| |

“For instance, on the planet Earth, man had always assumed that he was more intelligent than dolphins because he had achieved so much – the wheel, New York, wars and so on – whilst all the dolphins had ever done was muck about in the water having a good time. But conversely, the dolphins had always believed that they were far more intelligent than man – for precisely the same reasons.” |

| |

Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy |

When it comes to movie titles, screenwriters do seem to like animals to have their day. Just from memory, I can recall that over the years we’ve had The Day of the Jackal, the Locust, the Beast, and the Triffids (technically they’re plants, but sentient ones). A quick check confirms we’ve also had short films about the Day of the Dog, the Cat and the Coyote. Then we can get started on the animals that get their own Night, which include the Iguana, the Wolf, the Lepus (giant rabbits – hilarious), the Grizzly, the Rat, the Cat, the Dog, the Sharks, the Seagulls, the Eagle (superb) and, if you’re stretching the definition of animal into the realms of the mythical, the Phoenix. In the first of these two camps sits the 1973 The Day of the Dolphin, written by Buck Henry and directed by Mike Nichols, who when they first worked together in 1967 struck gold with a little film called The Graduate, which they followed in 1970 with a film adaptation of Joseph Heller’s masterful novel, Catch 22, which is still a bit of a favourite with the Outsider crew. So what of this third Henry-Nichols collaboration? Ah, well, that appears to be very much a matter of taste.

I first saw The Day of the Dolphin only a few years after its cinema release in less than ideal conditions (a TV screening of a cropped 4:3 print) and remember being drawn to it primarily by the pedigree of his writer-director team and the fact that it starred George C. Scott, of whose work I was already a big fan. I distinctly recall admiring Scott’s performance, as expected, but also recall having considerable trouble swallowing what I back then regarded as a rather daffy central concept. A lot of time has passed since then and I was genuinely curious to see how I’d react to the film so many years and movies later. I was still apprehensive – there’s a bloody good reason that I found a key aspect of the film hard to swallow all those years ago – but absolutely willing to give it another go. Opinions tend to change over time, right?

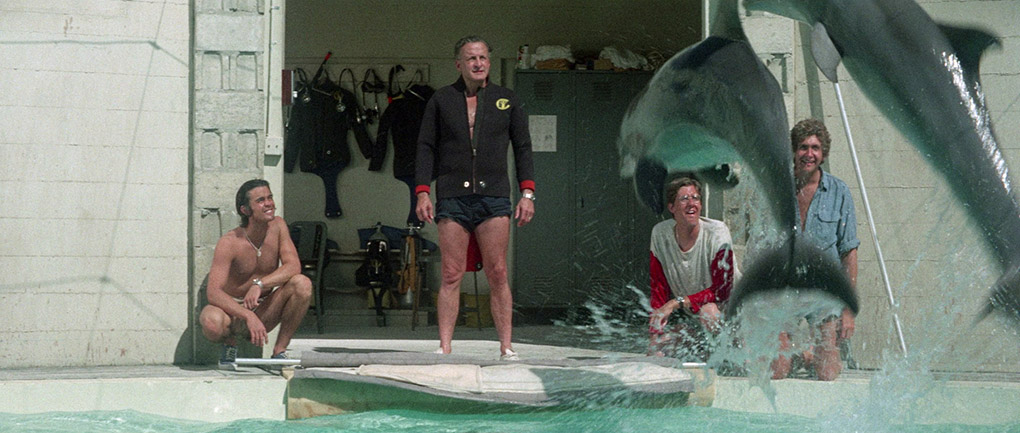

It begins with an address to camera by marine biologist Jake Terrell (George C. Scott) about the unique physiology of the dolphin, an intriguingly unusual and fourth wall-breaking way of opening a film. This is intercut with an ultra-slow motion shot of a dolphin leaping out of the water with a ball that it tosses to a small group of onlookers, which is followed by footage of a writer named Curtis Mahoney (Paul Sorvino) watching a demonstration of the animal’s ability to recognise shapes and respond to commands. It’s then revealed that Jake is actually giving a talk to an audience consisting almost exclusively of what would once have been described as stereotypical American housewives. According to the cast list, they’re members of something called a women’s club, a theoretically all-female gathering that does make it easy to spot the stern-faced Curtis sitting in their midst. Hmm, what’s this man’s game? When the talk concludes, Jake is gently pestered by Harold DeMilo (Fritz Weaver), the genial buffer between Jake and the Franklin Foundation that is the source of his funding. Harold has concerns about the amount of money being swallowed by the secretive work being carried out at the isolated shoreside Terrell Marine Centre, which we soon discover is run by Jake, his wife Maggie (Trish Van Devere) and a small team of enthusiastic youngsters. It’s here that Jake has been working for years with a dolphin named Fa* (short for ‘Alpha’), which they have been training to speak and respond to English words. And this is where I had, and still have, a bit of a problem.

A key element of successful horror and science fiction cinema lies in the suspension of disbelief, and this has to take place within the context and framework of the film in question. When it works, you should be able to – at least for the duration of the film – throw whatever real-world beliefs you have out of the window and buy into those being proposed in the story. It’s this that enables a movie to convince us that a man could meld with the DNA of a fly when testing a teleportation machine, that an innocent young girl could be possessed by the demon Pazuzu, and that a doctor could create a new life by stitching body parts together and firing up the creature with a lightning bolt of electricity. With such extreme examples in mind, what could possibly be hard to swallow about English-speaking dolphins? If that question raises even a hint of a smile, then you likely already have an inkling of my issues here.

As far as I’m aware, the oft-proposed notion that dolphins are as intelligent as humans was born in part from the fact that their brains are of a similar size to ours, and there is no question that dolphins are remarkable animals with their own complex methods of communication and navigation. But it’s also worth remembering that their mouths are a very different shape to ours and they lack the facial and lip flexibility that are key to the pronunciation of so many of the sounds and syllables of our language. I’m guessing their vocal chords are also a weeny bit different to our own. And what I’ve so far seen of the real world efforts to persuade dolphins to imitate the voices of their trainers is, to put it politely, less than convincing.

Adding to my difficulty – and I once again feel the need to stress that this my issue and one that a fair few others will likely not share – is that the film never feels like the science fiction drama that it technically is, being more akin in its feel, its look and its characters to the reality-based conspiracy thrillers that helped make early 1970s American cinema so exciting. This is seemingly confirmed by the direction the plot eventually takes, its late arrival triggering a shift in tone that transforms an intriguing character drama (worry not, I’m getting to the positives soon) into a hurried and underdeveloped espionage thriller. I’ve not read a translation of Robert Merle’s Un animal doué de raison, the novel on which Buck Henry’s screenplay is based, but I gather that the film has stripped that story of its cold war politics, substituting the plan to exploit the animals for nefarious purposes by a private group with an end game but no manifesto, and that’s about as much as we learn about any of them. To discuss their plan in any detail, such as it is, would mean getting into spoiler territory, but I will note that I was able to pick sizeable holes in it, which did little to help its overall credibility.

None of which, I should point out, would normally be a dealbreaker, as some of my favourite films go down the “what if?” route and test the boundaries of what we’ll swallow within the context of an otherwise reality-based story. The breaking point for me comes when we hear Fa speak. Presumably, after considering the above-mentioned issues regarding the differences between the mouths and vocal abilities of dolphins and humans, the filmmakers took the decision to use the familiar squeaks and cries of the animal as the basis for how these spoken words might sound. And unfortunately, when Fa speaks what I heard was not a the voice of a dolphin, whatever that may be, but that of an adult human trying to imitate a cloying baby.** The very moment Fa refers to Jake as “Pa” – or should that be “Paaaa” – in this voice, my suspension of belief packed its rucksack and went for a hike. Like I said, this is a personal thing that many will not share, and in the special features on this disc, two of the contributors recall shedding a few tears at a moment that I had a somewhat different response to.

All of which is a shame, as the film is otherwise built on solid foundations and there remains much about it that I found myself intrigued and impressed by. Absolutely central to this is Jake and his young team, all of whom are well cast and naturalistically played, convincing completely as individuals dedicated to a common cause, while their affection for the dolphin they have worked with for so long comes across as completely genuine. The paradisical location in which their operation is located also makes complete sense within the context of the story, being close to the dolphin’s natural environment and distant enough from prying eyes to allow them the privacy their work requires. It comes as no surprise the George C. Scott is excellent as Jake, seriously imposing when frustrated but able to sell completely the notion that he and Fa have an almost spiritual connection – when the two swim together in one of the film’s most quietly captivating scenes, there’s an almost romantic undercurrent to the interplay, one that renders irrelevant the fact that the two are from different species. Having said all that, if Harold wants to know where the money’s going, he might start by asking Jake why he needs a bank of twelve expensive reel-to-reel tape recorders to record the sounds made by a single dolphin, except to switch on one-by-one to visually enliven a key piece of exposition.

It helps that Fa is almost as well developed a character as some of his human counterparts, pining for a mate that he immediately swims in harmonious circles with as soon as the two meet, then losing his rag when separated from her, action taken by Jake after this union prompts Fa to lose interest in his teacher’s experiments. For me, the message was clear – what this dolphin really wants is to live and swim and converse with its mate in its own language, then father new dolphins like the one we see born in the opening sequence. He’s not abandoning Jake’s teaching because he’s distracted, as Jake seems to believe, but because this is what dolphins are supposed to do if left free to follow their own instincts. When Jake separates Fa from Bi (pronounce ‘Bee’ and short for ‘Beta’), he is putting the continuation of his work above the welfare of the animal he has become so attached to, sitting for hours on end by the pool until the isolated Fa capitulates and starts using English words again as he’s been taught. It’s at this point that I had my biggest doubts about the ethics of the work being conducted by Jake and his team and found myself recalling Louie Psihoyos’s eye-opening documentary, The Cove, in which former dolphin trainer Richard O'Barry experienced an epiphany and became a campaigner against a profession he now regarded as cruel and the whole notion of keeping these animals in captivity.

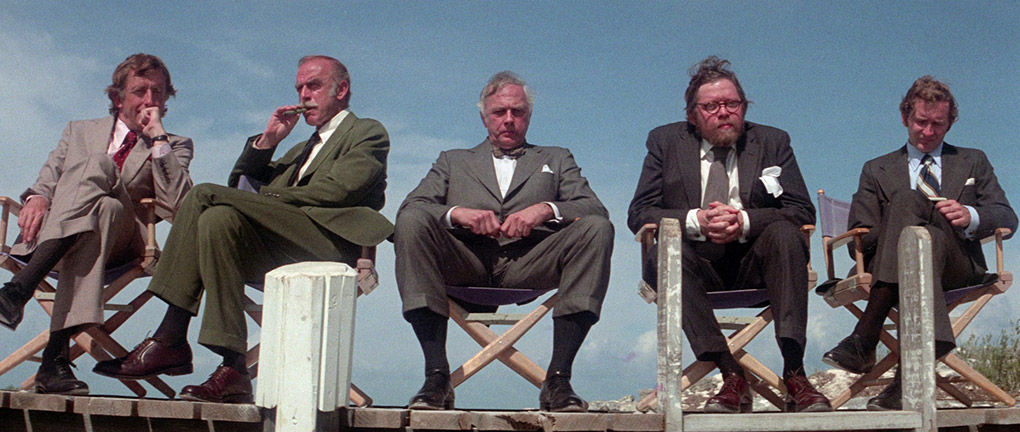

I like that Nichols and Henry chose to spend the first half almost exclusively with the team, its work, and Jake’s efforts to keep the funds flowing and nosey outsiders at a distance. I would also suggest that the involving nature of these scenes is a key reason for the critical dissatisfaction with the late-in-the-day switch to espionage thriller, as quite frankly the film was doing well enough without it. It seems clear that Jake and his group were intended from the start to be the prime focus here, and it’s they, along with money man Harold DeMilo, who are the most convincing as real-world characters. As inquisitive writer, Curtis Mahoney, Paul Sorvino is certainly enjoyable to watch, particularly when it becomes evident that his true intentions may not be what we have been led to believe, and it’s nobody’s fault that when he’s nosing around secretly in the island greenery, there’s more than a whiff of Oliver Platt’s crocodile enthusiast Hector Cyr in the later Lake Placid about him. The suspect group of backers from the Franklin Foundation, on the other hand, are little more than thinly-sketched cyphers, a band of essentially nameless, off-the-peg capitalist villains that includes a cartoon ex-military type with a heroic moustache who never appears on screen without a large, and at one point comically phallic, cigar between his fingers.

Being a studio production and the work of talented industry professionals, The Day of the Dolphin is certainly a handsomely mounted production. Rosemary's Baby, Bullitt and WarGames cinematographer William A. Fraker’s scope lighting camerawork is consistently impressive, Richard Sylbert’s production design helps to sell the Terrell’s compound as a real and functioning marine research centre, and Georges Delerue’s richly emotive score includes a triumphant theme that borrows from his own Grand Choral, a glorious piece composed for François Truffaut’s La nuit américaine earlier the same year. On its release, the film, with a few notable exceptions, was not well reviewed, and director Mike Nichols and screenwriter Buck Henry all but disowned it, which of course makes it perfect for critical re-evaluation and championing as a once criminally misunderstood work, and I so wish I could get on board with this viewpoint. Some of my issues with it are personal – dispense with the whole dolphin speaking English element, particularly in that voice, and doubt I’d have a problem with the otherwise involving first half – but I’ve yet to hear a convincing defence of the anaemic espionage elements around which much of the final third is built. Others will disagree and that’s absolutely fine, and in spite of my gripes, there is still much in the film that I admired and enjoyed. It was certainly an interesting one to revisit, though I can’t see myself popping it back into my Blu-ray player again any time soon.

Sourced from a 4K restoration by StudioCanal and framed in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, the 1080p transfer here gets off to a slightly bumpy start, with George C. Scott's address to camera being slightly soft on detail, but otherwise the results are very pleasing – once again, tne screen grabs here don't really do it justice. The daytime exteriors in particular look lovely enough to make me wish I was at the Terrell Marine Centre right now, basking in the sun to the sound of the surf, and far away from the noise of traffic and Covid and other humans. Sorry, got lost in a little daydream there. Colour in these scenes is wonderfully naturalistic, the contrast pitch-perfect and the detail crisp, and even when the light levels drop the integrity of the image is maintained, albeit with sometimes deeper shadows and a colour bias appropriate to the location lighting. The picture stays clean throughout and a fine film grain is visible. A really nice job.

There are two soundtrack options here, Linear PCM 2.0 stereo and DTS-HD Master Audio 3.0 stereo. Theoretically, the only real difference between them should be that dialogue and effects spread across the two main front speakers on the LPCM track emanate primarily from the centre speaker on the DTS. On my system, however, the DTS track sounds richer and has a more robust bass response, and as a result felt more ‘cinematic’, although music reproduction is of a similar quality on both tracks. For some reason, the DTS track also triggered the rear speakers on my home cinema amp, but the sound remained confined to the front of the sound stage.

Optional English subtitles for deaf and hearing impaired humans and English-speaking dolphins are available.

Selected Scenes Commentary with Sheldon Hall (32:40)

Academic and film historian Sheldon Hall examines the opening scenes of a film he admits to loving, and also takes a brief look at a later sequence set in the Franklin Foundation building. Our difference of opinion on aspects of the film aside, this is an interesting piece of sequence deconstruction that also looks at how the film was promoted on both its original release and re-release the following year, as well as touching on the sound design and the dissatisfaction with the film later expressed by Mike Nichols and Buck Henry. Just occasionally, I had a sneaking suspicion that Hall reading meaning into elements that were not specifically designed to be interpreted that way, but as this is something we all – myself included – do from time to time, I have no problem with this.

Jon Korkes: Days of My Life (43:46)

Actor Jon Korkes recalls the series of chance events that saw him cast first in a small role in Catch 22 and then as Terrell team member David in The Day of the Dolphin. As you might expect from the length that this interview runs for, he has plenty of memories of the filming to share, including being encouraged by Mike Nichols to bring his dog with him for the three-month location shoot in the Bahamas, shooting a sequence with the dolphins that had to be postponed when things got a little scary, the pleasures and difficulties of working with George C. Scott, and more. He recalls how the more frightening aspects of the documentary Blue Water, White Death – which for some inexplicable reason Mike Nichols chose to screen for the cast and crew on their weekly movie night – only hit him when he later saw Jaws, which had the effect of traumatising him so much he’s not been in the ocean since. He also tells an intriguing story about a dinner party hosted by George C. Scott on board a rented yacht at which Scott became increasingly drunk and agitated as the evening progressed, confirmation of which is provided elsewhere in the extras. Overall, though, he remembers it as one of the best times of his life.

Michael Haley: Moon Over the Bahamas (39:24)

The film’s second assistant director, Michael Haley, recalls being a commune hippie and having no interest in working in film until he responded to an ad for a general assistant on Outsider favourite, The Honeymoon Killers, which led him into acting, on to second and first assistant director roles and eventually producing. I enjoyed the hell out of this – Haley is a riot, a product of 60s counterculture who has found a niche within the system but has retained a keen sense of playful rebellion, and this comes across in spades. Every story he tells makes for entertaining listening, including a couple about George C. Scott and a ton about the sometimes colourful ways he found of mooning Mike Nichols every Thursday, which included a gag that ruined a shot that Nichols had been convinced by an in-on-the-gag Scott was a one-chance take, and another in which he parasailed naked past the director and then ended up gliding past a beach full of doubtless startled tourists. There’s not a dull moment here and I could have listened to Haley all day – even the intermittent wobbling of the camera and sudden exposure shifts (probably from shooting on auto exposure with the tripod seated on a flexible wooden porch) seemed to add to the anarchic feel.

Archival Interview with Buck Henry (12:20)

Framed 4:3 and in standard definition, this archival interview sees screenwriter Buck Henry look back at the process of adapting a novel that he describes at one point as “a giant sprawling mess with two unbelievable pieces in it,” and if you thought the very notion of talking dolphins is a bit of stretch, just wait until you hear what Henry chose not to include. There’s plenty of real interest here, and his subsequent disdain for the film does occasionally slip through, notably his claim that it’s only any good when it captures the natural beauty of the dolphin. He also confirms a story told by Jon Korkes about the dolphins that played Fa and Bi swimming away after completing their final shot in the film. “Now if only we could get certain actors to swim out to sea and not come back,” he adds, just a tad cynically.

Archival Interview with Leslie Charleson (6:48)

Actor Leslie Charleson recalls landing the role of dolphin research team member Maryanne, working and living together on location with the cast and crew, getting along well with fellow female team member Victoria Racimo, not wanting to be in the same vehicle as the opera-singing Paul Sorvino, and more. She seconds Jon Korkes’ story and the dinner party hosted on his yacht by an increasingly drunk and belligerent George C. Scott, but does so from an alternative perspective and with a few additional details.

Archival Interview with Edward Herrmann (13:07)

Edward Herrmann talks about landing the role of team member Mike and jumping at the chance to spend three months in the Bahamas with Mike Nichols and George C. Scott, an actor he describes as “our Olivier.” There’s a long story about swimming with a dolphin named Big Mama, another about a perennially drunk props manager, and he confirms a tale told by others about Nichols bringing in his own chef to cook for the cast and crew, though I gather from Charelson’s interview that his repeated usage of the same two varieties of fish soon wore thin for some of them. Herrmann also wonders if Henry and Nichols ever really knew how to resolve the story, and reveals that halfway through the production Nichols was openly wondering why he was making this film.

Theatrical Trailer (3:09)

Oh no, no, no. There a spoilers aplenty in a trailer that reveals almost the whole bloody plot in precis form. What were these people thinking? If you’ve not seen the main feature, don’t go near this thing of evil until you have.

Larry Karaszewski Trailer Commentary (3:43)

Screenwriter Larry Karaszewski – he of Ed Wood, The People vs. Larry Flynt, Dolomite is My Name – sings the praises of a film he holds in the highest regard, being the second contributor to the special features to admit tearing up at the film’s finale. He also talks about George C. Scott and his wife and co-star Trish Van Devere (“sort of a classy version of Charles Bronson and Jill Ireland”), and confirms that the film was originally slated to be directed by Roman Polanski, who was forced to abandon the project after his wife, Sharon Tate, was murdered by the Manson Family.

TV Spot (0:31)

A complete dud of a sell based around the moment when Fa says “Fa love Pa,” the memory of which prompted Buck Henry in his interview above to state in irritation, “boy have I suffered for that.”

Radio Spots (1:26)

Three very different radio spots, all of which are better than the TV spot above, though the third does contain a bit of a spoiler.

Image Gallery

66 screens of variable quality publicity stills (why is it the monochrome images look so much nicer than the colour ones?), colour-enhanced lobby cards, Japanese press book pages and an intriguing variety of posters

Booklet

Following the movie credits, this booklet kicks off with a spirited defence of the film’s qualities by the knowledgeable Neil Sinyard, whose irritation at the previous critical hostility is clear and whose musings on a couple of points are not quite in sync with statements made by others elsewhere on this disc. Snippets from articles about the production and interviews with Mike Nichols and executive producer Joseph E. Levine are followed by extracts from an interview with the film’s female lead, Trish Van Devere, in which she talks about the film and working with her husband, George C. Scott, as well as his and Marlon Brando’s refusal of their Best Actor Oscars (Scott for Patton, Brando for The Godfather). Next is an extract from the English translation of Robert Merle’s source novel Un animal doué de raison, in which a reporter interviews the dolphins Fa and Bi and receives articulate and thoughtful answers. It’s something that I have no doubt would have looked way too like Dr. Doolittle had it been realised on screen, and it acts as a handy reminder that what works on the printed page will not necessarily also work in a movie. Finally, we have extracts from three contemporary reviews offering a rather pleasing mixture of opinion on the film. The booklet, as ever, is impressively produced and attractively illustrated with promotional material.

A well-made film with fine performances and impeccable technical credits, but whose central conceit I just couldn’t get on board with and whose later espionage twist I’m far from the first to regard as underdeveloped and uninvolving. Others will disagree, and for them especially, this is an easy disc to recommend, for the quality of the transfer and an engaging and informative set of special features.

|