the imposition of the Diplock Courts intensified the Irish Republican struggle and spread a destabilising sense of unease and uncertainty as surely as the three-day-week and trade union militancy. English racism, too, was front page news in 1974, with Enoch Powell's 'rivers of blood' speech' and the rise of the National Front adding to a growing sense of a country on the verge of collapse. The international recession that accelerated Britain's decline as a global economic power was accompanied by the intensification of globalization and entrenchment of the power of multinational corporations. All this, as Andrew Higson says, “disturbed traditional notions of national identity," notions further threatened by 'the empire coming home', in the form of multiculturalism, and 'the chickens coming home to roost', in the form of rising levels of unemployment, an increasing assertiveness within local nationalisms, and growing political revolt. These troubling realities infused the film and intensified its atmosphere of apprehension.

While contemporary politics find their way into the film, one of the more seemingly surprising aspects of this endlessly surprising film is the way it sidesteps popular culture. Stephen prefers Elgar to T. Rex and his shelves are lined with Greek and Latin classics – with Aeschlyus and Cicero, Euripides and Livy, Heroditus and Tacitus. This ceases to be surprising when one learns that Rudkin was a Classics scholar, taught Latin and Music at second school level, and has translated both Aeschylus and Euripides. Described by the Observer as “Britiain's greatest dramatic poet," Rudkin is the archetypal polymath: a linguist, librettist, translator, teacher, and writer for radio, stage, television and cinema. His ardent cinephile predilections are evident not only in his 1993 radio play The Lovesong of Alfred J. Hitchcock, the monogram on Carl Dreyer's Vampyr(1932) he produced for the BFI Classics series, and his work with François Truffaut on Fahrenheit 451 (1966), but also in the extended meditation on Joan of Arc that punctuates Penda's Fen and in the acknowledged debt the film owes to British Romanticism of Hammer horror films.

Despite his concern with, and insight into English culture, Rudkin claims affinity to R.S. Thomas and Wales. There is certainly something of Thomas's insistence on the importance of place and past that chimes, but he is probably closer to Iain Sinclair, another Welsh writer. Sinclair describes himself as a Welshman disguised as a Londoner and Rudkin often strikes one as a Londoner disguised as a Celt. Like Sinclair, he quarries hidden histories and charts occult-psychogeographic fault lines. I once hosted an event with Sinclair during which an arch-rationalist in the audience asked him whether he actually believed in dowsing and druids and ley lines or just saw them as metaphors. Sinclair said he believed in them as metaphors. One can imagine Rudkin saying something similar. He certainly shares both Sinclair's belief in things beyond the reach of rational thought and his heretical, sceptical attitude to authority. Although Rudkin stands opposed to that version of Imperial nationalism implied by Auden's image of Newton's 'apple, falling toward England', he might applaud (as R.S. Thomas did) T.S. Eliot's line 'History is now and England' – because it merges eons, links time to place, and, paradoxically, suggests that place could be here, there, or anywhere.

Rudkin says, "things came together" on Penda's Fen. They certainly did, and how. How could they fail to when a troika such as Alan Clarke, David Rose and Rudkin was involved. The emphasis of this review has been on David Ruskin, because his writing lifts the work to levels attained only by a handful of other TV films, but also because my colleagues here will press on to cover the career of Alan Clarke. It must be noted, though, that the film succeeds as spectacularly as it does partly due to Clarke's consummate direction and his perfect casting decisions. The entire cast is flawless but Spencer Banks as Stephen, Ian Hogg as Arne, and John Atikinson as Reverend Franklin do the lion's share of the work and so must reap most praise. To a generation grown used to accelerated, assaultive images, the pacing of the film will seem slow, perhaps clumsy; those familiar with Bresson and Dreyer will appreciate Clarke's skill at allowing images and ideas to breathe and understand that his purpose was to build a steadily rising, unhurried and organic whole.

Mention must also be made of David Rose. I pause to dip my flag in salute of that courageous, pioneering producer, without whom this extraordinary film may never have been made. It was he who brought Alan Clarke and David Rudkin together. No less inclined to risk than Clarke and Rudkin, Rose saw no separation between films for television and cinema. He helped create the BBC's Play for Today series, perhaps British television’s finest hour, and, as if that were not enough, he also helped revitalize the British film industry in the 80s while Commissioning Editor of the fledgling Channel Four - producing an incredible 136 films. We can thank him, among other things, for such imperishable classics as Nuts in May (1976), Licking Hitler, (1978), Boys from The Blackstuff, (1980-82), A Very British Coup (1982), Comrades (1986), Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), The Last of England (1988), and, of course, Penda's Fen. At the BBC's Television Centre and, later, at the Pebble Mill studios, he nurtured the likes of Alan Plater, Andrea Dunbar, David Hare, Mike Leigh, Ken Loach, and Willy Russell. At Channel Four, he supported the likes of Terence Davis, Bill Douglas, Stephen Frears, Peter Greenway, Derek Jarman and Mike Newell. Rose took risks because he trusted his audiences. He trusted his writers and directors too, and they rewarded him with remarkable works that challenged the national narrative. In 1987, David Rose received a Special Prize at Cannes for services to cinema; in 1997, he received a BAFTA Fellowship, and, in 2010, he received a BFI Fellowship.

But for Clarke, Rose and Rudkin, I might argue that Penda Fen's elevated television to the heights of cinema at a time cinema was stooping to the levels of television. But for them I would snort in derision at the widely held belief that it is on television, not in cinema that we are most likely to find innovative, edgy work. Such are their towering achievements, and such is the significance of Penda's Fen, that it seems fitting to close with a few thoughts about the way television has affected the transmission and reception of images since 1974. This site is primarily devoted to the cinematic so a concluding, if not conclusive sideswipe at television doesn't seem out of place and is, anyway, irresistible. Even at the time of its creation, Penda's Fen represented a counter-television tendency that contributed to, and arose from within a wider challenge to the dominant culture and the status quo. The film's reputation has grown, albeit beneath the radar until now, in direct proportion to the inexorable rise of the kind of vacuous TV it challenged, and which cinema was powerless to arrest. It was special even in an era of more daring programming and has come to seem even more so now.

The flow of images has increased exponentially since 1974 but of course television's usurpation of cinema's privileged position in popular culture predated Penda's Fen. In an acidic New Yorker article on the state of cinema in 1980, Pauline Kael reminded her readers that people often go to the cinema regardless of the film and that what happens in front of the silver screen is as important as what happens on it. She said: “The movies have become so rank in the last couple of years that when I see people lining up to buy tickets I sometimes think the movies aren't drawing an audience – they're inheriting an audience." While blaming Hollywood's malaise primarily on the philistine avarice of risk-averse studio executives, Kael also targeted television: “ . . . audiences have been so corrupted by television and have become so jaded that all they want are noisy thrills and dumb jokes and images that move along in an undemanding way, so they can sit and react at the simplest motor level."

Italian academic Gabrielle Pedullà discusses such 'motor level' responses to images in his book In Broad Daylight, a historic survey of audiences, the auditorium, and the impact of television aesthetics on viewing patterns. Pedullà contrasts the auditorium's culture of “maximum constraint, maximum concentration” with the "extreme volatility" of Serge Daney's home-based 'zapper'. This new viewer has been empowered and liberated by the remote control but remains subject to 'the aesthetics of the shark' – an allusion to scientific research, conducted in the 1960s, in which the male subject's pupil automatically dilated when viewing images of sharks and naked women, while the female subject's responded identically to images of babies and naked men. Television content, Pedullà says, chained as it is to audience ratings second by second, reflects those findings. Who can dispute it? Who doesn't occasionally turn on to drop out occasionally, slump onto a sofa in search of distraction, enlightenment or surprise, only to be disappointed day in, day out. Zap-nah, zap-nah, zap-nah, ad infinitum.

Reviewing Pedullà's book online, critic Wheeler Winston Dixon offers an interesting assessment of the way television and individual media content has evolved. He notes that shot structure and framing were altered by a centering imperative designed to accommodate TV and the Web, but is actually more concerned about the dumbing down of cinematic content to accommodate increasing numbers of multiplexes – “to create the loudest, emptiest, most assaultive movies the medium has ever seen, a non-stop world of CGI fantasy with the imaginative depth of a demented adolescent." Dixon grants the last word to a sage friend of his, who says: 'You see on TV and DVD you can inspect a film. But you can't experience it." Which brings us back to Penda's Fen. Dixon's friend has a point, but many of those who saw Clarke and Rudkin's film when it was first broadcast on the BBC in 1974 or when it was repeated on Channel Four in 1990 would disagree. Watching Penda's Fen for the first time is a changing, moving and haunting experience. I confess, I forget when I first it, but I do remember being baffled and excited by it. I yearned to watch it again, immediately and often. A few years ago, I dragged a reluctant friend (with whom I share a penchant for Willy Russell's One Summer) to see it at the Roxy on Borough High Street, during a Scala Forever festival screening. It became, and remains his favourite film. The BFI have earned the undying gratitude both of those us who already revere this unique, passionate, magnificent film and can now delight in repeated home viewings and those even luckier ones who can inspect and experience it for the first time. How I envy them.

The Love-Girl and the Innocent was shot on analogue video on outside broadcast cameras and boasts a strong level of detail and well balanced contast, no mean feat for a work with whole scenes set largely at night or in interior gloom. The black levels can soften a tad when the light levels drop, but the detail is still there and there are no other issues. The soundtrack has been very well mixed and is in fine shape – even the softly spoken dialogue is clearly audible, and there is no distortion when the characters shout.

Remastered and restored, we can presume, from the original 16mm film negative, Penda's Fen looks better here than it likely ever has outside of a BBC preview screening room. Boasting crisp detail, perfectly pitched contrast (blacks are solid, shadow detail is good and there are no burn-outs on highlights) and sumptuous colour, with the sunsets in particular gorgeously rendered. A fine level of film grain is visible and there is hardly a dust spot or mark to be seen anywhere here. A lovely transfer of a visually sumptuous film. The mono soundtrack is clear and free of hiss, fluff or any other sundry damage. The inevitable treble bias is most evident in the music, but otherwise the sound is in excellent shape.

Alan Clarke: Out of His Own Light (Part 4) (18:37)

The Love Girl and the Innocent gets brief but still interesting coverage here, as David Leland explains how he landed the lead role and set builder Mike Hagen recalls finding the foundry, bringing the fire brigade in to fire hoses into the air to simulate rain, and Clarke shooting the production like a film but with multiple cameras. The majority of the running time is given over to exploring the writing and production of Penda’s Fen, built primarily around a revealing interview with its celebrated writer, David Rudkin, with contributions from actor Sean Chapman, film reviewer Harold Schumann, and Davids Hare, Leland, Rose and Yallop.

|