|

DISC 5

| A Follower for Emily (1974) |

Slarek |

|

Watching all of the Alan Clarke films in this set over a relatively short space of time, certain themes and motifs do tend to emerge. It seems clear, for example, that Clarke was fascinated by institutionalised micro-communities – the psychiatric ward in Funny Farm, the borstal in Scum, the military academy in Sovereign's Company are all good examples. It's a similar story with the 1974 A Follower for Emily, which is set almost exclusively in or just outside of a retirement home.

Essentially a sympathetic portrait of life within a home whose residents appear to be largely happy with their lot and whose staff are kindly and patient towards their charges, the narrative obliquely suggested by the title emerges in a deftly low-key manner, as the friendship between residents Harry and Emily develops to the point where they decide they should marry. It's an arrangement that ultimately fails to live up to Emily's hopes and expectations, as their Margate honeymoon is cut short by Harry's cheerless pining for home, and the attention and companionship she clearly expected the union would provide is not forthcoming.

Written by Brian Clarke, whose first work for television was the celebrated right-to-die play Whose Life Is It Anyway? (later made into a feature film by John Badham with Richard Dreyfuss in the lead role), A Follower For Emily was shot in a real retirement home, and although performed and scripted in a manner that identifies it as drama, it still oozes realism at every turn. A drama that is devoid of dramatic scenes, it unfolds instead as an observational piece peppered with engaging exchanges and acutely observed moments. It's also rare and refreshing, even 40 years after it was first transmitted, to see a film of any description with a cast of elderly characters who are not mocked, parodied or played purely for comedy value, but instead treated with the respect and dignity they deserve.

| |

"Clarke, Minton and I were in the King's Head. There was a rock group and they were doing this twelve-bar rock, and we had taken up a chant of this particular line, 'Why fucking not?' which seemed to capture the imagination of everybody in the pub. And when I left they'd been singing it continuously for about twenty minutes. Well, apparently, subsequent to my departure, a chartered accountant joined the throng, he was vaguely known to us. And pretty soon after that he, Clarke and Minton took their clothes off, and they were jumping up and down on the stage stark naked, chanting, 'Why fucking not?'" |

| |

Writer, David Yallop |

| |

"In the middle of Diane, Alan was arrested. One morning I went in and the PA said, 'Alan's not able to be here this morning.' I think because I was playing a fourteen-year-old they felt they shouldn't tell me why. But he was in court for having been rowdy in the King's Head and taking his clothes off." |

| |

Lead Actress, Janine Luvitski |

What a unique pleasure it is watching a film starring an actress whose work you are familiar with and being shown a side of her that shocks in a good way and also saddens you thinking of how much potential was squandered on work that never pushed her professionally ever after. You'll recognise the face instantly. Before she changed her name, Janine Drzewicki (pronounced 'Duvitski', the name she then adopted) was a young actress having just left theatre school with a handful of small credits on her CV. She had no agent so paid to have a photo of herself printed in Spotlight, the actor's casting resource which in those days occupied most producer's shelves groaning under their weight. From this photo alone, Clarke saw something and auditioned the twenty-three year old for the part of schoolgirl in the second year of her teens. There's no doubt in my mind that Clarke's instincts were so spot on, it's almost painful to watch. Duvitski is a revelation, being on screen in almost every scene. She manages to reveal an inner, turbulent emotional life that is at sharp variance to her outer shell of indifference and capability. It's telling that she seems to show the most tenderness to the man responsible for the crime done to her, one of the worst in society's long roster of horrors, a father's rape of his daughter. To be fair, there is never any suggestion to confirm the liaison was not consenting but we are talking about a fourteen year old girl so I know which way most sympathies would lay.

Duvitski has a very distinctive look (she came from an English mother and a Polish father) and while I instantly recognized her from work in One Foot in the Grave, About A Boy and This is Jinsy, there is no doubt she had shed loads of ability and a raw natural talent from the very start of her career. She's been fêted on stage as well as screen for a multitude of roles and should be a lot more celebrated than she currently is. She has started a lineage of acting talent; her daughter Ruby Bentall is her spit in looks and that distinctive voice as Minnie in Lark Rise to Candleford. There's a sense of the camera intruding on her (as if she was a reality star and no greater compliment can a pay an actor, total immersion and believability). Clarke's penchant for long takes suits her as she seems so at home in front of the lens, it's easy to accept there is no lens there.

Everything starts well enough. Here's a strong-willed young schoolgirl, seemingly a loner, whom the boys tolerate during football practices and fag breaks. Jimmy (Paul Copely) is very keen on her and as he lays his coat down for them both to sit on, I flashed on the utter terror of awkwardness that exists between a young boy and girl both of whom are expecting the other to make some sort of move. Bless her literal cotton socks as Diane just says "Do you want to give us a kiss?" Oh, didn't we all wish for such directness from our teenage friends? Before the brief snog, Jimmy talks about how the glass and rubble debris once covered by the grass of the pitch sometimes force their way through the soil causing havoc with the players. As a metaphor for the horrors that surface while we try hard to suppress them, it's a bit heavy handed but in the case of Diane herself, it's woefully true. A kind and considerate boy, Jimmy is keen for Diane to know he doesn't want to take physical advantage of her. There are two problems with this attitude however laudable; some girls want the boys to make the move just as curious and terrified about sex as anyone else and secondly and more disturbingly, at the age of fourteen, someone had already taken sexual advantage of her. As a viewer you have a vague idea in mind at what Clarke's simple direction and Diane's powerful performance is hinting but it's only when Diane hides a small newborn shaped parcel under newspapers in an industrial rubbish bin does the full horror strike home. It was Diane's son or daughter. It was Diane's sister or brother. We're in Chinatown territory here. The father is her own father…

Jimmy is gallant enough to propose despite the pregnancy. Once the secret is out, Diane is taken into care and given over to a priest, another 70s stalwart, Tim Preece (or the insufferable Tom from The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin). She will be cared for in a home while her father is imprisoned. Diane is keen to confess that she would never have hurt the baby… "He never guessed, not even Dad," she says. "Wasn't breathing when it came out, didn't make a sound, never moved…" Strong enough to weather this god-awful emotional and physical storm, Diane starts to bloom. Out of state care she gets a job in a garage where Harry, a local driver, flirts with her and takes her out but this time with an agenda less pure than Jimmy's. Her home life is tempestuous sharing with a warring couple with baby and a man whose regard for her is higher than most. It's when the shadow of the past catches up with her in the shape of her released father do things get complex. Diane still cares for this man and is given the choice to banish him for good. In reply, her father guilt trips her with the words "Would have done for myself if you said 'Go away'," and Diane's response gives you some hope…

Diane is a remarkable film about a subject that doesn't get covered much in the media. It's such a complex subject and not so easily brushed off with the idea that some men are monsters (though that is certainly the case more often than not). Diane is fourteen at the time of her impregnation – that's enough to claim 'rape'. But we see nothing of the abuse but cannot be sure exactly what role Diane played. The fact she doesn't shun her father after the event is telling but Clarke and writer David Agnew (more on him in a second or two) let the viewer chose where their sympathies should lie. David Agnew, in some ways is the opposite of cinema's Alan Smithee. It's the pseudonym trotted out by the BBC when the original writer is concerned enough by changes to his/her screenplay that they want to remove their name. Jonathan Hales, literary manager of the Royal Court in 1975 wasn't keen on Clarke's changes to his original two part script which was skewed much more towards the religious side of the story. The difference between Agnew and Smithee is that those who added to and changed the original script would be happy to have a credit while the Smithee label declares a sort of distancing from a film project with no one willing to claim responsibility for any of the work. Anyone would have been proud to have worked on Diane. It's another example of Clarke's deft and magical touch with his cast with a special nod to the extraordinary Janine Drzewicki.

Shot on location on analogue video, the image quality on A Follower for Emily feels a tad harsher than studio shot dramas, likely a compromise resulting from having to use more portable video camera equipment and having to light rooms and corridors that have no room for the sort of lighting rigs that studio sets allow. The contrast is certainly crisp, with a decent level of visible detail, and there are no tape blips or other damage to contend with. The soundtrack is clean, with a sometimes crispy edge to the dialogue.

Diane was shot on 16mm film and is a tad soft of fine detail. The contrast is generally well balanced but does occasionally suck in some shadow detail to nail the black levels. The colour is a little muted in places and just occasionally more washed out (see the screen grab in the commentary notes below), but elsewhere is rather pleasing. A fine film grain is visible but the image is otherwise clean and stable, save for a very faint trace of jitter in a couple of shots in the late film hospital scene. The soundtrack has been clearly recorded and mixed and displays no obvious issues.

Janine Duvitsky and Richard Kelley Audio Commentary on Diane [by Camus]

"Only reason!" Duvitski says on her casting, the fact she looked so young. Here was this twenty-three year old cast as fourteen, a middle class girl from the north, playing a Cockney, working class girl. What could go wrong? Practically nothing. The author of Alan Clarke, the anthology of quotes from Clarke's friends and associates, Richard Kelly, plays moderator to Diane herself, Janine Duvitski. She's pitch perfect with no airs or graces, no thespian preciousness. She is exactly who you would imagine her to be and that's a compliment. Kelly's enthusiasm is infectious and both enjoy a rapport with a few odd moments when they adjust to each other's rhythms. There is a strong sense (as expected) that 'the way things were' are terribly missed these days in the film and television industry. The BBC (bless) used to give creative power to those creatives they hired. Executive involvement and gain and naysaying were unheard of. Yes, Clarke could always piss off the brass but on an Alan Clarke film, only one had the final creative say… except for those times when he was royally pounded on. On one of those occasions he went and remade the troublesome TV film into a bona fide movie.

Duvitski mentions that she believed that Clarke's method of directing and shooting was the way it would continue to be. She admits to being spoiled on her first big production ("…an amazing first job actually,") and like Orson Welles she mentions starting bright and "…then it was all downhill from here." Duvitski has been subsequently typecast as a comedic actress and despite her superb dramatic performance in Diane, no one casts her in anything but comedies, a fact she rallies against seeing the same fate beginning to befall her talented daughter.

The play started life being far more deeply religiously themed (until Clarke rewrote it hence the original author's name change) and Duvitski's humanist take on life comes through in spades as she says that religion doesn't help anything; a person after Outsider's own collective heart. Having directed a few films, there are tricks that you pick up. One of them, for my sins, is to always shoot the rehearsal. From non-actors, you can usually get an honest performance if they think they're not being filmed… Clarke played a similar trick on Duvitski for her big scene revealing what had happened between her and her father. He told her (the old rogue) that he needed a 'technical' take and that for 'technical' reasons she had to keep as still as possible and deliver the lines straightforwardly. Duvitski knew how important this scene was (though she didn't know what bullshit her director was capable of shoveling at her) and had privately rehearsed a much more emotive and upsetting performance. Once the 'straight' performance was in the can, Clarke just said "Great, we got it. Next set up…" as Duvitski protested. But Clarke knew he had what he needed and it's still probably the most emotive, effective and underplayed scene in the film.

As I mentioned, Duvitski has not an ounce of pretension and underlines the fact that from her experience actors support each other more than they don't much against the bitchy stereotype of the self-absorbed 'every person for themselves' cliché. She's a breath of fresh air and someone get this woman a great dramatic part, pronto.

Alan Clarke: Out of His Own Light (Part 5) (8:13)

In the first half of this short but splendid episode of the multi-part documentary on Clarke, three of the great Davids of TV screenwriting – Hare, Rose and Leland – brilliantly lament the death of the single TV drama and the post Sky-TV nose-dive in the quality of television drama. Indeed, Hare's opening monologue is so passionately delivered that I can't resist the urge to quote it here: "Undoubtedly today filmmakers make far too few films. The reason most films are so bad is because most filmmakers now are so inexperienced. They've blagged and argued for two years or three years to be allowed to make one film, and by making their one film they're then completely exhausted when they get to the actual position of making it. Because advocacy is what most of us do most of the time now in the film industry – we're lawyers, we aren't creative people. We spend two years talking to financial people to raise money, or we spend two years talking to critics to explain the film." In the second half actor Janine Duvitski talks about getting the lead role in Diane and admits she was spoilt by having Clarke as her first director, while Richard Kelly argues that this was a pivotal film for Clarke.

DISC 6

| |

"Roy had done a lot of research for the script, then Alan did a bit himself by going and working in the hospital for a bit; he got his little white jacket on and did a few stints. I think Tim Preece did too; he was playing the lead, the nurse who has to run all over this ward dealing with these terribly distressed people." |

| |

Production Manager, Michael Jackley |

Writer Roy Minton had first hand experience of what has been called over the unenlightened ages, Bedlam (a nickname derived from the original, contracted hospital name 'Bethlem'), Loony Bin, Funny Farm, Nut House, Cuckoo's Nest, Snake Pit and many more. When I was growing up, you didn't even need a synonym to allude to it. You just needed its location. In South Wales in the 60s and 70s, you just had to use the location 'Whitchurch' in the right context and everyone knew exactly what you meant. Mental Hospital is not much better. It implies a disturbed place right down to its bricks. Like 'This Door Is Alarmed', we know what it's supposed to mean but cannot help wondering what had the door so distressed that a sign had to alert you to it… Minton, deep into alcohol and gambling, was sectioned by those who cared for him. Hours later at 4am, he called home and said the magic words "Get me the fuck out of here…" I suspect this wake up call didn't cure him (it wouldn't have done his family many favours either that early in the morning) but it may have brought him up short enough. This is probably the experience that gave birth to what was to become the melancholic and quietly affecting Funny Farm.

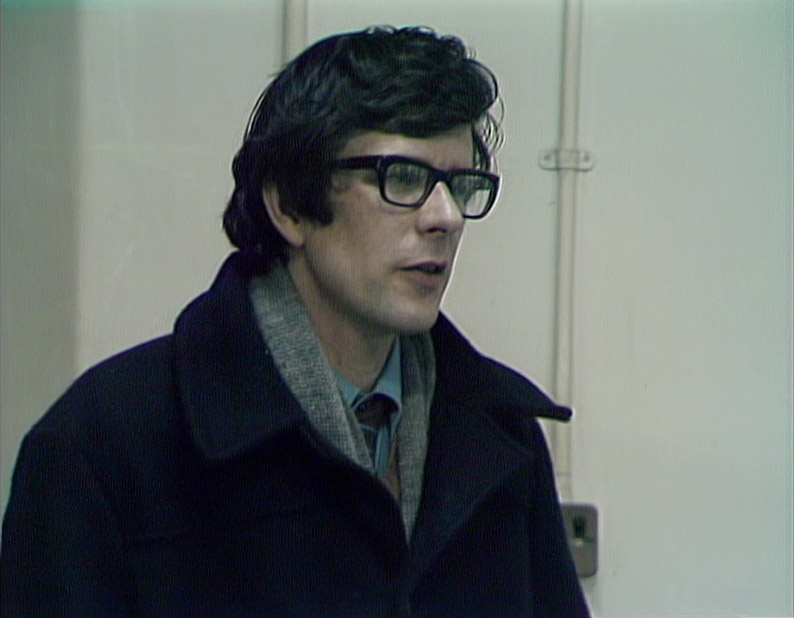

It's a perfect subject for Clarke; people, both nurses and patients, quietly suffering and virtually invisible to the rest of the world. These nurses do a job very few would volunteer for and no one is in this line of work for the money or the kudos. There is little of the former and a dearth of the latter. The commitment required indicates the mettle of someone who really wants to help and make a difference in disturbed people's lives even when those lives may offer neither respite nor closure that doesn't involve a wooden box. Nurse Alan Welbeck (a gentle, hangdog, naturalistic turn from Tim Preece) is disillusioned but professional and earning a pittance which means he has no bus fare, has to cycle a twelve mile round trip every day and cannot even afford sweets for his two children. When Alan turns up for work and enters the office to find two of his colleagues sitting there, for a split second (just for a split second) I thought I was looking at Quentin Tarantino on the right and Stanley Kubrick on the left. I know… You look at it now in the cold light of BBC sets and see long retired actors but just for that magical moment my brain (inspired by the subject of the TV drama no doubt) seemed to see two of Hollywood's most iconoclastic directors, or at least their lookalikes as provided by artist Alison Jackson.

Nurse Alan's many charges are a very diverse gathering without the eccentricities and 'obvious' mental issues of director Milos Forman's and author Ken Kesey's motley crew from One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest. This is a very English mental ward and there is no sense of 'lunacy', no telltale twitches or mannerisms nor is there a sense of 'locked up'. Indeed many of the patients are self-admitted. In fact those that seem to cause Alan the most trouble are there on a voluntary basis. In the group, there's a young man lost in a world of chess, an artist obsessed with speed-oil painting (uh, OK) a fitness fanatic and an older gent who insists on treating everyone to his singing when the mood takes him. Whenever he clears his throat you can almost see fellow patients' jangled nerve endings twang in painful synchronicity. The one whose story is most effective is the character that's given the most unbroken time to state his case. More famous for playing the groundskeeper 'Ned' in the BBC sit-com To The Manor Born, Michael Bilton as Sidney could be that same character ejected from Grantleigh Manor. He tells how - as a long-term gardener for a privileged family - he was riled up to a state of class rebellion by his son–in-law and how this new found self-assertiveness lost him his job after thirty years of service. To have the foundations of your entire life pulled from underneath you create the very cornerstone and attendant probing roots of mental illness. Author Milan Kundera suggested that changing the name of where you live initiates the first signs of madness. Wiping out a thirty-year routine is more than comparable. Each man in the ward has a unique problem sharing only the physical space with others in which to battle it. The only woman we see is the foul-mouthed, fag-scavenging Joyce (Helena McCarthy) who's always trespassing on the men's ward. Nurse Welbeck (Preece) deals with each man with a sensitivity bordering on sainthood. One patient, forever waiting for the doctor, in pajamas missing his clothes, does a runner and Welbeck's subsequent care is notable right down to the tucking in of the sheets. You'd think a sane man's patience would be fraying at the edges. Where Alan is most troubled is in his financial commitment to his family. His awful choice is (1) do a job he loves at barely enough money to scrape by or (2) chuck it in for a depressing, soul-destroying factory job which pays twice as much… The patients are sympathetic but they have their own problems. That is why they're here.

Clarke's film is a snapshot of a system that begged for some kind of infrastructural reform. The commitment of the people employed is never questioned but the state's resources are woeful and Alan finds himself frequently standing in for others at short-staffed departments. As the disgruntled nurse gets on his bike for his weary six mile ride home, in the rain, we are given some sobering statistics which of course are now way out of date but the logical thrust behind them has probably remained the same all these years later. There will doubtless be a note on the recording medium in the Sound and Vision section but I just wanted to flag the pulsing purple and green highlights that pop up whenever 80s video had to deal with motion and highlights. Film people, for this technical reason, are often dismissive of video, particularly early video, citing the superiority of film's dynamic range but you get a sense from Clarke that the physical medium is utterly unimportant. Whatever medium gave him the scope to do what he wanted to do, how he wanted to do it, was the best choice for him.

It struck me quite late on in reviewing Clarke's oeuvre (actually during this one, my final review) that he and his writers take absolutely no notice of the standard paradigms in scriptwriting and therefore filmmaking. In almost all filmed drama, there is a character with a problem that needs solving and the film is the stage, the context in which he/she solves this problem and either succeeds or fails but in both cases the story ends. Clarke's stories, extraordinarily, don't end. I cannot believe I have just come to this conclusion. Even the gunshot at the end of one his more famous films is not an ending but part of an ongoing escalation. Yes, his films feature characters but characters that don't care that there's a camera and expectations trained on them. Diane's success in the eponymous film is that we do not see her in the final scenes. How many characters in fiction are allowed to be absent for their big moment? Clarke's style is observational, an invitation to enter the life of someone you may never, ever meet in your own life presented in the simplest way he knew how. There's no showy cutting, no fancy camera movements. If anything, Clarke's style became simpler the more films he made. The Steadicam wasn't a sexy piece of kit, it was a device that enabled ordinariness in fluid continuity. Alan Clarke was an ghost-director, a director who attempted to direct invisibly, a real screen reductionist. Stylistically, he became almost ascetic and that's the last thing you can say about Alan Clarke the human being without a lens in front of him. His style is no-style, it's an emphatic, empathic calling card, laying a life down in front of you for you to investigate on your own terms.

His political bias is well known but through the early work, it's not often easy to discern on a surface level. Let's ignore the accusations of right-wing leaning from his cameraperson colleague about Psy-Warriors which may or may not be a valid reading but it's clear that Clarke favours the disadvantaged end of the pool. His socialist credentials are loud and proud because you get the strongest sense that he is astounded that people could choose to live any other way. But he still manages sympathy for monsters because of course there are no such things. They are human beings with beliefs that deify the acquisition of power and wealth and crush the less fortunate beneath their heels. Clarke manages to get under their skin too. Ultimately Alan Clarke is a director of human beings, laying bare their foibles, frailties and fancies. He invests characters in fictitious scenarios with a realism that is almost sleight of hand. His time and indeed the golden television age have passed so we will not see his like again and so once more I applaud those that brought this wonderful box set to such glorious life.

Note: This review contains some major spoilers and should be read with caution or after you've seen the film.

The story of what happened with the original TV version of Scum is now well known even outside the cosseted world of the British film and television industry. Written by Roy Minton and directed by Alan Clarke, the project had been green-lit as part of the prestigious Play for Today series by BBC1 controller Brian Cowgill, but following his departure and replacement with the more cautiously minded Billy Cotton, problems arose. BBC managing director Alisdair Milne believed the film was misleading in its presentation of drama as documentary realism and cuts were requested. Home Office and prison officials were called in to view it, and the decision was then made by Milne, with Cotton's full backing, that it should not be transmitted, despite having been already scheduled and advertised. It remained a banned work for the next fourteen years, and even then received only a single screening after the director's death as part of the BBC2 season celebrating his work. Despite this sizeable initial setback, Clarke and Minton refused to give up on the project, and two years later re-shot it on 35mm for a cinema release. The result went on to become one of the most successful and talked about British films of the year, and one that to this day remains an iconic and searingly powerful film experience.

Most of those coming to the original version of Scum, myself included, will likely have done so having already become familiar with Clarke's feature film remake. This inevitably brings baggage to the viewing that is unfair and unfortunate. In my case the feature version was a key film of my youth, a work that genuinely affected my attitude to cinema in general. It was also my first exposure to the work of Alan Clarke. To fully appreciate the original's qualities, it is thus important to put that aside and to cart yourself back to the 1970s and imagine just what it would have been like to tune in at 9.25pm and be presented, out of the blue, with a film such as this. Had it actually been shown, of course.

For the uninitiated, Scum is set in a borstal. It's a word that may mean little to younger viewers, the main reason being that the borstal system itself was abolished by The Criminal Justice Act in 1982. Borstals were institutions in which young offenders were incarcerated under a strict regime of harsh discipline, work and education. They were intended to build character, teach their inmates respect for authority and install in them a strong work ethic, but by the 1970s it was becoming clear that in a number of borstals control was being maintained by a regime of violence, bullying and racism dished out both by staff and inmates alike. Into just such an institution arrive three new unfortunates: tough, street-wise Carlin has been transferred from another borstal after hitting a warder; quiet, introverted Davis ran away from a minimum security establishment and was promptly recaptured; while black newcomer Angel is unprepared for the racism he is to be subjected to by his white custodians and fellow prisoners. Carlin in particular becomes an immediate focus for negative attention, his reputation as a 'daddy' – an inmate in an unofficial position of power attained and maintained through a combination of violence and gangland-style intimidation – having arrived ahead of him, which brings him into immediate conflict with the warders and the incumbent daddy, Pongo Banks.

This original version of Scum is noticeably more low-key than its later feature film brother. Many of the performances lack the striking confidence they have in the film and there are none of the compellingly executed 'walking shots' that were to become a trademark aspect of the director's visual style. But this approach also creates an intimacy with the characters that is immediately engaging and has a matter-of-fact quality that in some ways enhances its potent air of realism.

The story development is almost identical to the feature, as is much of the dialogue, though here it inevitably lacks the expletives that became key components of some of the feature's most oft-quoted lines. Individual scenes sometimes unfold differently here and there are a small number of location shifts, but those familiar with the feature will still feel at home. Where the two do part company a little is in the second half – in this version Carlin plays an increasingly minor role, and in a compelling scene that did not make it into the film (due to Ray Winstone being uncomfortable with it, a decision he later regretted) he takes on a 'missus', a young inmate he keeps around for company and sexual gratification. This leads to a scene also unique to this version in which the increasingly despairing Davis goes to Carlin for advice, but is dismissed out of hand when he feels unable to talk in front of this now ever-present companion. This tends to paint Carlin in a more callous light, making his own attitude a contributory factor in Davis's eventual suicide and suggesting a different motivation for Carlin to lead the riot that follows, springing instead from his anger at himself for allowing this to happen.

As Carlin, Ray Winstone was making his acting debut here, and though he lacks the forceful authority he displays in the remake, his more obvious youth and naturalistic delivery really sell the authenticity of his character and situation. This also applies to many of the supporting roles, whose increased confidence in the feature surely resulted from the actors, each by then more experienced, being able to take a second shot at characters with which they were by then familiar. The character that differs most noticeably in two films is without doubt Archer, the cynical intellectual that Carlin befriends and the mouthpiece for Roy Minton's own views on borstals and the negative effects of criminalising the young. Played to scene-stealing perfection by Mick Ford in the remake, the interpretation here by David Threlfall is less animated and lacks the cocky world-weariness that Ford made central to his interpretation, but Threlfall is just as compelling in his quieter way and certainly is less of a sore thumb standout in this institution than his successor.

Initially it's Carlin who drives the narrative forward, the beatings and humiliation he endures leading to the inevitable but still hugely cathartic scene in which he takes Pongo down and establishes himself as the new power on the block. His position is consolidated when he defeats the intimidating black boss of B-wing by swinging a weapon in a fight that his opponent was under the impression was going to be settled with fists. It's in this scene, as in the earlier one in which Angel is beaten by Pongo and then given a nasty dressing-down by a warder, that the true nature of the racist insults spouted many of the white characters become clear – far from being an expression of genuine racial hatred, they are used as yet another method of intimidation and control, a bullying put-down employed solely to belittle and humiliate. That it is so direct will no doubt cause some newcomers to balk a little at these scenes, but it never feels gratuitous, even at its most unpleasant.

As the film builds, simmers and finally explodes, the viewer is left with the inescapable sense of a system that does not strengthen character nor install respect for authority, but which brutalises and destroys, takes young men who have broken the rules and moulds them into hardened criminals. If the TV original never quite captures the searing impact of the feature version, then this is only right – the demands and expectations of a cinema feature are different to that of a TV play, and it's a sign of the screenplay's strength that no significant changes had to be made to story, character or (toughening up aside) dialogue to reshape the film for cinema release. As a work of its time, a TV play made for screening on a mainstream TV channel, Scum is still an astonishing achievement. That it was banned and buried by the people who should have been celebrating this is scandalous, but that there is nothing being produced by any UK TV channel now that comes even halfway close to matching the film's boldness, ambition and commitment, is ultimately depressing.

Funny Farm was shot on analogue video and is in good shape, though lacks the punchy crispness of the studio footage from To Encourage the Others – you'd have little trouble spotting that this was recorded on video tape. The contrast is crisp and the colours rather well preserved, and once again there are no signs of tape damage. The soundtrack is very clear, the dialogue especially so, and the inevitable treble leaning is not so pronounced here. Again, there are no signs of damage in this area.

I'm guessing that Scum presented a greater challenge to the restoration team than some of the other works here, although it's very possible that the slightly grubby aesthetic here was a deliberate choice on the part of Clarke and his DP John Wyatt, or one partially forced on them by their location. With this in mind, this is still a reasonably solid transfer – the colour has an earthy bias and the some detail does get pulled in by the solid black levels, but the realistic lighting and colourless environment are defintely factors here. Pleasingly, the image is still clean and free of damage.

David Leland Introduction on Scum (2:53)

In this gem of an intro as part of BBC2's Alan Clarke season, David Leland enters the BBC vaults and, holding the film can in which the original Scum was interred, makes a case for the widely held suspicion that the reason behind the ban was political censorship. He then slyly encourages you to record this screening for posterity.

David Threlfall, Margaret Matheson, Phil Daniels and Nigel Floyd Commentary on Scum

Ported over from Blue Underground's The Alan Clarke Collection DVD set, this commentary features producer Margaret Matheson and actors David Threlfall and Phil Daniels, and is moderated by critic and broadcaster Nigel Floyd. The first ten minutes consist of a general discussion on how the project came into being, but the comments eventually become screen specific as background detail is supplied on individual scenes and characters, with plenty of interesting anecdotes thrown in about the production itself. David Threlfall in particular appears to be having a good time, though at one point Phil Daniels razzes him a tad by stating cheerfully about the feature remake, "We had a really good Archer!" Later on, Matheson provides some very detailed information on the banning of the film, and all of the participants seem united in their admiration of Clarke as a director and colleague. Consistently engrossing and with no dead spots, this is a very fine, very useful special feature.

Tonight: Scum Discussion (1978) (10:51)

Broadcast on 23rd January 1978, this extract from the show Tonight looks at the banning of Scum and pits Managing Director of BBC Television Alisdair Milne, who enforced the ban, against Guardian TV critic Peter Fiddick, who opposed it. A useful record of the arguments for and against made at the time.

Arena: When is a Play Not a Play? (1978) (46:02)

At a time when the terms drama-documentary, docudrama and even mockumentary have evolved into sub-genres in their own right, this episode of the BBC arts show Arena, which explores the potential pitfalls of drama whose realism can potentially fool people into believing that they are watching a documentary, makes for intriguing viewing. Times have changed, and a wider awareness of the grammar of film may make it surprising that G.F. Newman's superb 1978 drama Law & Order – which included corrupt policemen and abuse of a prisoner – was once criticised for this very misconception, but I distinctly remember the furore at the time, and the programme is one of several under discussion here. The banning of Scum is also covered, and Alan Clarke is interviewed about the film and the BBC's decision not to screen it, while Alisdair Milne repeats his objections from the Tonight extract above. There are plenty of interesting interviews here and a number of pertinent extracts from TV works that fall into this category (including Jim Allen's excellent The Spongers), the most surprising of which sees documentary filmmaker Dennis Mitchell praise Ken Loach's groundbreaking Cathy Come Home as a beautifully made film but condemn it as manipulative and propagandist, which prompts an excellent response from the film's producer (and later director of note) Tony Garnett.

Alan Clarke: Out of His Own Light (Part 6) (25:37)

It's perhaps not surprising that the lion's share of this episode of the documentary is devoted to Scum, but there's almost a sense that Funny Farm is being dealt with as quickly as possible in order to get onto that. Personally, I'd have liked to hear more about the cuts enforced by the BBC on Funny Farm and the resulting conflict, though this does get some discussion in the accompanying book. I've no such gripes on the coverage of the making and banning of Scum, which is detailed and comprehensive and includes revealing contributions from producer Margaret Matheson, author Roy Minton and actors Ray Wintone and Phil Daniels. How Winstone landed the role of Carlin is up there with Tim Roth's chance casting in the lead of Made in Britain, and both he and Daniels have some interesting views on Clarke's directorial style. Producer Clive Parsons recalls how the feature film remake came about and admits that some still believe that the original was 'purer', while Winstone (who also prefers the original) explains why a key scene involving Carlin's 'missus' is not in the remake.

|