| |

"Over the last 20 years, very few films have made a bigger impression on me than The Honeymoon Killers." |

| |

François Truffaut – Cahiers du Cinéma, October 1980 |

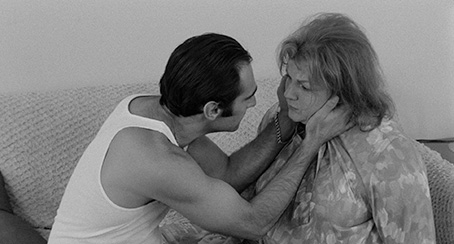

Martha (Shirley Stoler) is an overweight and surly head nurse who lives with her mother and is convinced that she'll never find the man of her dreams. When she discovers that her friend Bunny (Doris Roberts) has signed her up to a lonely hearts agency she's initially furious, but is eventually persuaded to give it a go. Imagine her surprise when she receives an encouraging letter from one Raymond Fernandez, a charming and sincere-sounding man of Spanish descent. The two correspond and eventually meet, by when Martha has fallen for this Latin charmer. They spend a few passionate days together, but after securing a monetary loan from Martha, Ray returns to his home in New York on the pretext of having to attend to business interests. What Martha fails to realise is that Ray is a serial seducer who romances and even marries lonely women in order to con them out of their money and possessions.

That, you might think, would be a solid enough set-up for an involving tale of love, loneliness and moral redemption, but we're just getting started here. After receiving a "Sorry dear, but..." goodbye letter from Ray, Martha enlists Bunny's help to call and convince him that she has attempted suicide as a result of his rejection. The concerned Ray responds by assuring Martha that he has not abandoned her and invites her to visit him in New York, where he elects to reveal the truth about his activities. The smitten Martha is not dissuaded, and after depositing her mother in a nursing home, she moves in with Ray, though insists on accompanying him on his future cons by posing as his sister. She has only one stipulation, that Ray does not sleep with any of his victims. It's a condition the unexpectedly love-struck Ray agrees to, but Martha's pathological jealousy soon creates problems for the pair.

It's an old adage of storytelling that characters don't have to be likeable to be interesting, but filmmakers still tend to hedge their bets and make sure that even flawed leading men and women stay on the safe side of sympathetic. It's rare for a film to push that boundary too far, to bond us with a character and then ask us to stay with them when they cross that almost invisible line that separates salvageable damaged goods from unredeemable evil. It was Vince Gilligan's willingness to dive head-first into this territory that made Breaking Bad such gripping, challenging and rewarding television – in the final series there were times when my character allegiance was switching on an almost scene-by-scene basis. And so it is with Martha. Her unflattering introduction casts her as an almost cartoonish matronly killjoy, as she angrily berates two of the junior hospital staff for bringing their tawdry romantic involvement into work. Yet once she's back home and writing hopeful letters to Ray I absolutely felt for her, particularly as we are tipped off at an early stage that our Ray is a heartless con-man and that this would-be romance is unlikely to end happily for his latest prey. But once she dumps her mother and moves in with the man she's been telling friends and family is her husband, it became harder for me to be sure exactly how I felt about our Martha, or indeed her new partner. Which is, of course, where things get really interesting. As with Breaking Bad, I found my allegiance repeatedly shifting. Thus appalled though I should be by the manner in which Ray misleads and manipulates the women he continues to scam, I began to be more frustrated by the ways in which the jealous and volatile Martha would repeatedly queer the deal for him. Rarely, if ever, did I spare a thought for his victims. This, I should point out, was destined to change, and how.

As Martha and Ray argue then reconcile to plan their next move, hovering in the background all the while is a title that signals where the drama will eventually head, underscored at the start by an opening caption that talks of the "unbelievably shocking drama" that you are about to see. But here's the thing. For all their flaws and frustrations, Martha and Ray have been very effectively established as the lead players in this story, and while the bond we form with them is morally problematic, it's as real as the one so many of us later formed with Walter White in the aforementioned Breaking Bad, and I make that association deliberately. Here's a question for those of you who know the series. Do you remember the point at which you felt that Walter first crossed a line from which there was seemingly no turning back? For me and for many it was when he inadvertently prompted Jesse's manipulative and overdosed-on-heroin girlfriend Jane to roll over onto her back in her sleep, then stood and watched as she choked to death on her own vomit. We'd earlier been given cause to really dislike Jane, but the gobsmacking coldness of Walt's inaction seemed to cross a moral boundary from which there was no return. Yet a couple of episodes later I was back in his corner. From this point on, however, my relationship with him as the series' antihero proved to be a complex and repeatedly challenging one.

In The Honeymoon Killers that crossover point – or should I say the first crossover point – comes after Ray accepts an offer of $4,000 to marry the pregnant Myrtle (Marilyn Chris), a woman who claims that she is finished with men and just wants Ray around as a token father figure when the child is born. Once they are wed, however, the sex-hungry Myrtle is all over Ray and quickly becomes frustrated by the presence of the interfering Martha. Furious with jealousy, Martha uses Ray to trick Myrtle into swallowing an overdose of pills, and when Myrtle falls ill, Ray bundles her onto a bus and leaves her there to die. It's right here that I had my first Walter White moment. Such is our peculiar bond with Martha and Ray that in spite of their behaviour, it's oddly easy to be frustrated by Myrtle's eager sexual advances to Ray and read them solely as potentially disruptive to his relationship with Martha. But as Myrtle sits on the bus, a weeping and vulnerable ball of pain and terror and seemingly aware of her own impending death, her lonely isolation and sense of complete abandonment is genuinely painful to watch. It's here that the cruelty of Ray's bullshit patois and the devastating impact of the couple's actions really hits home. They're no longer con artists, but destroyers of lives.

From here on in things get even more uncomfortable, with a pall cast over any woman unfortunate enough to get a positive response from Ray and an envious glance from Martha. This peaks in the film's only explicit on-screen murder, a tense and gut-wrenchingly unpleasant sequence whose impact is heightened by its unsensational handling, the wide-eyed terror of its middle-aged victim and the protracted and brutal nature of the murder itself. The final, traumatic double-murder that later follows should see the last vestige of audience empathy give way to horror, and yet there's still something perversely touching about the final coda, one that makes it clear that we have not been watching a serial killer movie but a twisted and unsentimental love story. And if you weren't already disturbed enough by what you've witnessed, try remembering that the film was based on a once-notorious true-life case and that the details of Martha and Ray's activities and the murders themselves are largely on the nose.

It's well known now that The Honeymoon Killers was originally set to be the second feature of a new, young director named Martin Scorsese, who was fired early on either for working too slowly, for failing to shoot the required coverage or for including visual ticks that fledgling producer Warren Steibel wasn't happy with, depending on which version of the story you go with. He was replaced by industrial filmmaker Donald Volkman but he also didn't last, and opera composer and first-time screenwriter Leonard Kastle was thus promoted to the director's chair. Surprisingly, there's no obvious stylistic discontinuity as a result; indeed, knowing that some of the footage was directed by Scorsese, there were shots I was willing to swear were down to him that it turned out were not. A key binding thread here was director of photography Oliver Wood (a cinematographer of some note whose later work includes the original Bourne trilogy and Die Hard 2), brought on board by Scorsese and later relied on for his visual acumen by the more actor-focussed Kastle. Stanley Warnow and Richard Brophy's editing also gives the film an edge and sometimes shines in its storytelling economy, as with the montage of correspondence between Martha and Ray that compresses weeks of relationship building into a purposeful minute of screen time, or the shot of Martha handing pills to Ray that cuts straight to Myrtle's subsequent bus seat suffering. And there are some bold and thoughtful directorial decisions here, the most memorable being the chilling decision to stay locked onto the terrified eyes of one paralysed victim as the unseen Martha and Ray can be heard on the soundtrack making hurried preparations for her execution.

More than once I've seen The Honeymoon Killers described as documentary-like, but I don't think that's quite right. The static shots and smooth camera movements of Wood's cinematography are stylistically more associated with drama than documentary, but he nonetheless creates a strong sense of realism by avoiding dramatic lighting and making regular use of practicals (lights that are part of the set being filmed). The decision to shoot in monochrome apparently arose out of Kastle's determination to strip the couple's actions of any glamour and had the added advantage of better low light capability, but it also creates that air of disturbing authenticity that helped to give 60s indies like Night of the Living Dead and The Sadist their still astonishing impact.

The Honeymoon Killers is an extraordinary one-off that has stood the test of time better than I could ever have expected. It's been some years since I first caught it and while I remember being startled by what I had seen, I struggled to recall specifics, though the image of Ray abandoning the dying Myrtle on the bus haunted me for years. Watching it again I was struck by how well made and performed a film this is. Brooklyn-born Tony Lo Biano – an actor whose subsequently busy film and TV filmography includes The French Connection, Homicide: Life on the Street and John Sayles' City of Hope – is utterly convincing as Latin Lothario Ray Fernandez, and while there may be just a whiff of theatricality about her judgemental workplace bossiness, once she's out of the uniform Shirley Stoler absolutely lives and breathes the role of Martha Beck. And let's give a shout for the supporting players: for Marilyn Chris' stomach-churning blend of pain and fear as the poisoned Myrtle; for Mary Jane Higby's wide-eyed terror as she backs away from a woman holding a hammer and a husband she realises she doesn't know at all; and for what Kip McArdle is able to do with just her eyes as she realises she is about to die and is powerless to stop it. By the halfway mark I was satisfied that the film was holding up well, but by the end I was once again left reeling, convinced all over again that this low-budget, small scale independent work was and still is one of the great American films of the late 1960s.

As a low-budget film shot on high speed monochrome stock, I once again was expecting to have to make allowances for the transfer here, particularly in the areas of sharpness and shadow detail, but this 4K restoration from the original camera negative surpassed all my expectations. The detail is perhaps not Hollywood mainstream sharp, but is still crisp enough to be able to read text on magazine covers and it frequently shines on clothing and textures (including faces), particularly when the light levels are good. The tonal range of the monochrome image is also very impressive, with allowances for variations dependant on the lighting, and black levels are bang on. Film grain is visible but less obvious than expected, and the image itself is spotless. This is far and away the best I've seen the film look. The framing is the original 1.85:1.

The Linear PCM mono track is free of damage and background hiss and crackle, but its narrow dynamic range and the harshness of the louder elements more readily betray the film's low budget origins. Given that this is likely how the original mix sounded, I have no complaints.

Optional English SDH subtitles are also available.

Love Letters (25:01)

A new featurette by Robert Fischer (who appears to be behind all of the newly shot special features here) in which actors Tony Lo Bianco and Marilyn Chris and editor Stan Warnow are interviewed about their work on the film. It gets off to a fine start with Lo Bianco enthusiastically assuring us that this remains one of his favourite film roles and that it's a film he is still proud of. That's what I like to hear. Chris reveals that she desperately wanted to play Martha and even faked up her weight for the audition, and when she was rumbled it was she who suggested Shirley Stoler for the part. Lo Bianco, meanwhile, explains how persistence and the ability to fake a Spanish accent got him past the initial rejection of him for the part of Ray. The story of Scorsese's arrival and departure is covered, and Warnow praises the teamwork between director Leonard Kastle and cinematographer Oliver Wood, and all three participants clearly still hold the film in high regard. An enthralling extra.

Folie à Deux (30:53)

Filmmaker Todd Robinson, the grandson of one of the investigating officers on the true-life case that inspired The Honeymoon Killers – also the inspiration for Robinson's own film Lonely Hearts (2006) – provides a welcome summary of the facts behind these film dramatizations. Illustrated with photos of Fernandez, Beck and a number of their victims, this is fascinating and educational stuff for those of us who've not researched the case ourselves (I'll admit I usually do, but this made the legwork involved largely unnecessary), and covers Ray and Martha's respective backgrounds, how they met and their subsequent crimes in some detail. This highlights the accuracy of the film's handling of some elements, but also its omissions and subtle alteration of facts. An essential companion to the film.

Body Shaming (6:08)

Todd Robinson re-appears to reveal that he only discovered that The Honeymoon Killers existed after he'd completed his screenplay for Lonely Hearts, though was clearly bowled over by what he saw. He touches on the very modern theme of body shaming, how Shirley Stoler was photographed in ways that exaggerated her size, and how the actor's discomfort at this actually worked for her character. He also pays brief tribute to Oliver Wood's monochrome cinematography and compares it to Conrad Hall's work on In Cold Blood.

Beyond Morality (9:05)

Belgian director Fabrice De Welz, whose 2014 film Alléluia was also based on the Fernandez-Beck case, offers his own appreciation of The Honeymoon Killers – which he describes as "a masterpiece" – and outlines how his film differs in its approach. His parting words are memorable: "Of course it's a terrible story. They killed people, they killed women, but there is a kind of beauty, in a way... or maybe I'm too fucked up, I don't know."

Theatrical Trailer (2:19)

"If you've never heard of Martha and Ray, see The Honeymoon Killers, then try to forget them." An interesting trailer, but with its share of spoilers if you don't know the case. Although clean of dust and damage, it's not in anything like as good shape as the main feature, which shows just how good this restoration is.

Booklet

There are two very worthwhile essays here. The first, by editor and author Johnny Mains, explores the true-life story of Ray Fernandez and Martha Beck in even more detail than Todd Robinson above, though there is inevitably some crossover between the two. I'd watch Robinson first and then come to Mains to have the story fleshed out. The second, by Michael Brooke, who was also producer of this disc and this booklet, provides a comprehensive overview of the various big and small screen adaptations of this story. Also included are credits for the film and details of the transfer.

I'm going to repeat myself here and restate that as far as I'm concerned, The Honeymoon Killers is one of the great American films of the late 1960s, and in its own small way is up there with Night of the Hunter as one of those unique films made by a first-time filmmaker who never again sat in the director's chain. Arrow have secured an excellent transfer for this dual format release, and backed it up with some very worthwhile extras. What more can I say? Highly recommended.

|