| |

'I think audiences can perceive when films have been made simply to play with their emotions and shock them. My films just tend to appear quite innocent, with the feeling that you open the lid and say, "What the hell's that?"' |

| |

Director Miike Takashi |

The three films in Miike Takashi's retrospectively titled Black Society Trilogy are not directly linked by shared characters or connected story threads, but by a small number of common themes. The Black Society of the title is a reference to an underground aspect of Japanese society, one that tends to revolve around criminal activity and gang violence. Here, this is linked to the experience of being an outsider in a foreign land, and how that affects your life, your prospects, and how you are perceived by others.

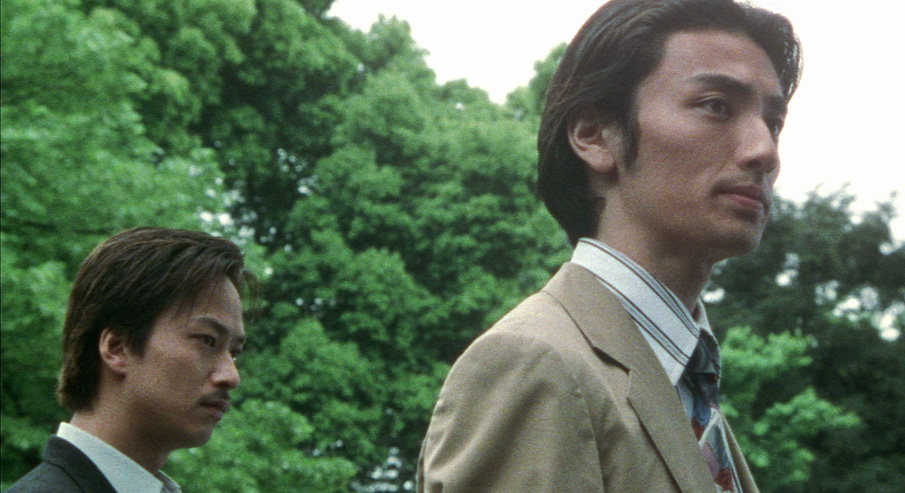

In the first film in the trilogy, Shinjuku Triad Society (1995), a Sino-Japanese detective investigates a band of Taiwanese gangsters in a crime-ridden corner of Tokyo. In the second, Rainy Dog (1997), a superstitious former Japanese yakuza has relocated to the Taiwanese capital of Taipei, where he has found work as a hit man. In the third, Ley Lines (1999), a trio of Chinese immigrant youngsters head to Tokyo with the long-term aim of leaving the country, a journey that involves them in criminal activity and brings them into conflict with local Chinese Triads. Each of the films is different in tone and content, and while all were made on direct-to-video budgets, each is distinctive and memorable in its own way.

| Shinjuku Triad Society [Shinjuku kuroshakai: Chaina mafia sensô] |

|

I once spent a rather wonderful evening in Shinjuku, which has a reputation as the liveliest district in Tokyo, eating and drinking myself into a daze with a group of film students from the city's celebrated Japan Academy of Moving Images. When the trip was first proposed, however, I was a little apprehensive. The reason? This film. I'd never heard of Shinjuku until I first sat down for Miike Takashi's first made-for-cinema feature, but by the halfway mark had decided that if it gave even a small flavour of what Shinjuku was really like, then it's somewhere I'd probably go to some lengths to steer clear of.

Consider the film's opening ten minutes. Following the discovery of the decapitated body on a street in the red light Kubukicho district of Shinjuku, detectives raid a nightclub that is known for its criminal connections and patronage. When no-nonsense detective Kiriya burst into a seedy stairwell, he is confronted by the sight of a young male prostitute named Zhou dishing out a blowjob to a coked-up older client. Following an exchange of looks that suggests the two recognise each other and are startled by the encounter, Zhou pulls up the zip on his client's trousers sharply enough to snag the man's genitals, then pushes him towards Kiriya and slips outside in the ensuing pandemonium. As he leaves the club through an alleyway back entrance, he cuts the hand and then slices the throat of a beat cop who attempts to halt his progress, actions that put the widest of smiles on his face. Kiriya's initial pursuit of Zhou is halted, meanwhile, when he's tripped up by Taiwanese gangland moll, Ritsuko. Arrested and taken down the station by Kiriya, she responds to his questions by spreading her legs and laughingly inviting him to "do" her, to which he responds by busting a metal-framed chair over her face. And believe me, you ain't seen nothing yet.

The cross-cultural theme of the Black Society trilogy is established here at an early stage. Although set primarily in the heart of the Japanese capital, the principal criminal gang here – known as the Dragon's Claw – is Taiwanese in make-up and Kiriya himself is of Japanese-Chinese parentage. As central characters go, he is not the easiest man to like. He's good to his elderly Japanese father, whose health is failing, and his Chinese mother, who has never completely acclimatised to living in Japan. But he treats almost everyone else with annoyance, contempt or hostility or a blend of all three, and is not above taking bribes from the yakuza or treating suspects in a manner that makes Dirty Harry look like a slave to regulation. His temper is not improved by the discovery that his younger brother Yoshihito, for whom he had high hopes, is now working for the lawyer who represents the Dragon's Claw, whose leader Wang is the very man that Kiriya is most determined to take down.

There seems little doubt that Miike was looking to push a few buttons here by staging scenes that can't help but feel designed in part to become the sort of talking points that regular marketing just can't buy. These include one in which a suited gentleman helps Kiriya extract information from an uncooperative male suspect by wrestling and then raping him, and a sequence in which Wang and his chief muscle Karino dictate new terms to the madam of a Japanese brothel (using a phrase they've learnt in Japanese that they keep repeating in unsettlingly machine-like fashion), then respond to her protests by pulling out one of her eyeballs and dropping it in her drink. Yet somehow these excesses do not feel out of place in a crime drama that embraces and revels in the taboo-busting possibilities of exploitation cinema. That said, I'm likely not the only one who was considerable less comfortable with the idea that a call girl would assist a cop who once brutally beat her because she had her first non-drug-assisted orgasm after he lured her to a hotel room and raped her, and I'm still not sure whether we're supposed to be provoked by the fact that Wang is gay or are being asked to just accept his sexual preference without prejudice.

In Shinjuku Triad Society, Miike has reimagined this corner of Tokyo as a battleground where the violence inflicted by warring gangs on each other is met with a proportionately extreme police response. And while the film's detractors have suggested that the more extreme elements are only there at all to spice up what would otherwise play as a run-of-the-mill tale of cops chasing gangsters, I beg to differ. What struck me about the film all these years after my first, eye-opening viewing is how effectively the individual story strands unfold and interweave, and how background information on Kiriya and Wang arrives in small bites and never plays like shoehorned exposition. The biggest reveal on this score comes when Kiriya escorts a prisoner to Taiwan and, against his chief's express orders, stays on to poke around into Wang's past, his temporary allegiance with the initially reluctant Detective Ko allowing us to also learn a little more about him. It's a trip that also delivers two of the film's most effectively understated scenes, the first when a song being sung by a father to his children momentarily transports Kiriya back to his own childhood, the second involving a meeting with a group of children being held at the immigration office that chillingly confirms the nature of Wang's illegal activities.

Cinematographer Imaizumi Naosuke's blend of locked-down shots, smooth tracks and handheld follow shots gives the film rough-and-ready feel of a work made on the move, and infuses the storytelling with an energy and drive that is enhanced by Shimamura Taiji's tight but never attention-grabbing editing. It's a film that saw Miike hit the ground running as a crime thriller director, but by then he had already made twelve direct-to-video movies, four of them the very same year as Shinjuku Triad Society hit Japanese screens. And although most famous for its excesses (or, as Tom Mes has in his commentary track, its exaggerations), when Miike dials it down a notch and more completely integrates the violence into the narrative rather than showcasing it, he's pretty much at the top of his action cinema game, as in the all-guns-blazing raid by the Dragon's Claw on a rival gang's headquarters, or the brutally physical, late film fist fight between Kiriya and his brother. And as unexpected borrowings go, the sly nod to Macbeth that sees Wang vainly trying to scrub the blood of his long-ago murdered father from his hands takes some serious beating.

| Rainy Dog [Gokudô kuroshakai] |

|

Given the hard-boiled and sometimes extreme nature of its Trilogy predecessor, the 1997 Rainy Dog comes as something of a surprise. There are definite thematic similarities between the two films, though the multicultural element of Shinjuku Triad Society has here been inverted by way of a Japanese central character who now lives and works in Taiwan. And while violence is a key aspect of his way of life, it is handled here in a matter-of-fact manner that befits the story and situation, and has none of the gleeful nastiness of its predecessor.

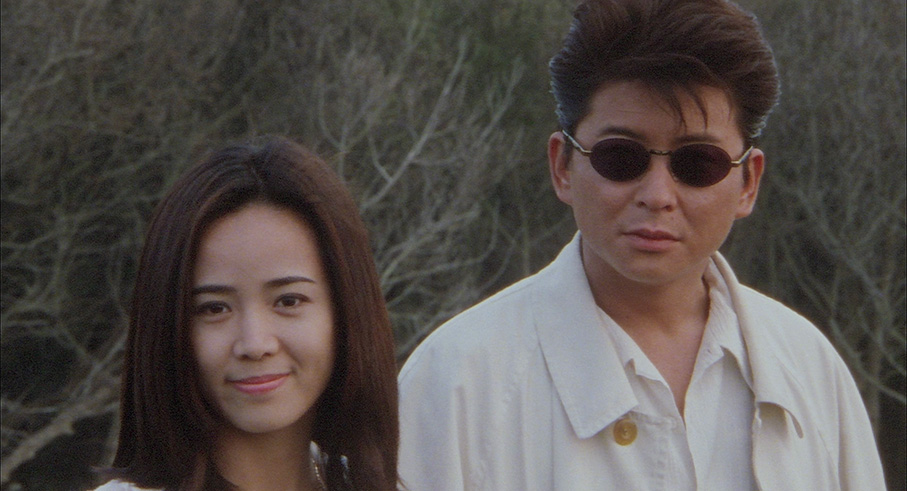

Yûji is a former yakuza now living in exile in Taipei, where he ekes out a living performing hits for a local crime boss. A coldly efficient killer, he has just one superstition, that it is bad luck to go out in the rain. So rigidly will he adhere to this dictum that he will even postpone a hit at the very last second at the first sign of a cloudburst. One day a woman from his past unexpectedly appears and presents him with a mute young boy named Ah Chen, whom she claims is his son and whom she leaves in his charge. Initially frustrated, Yûji at first sticks to his routine and ignores the boy, who silently follows him around, witnessing his misdeeds and even sleeping outside in an alley when he pays a visit to Lily, a prostitute who shares his dislike for rainy days. His life is further complicated when the brother of one of his victims comes looking for revenge, and he could certainly do without the unexpected appearance of an old rival from Japan, one whose only way back to his homeland is to take Yûji's life.

As a director, Miike tends not to be known for his mood pieces, but it is this element of Rainy Dog that proves its greatest asset. The scenes in Taipei back streets and market areas, often shot with a hand-held camera in unhurried takes, really capture the feel of a particularly unglamorous corner of this metropolitan city, one whose frequent downpours play like expressionist reflections of Yûji's melancholia, pulling alleyways and rooms into semi-darkness and repeatedly imprisoning him while others outside are making moves against him. His sense of isolation is at least partly self-inflicted, his rainfall superstition exaggerated by a casual drug habit and his failure to connect with a city that bears only a surface resemblance to the Tokyo of his past. This isn't his home, this isn't his language and these aren't his people, and by retaining a distancing sense of disconnection, it makes them easier to kill.

The arrival of his son initially fails to change this, and Yûji's early refusal to even acknowledge the boy's presence is partially down to his reluctance to lower his guard. One of the very few times he talks to Ah Chen is to tell him, "You're not a dog!" which is, of course, exactly how he behaves, following his father wherever he goes, whatever the circumstances. At one point, he even makes friends with a real street canine, an animal that then kicks against expectations by refusing to accompany the boy when he leaves. As the story unfolds, Ah Chen becomes a physical representation of Yûji's conscience, a constant and troubling reminder of a life he has lost, there every time he looks out of the window and every time he turns around in the street. It is the eventual recognition of this fact that prompts the first change in Yûji when, while attempting to do two good deeds and take care of both Lily and his son, he runs afoul of circumstance and finds himself part of a makeshift family. For the first time, he discovers that he is able to care for the welfare of someone other than himself, a journey of self-realisation that is deftly handled by Miike with little in the way of obvious signposting.

The film's weaker aspects have less to do with breadth than depth, as Miike touches on a string of interesting issues that I would have been happy for him to have spent another half-hour of screen time exploring in more detail. The scene in which Yûji, Lily and Ah Chen march along a beach and then pause to cheerfully dig up an old scooter, for example, has a very real ring of Kitano Takeshi about it, from the beach setting to the oddball family unit. Although a very different film, Kitano's own tale of a (would-be) gangster saddled with the care of a young boy, Kikujiro, probably crammed more character detail into its opening twenty minutes than Rainy Dog does in its entire running time (as did Luc Besson's Leon and Pierre Salvadori's 1993 Cible émouvante [Wild Target], both of which revolved around a similar set-up).

A sense of familiarity also dogs some aspects of the film and just occasionally come close to puncturing its seductive air of plausibility. Yûji, for instance, has the look of an archetypal Hong-Kong cinema assassin, and while his studied moodiness, long white coat and oval sunglasses are cool in themselves, they also make him stand out spectacularly in the very crowds into which his profession dictates that he be able to disappear. That said, Taipei does seem to lack a working police force – just minutes after killing a man in broad daylight in front of multiple witnesses, Yûji is sitting down for a meal with his old rival at an open-air restaurant just a few blocks away and no-one bats an eyelid. The film also confirms a suspicion I've had for some time that assassins only ever feature as the central characters in films to find redemption of some sort, and hit-men with odd quirks have become something of a crime movie staple, from Joe Don Baker's Molly and his fondness for herbal tea in Don Siegel's Charley Varrick (1973), to the pot plant devotion in the aforementioned Leon.

Later in the story, Miike comes close to throwing caution to the wind by staging a series of gun-battle clichés in quick succession, including the old "treasured object in the pocket stopping the bullet" gag, which has been piss-taken in everything from Under Fire (1983) to The Simpsons, although the victim's incredulity and what has happened just about sells it here. And I'm sorry, but almost from the moment I learned that Yûji's son was mute, I just knew that that he would rediscover his voice at a crucial point of emotional bonding later in the film.

But if these small niggles prevent a good movie from becoming a great one, at least for this viewer, it doesn't take away from how damned fine a film Rainy Dog still is. An atmospheric and involving crime drama with dark edge and strong replay value, for newcomers to Miike's work it's is as good a way in as any (it's certainly one of the least confrontational), though I'd still suggest that there are specific pleasures to be gained from watching it as part of the Trilogy.

| Ley Lines [Nihon kuroshakai] |

|

If I'd come to the third film in Miike Takashi's Black Society Trilogy cold, with no knowledge of who was in the director's chair, the first few minutes might just have convinced me that I'd stumbled across a previously unseen work by Kitano Takeshi. Consider the first post-prologue sequence. A suited public servant, framed in locked-down mid-shot, repeatedly refuses to process the passport application of an unseen applicant because the person in question is on parole. The shot is held for considerably longer than would be considered logical by western cinema standards, before cutting to a reverse angle of the agitated young man whose application has just been so soundly rejected. We then switch to a high-angle wide shot of the room, as it might be viewed from a security camera, as the young man walks over, picks up a large pot plant, and throws it straight in the head of the clerk. The scene then cuts sharply to one in which the young man is being given a talking to by either a police official or his probation officer (it's never confirmed which), and it's clear that this is not the first conversation of this sort that they've had. When the boy brushes the words off with "I've heard it all before," the official angrily knocks his teacup over, spilling its contents into the boy's lap, to which he fails to react in the slightest. Long before we even get to learn the young man's name, we know enough to have an opinion about him and take a good guess on where the story may head.

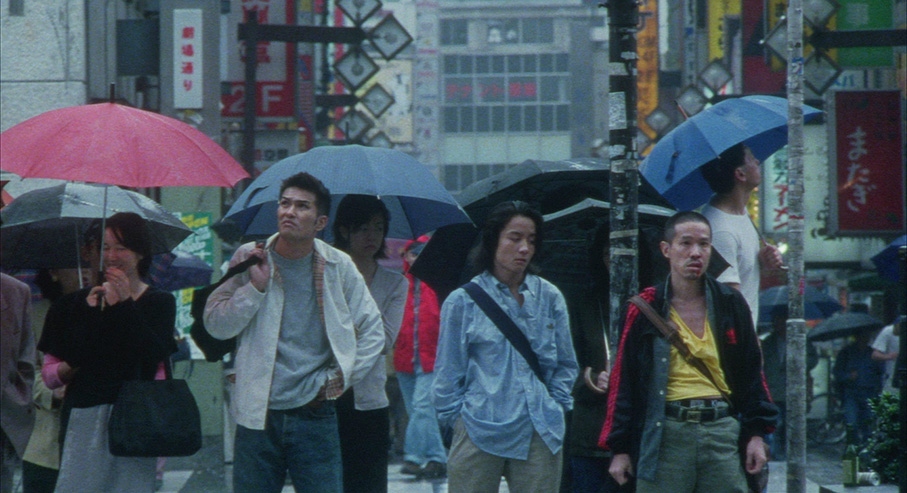

The boy's name is Ryuichi, and we learn more about him when he gets home and all but ignores his agitated mother's remarks about getting a job, words that are delivered in Cantonese rather than the Japanese of the preceding scenes. Ryuchi, we can surmise, is one of the two young children being badmouthed by other kids for being "stinky" Chinks and told to go back to China in the heavily tinted, 8mm film-style prologue – little wonder that he has grown up with an attitude. His younger brother, Shunrei, on the other hand, is calmer and more studious, something established less by the shot in which he shown working on his studies when Ryuichi first drops by than the fact that he's still in the same position a couple of hours later when his brother gets back after an evening of kicking up trouble with his mates. By this point, Ryuichi has made a decision about his future. "Look after Mum and Dad," he tells Shurei as he packs a bag and heads for the station, where he and his friends are planning to take a train to Shinjuku, but it turns out that only his ever-so-slightly dotty childhood friend Chang is prepared to make the journey with him. Well, not quite. Clearly unwilling to be separated from his brother, Shurei gives chase on his scooter to join them, but shortly after they reach Tokyo, all three are fleeced by Shanghai born prostitute Anita, and end up on the streets of Shinjuku with no money, no food and nowhere to stay.

Where the opening scenes of Shinjuku Triad Society are energised and largely incident-driven, those of Ley Lines are largely character-focussed and more sedately paced. Although set partly in Shinjuku's criminal underworld, this is less a crime thriller than a character drama, a film about a journey – physical, emotional and educational – undertaken by three friends as they look for ways to make money and secure passage on a cargo ship to Brazil, where they have (perhaps unrealistic) dreams of starting a new life.

This proves to be an enthralling and often unpredictable ride, as the seemingly mismatched trio of troublesome Ryuichi, hyperactive Chang and introverted Shurei chance their way into selling home-brewed toluene (the component of glue that makes it worth sniffing) for small-time criminal Ikeda, whom they meet through a cheerful African immigrant with the adopted name of Barbie. Their attempts to locate a source for fake passports eventually brings then into conflict with local Chinese gangster Wong, but also opens the door to possible escape to Brazil as stowaways on a cargo ship. All they need to do is raise the considerable sum required to pay for their passage, which leads them down a potentially dangerous path.

If you came to the Black Society Trilogy via Shinjuku Triad Society and expect the two films that followed to have a similar tone, then you're in for either a pleasant surprise or a disappointment, depending on your preference. If seen a couple of negative reviews of Ley Lines, but both take a huffy "oh, it's so boring" tone that suggests the writer's principal peeve was the lack of violence and amoral action. Both are on show here, as they were in Rainy Dog, but as with that film the violence here is brutal, realistic and not designed to be savoured for its taboo-busting extremity. And Ley Lines is always focussed on the fate and wellbeing of its ramshackle trio, which expands to include Anita after she suffers repeated abuse from her pimp and a particularly nasty client and is aided and comforted by Shurei, just as Ryuichi is receiving a serious beating from Wong's men.

Ley Lines is an enthralling and, dare I suggest, impressively mature work from Miike, one in which I genuinely cared for the characters and winced every time they made a suspect decision or fell victim to the hands of fate or their own naiveté. If there's a weakness, it lies in the curse of a convention that tends to seal the fate of any young upstart who thinks he or she can stick it to the world of organised crime without paying a price. It's something that casts a very real pall over the film's final third, though it's to Miike's credit that although some aspects of the story play out as predicted (I can say no more without getting into serious spoiler territory), he still delivers a couple of genuine surprises and one of the best and most moving closing shots of his career.

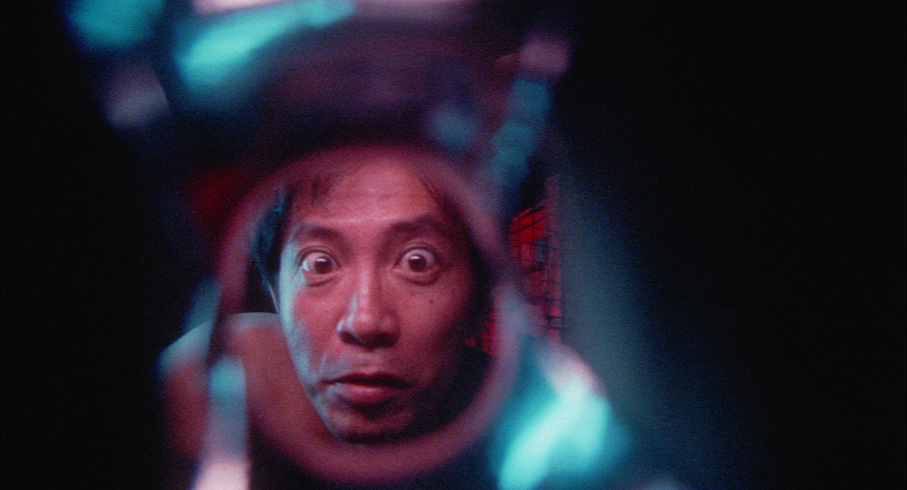

Cinematically, the film follows Rainy Dog's lead in its observational approach and refusal to accelerate the pace through overactive camerawork or machine-gun editing, and is all the better for it. It's not without its share of visual tics, from the occasional use of overpowering tints to the short explosion of quick-fire pop video imagery used to create the sensation of a horror that you'll likely be glad we were spared from seeing. And frankly I'm not sure what to say about the shot in which the action is viewed from the inside of Anita's prised-open vagina. Yes, you read that right.

If I had to choose a favourite from the Black Society Trilogy, it would probably be Ley Lines, which for me just gets the jump on Rainy Dog by allowing us get to know the characters on a personal level and care for their fate. Impressively performed by a cast that includes Trilogy favourites Aikawa Shô as Ikeda and Taguchi Tomorowo as Chan, it's one of Miike's most quietly humanist films, and one of his most arrestingly character-centric.

If the title of this short aside suggests that I'm about to tell you that the films have been cut for this dual format release, then fear not. There is a degree of censorship at work here, a little in Rainy Dog and a bit more in Ley Lines, but it appears to have been self-imposed. Nonetheless, it's execution is still a little strange. The first instance occurs in Rainy Dog when Yûji's slightly crazed rival (played with some energy by Taguchi Tomorowo) urinates over an industrial balcony in a message to a city he proclaims to love. Now at the time of the film's release, the on-screen display of male and female genitalia was strictly forbidden in Japan, and it seems clear that the pissing was done for real here and that Taguchi's member was clearly visible. Miike (who should have realised this when he shot it in the first place, and possibly did) was thus left with two choices, to cut the sequence from the film or obscure the offending body part. He chose the latter, but not using the digital mosaic that was (and possibly still is) the mainstay of the Japanese porn industry, but seemingly by scratching a squiggle on the film itself, which animates like a bag of hyperactive luminous worms. This same effect is used twice in Ley Lines, but here it is joined by the bleeping out of what we can assume from the context were racially driven insults, ones that are appropriate for the characters and the conversation in question but possibly also ran afoul of Japanese law. The English subtitles respond in kind by replacing the censored words with ****.

When I first saw Shinjuku Triad Society and Rainy Dog on DVD, I was struck by how grubby both films looked, and thus was looking forward to seeing them all polished up and pristine looking on Arrow Blu-ray. If you're similarly fired up with anticipation at this prospect then hold your horses, because the transfers here, though high commendable, do not completely overturn that unfavourable first impression. I've been unable to confirm whether Shinjuku Triad Society was shot on 16mm, which was apparently common for V-cinema features, or 35mm, the standard format for cinema releases. Certainly, there are sequences throughout the film where the image has a softness and lack of punch that would be consistent a 16mm blow-up, particularly if you're shooting by available light in dim alleyways and darkened rooms, which also delivers a somewhat glummer and sometimes earthier colour palette. Intermittently, though – a close-up of Ritsuko's wolf bane as it's being watered is a good example – the image really pops, boasting lush greens on the leaves and a crisp level of detail, and get the characters out of the gloomy nightclubs and onto the neon sign bathed night streets and the colour really sings. Rainy Dog also has its share of glum natural lighting and detail-swallowing shadows in some of the interiors, but the image is generally more robust here and the detail sharper, though the still very visible grain and low light shooting keep it a fair few notches away from reference quality. A couple of times – notably when Yûji sits down to eat with his former nemesis at a street café, the sharpness does soften (although something about the movement in this sequence made me wonder if the camera was set at the wrong frame rate and the shot was corrected in post-production), as does the contrast when the light levels drop, but this is still a big step up on the DVD. Best of all is Ley Lines, whose detail is more consistently crisp and its colour more vibrant, but it still has its share of glummer-looking shots both inside and out, though here it definitely feels like an aesthetic choice. All three films are clean of dust and damage, and all are framed in the original 1.85:1 aspect ratio. Yes, the image rarely sparkles, but given Arrow's impressive track record and commitment to delivering the best transfers they can, I'm guessing that this is as good as the films are likely to look. It's certainly best I've seen them.

All three films sport Linear PCM 2.0 stereo tracks and all are in good shape, with clear dialogue, lively rendition of music and sound effects (punches deliver a serious audible wallop) and subtle but clearly audible frontal separation. The sonic range on Rainy Dog and Ley Lines is particularly good, delivering solid bass for a non-LFE enabled track and no nasty crispiness at the treble end of the scale.

Optional English subtitles kick in by default on all three films. Handily, the switch between Japanese and other languages such as Cantonese or Mandarin – which can be significant – is indicated on all three discs by placing the least commonly spoken language in that film (non-Japanese languages in Shinjuku Triad Society and Ley Lines, and Japanese in Rainy Dog) in square brackets. Impressively, the brackets change shape at one point in Shinjuku Triad Society to indicate when a suspect is speaking in a dialect unfamiliar to his interrogators.

Commentaries on all three films by Tom Mes

One of my very favourite commentators on Japanese cinema, author, screenwriter and Midnight Eye writer and co-founder Tom Mes, here takes on the muscular task of providing commentary tracks for all three films. Although less densely packed with facts and trivia than some of his previous commentaries, there is still plenty for anyone not expertly versed in these films, their director or Japanese V-cinema to savour. More than once he goes into some detail about what the term Black Society actually means (my glib overview at the top of this review barely scratches the surface), provides plenty of information on Miike, his films and several of the actors, as well as highlighting elements that were reworked in some of Miike's later films. There's some interesting analysis of individual characters and scenes and of Miike's cinematic technique, and he repeatedly returns to one the central themes of all three films, the coming together and eventual self-destruction of a surrogate family unit.

Show Akikawa: Stray Dog, Lone Wolf (21:42)

An engaging interview with still busy actor Akikawa Shô, who first worked with Miike on Rainy Dog and first met him on the shoot of Imamura Shôhei's The Ell [Unagi] – apparently he couldn't believe that this man was a director when he first came up and introduced himself. He recalls his first film acting jobs and talks about how Miike works with his performers, as well as providing an interesting breakdown of the character of Yûji in Rainy Dog.

Takashi Miike: Into the Black (45:07)

An always welcome interview with director Miike Takashi, who kicks off by revealing that he wanted to be Bruce Lee, that he always hated studying, and that, "as a kid, the only thing I was good at was running away, so I've been running away ever since." He talks about his early career in V-cinema, his fruitful partnership with producer Kimura Toshiki (who disliked what the "old guys" were doing and whose mantra was "Let's make more interesting stuff"), why he enjoys the challenge of finding solutions to budget-imposed problems, and a whole lot more. There's quite a bit on some of his regular cast members, and he claims that filmmakers peak in their 30s and 40s and that he couldn't make films like the Black Society Trilogy anymore. Good stuff.

Also included are the original Japanese Trailers for Shinjuku Triad Society (1:25), Rainy Dog (1:27) and Ley Lines (1:41), all edited at a similarly brisk pace, but more accurately aligned to the individual films by the choice of music for their soundtracks. The spoilers are there, but shoot past too quickly to be a major issue. Surprisingly, some of the more extreme material from Shinjuku Triad Society is included, albiet briefly.

The first pressing also includes a Booklet, which includes separate essays on each of the three films, all of them excellent reads: A Love Story Both Sickening and Sweet: Shinjuku Society by Samm Deigham; Cities of Sadness: Rainy Dog by Tony Rayns; and We've Gotta Get Out of This Place by Stephen Sarrazin. The notes on the transfer are briefer than expected and reveals only that the the HD masters for this release were made available by Kadokawa Pictures, but there's plenty on the subtitles, plus credits for all three films and still images from each.

Despite some small shortcomings in the image quality, which are likely down to the source material, for Miike Takashi fans this should be considered an essential purchase. All three films are impressive in their way and are different enough in tone and content to never feel like the variations on a theme, which they essentially are. Solid transfers (within the above discussed limitations), enlightening commentary tracks and a couple of enjoyable interviews make this easy to recommend.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for all Japanese names in this review.

|