|

Fans

of the ghost stories of M.R. James – and what serious reader

of horror fiction isn't? – will be well aware of his favourite

plot, which introduces us to a sceptic who is later prompted

to reconsider his unbelief when directly exposed to some

terrifying supernatural event or apparition. It's at the

core of many of his stories and the two most celebrated

film adaptations of his work, Night of the Demon

(1957) and Whistle and

I'll Come to You (1968).

Night

of the Eagle is certainly in the M.R. James mould

but was actually based on the novel Conjure Wife

by Fritz Leiber Jr., a book I confess to not having read and whose adaptation here I am thus unable to testify the accuracy of. Whether Leiber

himself was influenced by James I've been unable to confirm,

but various sources note the influence of both H.P. Lovecraft

and Robert Graves on his earlier work and Carl Jung on

the later, and a recurring theme in his stories involves paranormal activity in modern urban settings rather than

the gothic isolation of more classic horror fiction. Conjure

Wife has in fact seen three film adaptations, with

Night of the Eagle preceded by the 1944

Weird Woman and followed in 1980 by a more light-hearted

take on the story, Witches Brew.*

Night

of the Eagle takes its subject seriously from the

start and wastes no time establishing its credentials – the

very first words of dialogue are "I...do...not...believe!"

emphatically stated by professor Norman Taylor of the Hempnell

Medical College as he writes them large across the blackboard.

These four simple words, he informs his students, are the

best defence against all of the superstitious nonsense out

there that gets in the way of hard science. He's right,

of course, but this is not real life but a horror film, and

we thus know he's setting himself up for a dramatic about-turn

later on.

At

this point, things are going swimmingly for Norman. His students

get the best grades in the school and it looks like he's

up for promotion. He has a nice house, a sporty car, and

his wife Tansy adores him. Not everything is picture-book

perfect, however. One of his students, Margaret Abbott, has a serious

crush on him, making her underachieving boyfriend Fred Jennings seriously

jealous. But none of this bothers Norman, who responds by putting Margaret

in her place and ordering Fred to pull his socks up. There's

also some jealousy amongst the wives of the other professors

– after all, Norman is the new kid on the block and their

husbands are surely more deserving of the promotion than

him. But they all get together every Friday evening and

play bridge nonetheless, a cosy and pleasant little academic

community.

Following the latest bridge evening, however, Tansy seems

unusually agitated. She's searching the living room for

something, a shopping list with a phone number on she claims,

but her urgency and determination suggest it's something

more valuable. The only thing is, she's looking for it in places

that it couldn't possibly be. When

she later finds what she is seeking she immediately

burns it. What is it? Ah, you'll have to see for yourself.

Norman,

meanwhile, is upstairs looking for his pyjamas, but the

drawer in which the clean ones are stored is jammed. Further

investigation reveals a small jar containing a dead spider.

A BIG dead spider. As you might imagine, he has a few questions

for his wife. He has a lot more the next day when he discovers

that this is not the only strange artifact in her possession.

When pressed, she reveals that it all stems back to a

trip they took to Jamaica and a witch doctor they met there,

who brought a young girl back from the dead before their

very eyes, or at least that's how she remembers it. She's

been practicing witchcraft for years, she tells him – why

else did he think he was leading such a charmed life? Outraged

by his wife's devotion to such superstitious nonsense, Norman

destroys every last magical object, despite his wife's pleas.

"I will not be responsible for what happens to us if

you make me give up my protection!" she cries. There's

clearly more than career enhancement going on here.

Now if any or all of this sounds a little hokey then let

me assure you that it never plays that

way. Right from the start, director Sidney Hayers treats

the story as seriously as he would any straight drama and

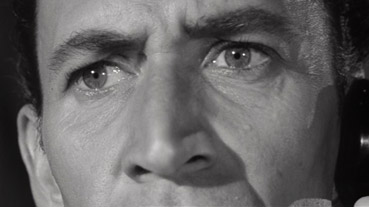

has clearly instructed the cast to do likewise. In a compelling

central performance, Peter Wyngarde completely sells Norman

as a no-nonsense, self-assured sceptic who is determined to confront

and combat superstition wherever he finds it, and his

battle of wills with his wife (the equally convincing Janet

Blair) is both tense and believable. In that reverse-belief

approach horror movie fans have to apply to their beloved

genre, you know that he's talking perfect sense, but also

that he's wrong. Watching it with my girlfriend I was amused

when she yelled at the screen, "Why do men never listen?"

No comment.

From this point on, Norman's good luck all but evaporates

in a nicely judged mix of earthly problems and possibly

supernatural forces. It's in the latter that the film really

flexes its cinematic muscle, especially in an excellent

sequence where the house comes under assualt from unseen forces, their power and malevolence suggested entirely through the use of lighting, camerawork and sound effects. It's a scene

that scared me witless when I first saw it years ago, and

even all these years later, with umpteen horror films under

my belt, it still sent

chills up my spine. There are plenty of shots suggesting

the form that this force takes – the real surprise is how

convincing it proves to be when we actually get

to see it.

This proves to be Night of the Eagle's trump card,

that it sucessfully sells its witchcraft as real and its consequences as genuinely

threatening. It's a rare trick managed only by a select

few – that two others are Night of the Demon

and The Devil Rides Out (1968) is only

appropriate, given that Night of the Eagle

bears a structural and visual resemblance to the former

(the similarity in title is surely no coincidence) and has

the latter's breathless, incident-packed pace. A tight,

intelligent script (co-written by genre maestro Richard

Matheson, who also wrote the screenplay for The Devil Rides Out), Wyngarde's performance and Hayers' assured handling

are all crucial here, with Norman's transformation from hardened

sceptic to desperate believer an object lesson in how to

make such a switch of belief convincing. Technically the

film outshines its doubtless limited budget via Reginald

Wyer's fine monochrome cinematography, Ralph Sheldon's fat-free

editing, and some startlingly good special effects – there's

a road crash here that's as alarming as any I've seen, despite being created largely through what I presume is back-projection.

I

have fond memories of my late night discovery of Night

of the Eagle many years ago, and though initially

excited by the news of the DVD release, I was worried that

it would not measure up to my recollection. I'm happy to

report that it did. It's a worthy first release (along with

the 1960 Circus

of Horrors, also directed by Sidney Hayers)

for Optimum's new Horror Classics collection, and will hopefully

reach a wider audience of horror fans who didn't realise

that, once upon a time, we British could also make classy,

intelligent genre films that would stand the test of time.

The

picture is framed 1.78:1 and although the IMDb carries 1.85:1

as the correct aspect ratio, which seems more likely, although 1.66:1 was also a popular aspect ratio of the time. Certainly the framing

here looks correct and never feels cropped in any direction.

Although not of Criterion-style sharpness, the anamorphic

transfer is nonetheless a very respectable job, with good

detail and a very nice contrast range. Blacks appear solid

throughout and dust spots are rare.

The

Dolby 2.0 mono track is clear and free of distortion, although

the dynamic range is obviously a little restricted due to

the film's age.

None.

This is a film-only disc, but that's reflected in the budget

price.

This

is a good month for classy 1960s British horror, with Redemption's

recent release of City

of the Dead now joined by two more fine but

little seen works, the first releases of a promising-looking new label

from Optimum. All three films are strong examples of their

craft and deserve a place in any self-respecting horror

fan's collection. But you don't have to be a genre devotee

to appreciate an intelligent, well made chiller, and if

that appeals, then Night of the Eagle certainly

fits the bill.

* My

sincere thanks to Pearce Duncan for pointing out this glaring

ommission in my original review.

|