| One

thing older horror movies seem to still have over their modern equivalent is that

they had better voices. From the classic monster movies of Universal

Studios through to the golden days of Hammer, horror films featured stars who made their names in

the genre and sometimes remained forever associated with

it. And they all had terrific, instantly recognisable voices,

from Bela Lugosi's Hungarian lilt and Boris Karloff's soft

English purr to the mischievous twang of Vincent Price and

authoritative baritone of Christopher Lee. Lee in particular

had and still has a commanding screen presence. His first

appearance as the Count in Terence Fisher's 1958 Dracula remains one of the best of all screen entrances, and he's one of the few

actors I instantly believed as Mycroft Holmes, a man reputed to be even

smarter than his famed brother Sherlock. He's someone I'd

still love to meet and sit with and talk to for a few hours –

I have no doubt it would be an enthralling and enlightening

experience. Lee could talk about anything and make it sound

interesting. His own life and work is a story in itself – check

out his fascinating autobiography Tall, Dark and Gruesome if evidence is required.

But

a quintessential element of Lee's voice is its Englishness,

a fact not affected by his ability to speak eight languages –

five of them fluently – and his subsequent early casting

in the odd ethnic role. And yet in John Moxey's 1960 City

of the Dead he plays an American professor. Now

some of you might be wondering why, when you have such a magnificent voice

at your disposal, you would saddle it with an American accent?

Indeed, why not cast an American actor in the first place?

Well in the case of this particular movie there are a couple

of very good reasons. First is that while the story is set

in America and thus required American characters, the film was

made by a British film company at Shepperton Studios in

London. And then there's a budget of allegedly just

£45,000, hardly enough to allow for the import of

even a small-scale American star. After The Curse

of Frankenstein and particularly Dracula,

Lee and his close friend and co-star in these films, Peter Cushing (another marvellous voice, of course), were the nearest thing the UK horror

industry had to bankable names. But Lee is also a fine, fine

actor, and no director worth his salt would pass up an opportunity

to work with him if the role suited, whatever the nationality

of the character.

The

story kicks off back in 1692 in the city of Whitewood, Massachusetts,

whose pious citizens are about to burn a woman named Elizabeth

Selwyn for witchcraft. On her way to the stake she appeals

to one of the gathered onlookers, Jethrow Keane (Valentine Dyall, yet another splendid voice), for help

and suspicion

momentarily falls on him. Has he been consorting with a

witch? He denies it and his word is apparently good enough,

so the execution proceeds. But as the pyre is ignited, Keane

begins mumbling appeals to Lucifer to save Selwyn from the

flames and the sky blackens. Before her consummation by

fire, Selwyn makes her pact with the Devil and angrily curses

the city and its inhabitants.

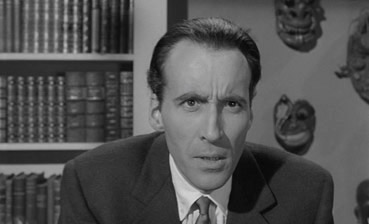

We then leap forward to modern times where this moment in history is being

recounted by professor Alan Driscoll (Christopher Lee) to

his students as part of a course in the history of witchcraft.

One of them, Nan Barlow (Venetia Stevenson), wants to research

her paper in more detail and asks Driscoll for a good place

to start. He suggests she visit Whitewood itself, now a

small, out-of-the-way village, and despite the protestations

of her scientifically minded brother Richard (Dennis Lotis)

and cynical boyfriend Bill (Tom Naylor), off to Whitewood

she heads.

Everything

about her approach to the village is unsettling. The

area is shrouded in thick fog, a gas station attendant she asks

for directions is surprised that anyone would actually want to

go to Whitewood, and a stranger she picks up on the way (whose

face should be familiar to the audience by this point) vanishes from her

car on their arrival. Whitewood itself offers little comfort for the inquisitive traveller.

There's Mrs. Newless (Patricia Jessel), the

frosty proprietor of the village inn, who initially claims

that there are no free rooms but on the mention of Professor

Driscoll's name suddenly discovers a vacancy. And there's

Lottie (Ann Beach), the constantly terrified and mute chambermaid,

who is scolded by Mrs. Newless when she tries to pass a

message to Nan. What might this girl know or be trying to

say? There's the sightless local priest, the Reverend Russell

(Norman Macowan), who barricades Nan's entrance to the church

and urges her to leave. And there are the citizens themselves,

who drift through the fog at night and stop to stare silently

at Nan as she passes. An ideal holiday destination this

clearly is not. The only friendly face she encounters is that of

the Reverend's granddaughter Patricia, the recently arrived

proprietor of a bookshop that I can't imagine has ever

had a single customer until Nan walks in. Even she can't afford

to buy the book she wants, a weighty tome on witchcraft

that she ends up borrowing and becomes so enraptured by

that she fails to spot the warnings it offers regarding her

own possible fate.

There

can't be many horror fans who will taken by surprise by much of the above. Modern day tales of witchcraft require characters

to be sceptical and walk blindly into situations that the audience

will recognise instantly as dangerous. As genre devotees we often

execute an about-face on belief when it comes to our engagement

with a movie – in the real world, if someone tells you that

a cup fell from a table because a ghost pushed it off youwould probably mock them, but if it happens in a genre film then of course it was a ghost, you silly sceptical fool. I've got a cellar

and a loft in my house and I'll happily go into either with just a lamp

to guide me, but the moment someone does likewise in a horror

movie, their daftness almost has me screaming at the screen. And so

it is with Whitewood. We've seen it before and we thus know

what's going to happen, but one strengths of City of the

Dead, especially for its time, is that it lulls you into

a false sense of certainty and then blindsides you. It's

a turn of events that warrants a comment or two, but also

one that should not be revealed to newcomers. And so...

Now

listen. If you are planning to see the film and don't want

to know how the plot unfolds, then I seriously suggest you

skip the next paragraph. Really. This discussion is for those

who know the film or its plot. Look, I'll make it easy for

you – just click here and the

page will scroll down past it.

Are we alone now? Good. Those

of you who are familiar with the way the film pans out will know that

over halfway in it throws a curve ball by unexpectedly killing off what we have come to assume is its central character, sacrificed by the Whitewood coven as

part of their ritual of everlasting life. The similarity

to the same but more widely celebrated carpet-pull

executed by Alfred Hitchcock in Psycho has been widely remarked on, but the parallels don't end

there. Blonde-haired Nan travels from home to an out-of-the-way

spot to stay at a dodgy hotel and is killed by the establishment's

proprietor. The disappearance is investigated by two men

and a woman, a group that includes a sibling and a boyfriend,

who are falsely informed by her killer that Nan departed

the day after she arrived. Two of them even approach a figure

at the end and get a shock and scream when it's face is

revealed. Wow, those co-incidences are piling up, aren't

they. The obvious supposition is that there is some serious

borrowing going on here and that the film is trading on

the success of Hitchcock's masterpiece. There's just one

thing: the two films were shot almost simultaneously in

different countries with little knowledge of the other's

existence, let alone content. Uncanny, huh?

OK, we're back on safe ground.

No more serious spoilers, I promise.

The

story provides the framework, but City of the Dead's

well-deserved status as a cult favourite lies in its execution,

notably John Blezard's creepily suggestive art direction

and Desmond Dickinson's extraordinary monochrome cinematography. Between them they make it feel almost as if

Nan has stepped out of the real world and into one created

from her own nightmares, as figures stand motionless in

thick fog or shuffle silhouetted into the graveyard for

a midnight mass. Even the flickering of firelight as

Nan first enters the inn has strangely demonic overtones, while her descent into the blackness of cellar below her room, guided

only by a narrow beam of light from her torch, is as tense as any

such scene in more recent horror cinema. The imagery and

atmosphere don't just belie the film's budget, they make

a mockery of it – rarely if ever have you seen a horror

film that looks or feels quite like this.

But

if Dickinson and Blezard give the film its distinctive visual

style then all credit to first-time feature director John

Moxey for knowing just what to do with it. His camera placement repeatedly intensifies Whitewood's creepiness,

from his arrangement of multiple characters in frame to

his thoughtful and effective use of personal viewpoints (Nan's arrival

is in town is made all the spookier by the motionless figure

distantly illuminated by the car's headlights), while his

inventive use of editing delivers a John Carpenter-esque

frisson when an eerie late night dance comes to the sort

of abrupt ending that only film can deliver.

The

cut-it-with-a-knife atmosphere is very effectively counterbalanced

by performances that have conviction but are also, for the

most part, nicely underplayed, no mean feat for a partly

English cast having to work with (mostly convincing) American

accents. Venetia Stevenson (whose accent is real) in particular

makes for a likeable and believable Nan, while Lee quietly

shines as the professor who may be more than he seems, and Patricia Jessel walks a fine line as the sinister Mrs. Newless,

nicely avoiding the sort of melodramatic interpretation

such a role almost invites. Only Tom Naylor as boyfriend

Bill Maitland seems to struggle a little, but he makes amends in

a strikingly visualised climax in the Whitewood graveyard.

The

first production by independent company Vulcan, who after

three films became Hammer's only real rival Amicus, City

of the Dead is a fine example of the sort of restrained,

imaginative and smartly made British horror film (Sidney

Hayers' 1962 Night

of the Eagle was another) that should have

led the way forward for the genre. But the ball was dropped

and picked up by the likes of Roman Polanski and George

Romero, whose 1968 Rosemary's Baby and Night of the Living Dead marked the end

of UK horror film dominance and the beginning of a new wave

that would put America back on top.

This

review looks at both the VCI US DVD and the new Redemption

UK 2-Disc Special Edition. Although the latter appears to

have been sourced from the former, there are a couple of

significant differences. I'm willing to concede that the

difference in extra features may be down to licensing issues,

but before we get to that there's an issue that I will accept

no excuse for.

Sourced

from a good quality print, the anamorphic 1.66:1 transfer

on the VCI disc is first rate. Initially it seems almost

as if pure blacks and whites are absent in favour of a rich

palette of grey tones, but once we get to modern night-time Whitewood

the contrast is bang on, with deep, solid blacks

and well rendered highlights that handsomely showcase Desmond

Dickinson's gorgeous cinematography. There are a few dust

spots, but you rarely even notice them, and the print is

otherwise clear and the detail impressively crisp. For a

low budget film of this vintage, this is an exceptionally

good job.

The

Redemption disc has been sourced from what looks like the

same digital master, but has undergone NTSC to PAL conversion

that causes blurring on movement and just takes the edge

of the contrast found on the VCI disc. But the real crime

committed here is that the widescreen transfer is letterboxed

rather than anamorphic, reducing the resolution

by a third.

Given the high quality of the anamorphic transfer on Redemption's Sacred Flesh DVD and the fact that VCI's transfer was mastered from a

35mm print owned by the British Film Institute, this is

both surprising and hugely disappointing.

The

2.0 mono soundtrack is the same on both releases – functional

and clean, with only a slight hiss to show it's age.

The

extra features on the Redemption disc are consigned to disc

2 (more on that later) and have largely been licensed from

the VCI original. Most of the extras on the VCI disc have

been included on the Redemption disc, but with two major

exceptions.

Commentary

by Actor Christopher Lee (VCI disc only)

Before you get too excited, a couple of irritating misjudgements have been

made by those recording and mixing the commentary that stops this from being

the killer track it should have been, and that's the decision

to sit Mr. Lee in front of a film he hasn't seen for over

40 years and shut off the soundtrack. Lee thus repeatedly

wonders out loud what is being said by the characters and

is bemused by actions that would be clear if he could hear

what they were saying. In an insult to injury move, the

soundtrack has been included for our benefit, and is occasionally

loud enough to compete with Lee for our attention. But

in other respects this is an enjoyable and very worthwhile

inclusion. Lee spends a little too much time describing

what we're watching, but moderator Jay Slater regularly

interrupts with questions that give rise to some fine stories

and interesting background detail on the filming.

Anecdotes abound and are not consigned to this film, his

work with the likes of Tim Burton, George C. Scott and even

George Lucas also getting a little coverage. There are some

engagingly humorous moments, not least when the subject

of Star Wars comes up and Slater specifies Attack of the Clones. "Yes, well..."

Lee begins in response to a title he was not impressed with,

"...you'll have to speak to George about that." He

also discusses the nature of good and evil in the modern

world, and suggests, contrary to popular opinion (but agreeing

with Camus in his review of Casino

Royale), that Timothy Dalton was the actor

best qualified to play James Bond. "Ian Fleming was

my cousin," he reminds us, "so I know what Bond

was supposed to be."

Commentary

by Director John Moxey (VCI disc only)

VCI's second coup is to convince John Moxey to come into the studio

to share some memories of the shoot, and although there

are quite a few long pauses early on, the track gets busier

as it progresses and proves an involving listen. There's

plenty of information on the actors and a fair amount on

the technical details, notably Dickenson's lighting and

photography – "Every first-time director should be

lucky enough to have such a great cinematographer work for

him," he remarks. He fills us in on the work he's done

since, and offers an opinion on some subsequent genre films,

some of which he likes – Night of the Living Dead, The Exorcist, Jaws, Rosemary's

Baby – but others he's less happy with – The

Shining, The Blair Witch Project, Friday the 13th, and just about anything that

throws gore at the screen. It's all good stuff, and adds

to the VCI disc's completist feel.

Interview

with Christopher Lee (45:07)

Lee is interviewed by fan-faced

genre critic Brad Stevens, who also supplies the noddies

to cover up the editing. With his work on City of

the Dead covered in the first commentary, Lee here

looks back at his career and the directors and actors he's

worked with, and gets seriously miffed at his continued

typecasting by the media. There's a little bit of rambling

and repetition at the end, but Lee is one of the most interesting

talkers out there, so I'm not complaining. One particular

note of interest is that the interview was conducted shortly

after the completion of Lord of the Rings but before its release – Lee predicts it's going to be huge.

Interview

with John Moxey (28:18)

The lively Moxey revisits some of the ground covered in

his commentary, but there's enough new stuff here to keep

this interesting, especially the details of his early career

and his subsequent work in America.

Interview

with Venetia Stevenson (19:50)

The actress recalls her role as Nan Barlow and suggests

that the main things she brought to it was an American accent.

She covers her career, including her abandonment of acting

to become a mother and later a production manager – the

work she is most proud of is Walter Hill's Southern

Comfort.

Original

Theatrical Trailer (1:31)

Includes the final shot of the film and giveaways, so don't

watch this first.

Photo

Gallery (VCI disc only – 3:23)

A rolling gallery of stills, behind-the-scenes photos and

promotional material.

Biographies (VCI disc only)

Slowly scrolling biographies and filmographies for John

Moxey, Venetia Stevenson, Christopher Lee, Patricia Jessel,

Dennis Lotis and Betta St. John. Dennis Lotis's biography

is spectacularly brief on detail.

Star

and Director Biographies (Redemption disc

only)

Not biographies but filmographies for Christopher Lee, Patricia

Jessel, Denis Lotis and John Moxey.

Promo

Art (Redemption disc only)

10 pages of promo material.

Stills (Redemption disc only)

7 stills, not that big.

A

memorable and very stylish British horror film that too

few appear to have seen. Well now's your chance. A 2-disc

Special Edition may sound like a fan's wet dream, but Redemption

has fumbled the ball here, a revamp of VCI's disc that

loses two of its best extra features and the anamorphic

transfer. This is particularly galling

given that the American release was mastered from a British

film print, only to be standards converted and downgraded

for the UK DVD release. And it's becoming an old gripe, but

how is it, exactly, that VCI can fit more onto one disc

that Redemption can on two?

|