|

In my younger days I was never quite sure how I felt about the films of Peter Greenaway. He certainly has a distinctive style, and his determination to go his own way with material that precious few others would choose to explore certainly qualified him from the start as an important talent, one who comfortably stood alongside contemporaries like Derek Jarman and Terence Davies. Yet I seem to remember that the main thing I took from my first viewing his widely acclaimed debut feature The Draughtsman's Contract was that it had a great score and the drawings were nice, and while others were praising the admittedly gorgeous visual stylistics of The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover, I found what I perceived to be its underlying air of class snobbery a little hard to digest, if you'll excuse a pun that you'll need to see the film to groan at. I do recall being just slightly amused when Alan Parker, who really detested Greenaway's work (I'm using the past tense because I don't know if he still feels that way), testily described his 1985 A Zed & Two Noughts as "a P and two noughts, a P and two noughts!" but also remember being utterly riveted by his too-little seen TV documentary, Act of God, which – an endless repeat of one musical riff aside – inventively chronicled a series of true-life cases of individuals who had survived being hit by lightning. I was subsequently surprised how engrossed I became in his 1991 take on Shakespeare's The Tempest, Prospero's Books, and five years later I thus trotted along to a screening of The Pillow Book with higher hopes than I'd previously had for a Greenaway film. I recall being impressed, though my principal memory of the screening was of walking out of the cinema and overhearing two women excitably discussing the impressive size of Ewan McGregor's penis. I like to think I got a little more out of the film than that.

Although the presentation is definitely its most initially striking aspect, The Pillow Book is still built on surprisingly solid narrative foundations. The central focus is Japanese girl Nagiko, whose later obsession with calligraphy is installed from an early age by her calligrapher father, who on her birthday each year would retell an ancient creation myth whilst writing kanji characters on her face and her back. As a child she is informed by her aunt that when she reaches her twenty-eighth year, a celebrated work titled The Pillow Book, a diary of observations made by Sei Shônagon during her time as a lady of the court to Empress Consort Teishi, will be 1,000 years old. As her aunt distractedly reads from this work, young Nagiko discovers that her father is being forced to sexually service his older male publisher Yaji in a secret pact that also demands Nagiko's hand in marriage to Yaji's young apprentice when the two come of age. This relationship soon falls on troubled times, with Nagiko's new husband mocking the very notion of her by-now precious birthday ritual. By now Nagiko has started a Pillow Book of her own, and when her angry husband finds and burns it, she calls quits on the marriage and sets off on a road that will leads to her becoming a successful fashion model.

This, I should point out, is effectively just the setup, one that unfolds in non-linear fashion with childhood memories recalled by the adult Nagiko in flashback. With the freedom that success allows, she begins searching for a man who can fulfil her desire by using her body as a literary canvas, a great calligrapher who is also an attentive lover. None of the affairs that she embarks on deliver the satisfaction she craves, but when an English translator named Jerome suggests that she reverse the notion and use his body as parchment for her own writing, she hatches an plan to simultaneously see her own work published and take revenge on the man who so exploited her father.

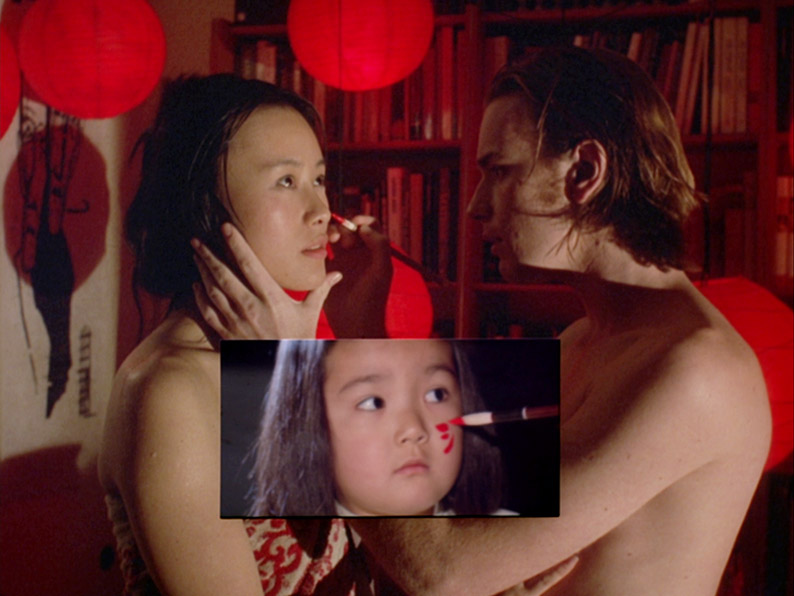

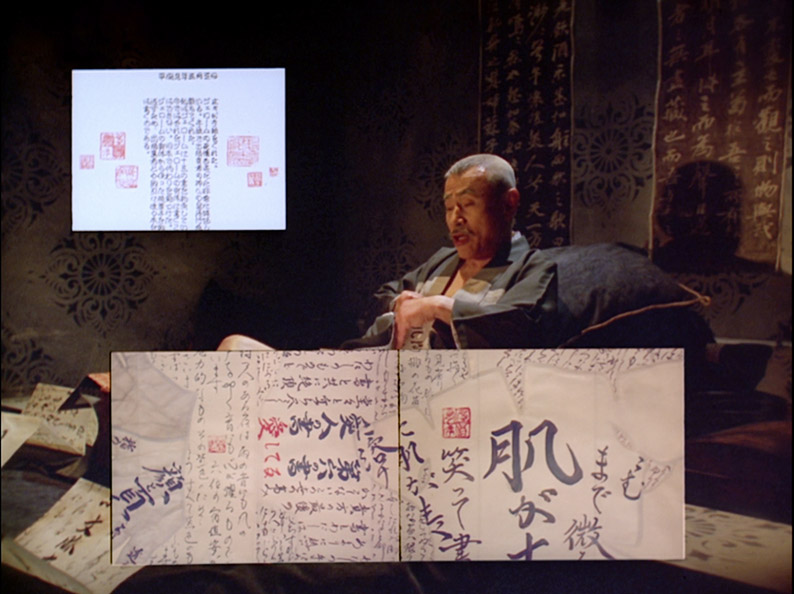

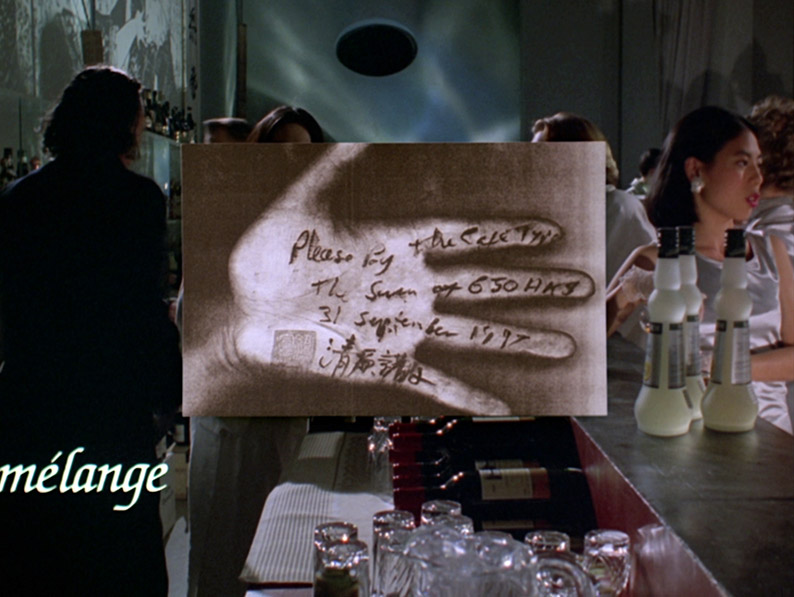

With this as his base, Greenaway tells his story in a manner that both explores and celebrates the specific beauty of calligraphy and particularly the bridge between the painting and the written word that Japanese pictograms represent, whilst simultaneously experimenting with film form and the norms of structured storytelling. Flashbacks switch between colour and monochrome, aspect ratios change on a sometimes shot-by-shot basis, and picture-in-picture overlays are used to examine a scene from alternate perspectives, provide illustrative accompaniment, recall a relevant moment from an earlier sequence, and simultaneously visit two stories or even signal where the story will take us next. This montage of imagery is frequently accompanied by calligraphic text whose function is constantly shifting, providing translations (and occasionally, deliberate mis-translations) of the Japanese dialogue, poetic asides, or a window into the thoughts or emotional state of the central character. Theoretically this should prove confusing or even art-for-art's-sake frustrating but it never does, with cinematographer Sachs Vierny's sumptuous compositions and Greenaway and co-editor Chris Wyatt's intricate montage work combining with an eclectic soundtrack of songs from the likes of Guesch Patt, Tokyo Gasuko, U2 and Lamas and the Monks of the Four Great Orders to genuinely hypnotic effect. I've seen it argued that this richly realised surface detail is perhaps too mathematically precise for the underlying eroticism to really register, but I'm not sure this matters and would suggest that this is not an erotic drama at all but rather a study of the very personal nature of eroticism and the difficulty of finding true sexual compatibility, even in a partner with whom we might be otherwise strongly drawn to.

The cast is certainly a draw here but not without one question-raising blip that I'm guessing will not register as such with others. Nagiko is Japanese, and in move that I applaud and that aids the recognition of temporal jumps, she is played at various stages of her childhood and youth by four different Japanese actors (in no particular order, Kawair Miwako, Ohnishi Chizuru, Takamatsu Shiho and Ishimaru Aki), but once she reaches adulthood she's played by Chinese actor Vivian Wu. Now given the complexity of layering and multitude of subtextual element in this film, I have no doubt that an argument could be made for reading this as a commentary on the shifting nature of identity, how fame effects who we are and how others perceive us, that sort of thing. I should point out, however, that I didn't glean that supposition from the film itself, it's just something I came up with as a possible justification to be offered. Not bad, huh? The problem is that this ethnic switch (and I should point out that on seeing Wu, my Japanese partner immediate barked, "She's not Japanese!"), like the later Memoirs of Geisha, can't help but waken memories of that once too-common practice of having Japanese or Chinese characters played by anyone of vaguely Oriental appearance on the racist pretext that they all look the same. Yeah, I'm a little touchy about that one.

Having said all that, however, I seriously doubt that this is the case here. It's clear that Greenaway has great respect for Japan and its culture, and I would imagine that finding a Japanese actor to play adult Nagiko presented a few problems, requiring as it did an actress who was prepared to bare all repeatedly and do the odd sex scene (although Greenaway seemed to have no problem locating Japanese males who were game). It's worth remembering, after all, that the extremely hostile public response to Matsuda Eiko's performance in Ōshima Nagisa's sexually explicit Ai no korīda effectively destroyed her life and career. You could also argue that Wu's casting was in part dictated by the story's requirement for a girl who could speak fluent Cantonese and English and convince as professional fashion model, though a contrary view might suggest that the decision to have Nagiko learn Cantonese and make her fame as a model was made precisely because Wu was cast in the role (on the commentary Greenaway confirms that the opportunity to work with Wu was instrumental to her casting). In the end it's a compromise that most won't see as a compromise anyway, and it thus all comes down to wither Wu's performance fully justifies her casting, and for the most part it absolutely does. Her unabashed boldness in a role that many would shy away from is genuinely admirable, and in her interactions with other characters and her moments of emotional contemplation and anguish she she is seriously and sometimes touchingly convincing. Only her narration feels at time a little artificial, her English delivery having a mannered air that had me briefly wondering if she had been dubbed in post by another actor. The primarily Japanese supporting cast (that includes veteran actor Ogata Ken as Nagiko's father) are consistently excellent, and a young, fetchingly handsome and – yes – often very naked Ewan McGregor is on fine form as Jerome. And I know that I'm speaking personally here, but none of the nudity in the film feels remotely gratuitous or included for titillation, being as much a reflection of the easy-going attitude the Japanese (and this particular giajin) have to bring naked and bathing together as it is integral to the story being told.

If the film's momentum seems to momentarily stutter during a sdlight gear change following the loss of a key character, considerable compensation is provided by the body books that Nagiko continues to send to Yaji, each of which present themselves to him in a manner that wittily reflects their title and content. The film also revisits the notion of repurposing the corpse of the recently departed from The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover from a different but in some ways no less grotesque angle. It all builds to a pleasingly harmonious conclusion, one that brings the story to satisfying close without disrupting the film's seductive melding of art and literature.

Despite cloudy but positive memories of my first viewing of it 23 years ago, I'll admit to having been a little apprehensive about revisiting this film, but to my considerable delight found myself utterly bewitched by it, probably more so than when I first saw it. It reminded me of how much I have changed as a viewer since in the intervening years and made me acutely aware of how many films I have seen in that time that lacked even a fraction of the imagination, invention and artistic skill on display here. No question of it, this time around I really liked this film. Time, methinks, to revisit some of those earlier Greenaway films I gave little more than a cursory nod to and seek out some of the many that he has made since that I have still yet to see.

The Pillow Book was shot on Super-35mm film, and while it was one of the first features to be edited on Avid computer-based editing software, the film's aspect ratio variations and montage work still had to be processed optically using the edit as a guide. This, combined with the use of various colour tints, would, I'm guessing rule out mastering the film from the original negative without re-compositing all of the shots again from scratch. This, of course, would go a little beyond the usual remastering brief (although the film's original calligraphic subtitles were indeed recreated for this transfer by Michael Brooke) and would likely see Greenaway, should he be involved in the process, unable to resist the opportunity to tinker with the editing, imagery and scene structure and effectively create a different cut of the film. As a result, the image is perhaps not quite as pixel-sharp as a pristine restoration from a 35mm negative, but Film4's HD remaster is still seriously impressive, with an excellent level of detail, beautifully rendered colours, and a contrast range that, within the constraints of the changes made to the image, never feels aggressive or lacking in punch. This picture is also very clean and yes, a fine film grain is visible. Although the aspect ratio is continually shifting, the imagery is constrained within the 1.33:1 Academy frame, which is how co-editor Chris Wyatt believes it should be presented and seen.

The Linear PCM 2.0 stereo soundtrack has also been remastered and is sonically splendid, with a wonderful clarity to the all-important music and an impressive dynamic range for a non-5.1 film, giving a bass solidity to the throat singing that accompanies the opening titles and never feeling annoyingly crisp in the treble notes. Dialogue is also consistently clear, even when it comes close to being swallowed by the music.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are also on board, though the screen really does start to feel a little crowded once they are activated.

Selected Scenes Commentary with Peter Greenaway (38:05)

This partial commentary by Peter Greenaway runs only for the first 38 minutes of the film and is not screen-specific, but is so densely packed with information that it's still a most welcome inclusion. Subjects covered in some detail include the origins of the project, the separation of text and imagery in art and his desire to unify them, the over-reliance on narrative in cinema, his fascination with Japan and its art and culture, the original The Pillow Book and its author Sei Shōnagon, setting up and shooting the film, the long editing process, the costumes, the calligraphers and a whole lot more. He also sings the praises of digital filmmaking with a passion that suggests he is glad to see the back of film as a medium for recording imagery. I'm guessing we're not all going to be on board with him on that.

Chris Wyatt: The Book of the Editor (26:23)

An engaging and educational chat with The Pillow Book editor Chris Wyatt, who worked with Greenaway for many years in various editorial capacities (he began as an assistant) and whose subsequent credits include Shadow of the Vampire for E. Elias Merhidge, This is England and Dead Man's Shoes for Shane Meadows and '71 for Yann Demange. Wyatt has nothing but positive memories of working with and learning from Greenaway (who also began his film career as an editor) and provides some useful specifics of The Pillow Book's two years of post-production. It's here that I learned that this was one of the first features to be edited on Avid, and that the technology was so new that even the simplest of effects had to be rendered before you could see them (a simple cross dissolve could take all of two minutes). He reveals that there's a four-hour cut of the film somewhere that he rather liked, and recalls that when an earthquake in Japan led to a shortage of memory SIMMS that sent prices skyrocketing, he and Greenaway arrived at the location at which they were editing to discover that the entire Avid suite on which they were working had been stolen.

Theatrical Trailer (1:57)

Not the easiest film to sell but this trailer certainly gives it a go, giving a flavour of the multi-layered imagery but ultimately suggesting a story-driven caper with artistic flourishes.

Image Gallery

70 screens of promotional stills (including colour ones from scenes that play in black-and-white in the film, behind-the-scenes photos, scans of press book pages and posters, the most striking of which (as ever) looks to be a Polish one.

Rosa (1992) (15:50)

A short film directed by Greenway, photographed by Sachs Vierny and edited by Chris Wyatt (his first assignment as editor for Greenaway) that is essentially a record of a modern dance performance by Ikeda Fumiyo and Nordine Beauchorf from choreography by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. Formally framed wide shots that deliberately recall Vierny's iconic work on Alain Resnais' Last Year in Marienbad unpredictably cut to mid shots and closeups, while occasional cutaways of a dressed table, towards which Ikeda throws glances, suggests the presence of a narrative that is never explicitly spelt out. As you would expect, the dancing is the key attraction here, which is at its most arresting when the two dancers are interacting with each other. The image quality is excellent, being the result of a new 2K restoration from the original negative.

Booklet

First we have the credits, then a well-argued essay analysing the film and its multiple layers of subtext and meaning by writer Adam Scovell. Next up are extracts from interviews with and articles by Peter Greenaway in which talks about the film, its development, his influences, his use of digital compositing and more, all of which makes for engaging and sometimes revealing reading. Next is a list of ‘5 facts about flesh and ink' prepared by Greenaway after reading Sei Shōnagon's The Pillow Book for the second time in a more complete translation, after which is a reproduction of the first book from Greenaway's published script for the film, which reads more like poetry than a traditional screenplay. Extracts from three contemporary reviews are followed by credits for Rosa and a short but useful essay on it by disc producer Anthony Nield, who explores the connection to Last Year in Marienbad. Bringing up the rear is a page-long piece on the restoration of Rosa.

OK, confession time. I'll admit that there's a slightly nostalgic aspect to The Pillow Book that takes me back to a long ago relationship in which my then partner and I would spent long afternoons painting characters and imagery on each other's bodies, and I thus found it easier than some might to connect with the suggest that this could be an erotic act. Trust me, it can. Big time. But there's so much more to absorb and appreciate here, and I genuinely can't help wondering – as Greenaway himself does on his commentary track – what Greenaway might do with the same material if he had access to the technology we all have at our disposal today. That said, I do suspect that the then newness of the notion of digital compositing and the work that was required to achieve the montage work is part of what helped to make it as special as it is. Either way, the presentation of the film itself on this Blu-ray is first-rate, and the special features, though not as numerous as you'll find on a good many other Indicator discs, are excellent. It's a film that some are going to dismiss and others will struggle with and I do get that, but if you're game then this release is the business and comes unreservedly recommended.

|