|

When it comes to classic-era kung-fu movies, most of us tend to think of Hong Kong, the home base of genre specialists The Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest. These are certainly the movies that I grew up on, blissfully unaware as I was back then that not only were exterior scenes in many of these movies shot in Taiwan, but Taiwan had its own martial arts directors, stars and movies. Distracted as I became subsequently by what world cinema had to offer, I remained ignorant of this fact until about 15 years ago, when I began revisiting some of the classic and lesser-known Hong Kong martial arts movies from that era as they were restored and released on DVD by companies like Hong Kong Legends. These discs would sometimes include commentary tracks, the cream of which were by Bey Logan, whose expertise on seemingly everything related to the making of these films proved to be eye-opening.

Stylistically, the Taiwanese films were on similar ground to their Hong Kong brethren, being largely historical pieces that were shot and edited to showcase the martial arts skills of the performers instead of hiding them in a blizzard of fast cuts and bemusing camera angles. Other signature elements will also be instantly recognisable to fans of first-wave Hong Kong martial arts cinema: the use of crash-zooms during a fight; the slight undercranking of the camera to speed the pace and give the action more impact; the audible wooshes that accompany every movement of an arm or leg in combat; the loud slaps and thunks of contact blows; the inevitable training sequence that transforms a novice into a martial arts master; and fights in which a villain can take a hundred blows to the head and body, but be brought down by a single deadly and often signature move.

In recent years, Eureka Entertainment has done a belting job of bringing restorations of first and second wave martial arts favourites to Blu-ray (too many of which I have failed to cover for the site due to misfortunes of timing and outside influences), but with Cinematic Vengeance they really have outdone themselves. This glorious box set includes eight films directed by Taiwanese martial arts specialist Joseph Kuo (full name Joseph Kuo Nan-hong) spread over four discs, each with a lively and hugely informative commentary by two experts in this field. For me, covering this was both a delight and a challenge, as with a commentary track on each film, this was the equivalent of 17 movies, as one of the titles is also presented in a significantly different alternative cut. That’s knocking on the door of 26 hours of viewing material, plus pauses and rewatching of scenes for accurate note-taking, and the time required to write it all up. I gave myself a week, one in which my daytime workload was lower than it has been of late. Inevitably, it took longer, sabotaged by my inability to plan efficiently around personal commitments and a sudden and unexpected surge in jobs that stripped away my lunchbreaks and ate into my early evening viewing time.

But here it finally is. I’d pledged before I started to keep the coverage of the individual films down to capsule review length, but collectively it’s still a bit of a monster. Logically, the reviews of the films themselves should be in chronological order, but I’ve gone with the order in which they were placed by Eureka on their review discs, which does see us dart backwards and forwards through the timeline of this period of Kuo’s career but was doubtless chosen by Eureka for a reason. Putting a final seal on this decision is that I wrote about each film shortly after watching it and before moving on to the next in this set, and as the reviews are peppered with first-time observations about recurring elements and references back to the films that precede it, shifting them into chronological order would have required quite a bit of rewriting, and I was already running late on this review.

One final note. In my reviews, I tend to identify the actors playing the roles by adding their name in brackets immediately after the first mention of the character that they play. One of the issues with these films is that sometimes it’s nigh-on impossible for those of us not blessed with an encyclopaedic knowledge of Thai martial arts cinema to nail this information down. The films’ IMDb pages sometimes list actors without assigning character names, and complicating matters further is that no two sources seem to agree on English spelling of the character names anyway. Thus, where no actor’s name has been cited it’s because I was unable to confirm who the role was played by. There’s also a good chance I’ve made a couple of errors, which I am happy to correct if notified of them.

And so, to the films.

| THE 7 GRANDMASTERS [JUE QUAN] (1977) |

|

Having been proclaimed by the Emperor as “He who holds up the Heavens,” ageing martial arts master Zheng Shang-guan (Jack Long) is about to retire when a note is delivered by flying dagger that questions his status as the Champion of the Jiangnan region. To secure his reputation, he sets out with his daughter Ming Zhu (Nancy Yen) and his three students, Yong Zhang (Mark Long), Tang Min (Li Hsiao-Fei) and Xiao Qi to challenge the seven provincial masters and prove that he is indeed the region’s greatest fighter. On their travels, they are approached by Shao Ying (Simon Li Yi-Min), an eager young novice who begs to be allowed to study under Zheng. When Zheng turns him down, he tags along anyway, ever hopeful that he might be taken on as a student.

And that, for a sizeable chunk of the running time, is the essence of the plot, which frankly will surprise no-one familiar with 70s kung fu movies, where the prime function of storylines was to move us swiftly from one fight to the next with the minimum of fuss. However, with martial arts cinema it’s all about the quality of the fights, and on that score The 7 Grandmasters is an absolute belter. They come thick and fast here, and I do mean fast – the first occurs before the five minute mark and the second a mere three minutes later. And they’re all superb, blistering displays of old-school martial arts performed at lightning speed and with machined precision by some of the fittest and most acrobatic performers then working in the genre. Yes, there are a couple of reversed shots to fake upward leaps and some brief instances of wire work to stage otherwise impossible moves, but for the most part we’re just watching highly skilled performers and ace fight choreographers at the absolute top of their game.

I’ve made the case before for comparing movie kung fu fighting to dance routines, and nowhere will you find a better example of this than in The 7 Grandmasters. Every move of every fight flows naturally into the next, while the lead players’ Peking Opera training enables them to smoothly integrate multiple handsprings and leaps into their routines. These battles are as awe-inspiring as they are thrilling, peaking in a brilliantly staged fight between Zheng and Grandmaster Sun Hong (played by stunt coordinator Corey Yuen) involving a range of weapons, including swords, poles, daggers and pikes. All are shot, directed and edited by filmmakers with an instinctive understanding of how best to showcase the skills of their performers, while a story that pits Zheng against seven Grandmasters, each with his own distinct fighting style, also keeps the combat varied and gives each of the fights its own identity. Thrown into the mix is Shao Ying’s inevitable journey from overeager novice to a fighter of considerable skill, one that involves taking beatings at the hands of the students assigned to train him, and the scenes we all know are coming when he gets to demonstrate just what he has learned.

There’s more than a whiff of Jackie Chan to the character of Shao Ying, who in the film’s first half is the film’s comedy foil, repeatedly trying and failing to impress Zheng and his students, eventually earning the master’s respect through his dogged refusal to be beaten down. There’s even a very Chan-like mix of comedy and action involving a battle of bodies and wits between him and Yong Zhang over a bowl of medicine that he has prepared for Zheng, one that sees the bowl change hands repeatedly, and often acrobatically, without its contents being spilled. There’s definitely a touch of The Seven Samurai to the group’s cross-country journey, with Yong Zhang’s hanger-on status having strong echoes of Kikuchiyo from Kurosawa’s film. Yet despite some late film narrative complications that see Yong Zhang bounced over to the dark side and back within a matter of minutes, The 7 Grandmasters really is all about the quality and frequency of its kung fu, and on that score alone it really is amongst the finest that the genre has to offer. And how could you not salute a film in which the young hero defeats his most fearsome enemy by kicking him with all the force he can muster in the testicles?

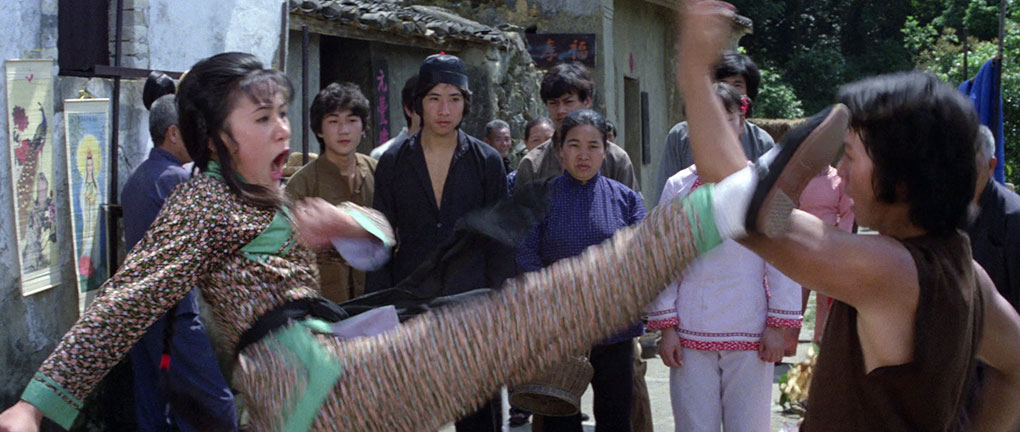

| THE 36 DEADLY STYLES [MI QUAN SAN SHI LIU ZHAO] (1982) |

|

The 1982 The 36 Deadly Styles gets off to a confusing start. It opens on the go, with two men named Wah-Jee (Nick Cheung Lik) and Uncle Wang being chased and attacked by four goons, the leader of whom – a red-nosed fellow referred to only as 4th Brother (Chan Lau) –could effortlessly qualify for the finals of an international gurning competition. We then switch scenes and are introduced to a long-haired master named Yuen Cheng Tien (Mark Long) as he informs his nephew, Lao Jing, that Kaung Wu-chun has escaped to Tibet. I’m sorry, who’s done what now? Lao Jing, who’s sporting a long grey wig that’s probably meant to be his real hair, announces his intention to assemble a team of four Devarajas and take care of him. Four what? Yan wonders if Lao Jing is up to the job and advises him to kill Wang and those who have escaped first. Wang, eh? Would that be Uncle Wang? Ah, I see, so… We then cut to another location where a man we later learn is named Huang (Yang Tse Lin) is running away from something, but stops when he is challenged by Lao Jing, who now appears to be named Jing-shi. Wait a minute, I’m getting confused. Huang protests that he wasn’t behind the killings (erm…), and the two men fight until Jing-shi lands a blow that leaves Huang clutching his chest in pain and fighting for breath. We then hop forward an unspecified amount of time and Huang is now a senior monk at a monastery, but is still suffering crippling chest pains from that devastating blow, something that he then has to struggle to mix up some medicine to treat. Just so you know, this involves skinning a snake, and I’m fairly sure we’re not talking about a prop animal here.

All of this unfolds over the course of a breathless ten minutes, and by the time we reach this point, I was completely lost and had to watch the whole thing again and pay really close attention to the subtitles. I still wasn’t sure how all of these half-sketched stories could be connected, at least until the exhausted Wang and Wah-jee show up at the monastery door begging for shelter and still being chased by 4th Brother and his men. Wait, how long have these guys been running? Was the last bit a flashback? My head hurts… Huang helps Wang to fight and ultimately kill the aggressors, and then has his student monks dump the bodies by the river, unaware that 4th Brother has faked his death and is then thus able to flee. The fight takes its toll on Wang and Wah-jee, but while Wah-jee is left seriously injured, the bloodied Wang dies of his wounds.

Where The 36 Deadly Styles loses out to its predecessor in this set (personal opinion alert) is in the decision to fill the gaps between its fights with comedy, and I use that term in its loosest sense. All comedy is a matter of personal taste, of course, but there are two comedic styles in particular that you’ll find often in classic era martial arts cinema. The first is the style that Jackie Chan honed to perfection, in which props, characters and the environment are used to transform a fight into an acrobatic slapstick sequence, which at its most inventive and energetic can take your breath away at the same time as it makes you laugh. The second is the sort that for my money doesn’t travel well at all, in which grown men behave like simpletons and fall victim to idiotic slapstick buffoonery that usually results in injury or indignity, which is wildly overacted and accompanied by cartoon music and sound effects. I’m sure there are genre fans aplenty who finds such crude japery hilarious, but for me it’s as funny as my hernia, and when sustained can every bit as wincingly painful. Unfortunately, a little too much of the comedy in The 36 Deadly Styles falls into that second category. The first warning signs arrive in the shape of novice monks who are clearly too stupid to wash their own feet, let alone grasp a range of theological concepts. But the most discussed and eye-widening humdinger arrives in the shape of the preposterous wigs worn by the bad guys, the most absurd of which adorns the henchman played by Yang Szu, aka Bolo Yeung, who was so memorable as heavily muscled henchman Bolo in Enter the Dragon but here looks intermittently like Jordan Peel dressed up for a comedy drag sketch.

The saving grace, as expected, are the fight sequences, and while not in the league of those in the previous film – the ones there played like real fights, whereas these have more of the feel of exhibition matches – they are still inventively choreographed and performed with appropriate and enjoyable gusto. The medicine bowl battle from The 7 Grandmasters is neatly reworked here with a bowl of rice, and how refreshing it is to see Jeanie Chang, who has a somewhat thankless role in the earlier The World of the Drunken Master (see below), ably demonstrating that it’s not just the guys who get to show what they can do with their fists and feet. In common with the Jackie Chan movies that were doubtless its inspiration, the comedy takes a welcome back seat in the later stages, and the action builds to a briskly performed and well shot climactic fight involving multiple opponents on each side, before narrowing down to the inevitable one-one-one battle.

As a side note, the film also shares with its Hong Kong equivalent a cheerful disregard for music copyright, and is more blatant than any other film in this set in its pilfering. This is signalled up front by a psychedelic title sequence set to Jerry Goldsmith’s main theme for the 1967 western Hour of the Gun, but the biggest surprise comes when the injured 4th Brother sits down to write a letter asking for assistance, and his thoughtful expression is accompanied by Henry Mancini’s now iconic main theme for The Pink Panther.

| WORLD OF DRUNKEN MASTER [JIU XIAN SHI BA DIE] (1979) |

|

After two films featuring characters that have more than a whiff of Jackie Chan about them, director Kuo comes clean with one that directly trades on one of Chan’s breakthrough hits, the previous year’s The Drunken Master, and it’s not just the title that he’s borrowing from here. Indeed, the film opens with a demonstration of the fighting style of the title by Yuen Siu-Tin, reprising his role as Drunken Kung-Fu master Beggar So from Chan’s film and its equally successful predecessor, Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow. Soak it up while you can, as once the title sequence kicks off, Yuen disappears to be replaced by Sung Hsi Yu as this film’s Beggar So. Or at least one of them. All will become clear. Anyway, before we meet the replacement So, we’re introduced to the similarly aged Fan Ta-Pei (Jack Long, who here looks like an older version the character he played in The 7 Grandmasters), whose countryside drinking is disrupted by the arrival of Chang Wuji (Wang Yung-Sheng), who has sought Fan out in order to test his skills against the 18 Moves of the Drunken Immortals. No sooner has Fan won the match than a messenger arrives with a letter inviting him to a small hilltop drinking establishment, where he is soon joined by the aforementioned Beggar So. After a quick fight that’s ended by the smell of premium wine, the two recognise each other, and over a drink they cast their minds back to their younger days, and it’s in this earlier timeframe that the majority of the subsequent film takes place.

Here Fan is still played by Jack Long, who despite some rather convincing old man makeup was only in his late 20s or early 30s at the time of shooting (his actual birth date is hard to pin down), while the young So is played by Li Yi-Min, who also had a prominent role in The 7 Grandmasters. Almost everything about how the film unfolds within this timeframe is influenced by Jackie Chan’s two breakthrough movies, from its deft mix of comedy and action to the journey the two men take from unskilled thieves to dedicated fighters of considerable skill. Li even sports a haircut that looks as if it was modelled on Chan’s own, and there seems little doubt that in an ideal world, one of these two roles would have been played by Chan himself. Which is not to take anything away from Long and Li, both of whom are on very fine form here and whose on-screen chemistry and early roughish amateurism makes them easily likable figures.

In other respects, the story plays it by the book, with Fan and So forced to work off the debt that their thievery has incurred by jobbing for vinery foreman Chan Qi (Chen Hui-Lou). He’s the one who teaches them drunken kung-fu (and yes, there’s a comical training sequence) after they take a beating from the inevitable bad guys, whose boss is played by Lung Fei, a genre veteran who also play the fanged samurai in One Armed Boxer. Possible love interest arrives in the shape of the vinery owner’s daughter, Lu-Yu, a role in which Jeanie Chang gets none of the action scenes she has in The 36 Deadly Styles and instead is consigned largely to scolding Fan and So and crying.

Considering my negative response to the overplayed buffoonery of The 36 Deadly Styles, I was genuinely surprise by how much more effectively judged and integrated into the action the comedy is here. For a start, there’s no wild mugging, no Loony Tunes sound effects or music cues (well, there is one), and a couple of the gags – a perfectly timed post-fight cut to the sorely injured pair, and a sequence in which they’re still practising moves in their sleep – are genuinely (and unexpectedly) laugh-out-loud funny. They also take their cue from Chan in a tightly choregraphed and staged battle over a bottle of their master’s premium wine, and another in which they fight over a piece of corn-bread, which is the one sequence that climaxes in a cartoonishly mocking music cue.

The fights increase in frequency and ferocity, building to a final third in which the comedy is dropped and the action barely pauses for breath, showcasing a string of battles with different numbers of combatants, some of which are almost the equal of those in The 7 Grandmasters. Once again, the killing blow of one fight is a crushing punch to the balls, which every male reader here knows full well would do the job, and even when this almost film-long flashback ends, we still have two fights remaining, one of which seemingly comes completely out of nowhere. There’s even a moment of sombre reflection that is so well handled that I was actually moved. Sure, as a whole it may not be the equal of Drunken Master or especially its official sequel, Drunken Master 2, but for what was essentially a low-budget cash-in, it sometimes comes surprisingly and impressively close.

| THE OLD MASTER [SHI FU CHU MA] (1979) |

|

“Nobody sets out to make a bad movie,” observes Mike Leeder tellingly on the commentary track for this peculiar 1979 misfire. It plays to a formula that had already been road-tested by favourite inspiration Jackie Chan four years previously in Rumble in the Bronx, one that has a Chinese martial arts master travel to America to visit friends or family and end up having to intervene in a battle with local hoodlums. Here, 74-year-old Grandmaster Wan (Yu Jim-Yuen), flies to Los Angeles at the request of former student turned martial arts teacher, Mr. Ding, who claims he needs his help because some newcomers to his gym are making trouble. This, however, is all a ruse on Ding’s part, as he is in serious debt to a Triad moneylender, a debt he plans to clear by betting heavily on Wan as he steers him into fights that on the surface he looks too old to win. Unhappy about this deception is new student, Bill (Bill Louie), who is working at the school to pay for his tuition, and he eventually tells what he knows to Wan, by when Ding has made more than enough to pay off his debt. An angry Wan turns his back on his former pupil, but decides to stay in the city for a while, moving in with Bill and getting a job at the hotel in which the young man works as a handyman. Want to guess what an inspiring martial artist like Bill might want from Grandmaster Wan in return?

That the setup is a little dopey – would an ageing grandmaster really travel halfway round the world to help one of his least successful students deal with a few ruffians? – is not really an issue in a genre in which plotlines rarely stand up to close inspection. That, it turns out, is the least of the problems here. First we have the pacing, with sequences drawn out beyond their functional length to take a tourist’s or cultural historian’s eye view of Los Angeles and American trends of the late 1970s. Thus a drive from the airport to a spot where Wan will be ambushed by young goons lasts for what feels like an age without telling us anything, and the story is effectively put on hold for almost 10 minutes while The Old Master hits the dance floor as a low rent Saturday Night Fever. The then newly popular activity of jogging leads Bill and Wan to a limp moment of cod-Rocky triumph atop a flight of steps, and the walls of Bill’s apartment are adorned with posters to remind us of the year in with the film is set, which is emphasised further by Bill’s moustache, mullet and fashions.

Then there’s Grandmaster Wan himself. There’s an air of stunt casting in the decision to have him played by Yu Jim-Yuen, the famed Peking Opera teacher whose students included Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, Yuen Biao, Yuen Qiu, Yuen Wah, and Corey Yuen. Wow. A great teacher he clearly was, but an actor and martial artist he wasn’t, and he was in his 70s when he made The Old Master, and is thus heavily doubled in every fight by a taller, younger and more agile performer. This itself would not normally be a problem (listen to all of the commentaries in this set and you might be surprised how common this practice was), but you quickly realise why Wan always wears a hat when fighting, and why he’s always filmed facing away from the camera or in silhouette. The substitution is so blatantly obvious that the illusion is effectively shattered and the fakery exposed, reminding you not just that you’re watching a movie, but cluing you in to exactly how it was made. Even the cinematography is peppered with peculiar quirks, from the occasional oddly slanted camera to shots where the focus is clearly off. I’m not even sure where to start with the ‘she’s large and amorous so she’s automatically funny’ American woman who takes a mysterious shine to Wan, and whose overplayed giggling and fake shyness play like something from a silent-era comedy.

So is it all bad? By no means. Bill Louie may not have the looks or charisma of the genre star he unsurprisingly never became, but he can certainly fight, even if he is (convincingly) doubled in the inevitable training sequence and insists on practicing a silly, self-created fighting style known as Robot Kung Fu. He’s at his best when pitched against a terrific young American fighter whose name no-one in the special features seems to know, and when these two go at it in an extended rooftop battle, the film takes a serious quality jump, at least until the Robot Kung Fu makes an unwelcome return. As is pointed out in the commentary, this should have been the final fight in a film that climaxes instead in a more ramshackle bundle in which Wan, Bill and some of Ding’s students take on the goons who have been giving them so much trouble.

Clearly made on a shoestring, and probably in a hurry, The Old Master is of interest as a late 70s Californian time capsule and for providing Yu Jim-Yuen with one of his only two film roles (the first was in the 1968 Jin dao guai ke). The best martial arts work is impressive, but you’ll have to wade through a lot of unexciting filler and too-obvious fakery to get to the good stuff. For me, this is unquestionably the weakest film in this set.

| SHAOLIN KUNG FU [SHAO LIN GONG FU] (1974) |

|

Or, more correctly as written on the title sequence of the film, Shao Lin Kung Fu, but ‘Shaolin’ as a single word is how it appears on the disc menu, on the film’s IMDb page, and just about everywhere else I’ve looked, so we’ll stick with that for now. Either way, it represents a serious quality leap over the previous film in this set, and it breaks with tradition by making the story feel more significant than the lightweight fight link it so often tends to be. Indeed, Shaolin Kung Fu – in which there is precious little Shaolin Kung Fu, it has to be said – so effectively balances the drama and the action that you’d almost think it was the work of a different filmmaker. Which, as it happens, it may well have been. Although included in this Joseph Kuo set and credited as his work on all of the usual sites, on this print of the film, the name of the director is Liu Shou-hua, who only has two other directing credits on IMDb and about whom I know nothing. Whether it was he or Kuo in the director’s chair is a question that’s debated in some detail by Mike Leeder and Arne Venema on the commentary track, with Venama convinced that Kuo did not direct this one and likely had a more supervisory role instead. Either way, Shaolin Kung Fu turns out to be one of the strongest films in this set.

After the (then) modern-day shenanigans of The Old Master, we’re back in past times in a town in which the Ren De rickshaw company run by Mr. Luo is losing business to the newly arrived Dong Yang firm run by Cao Jiabin, primarily because of the Dong Yang boys’ aggressive and bullying tactics. Unhappy with these antics is rickshaw driver Ling Feng (Wen Chiang-Lung), a formidable martial artist who has promised his blind wife Shiao-yuan (Yee Hung) that he will never fight again. If any of this sounds at all familiar, that’s because it’s a variant on the setup of The Big Boss, the film that catapulted a certain Bruce Lee to stardom, and as it was with the initially stand-back-and-watch Lee in that film, you just know that sooner or later Lin Fung is going to be given good reason to break that promise and kick the living crap out of an offending party. When it happens, the rules of martial arts movies ensure his actions are fully justified, and they certainly are here (the bad guy was slapping a child egg-seller around and stealing his wares), but Shiao-yuan is still hugely disappointed in him, having already been upset by the news that he has secured a well-paying regular customer in the shape of attractive courtesan, Miss Bai. Just as well she doesn’t know how fond Luo’s daughter Xiao Ling also seems to be of her husband.

As it turns out, Shiao-yuan has a good reason for her aversion to physical violence, but that doesn’t prevent Chu Tien-Hai (Cheng Peng), the slimy son of Cao Jiabin’s second-in-command, Master Chu (Yi Yuan), from coming to their house to settle the score with Lin, and on finding him not home, violently attempting to rape Shiao-yuan. When Lin returns midway through this assault, he completely loses his shit, and despite his wife’s pleas for him to stop, he beats Chu Tien-Hai to within an inch of his life. Then something unexpected happens. Instead of Chu Tien-Hai dusting off his bruises and plotting further revenge, we’re treated to a scene in which he is shown lying in bed and dying of his injuries as his distraught father tries to comfort him, only to then watch his son expire in front of his eyes. It feels almost like a serious take on that sequence in Austin Powers where we’re reminded that even the henchman of an evil mastermind had family and friends, and it takes a little of the sheen off of Ling’s hero status. This, of course, ups the ante considerably, and in his furious, eye-for-an-eye response, Chu provides Ling with plenty of justification for his future actions, ones that have their own serious consequences for him and those close to him.

The fights are once again smartly choreographed and performed with skill and gusto, and while not quite the showcase battles that pepper The 7 Grandmasters, the balance of action and storytelling here is definitely stronger. The attention paid to narrative and flow also makes if feel as if the fighting is a consequence of story development rather than the film’s raison d’être, and as a result I felt more invested in the characters and their fate, and was genuinely caught out by a couple of unexpected fatalities. Having recognised those early echoes of The Big Boss (a similar observation is made on the commentary), I’d also argue that Yojimbo casts its shadow on a mid-section capture, beating and slow recovery (director Kuo was apparently a huge Kurosawa fan), and Enter the Dragon also casts a shadow on a climax that pits Ling against an older martial arts master, who uses bladed weapons to inflict cuts on Ling’s shirtless torso.

Whoever was in the director’s chair was clearly on form here, with some choice exterior locations chosen for fights that are shot with some style, from the extreme wides used to emphasise the precarious height or eye-catching geographical features of the improvised arenas, to the handheld work that energises the pace and puts us in the midst of the action. There are no star-making turns here, but Wen Chiang-Lung makes for a likable and pleasingly fallible lead, and while the villains really are a nasty bunch, they’re not cartoonishly overplayed. Although the fifth film in this set, Shaolin Kung Fu is the oldest, and is technically part of that first wave of martial arts films that so seduced me as an teen. It’s exactly the sort of movie I would have lied about my age to see had it played at my local cinema, and one that many years later is still exciting, involving and well-crafted enough to seriously impress.

| THE SHAOLIN KIDS [SHAO LIN XIAO ZI] (1975) |

|

While we’re on the subject of misleading titles, it’s worth stating up front that there are no kids in this movie, unless it’s that generation gap thing that once saw older people referring to anyone under the age of 30 as “you kids today.” On top of that, for the first fifteen minutes or so you’d be forgiven for thinking that this is not a martial arts movie at all but a historical drama, which in a sense it is, albeit one in which characters intermittently do battle with fists, feet, swords, poles and other assorted and exotic weaponry. Like the earlier Shaolin Kung Fu, it’s not just a collection of impressively staged fights strung together by a threadbare plot, but a film whose action is driven by its story and characters. And oh boy, does one element of that have an unexpectedly contemporary ring.

Set in an unspecified period of ancient China, it begins with prime minster Hu Weiyong (Yuan Yi) being balled out by Emperor Zhu (Ko Shen Ting) because his son Hu Cai (Nan Chiang) has publicly killed two civilians. The Emperor orders Hu to sentence his boy to death, but in the very next scene, Hu Cai is seen riding through the centre of town at the sort of speed that suggests he’s been allowed by his dad to run free. He’s recognised by pharmacist Mr. Fan and known by his reputation by Miss Liu (Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kuan), who’s collecting medicine for her under-the-weather father, Liu Bowen (Chiu Chen).

That evening, Bowen is playing chess with his good friend Daoyuan and reveals that he’s expecting a visit from Hu, to which Douyuan reacts negatively, smartly talking his leave when Hu’s arrival is announced. When Miss Liu questions why he’s leaving by the side door, he responds, “To avoid meeting someone despicable.” Turns out he’s not wrong, as the purpose of Hu’s visit is to introduce Bowen to Qi Renhe (Heng Yu), an apparently famous doctor who prescribes a medicine for Bowen’s illness, medicine that turns out to be a poison that kills him in the night. Informed by her dying father of this treachery, Miss Liu sets out to seek revenge for his murder. To this end, she forms an alliance with Daoyuan and loyalists General Lu Qiyan (Peng Tien) and his son Shang Kuan (Carter Wong), who reason that with Liu Bowen now dead, traitor Hu will make a move to overthrow the Emperor. I should note that at this point we’re only 13 minutes into the film, and there are still a few more key players I’ve not mentioned, including Hu’s personal bodyguards Liu Yubao (Huang Fei-Lung, I think) and Wei Wenjin (Cliff Lok, also one of the film’s action directors), a deadly duo known as the Light and Dark Killers.

By the standard set by The 7 Grandmasters, the martial arts action is relatively slow in coming, and the first fight doesn’t feature any of the male leads, but is instead an act of righteous fury on the part of Miss Liu, who takes on and defeats eight sword-wielding soldiers with two daggers and far more energy than I had in my prime. Indeed, if the film belongs to anyone, it’s Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kuan, who as Miss Liu combines a down-to-earth beauty with a potent sense of danger that makes her a most credible and entertaining threat. It’s also she who is at the centre of a scene that I’ve come to realise is a genre trope that bats no eyelids on home turf but that will likely bemuse most newcomers to the genre. After dispatching a prison guard in a woodland setting straight out of a Hammer horror movie, she dons his clothes and masquerades as his replacement. The guard standing just opposite her questions whether she is new to the job, but at no point does he realise that she is not a man. And yet it’s in this scene that she is at her most beguiling, as she widens her eyes in almost comically quizzical fashion at the confused soldier. She’s clearly a woman, but in the world of the film she is unquestionably accepted for the man she is disguised as – apparently, if you are wearing men’s clothes in a martial arts movie, it renders people who might fall at your feet if you were wearing a dress oblivious to your looks and your tone of voice.

The story that unfolds, one ultimately centred around two scrolls of importance to both sides of the conflict, is certainly more robust than the genre standard, and the combination of this and the occasional wuxia style acrobatics leaps prompts commentators Mike Leeder and Arne Venema to question whether the film should be categorised as a kung-fu film or a political drama with action scenes. I lean towards the latter, but that’s not meant as a criticism of a film whose drama is involving, whose pace is often breathless and whose action scenes are blistering staged. And watching the film at a time when a litany of political scandals are unfolding in my home country, I couldn’t help but see parallels in a the story that is instigated by the actions of a deeply corrupt prime minister looking to increase his power by doing dodgy deals and betraying his people. When and where was this set again?

| THE 18 BRONZEMEN [SHAO LIN SI SHI TONG REN] (1976) |

|

In the days of Qing Dynasty China, the main opposition came from those still loyal to the deposed Ming Dynasty, and one location in which those fleeing Qing oppression could find sanctuary was the famed Shaolin Temple, in which young men could train to become the finest practitioners of martial arts in the land. As The 18 Bronzemen begins, the Qing Emperor issues a degree that the families of anyone who aligns themselves with the Ming rebellion be captured and sentenced to death. When the family of rebel General Guan Zhiyuan is targeted, they make the protection of infant child Guan Long their prime objective, and flee to a mountain hideout under the protection of an old friend, who over the next five years begins training the young Long and strengthening his body. When the hideout is discovered and Qing soldiers attack, Long is transported to the Shaolin Temple by his grandmother, Lady Shang (Lu Bih-Yun), and placed in the care of the Shaolin monks. Over the course of the twenty years that follow, Long (Peng Tien) is trained in Shaolin martial arts, a journey on which he is assisted by no-nonsense trainee monk Tiejun (Carter Wong). Before the two men can leave, however, they have to face a tough final challenge known as the 18 Bronzemen.

It’s worth knowing up front that all of the pre-Shaolin events unfold in the course of a furiously busy opening ten minutes, while Long and Teijun’s training at the temple and their testing at the hands of the Bronzemen occupies the next 50 minutes of the film. That’s almost the first two-thirds of the running time devoted solely to martial arts training and testing. To the uninitiated, that may sound like something of a slog, but it’s worth remembering that the 1978 Hong Kong martial arts movie, The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, kept its lead character in such training for a staggering 77 minutes of its 111 minute running time, and that film is of the undisputed greats of the genre. Here, the training and challenges that the students are subjected to vary in difficulty and are just occasionally questionable – one that requires the student to sit inside a giant bell as it is rung to test their fortitude would seem instead to be a guaranteed way of inflicting permanent deafness or lifelong tinnitus, and even within the film induces worrying nosebleeds. Other more energetic tests require the students to dodge flying darts and arrows and battle the armed or heavily armoured Bronzemen, and the final test involves lifting a red-hot cauldron in a way that burns a Shaolin symbol onto your forearms, a signature image from the TV series Kung Fu. I’m still not sure about the exact nature of the Bronzemen, some of whom have the appearance of armour-plated robots, while others are more obviously just monks who have been sprayed with gold paint, yet every hit landed on their bodies or heads is accompanied by a metallic clang. In the end it matters not, as they do offer a most credible challenge for those looking to take this final test and become a true Shaolin Master.

It’s after Long and Teijun leave the temple that what all this has been building to kicks off, and they’ve not been on the road for long before a certain genre trope from the previous film in this set makes a reappearance with the very same actor. Yes, Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kuan is back and disguised as a man, and everyone accepts her for who she claims to be despite her captivating looks and distinctly high-toned female voice. Quite why she’s behaving like such an arrogant arse is never made clear, but after attempting to provoke Long into a fight, she intervenes when a Qing assassin tries to kill him, and it’s during this fight that her true identity and her chance connection to Long is revealed. The three then join forces with one task in mind, to avenge the death of Long’s father by finding and killing his murderer, Hei Chuying (Yuan Yi).

I’m not in a position to comment on whether The 18 Bronzemen was the inspiration for The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, but like the later film, it turns the potential handicap of devoting so much of the running time to its training scenes to its advantage by making these sequences so enjoyable to watch. The Bronzemen challenges in particular involve some smart fight choreography and furious action, all of which is covered with aplomb by Kuo’s smart camera placement and Huang Chiu-Kuei’s sharp editing. I’ll also give the film points for having Long not succeed on his first attempt to pass the Bronzemen challenges, which emphasises their difficulty and allows director Kuo to stage a wider variety of tests. It all builds to a final three-on-one fight whose conclusion includes a blow that crushes what even on a freeze-frame I have trouble identifying as the exposed genitalia I presume it’s meant to be. Frankly, it looks more like the hit that precedes it has forced the victim’s intestines to fall out of his rectum. On the whole, another hugely impressive entry into this collection, but it turns out that there is an even better version…

| THE 18 BRONZEMEN – THE ALTERNATIVE CUT (1976) |

|

For the film’s Japanese release, director Kuo made some significant changes to the version initially shown in Hong Kong, which over time has been effectively lost and replaced by the Japanese cut, which is the version that was restored for this release and is discussed above. But while the original elements for much of the Hong Kong original edit no longer exist, in a move I both welcome and was genuinely excited by, that original cut has been reconstructed from a range of materials by Brandon Bentley and included on this disc.

Watching the Hong Kong edit after the Japanese recut reveals just how drastically those alterations impacted on the structure and storytelling flow of the film. A textual introduction on the disc menu sets the scene, but further clarification is provided in the commentary by John Charles, who appears to have an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of how the Japanese cut was constructed. Due to having to be sourced from a variety of media, from 35mm film to VHS tape, the quality of image in this reconstruction does vary quite a bit, but all of it is watchable, even if a couple of scenes have been sourced from a pan-and-scan 1.37:1 crop, which results in occasional aspect ratio changes. This should pose no problems at a time which such switches have been deliberately incorporated into films as diverse as The Pillow Book and The Grand Budapest Hotel.

The first major change is that the Hong Kong version opens with the infant Long being handed to the Shaolin monks by Lady Shang, a scene that runs for longer than the recut equivalent. The raid on the Guan residence that comes at the start of the Japanese cut comes later here as a flashback, and frankly it makes far more sense there, being a visualisation of the contents a final letter given to Long written by his dying father in his own blood. With no such flashback in the Japanese cut, Long is handed the letter, gives it a quick look and then puts it aside, which suggests he didn’t even take the time to read his father’s dying words. Even before I’d seen the Hong Kong version I thought this played oddly, and now I know why. We’re also informed in the commentary that segments of the first ten minutes of the Japanese cut were repurposed from Kuo’s next feature, The Blazing Temple (1976), and what would later become The Unbeaten 28 (1980), which helps explain why the young Long is played by two very different-looking actors in that version.

Perhaps the most significant change involves the character of Miss Lu, played by Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kuan. In the Japanese cut, she and Long meet by chance, and their second encounter in a tea house in a different town is played like an unfortunate coincidence. In the original cut, her unwillingness to let her argument with Long drop sees her follow him and Teijun on their travels, leaping onto a ferry boat with them (which is completely cut around in the Japanese version) and repeatedly taunting Long as he walks. Her appearance in the teahouse here thus makes so much more sense, playing not as a coincidence but as an “oh, will she never give up on this?” moment. It also turns out that even their first meeting was not a coincidental one (though this does raise a couple of questions that the film provides no answers for), which more neatly aligns with a revelation made by Teijun in the film’s finale. There are plenty of small additions and extensions to existing scenes, and this cut has a far better flow and a clearer, more complete and more satisfying narrative. For my money it elevates a damned fine film into a terrific one.

| RETURN OF THE 18 BRONZEMEN [YONG ZHENG DA PO SHI BA TONG REN] (1976) |

|

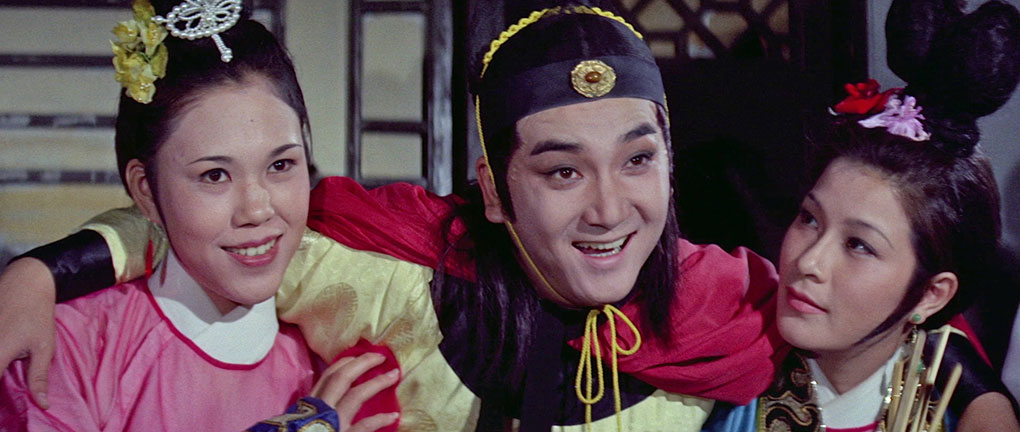

Return of the 18 Bronzemen is not the sequel that the title suggests but an intriguing alternative take of the same basic setup of The 18 Bronzemen. We’re once again in Qing Dynasty China, where the Ming rebels are causing problems for the country’s rulers. Once again, the story is built around one man’s lengthy martial arts training at the Shaolin Temple and his repeated attempts to beat the 18 Bronzemen of the title, but the difference here is that the individual in question is not the hero but the film’s nominal bad guy, Qing Emperor Aisin Gioro Yinzhi (Carter Wong). A Qing Emperor as a student in Ming-loyal Shaolin Temple you say? Well, not quite...

After cheating his way to power through a sneaky alteration made to his father’s will and receiving news that the Shaolin monks intend to rebel, Yinzhi looks back at a time when he donned everyday clothing and left the palace with a band of loyal bodyguards to move amongst his subjects without betraying his princely identity. In the third instance in a row of a certain trope involving a certain actor, the group stop at a restaurant and the bodyguards become curious about a lone diner at a nearby table, and wouldn’t you know it, it’s Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kuan dressed as a man again. It’s something that these goons accept at face value, which is why they then provoke her into a fight that they inevitably lose. Polly beats them all, but has a bigger challenge on her hands when Yinzhi steps in, starting a fight that then moves into the open air and is only brought to a half by the musings of a monk who wanders into the scene. A short while later, Yinzhi and his boys break up a robbery attempt and save a family (see, he’s not all bad), and Yinzhi is immediately taken with the family’s attractive daughter, and even drops into her garden the next day after jealously mistaking her brother for her lover. He fights the brother anyway under the guise of wanting to learn some of the boy’s nifty kung fu, but it gets a little out of hand and Yinzhi is forced to back off when one of his men realises that the boy is a student of Shaolin and thus impossible to beat. Yinzhi promptly decides that he too must become a Shaolin disciple in order to reach a similar level of skill. He thus approaches the Shaolin temple using what only just counts as an alias, and is initially turned away because of his age. His refusal to budge from the temple door for days, whatever the weather (a scene that has echoes in a later recruitment test in Fight Club), so impresses the monks, however, that they make a special exception for this determined man.

It was a ballsy move on the part of the filmmakers to make Yinzhi not only the central character but also the key point of audience identification. As the ruler of the enemies of the Shaolin Temple, he’s the bad guy by default, but he also cheats his way to power, then immediately tries to have his bother and rightful heir executed. Yet for the majority of the running time, we’re asked to bond with him and feel for his struggle, as he genuinely commits to his training but, like Long before him, is over-confident of his abilities when he first attempts the Bronzemen challenge. And you know what? It works. Against all expectations and logic, I found myself urging him to succeed, to see all of that training and hard work pay off, and only occasionally gave a thought to what he might do with these skills once his training was complete. Indeed, when he returns to the dining hall after one failed attempt to beat the Bronzemen, battered and bleeding and laughed at by the others, I caught myself itching for him to dish out a few slaps. Yet just in case we start to wonder if his three years of training have prompted a rethink of his former evil plans, every now and then he breaks into the temple library to search for a book that will help him to become an even more deadly fighter.

As Yinzhi, Carter Wong once again brings a fire and energy to his splendidly shot and choregraphed battles with the Bronzemen, only a couple of which have strong echoes of those of the previous film (notably the 18 blows he has to take, which has a couple of the very same dramatic beats). He’s also very good at looking stern and evil, which he uses to intermittently remind us that he’s not at the Temple for the good of his soul. Increasingly, I found myself wondering where this was all leading, and that’s when…

Okay, I’ve avoiding going into forensic detail about any of the films, so up until this point no spoiler warnings have been necessary, but I just have to talk briefly about what happens when Yinzhi leaves the temple, which does involve discussing how the film concludes. So to avoid any spoilers, hop forward to the Sound and Vision section (or click here). Do it now!

Okay, just how invested I’d become in Yinzhi’s quest is perfectly illustrated by the scene in which his training is technically complete. He’s about to lift the cauldron and get those Shaolin scars, when the monks appear and reveal that they now know who he is, and thus refuse to let him complete this final step. On paper, this is a logical and appropriate punishment for his deception, particularly given the Qing’s determination to wipe out the Shaolin disciples, but when watching it for the first time I absolutely felt Yinzhi’s pain and frustration and thought the monks were behaving like absolute bastards. What, I wondered, is he going to do now? Well, that’s the thing. Only then – once again a testament to how engrossing these time-hogging training sequences are – did I realise that the film had a mere eight minutes to run. How could the story possibly be wrapped up in such a short time? It turns out that it isn’t. After a battle with the unnamed character played by Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kua, one that ends in a manner that leaves the way open for further conflict, Yinzhi makes an angry proclamation and the film just ends. Say, what? Clearly, a direct sequel was intended and may well have been made, something I have no doubt will be explained in the only commentary I’ve not got around to listening to yet.* As it stands, it’s a rather frustrating non-conclusion to another otherwise superb martial arts actioner, one that’s the equal of its predecessor in its original cut, and actually has the edge on the far more widely seen Japanese version.

It was back when I first started reviewing martial arts DVDs that I first learned of the difficulty of producing pristine restorations of films that their makers and distributors believed would have no shelf life beyond their initial release. There was a logic to this in the days before any form of home video existed and when such films were being pumped out at a sometimes extraordinary rate. Why would anyone, it was reasoned, want to re-watch a film a couple of years down the line when there were so many new titles to choose from instead? Prints and even negatives of martial arts films from the 70s thus fell into disarray or were forever lost, a situation that was made worse by the humidity of the Eastern summers, which further impacted on the integrity of unpreserved film materials. Thus, to see eight films from those days looking as glorious they do here is genuinely awe-inspiring. I’ve not been able to confirm who was responsible for the restorations, and the booklet that accompanies this set gives no clues, beyond confirming that they were licenced by Eureka through the Mei Ah Entertainment group, but whoever it was, they did an amazing job.

All eight films are presented in their original aspect ratio of 2.35:1 in 1080p HD, and what’s particularly impressive is the consistency of the restoration and transfer quality. For the most part, the image is sharp with excellent detail definition, something particularly evident on close-ups of faces, clothing, objects or signs. Just occasionally, a shot may appear slightly softer due to the condition of the source material, although some more pronounced cases appear to have been baked into the negative – on The World of Drunken Master this is down to the anamorphic zoom lens used (some shots start soft on wide and sharpen as they zoom in), while on The Old Master a couple were the victim of a rapid shooting schedule and the focus on the camera being just off on shots they likely had no time to reshoot. The punchy contrast really works for the films in the brighter daylight scenes, though do result in some minor swallowing of detail by the beefy black levels in darker settings, but not in a way I found distracting and that may be partly down to my OLED TV. What really knocked me out was the vividness of the colour, which is genuinely lovely on all eight movies, really showcasing the vibrancy of the costumes and the studio sets, which is at its most striking in the opulent décor and costumery of the Imperial Palace interiors. The golden colouring of the Bronzemen on the final two films in the set is also strikingly rendered here. The transfers are free of any former damage or dirt, and all display a fine film grain, albeit one that can occasionally coarsen a little depending on the film stock used and the materials sourced for the restoration. A superb job all round.

It’s a slightly different story when it comes to the soundtracks, which were never high fidelity in the first place, and there’s only so much you can do when with sub -standard audio. In common with their Hong Kong brethren, the films in this set were all shot silent and the voices dubbed and the sound effects added in post-production. Mandarin dubs are available on all eight films, and as the actors all performed their lines in Mandarin, this is always the track that most accurately matches what you see on screen. The dynamic range is often severely restricted, resulting in some abrasive trebles and occasional distorting of dialogue and music, but there is some variation between the individual titles here, with some a little better on this score than others. The contact wallops in the fight scenes are appropriately impactful, and if you route the bass through a subwoofer you will be able to feel as well as hear these sounds.

There is also an English dub available on all of the films except the Japanese cut of The 18 Bronzemen, although there is an English track on the Hong Kong edit of the film. The performances on these English dubs vary from film to film, being perfectly acceptable on some (The 7 Grandmasters, both 18 Bronzemen titles) and comically overplayed on others (World of the Drunken Master, The Old Master), and are sometimes (though not always) not as well mixed into the soundtrack, emphasising the fact that the voices were added in post. There are some other oddities on the English language tracks, with the booming disco music on the Mandarin track of The Old Master massively reduced in volume and punch on the English track, while on Shaolin Kung Fu, some voices in the same sequence and even the same conversation are mixed at completely different volumes (check out the scene in which the Dong Yang rickshaw driver bullies the child vendor and steals his eggs). I’ve not listened to each soundtrack option on all eight films in full, but dipping in and out of the English language tracks, I also noticed a couple of instances where the music score differed from that on the Mandarin original. It should come as no surprise that both the Mandarin and English soundtracks on the reconstruction of the Hong Kong cut of The 18 Bronzemen are the weakest in the set – the dialogue on both are clear enough within the usual restrictions, but the Mandarin track has some background hiss and a regular low-level clicking, and there is audible crackle at times on the English dub.

There is also an optional Cantonese language track on The 12 Grandmasters, World of Drunken Master and The Old Master, which although not as cleanly matched to the mouths of the characters, is usually of similar quality to the Mandarin track. For the record, I watched all eight films with the Mandarin track and English subtitles, which seemed to me to be the truest to how the filmmakers’ intended them to be seen.

As expected, optional English subtitles are available and kick in automatically if you select the Mandarin or Cantonese tracks, but can be switched off if your language skills are up to the task, though you’ll need to do this on your player remote, as I didn’t spot an option to do so on the disc menu. If you choose the English language track, then optional subtitles are provided for translation of credits and in-film text such as shop or street signs.

Audio Commentary on The 7 Grandmasters by Frank Djeng and Michael Worth

The first of four commentaries featuring martial arts movie expert Frank Djeng, the first two of which sees him partnered with actor and martial artist Michael Worth, who in a rather lovely twist had pre-ordered this disc set as soon as it was announced, only to then be invited by Djeng to join him on two of the commentaries. Both men really know their martial arts movies and indeed their martial arts, and of the four commentaries he does for the set, Djeng admits that this was the one he was looking forward to the most (it’s also, adding further confusion to the order, the last one he recorded). Areas covered include information on the actors and on director Joseph Kuo, how the fight scenes are shot and what fighting techniques are used, the influence of Kurosawa films on Kuo, how the unauthorised use of music from American films creates problems for remastering some classic era martial arts movies, and more. As ever, Djeng provides useful translation and detail on Chinese terms and signs, and at one point describes the film as a masterclass in classic kung fu. An excellent commentary that sets the tone for those to come.

Audio Commentary on The 36 Deadly Styles by Mike Leeder and Arne Venema

The first of four commentaries featuring actor, producer and martial arts film expert Mike ‘Big Mike’ Leeder and filmmaker and film historian Arne Venema – both of whom are based in Hong Kong – is bristling with energy from the moment it kicks off, allowing the pair to cover as much ground as Djeng and Jones with an even more explosive level of enthusiasm. We get info on the performers, the links to Jackie Chan movies, the dots on the head that identify a genuine Shaolin monk, the low budgets and financing of martial arts films, how eating in a kung fu movie always leads to shenanigans (their word), the casting of actors with a Jackie Chan look after the huge success of Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow and Drunken Master, this film’s absurd wigs (“What the fuck were they thinking?”), and much more. They point out when the actors are doubled by more skilled martial artists, suggest that Jackie Chan would never be as vindictive as the lead character here, and usefully explain the meaning of a Buddhist symbol that you’ll see in several of the films in this set (including on the bags carried by Shaolin disciples), one that was reversed and adopted by Hitler as the Nazi swastika. Amusingly, a sequence involving the skinning of a real snake has Venema squealing with horror, as he appears to have an even bigger phobia of snakes than Indiana Jones.

Audio Commentary on World of the Drunken Master by Frank Djeng and Michael Worth

Djeng and Worth are back to provide details on actor Jack Long and more info on Joseph Kuo, and also to recall how they both first fell in love with martial arts movies, to note that the lead characters fight almost exclusively over wine, women and food, and to tell us a little about some of the supporting players and even one of the dubbing artists. Djeng explains Chinese word gags that would fly over the heads of western audiences, points out that the zoom shots in which the image is initially soft is the fault of the anamorphic lens used to shoot the scene, and both men praise how well the comedy is integrated into the action.

Audio Commentary on The Old Master by Mike Leeder and Arne Venema

Leeder and Venema return to pick a few justifiable holes in what is definitely the weakest film in this set, but keep the tone upbeat and still praise elements that they believe work well, particularly the black-dressed American fighter whose name nobody seems to know. There’s a lot of information on lead player Bill Louie, plus details on cinematographer Jorgen Wedseltoft, former Peking Opera trainer Jim Yun, public disco dancing in Hong Kong, and more. Such positive talk is balanced by criticism of the occasional problems with the cinematography, the decision to stage the best fight midway through the film, and Louie’s highly suspect Robot Kung Fu, which prompts a weary sigh when it crops up at the end of the rooftop fight. “All the elements are there,” notes Leeder about the film as a whole, “but some of the mix is wrong.”

Audio Commentary on Shaolin Kung Fu by Mike Leeder and Arne Venema

From the introductory information they provide on director Joseph Kuo, I have a feeling this was the first commentary that Leeder and Venema recorded for this set, but it’s every bit as lively and crammed with information and opinion as their others. Here, they talk about the actors, cinematographer Chen Tung, the search find a new Bruce Lee and the ‘Brucespolitation’ movies that this gave rise to, actors not getting credited on martial arts films, how some people get thrown unexpectedly into movies and become stars, and plenty more. There’s some interesting info on Hong Kong from two people who have lived and worked there for years, plenty of praise for the elements of this film that they admire, and an amusingly gross idea for a film titled Texas Chainsaw Shaolin Kung Fu. Venema in particular makes a case here for the possibility that the film was not directed by Kuo and that he instead oversaw the project as producer only.

Audio Commentary on The Shaolin Kids by Mike Leeder and Arne Venema

Here, Leeder and Venema pay tribute to early Chinese hand-drawn video effects, Polly Shang-Kuan Ling-Feng’s talent for lacing beauty with a palpable sense of danger, the use of strong female leads in Chinese and Hong Kong movies before they became a real feature in Hollywood films, and the how Taiwanese stuntmen took even greater risks than their Hong Kong counterparts. Other areas covered include the actors, the genre trope of fights always breaking out in brothels and tea houses, the inclusion of wuxia-style magical kung fu, the issue of film preservation in a country where humidity is an issue, leading man Carter Wong, Jackie Chan’s notorious contract dispute with director Lo Wei, and the notion that the cinematographers and editors were the real heroes of these films. There’s so much more. Another great commentary.

Audio Commentary on The 18 Bronzemen by Frank Djeng and John Charles

For the final two films in this set, Frank Djeng is joined via a pandemic-enforced Zoom call by John Charles, author of The Hong Kong Filmography 1977- 1997 and a former writer for the sorely missed Video Watchdog. Charles’s knowledge of both the Japanese cut of the film – on which they are commenting – and the Hong Kong original is so precise that he is able to identify the source of every borrowed clip and the original order in which everything appeared, the detailing of which starts to make Djeng’s head spin. We get more info on leading man Carter Wong, on a few historical discrepancies, on the trope of women being taken for men when they dress in men’s clothing, the martial arts choreography, the background of the Shaolin Bronzemen and Wooden Men (that’s a different movie), and some welcome detail on how this Japanese cut came to be. Again, hugely informative and entertaining.

Audio Commentary on Return of the 18 Bronzemen by Frank Djeng and John Charles

For their final commentary, Djeng and Charles kick off by expressing a shared opinion that this is the better of the two Bronzemen films, although one of the reasons Djeng gives is that he found the early scenes in the previous movie with its borrowed footage to be too confusing, but admits in the previous commentary that he’s not yet seen the Hong Kong edit. He provides some useful background on the real life historical figures on which some of the key characters are based, applauds the accuracy of the period costumes here, and explains some of the cultural elements, including the fighting styles and stances used. Both men recall how they first fell in love with martial arts movies, and Djeng really presses Charles over why the hardback edition of his excellent book had such a hideous cover, then encourages us to see it out on Amazon for ourselves (I did, and it is pretty bad). We even get an explanation of the origin of a Chinese habit of tapping the table when tea is poured. Once again, a terrific companion to the film.

Booklet

An attractively designed, 58-page illustrated booklet, in which each of the eight titles gets its own essay by film historian, critic and filmmaker James Oliver, which are arranged in the same order as the films in this set. I’m not going to break down the content of each one, but will say that they collectively make for a most enjoyable and thoroughly researched read. I’d suggest that the best way to approach them is to watch all eight films first, and then sit back and read through the whole booklet in one sitting, as the essays are as much about the director and the performers as they are about the films, and being all by the same author, they have a continuity that makes them feel like chapters from the same book, which they technically are, of course. I particularly liked Oliver’s comment on The 7 Grandmasters, my favourite film in this collection – “Quite simply, this is some of the very finest kung fu fighting there is, a masterpiece of choreography and performance.” Amen to that. Unusually for a Eureka booklet, most of the film credits are not included, which I suspect is due to the difficulty pinning down a close to definitive list of them all.

I might question whether the term ‘classic’ in the full title of this box set is applicable to all of the films contained within, but opinions vary, and put eight films by almost any director together and the chances are that most will favour some titles over others. And while I may not find the cartoon comedy of The 36 Deadly Styles funny and have all sorts of issues with The Old Master, both still have their strong points, and that still leaves six absolutely first-rate martial arts films, including one I’d rank amongst the best I’ve seen. The restorations and transfers are extraordinary, the commentaries terrific, the essays in the accompanying booklet are a captivating read, and the inclusion of the reconstructed Hong Kong cut of The 18 Bronzemen is the icing on the cake. If you’re a fan of old-school Eastern kung fu cinema and have not already bought or ordered this Limited Edition beauty, then snap it up quickly before they all disappear. It’s without question one of my favourite Blu-ray releases of 2021. Highly recommended.

|