|

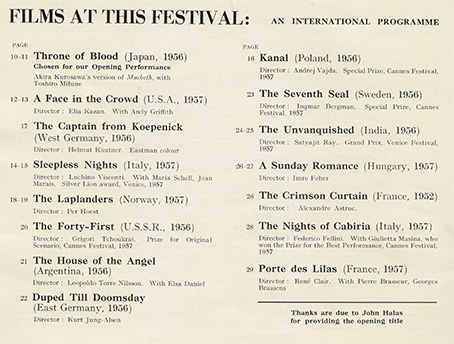

When the London Film Festival was launched, in 1957, it described itself as the 'festival of festivals'. That ambitious designation masked the relatively modest scale of its trailblazing achievement. Back then, the likes of Richard Roud selected fifteen films from the pre-existent festivals of Berlin, Cannes, Edinburgh and Venice, which now seems like child's play compared with the vast logistical exercise of trawling the world's five hundred-odd festivals to bring home 'the best of the rest'. For this year's festival, the British Film Institute's team of programmers and advisers viewed over 4,500 films before arriving at their final selection of 240 features and 182 shorts. A glance at the inaugural festival programme (courtesy of the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum) reveals shocking absences as well as startling quality: there are films by Bergman, Fellini, Kurosawa, Satyajit Ray, Visconti and Wadja – but nothing at all from Africa, Asia or the Arab world, and no single film made by a woman.

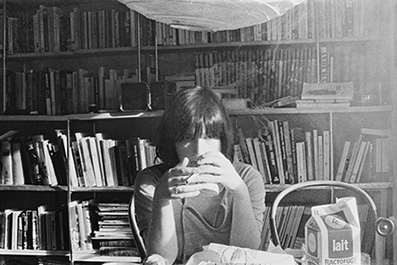

In her annual LFF brochure address, Festival Director Claire Stewart says: "The LFF programme team declares 2015 the year of the strong woman." At this point, we pause to dip our flag in honour of legendary Belgian-born film-maker Chantal Akerman, who died in Paris on Monday, aged 65. Drawn to cinema by a formative teenage encounter with Godard's Pierrot Le Fou (1965), she will probably be best remembered for her groundbreaking magnus opus Jeanne Deilman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). Her lasting legacy, though, lies in dozens of films that reflected her restless radicalism, ceaseless invention and fearless iconoclasm. "Whenever I say anything," she once said, "I want to say the opposite as well." In his New York Times obituary, J. Hoberman described Chantal Akerman as "one of the great film artists of her generation . . . one of a handful of women whose films and example changed the course of cinema history." The ICA's long-running season – billed as "the most complete retrospective ever attempted of Chantal Akerman's entire cinematic oeuvre" and organised by the collective A Nos Amours – was due to end on 30 October with a screening of her final film, No Home Movie (2015), a materclass and Q&A. That film was already scheduled for screening at the New York Film Festival, which last night marked her passing with a free double bill screening of Jeanne Deilman and her self-portrait Chantal Akerman by Chantal Akerman (1997). It is a crying shame the LFF found no room for No Home Movie in this year's programme and it would be wonderful if plans were afoot to honour her in similar fashion before the festival closes.

This year's festival certainly got off to a flying start. Sarah Gavron's Suffragette, Davis Guggenheim's He Named Me Malala and Jay Roach's Trumbo were among those films reminding us, as Franz Fanon once did, that freedom doesn't fall into our hands like an apple from a tree but is, rather, "a precious reward, the shining trophy of struggle and sacrifice." The Opening Night Gala screening of Gavron's film on Leicester Square was a famously colourful occasion. As the harsh white glare of flash photography announced the arrival of lead actors Helen Bonham Carter, Anne-Marie Duff and Carey Mulligan, Sisters Uncut feminist activists detonated green and purple smoke bombs, before storming the red carpet to protest austerity cuts and domestic violence. It did the heart good and lent unexpected meaning to the 'experiential' organising themes of Dare, Debate, Thrill, Laugh and Love introduced into the festival under Claire Stewart's stewardship.

That disruptive action demonstrated the contemporary relevance of Suffragette. By bursting into the media bubble of the festival to assert that feminism's job was not yet done, the sisters placed the politics of the wider world at its very heart. Meanwhile, across town at BFI Southbank, smaller audiences were settling down to watch double bills on two indefatigable directors who challenged Chinese and African variants of tyranny respectively. In NFT1, Jai Zhangke's latest feature, Mountains May Depart, was twinned with Walter Salle's documentary Jai Zhangke, A Guy from Fenyang. Simultaneously, audiences in NFT3 were savouring first Ousmane Sembène's landmark films Boram Sarret (1963) and Black Girl (1966) then the biopic Sembène! Samba Gadjigo and Jason Silverman's documentary charts the life of the Senegalese dockworker and fisherman turned novelist and director who all but invented African cinema and whose films made an incalculable contribution to the liberation of African women, particularly by challenging the barbaric practise of female genital mutilation.

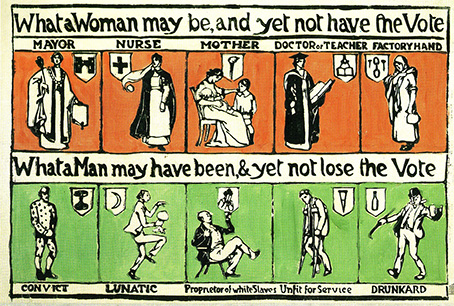

Shortly after watching Sarah Gavron's inspirational film, my eye was drawn to two magazines in a railway station newsagent. Meryl Streep appears on the cover of Women & Home while Carey Mulligan graces the 'The 'Feminist Issue' of Elle. A 'trending' post by TEAM ELLE, tells readers why Suffragette is "the most important film this year, maybe ever . . . " Even setting aside the questions raised by the way the film has been marketed, the minimum that must be said here is that there's something disconcerting in such glossy manifestations of shallow 'go-girl' solidarity and the breathless excitement of such reactions to the film; just partly because the former is so obviously at odds with the suffragette battle cry of 'Deeds, not words' while the later betrays a troubling ignorance about both cinema and, more worryingly the women who secured the hard-fought-for rights all too often taken for granted. The suffrage struggle was not immune to the divisions that bedevil all movements for radical change and the feminist activists of Sister Uncut, perhaps inadvertently, highlighted the recrudescence of ancient arguments about strategy [It's worth noting at the outset that the 'suffragettes' of the Women's Political and Social Union (the WPSU) were condescendingly labelled as such by the Daily Mail to differentiate them from less militant, constitutionalist 'suffragists' such as Millicent Fawcett's National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).].

I found myself wondering what the 'second wave' feminists associated with Spare Rib would say about Woman & Home, and what Chantal Akerman would've made of it all. It had me reaching for Naomi Klein's The Beauty Myth and Christopher Hitchens' Letters to a Young Contrarian. Speaking about his friend Dr. Israel Shahek, Hitchens says: "Nothing in his life, as a Jewish youth in pre-1940 Poland and subsequent survivor of indescribable privations and losses, might be expected to have conditioned him to welcome the disruptive. Yet on some occasions when I have asked him for his impression of events, he has calmly and deliberately replied: 'There are some encouraging signs of polarisation'. Nothing flippant inheres in this remark; a long and risky life has persuaded him that only an open conflict of ideas and principles can produce any clarity. Conflict may be painful, but the painless solution does not exist in any case and the pursuit of it leads to the painful outcome of mindlessness and pointlessness; the apotheosis of the ostrich."

Hitchens inadvertently maligned ostriches; that extraordinary bird does not, actually, bury its head in the sand as is widely assumed. Many humans do though and it's to be hoped that this year's festival has already ruffled a few feathers and startled a few out of sandy complacency. Sarah Gavron's deeply moving film Suffragette will doubtless have done so as it focuses on the insurrectionary phase of the struggle for women's suffrage, on the lives of two working-class feminist militants, Maud Watts (Carey Mulligan) and Violet Miller (Anne-Marie Duff), and on the State's reactionary use of dirty tricks, intimidation, violence and covert surveillance techniques. If the script is a little heavy-handed and the direction is a tad too conventional to contain the radicalism of its content, this is a stirring, heartwarming, urgent film nonetheless.

Maud and Violet work at the Glasshouse Laundry in Bethnal Green, where their lives are made miserable by atrocious pay and conditions and by their odious boss Mr Taylor (Geoff Bell), an alehouse bigot and sexual predator. The film single-handedly fills Claire Stewart's quota of strong women while doing a magnificent job of showing how much more testing the political activism of working-class women was in comparison with that of upper-class women and how much greater their sacrifice. Maud is drawn into the suffrage struggle with the WSPU when she accompanies Violet to the House of Commons to hear her testify on working conditions. Violet cannot speak as she has been subjected to sickening domestic violence (of a kind that, as Sisters Uncut pointed out on Wednesday, still claims the lives of two women per week), so Maud reluctantly takes her place. There are echoes of Made in Dagenham in the way Carey Mulligan's Maud, like Sally Hawkin' Rita O'Grady, falteringly finds her voice when interrogated by the powerful; echoes too in the spineless ways both Maud's husband, Sonny, and Rita's husband, Eddie, react to their more radical better halves' growing self-confidence and strength. At one point, Maud says, defiantly: "We're half the human race. You can't stop us all." The conservative reaction of embattled masculinity to women's militancy is a subtext of both films.

Carey Mulligan portrays Maud's pain as a mother torn between her competing commitments to her son and her new found political convictions with understated and captivating sensitivity. On the down side, Mulligan fails to replicate either the steely grit she displayed in Steve McQueen's Shame (co-written with Suffragette's scriptwriter Abi Morgan) or replicate the spontaneous anger that would have arisen from deep within Maud (for example, in a scene of retributive violence in the workplace). Anne-Marie Duff is flawless as battle-wearied Violet, Ben Whishaw makes most of the limited material he's given to work with as Sonny, Brendan Glesson is commanding as the Irish servant of the secret state who's seen it all before, but Helen Bonham Carter (great-granddaughter of Liberal Prime Minster Herbert Asquith, a fierce opponent of women's suffragettes) steals the show with an extraordinarily nuanced and powerful performance as chemist-cum-bomb-maker Edith Ellyn. Bonham Carter's name is so closely associated with Heritage cinema that her appearance on the cast list was cause for concern prior to seeing the film. Mercifully Suffragette avoids two traps that might easily have ensnared it without a less intelligent treatment: the damaging tendency to view the suffragettes as a Pankhurst family personality cult and, by and large, that of Heritage to prettify the past and purge it of bothersome political tension.

Although Meryl Streep is wheeled on for a brief appearance as Emmeline Pankhurst, the film's focus is resolutely on the women who formed the backbone of the suffrage movement and, although it displays the perfect pointillist detailing we've come to expect from cosy period drama, it represents working-class women with a rare respect reminiscent of Channel Four TV series The Mill. Over two series loosely covering the period 1830-1844, director James Hawes charts a period of growing organise revolt against injustice by focusing on Esther Price (Karrie Hayes), a real-life Liverpudlian mill worker whose testimony was used by those campaigning for the Ten Hour Bill to reduce child labour. Like Gavron's fictional Watts, Hawes' Esther observes and experiences sexual harassment in the workplace; like Maud, she carries within herself a sense of grievance that grows naturally into a defiant hunger for change, like Esther, she finds herself while bearing witness to injustice.

The differences between the TV series and film, though, are as revealing as their similarities. The Mill was grounded in forensic archive research into working-class social and political life in Quarry Bank Mill, Cheshire; Suffragette both honours and elides it. Abi Morgan clearly did considerable research too. In The Pankhursts: The History of One Radical Family, Martin Pugh records Christabel Pankhurst's quick-witted put-down of a heckler during the 1908 'Rush the House of Commons' handbill trial (at which the WSPU successfully subpoenaed Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George and former Home Secretary Herbert Gladstone as witnesses). At the trial the heckler shouted: "Wouldn't yer like to be a man, Miss?" Christabel replied: "Yes, wouldn't you like to be a man?" Morgan repeats that exchange verbatim in the film. Unfortunately, if she did any research into wider political agitation of the period covered by the film, it is not evident in the script.

Of course this is a film about the suffragettes and an inspiring tribute not only to their courage (not least while imprisoned and on hunger strike) and their sacrifice (not least that of Emily Wilding Davidson, who died four days after being flattened by the King's horse at the Epsom Derby). But even if one accepts the argument that history must be painted with broad brush strokes in narrative cinema, Suffragette might well have reflected the wider realities of the day, if only in workplace conversations. The period considered was marked not only by the great push for women's suffrage but by 'the great unrest', a period when trade union membership rose from 2.5 million to over 4 million, strike action and civil disobedience was a marked feature of industrial relations, and socialism was on everyone's lips. No workplace in the land, certainly not a laundry in Bethnal Green, would have been unaffected the mood of militancy within working-class communities. The war that was about to engulf the world and temporarily stop the suffrage movement in its tracks is also absent from the film. Despite or perhaps because of these elisions, Suffragette will surely inspire many thousands to explore a chapter of our radical history so shamefully buried for so long.

|