PART 2 |

| |

"I agree with Dante that the hottest places in hell are reserved for those who,

in a period of moral crisis, maintain their neutrality. There comes a time when

silence is betrayal. The truth of these words is beyond doubt, but the mission

to which they call us is a most difficult one: even when pressed by the demands

of inner truth, men do not easily assume the path of opposing their government's

policy, especially in time of war, nor does the human spirit move without great

difficulty against the apathy of conformist thought within one's own bosom." |

Dr King, from his speech Why I am Opposed to the War in Vietnam, 1967 |

| Documentary, Distribution, and Reception |

|

The arrival of docudrama, docusoaps, and reality television in the 90's, and the preponderance of those forms, which continues unabated, is in marked contrast to the ongoing problems of funding and distribution faced by those wanting to work within traditional documentary frameworks. It is a reality that encourages self-censorship and discourages daring. Whatever we might think of TV today, it certainly doesn't provide a home for documentaries to the extent it once did. Meanwhile, although theatrical distribution of documentaries has increased, it remains an elusive dream for most documentary filmmakers. Part of the solution to those problems of distribution lies in film festivals, film clubs, and film libraries like Films for Action, but any widespread, long-term solution will require a change in the way audiences are perceived. If funders, producers, directors and distributors look down their noses at us, and regard us simply as a means of making money, they will invariably assume that the dramatization of fact will reach wider audiences and, therefore, make more money for them.

Mea Maxima Culpa goes some distance towards analysing how a corrupt power structure operates, but, when Gibney tastelessly and tactlessly refers to his film as "a sex mystery," he reveals much about his lack of faith in facts and ideas. He reveals much more about a lack of faith in an audience for plain facts and ideas presented plainly. Alex Gibney and Shola Lynch go just as far as the prevailing wisdom about the reception of films allows them to go. The public, we've long been told, won't watch difficult documentaries, and factual films can't reach audiences without attempting to entertain them. The situation in television has got worse since Ed Murrow's broadcasting days, as George Clooney reminds us in his fictional account of Murrow's clash with McCarthy, Good Night and Good Luck.* Like Murrow, I can provide proof, albeit it anecdotal evidence, for a gnawing hunger for information and documentaries.

A fortnight ago, I was be back in the eves of Sands Film Studios, where I met David Rose and where I regularly attend a weekly film club, to watch Jennifer Baichwal's documentary Manufactured Landscapes. The Sands Cinema Club is run by a French cinéaste, Olivier Stockman, who fell in love with film one night in Paris, in May 1968, after his parents allowed him to stay up for a late night TV showing of Eisenstein's October. Later, he was inspired to make films by Francois Truffaut's La Nuit Américaine/Day for Night. Olivier wrote to Truffaut requesting permission to use his idea, which the director granted, on the understanding that he be shown the finished film. Truffaut liked the results and took Olivier under his wing. In 1979, when Olivier told his mentor he wanted to move to London, Truffaut furnished him with a list of his English contacts. On his first night here, he stayed with a friend of Truffaut's, whose house had been used on a Sands location shoot. The following day he visited Sands Film Studios to view rushes. He was offered work, which he gratefully accepted, and he has lived and worked at the studios ever since. Olivier programmes seasons grouped around particular years, so we experience weekly slices of world history and world cinema. Whenever he screens documentaries the response is always overwhelming. Three weeks ago, when we watched Listen to Britain, there wasn't a spare chair or sofa seat to be had in the cinema. For that screening of Manufactured Landscapes demand was such that Olivier had to add a second early evening screening to the already scheduled one.

Of course, the time is long gone when documentaries were accepted as a 'pure' representation of 'the truth', as 'authentic' reports presenting a pristine mirror to 'reality'. We now recognise that the authorial voice is present in all films, even in the most austere of attempts to produce 'pure' documentaries. All participants in the production and reception of films possess prejudices that compromise and jeopardize objectivity. All films are formed and informed by the ideological contexts at play during their production. All images have ideologies stuck to them. All films are political. Rodney Ascher's thought-provoking, entertaining documentary Room 237 demonstrates those points. Ascher's film directs us to the politics in Stanley Kubrick's The Shining. In Room 237, Bill Blakemore proposes we read Kubrick's horror film as a metaphor for the genocide of Native Americans. Geoffrey Cocks, meanwhile, sees allusions to the Holocaust in it. As Jonathan Gottschall says in his book The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human, "We screen films with happy endings in our minds, where all our wishes . . . come true. And we screen little horror films, too, in which our worst fears are realized." Or, as Robin Wood put it in his anthology, The American Nightmare: "The true subject of the horror genre is the struggle for recognition of all that our civilization represses and oppresses."

We now accept that cinematic representations of reality are mediated and will always be partial, contingent, inconclusive and elusive. As we've seen, John Grierson and the filmmakers he nurtured didn't see things that way. Despite Grierson's definition of documentary as "the creative treatment of actuality," and despite Paul Rotha's description of it as "the dramatization of fact," Grierson, his disciples, and his rivals largely regarded documentary representations of reality as unproblematic. A fact was a fact they felt, and filmed facts no less straightforwardly so. The formal and theoretical challenges of Cinéma vérité, Free Cinema, and Direct Cinema – challenges facilitated by technological advances – were launched from essentially the same premises. Raoul Coutard, Jean Rouche, et al in France; Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz, et al in the UK; and of Richard Leacock, DA Pennebaker, et al. in the US all thought of the treatment of fact in much the same ways the Grierson school directors did. The Direct Cinema directors, in particular, those filmmakers described by Brian Winston as "the second wave of Griersonian documentarists," backed themselves into a theoretical corner in their ardent, idealistic defence of documentary 'authenticity'. Leacock spoke for most of those associated with Direct Cinema when he argued that the filmmaker's main problem was how to represent "what's happening" and convey "the feeling of being there." The imprecision of Leacock's terminology reveals the theoretical knots Direct Cinema tied itself up in, and then tightened. In Noel Carroll's famous phrase: "Direct cinema opened up a can of worms and then got eaten by them."

It is not, however, primarily dissatisfaction with earlier models of documentary theory and practice that has driven documentary in the direction of narrative. Nor has documentary moved in that direction due to any problem intrinsic to the mimetic qualities of the mechanical media. As I suggest above, the tendency toward the 'dramatization' of fact flows from the commercialization of cultural life that accompanied the shift of political power to the right over the last three decades. It is a by-product of social fragmentation, cynicism, and a loss of faith in human agency and solidarity. In the absence of a sense of social cohesion and a general belief in the possibility of change, the documentary director is left stranded, unsure of an audience, with little but storytelling to fall back on. At this point, I cannot resist citing one of my favourite pieces of writing, and an allegory germane to any discussion of audiences:

"In the United States . . . recent public opinion polls have revealed that an actual majority of young people in their teens, the voters of tomorrow, have no faith in democratic institutions, see no objection to the censorship of unpopular ideas, do not believe that government of the people by the people is possible, and would be perfectly content, if they can continue to live in the style to which the boom has accustomed them, to be ruled, from above, by an oligarchy of assorted experts. That so many of today's well-fed young television watchers should be so completely indifferent to the idea of self-government, so blankly uninterested in freedom of thought and the right to dissent, is distressing, but not too surprising.

'Free as a bird,' we say, and envy the winged creatures for their power of unrestricted movement in all the three dimensions. But, alas, we forget the dodo. Any bird that has learned to grub up a good living without being compelled to use its wings will soon renounce the privilege of flight and remain forever grounded. Something analogous is true of human beings. If the bread is supplied regularly and copiously three times a day, many of them will be perfectly content to live by bread alone - or at least by bread and circuses alone . . . 'For nothing' the Inquisitor insists, 'has ever been more insupportable for a man of a human society than freedom'. Nothing, except the absence of freedom; for when things go badly, and the rations are reduced and the slave drivers step up their demands, the grounded dodos will clamour again for their wings - only to renounce them, yet once more when times grow better and the dodo-farmers become more lenient and generous. The young people who now think so poorly of democracy may grow up to become fighters for freedom. The cry of 'Give me television and hamburgers, but don't bother me with the responsibilities of liberty,' may give place, under altered circumstances, to the cry of 'Give me Liberty or give me death'."

That is an excerpt from Aldous Huxley's Brave New World Revisited, written in 1959. Despite his groundbreaking experiments with LSD in the 50s, Huxley can have had no perception of the explosion of radicalism around the corner or of the ways the young would challenge the dodo-farmers in the 60s. We have learned to laugh at those who considered history at an end, and we may yet laugh at those cynics who now say radical change is impossible. Alex Gibney and Shola Lynch speak for the general consensus when they say that documentaries must entertain us in order to be heard, an idea that represents an aspect of the retreat from ideological and political contest that has intensified over the past three decades. The unlikely figure of Sophie Fiennes, with Slavoj Zizek's help, has sought to address those lacunae in The Pervert's Guide to Ideology. In Fiennes' film, Zizek talks, entertainingly, about the ways ideology permeates cinema and our wider culture. After a Festival screening of the film, I eavesdropped a conversation that hints at how far the flight from politics has gone. Coming out of Cineworld, Haymarket a woman was talking to her companion about Zizek: "It's a shame because he's quite funny when he wants to be. I just wish he'd tell more jokes and not bang on about politics. I didn't understand half of it." There are dangers in presenting unfashionable ideas in fashionable ways, in underestimating audiences, in capitulating to the idea that entertainment is an essential prerequisite for enticing folk toward 'difficult' subjects, and in assuming that this process is inevitable.

Much the same arguments can be used about information and documentary as one of Aldous Huxley's pupils at Eton, Eric Blair, used about linguistic usage. In his celebrated essay Politics and the English Language, Orwell writes: "Our civilization is decadent and our language – so the argument runs – must inevitably share in the general collapse . . . but an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely. A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier to have foolish thoughts. The point is that the process is reversible." Where documentary is concerned, complex ideas can be sidestepped or reduced to near meaninglessness, audiences can come to view ideas as an unwelcome distraction from the expected entertainment, and an emphasis on entertainment can abet the vicious circle within which concentration spans are gradually diminished by simplified argument and arguments about diminished concentration spans are then used to further water down 'difficult' content with entertainment.

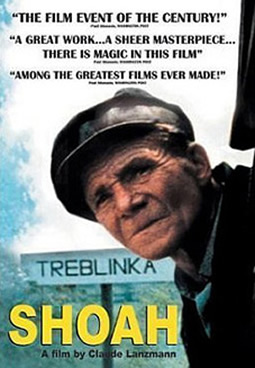

If Humphrey Jennings' Listen to Britain, with its lyricism and hypnotic rhythms, its intoxicating collagist experimentation, was at odds with Bill Nichols' definition of documentary as a discourse of sobriety, Claude Lanzmann's Shoah is its embodiment. Nobody, is about to argue that documentaries should be dull, even if many think they are, and Shoah shows that exacting rigour can pay dividends and win audiences. It's a question of what is proposed and presented as interesting, and of how we read the ideologies stitched into films. By the same token, I hope nobody would argue that Claude Lanzmann's documentary on the Holocaust should be more entertaining. You don't, as Lanzmann did, shoot 350 hours of film, in 14 different countries, over a decade, on such a subject, nor release it as a 566-minute-long film, if a desire to entertain audiences is at the forefront of your mind. And yet, for all Lanzmann's rigour, Shoah is no less marked by its director's politics than any other film, indeed more so than most. I met Lanzmann at La Cinémathèque française in January 2008, after a round-table discussion of Shoah, chaired by former Cahiers du cinéma editor and Cinémathèque director Serge Toubiana. I asked Lanzmann if he didn't feel he should have mentioned the non-Jewish victims of the Holocaust: the men and women of the political left, the gypsies, the gays, the disabled, and mentally ill. He was snappily dismissive of my question. When I met him again last June, after a screening of Shoah at the Prince Charles, Leicester Square, I repeated my question and he repeated his answer: no, he'd left nothing essential out of the film.

Pauline Kael, arch populist and lover of entertainment that she was, may have had a point when she sniffily described Shoah as, "A long moan. It's saying 'We've always been oppressed, and we'll be oppressed again." Lanzmann's Zionism blinded him not only to Nazi crimes against 'other' victims of the Holocaust, but also to the crimes of Israel. In a pointed reference to Emil Fackenheim's above-mentioned quote and as a reminder of those the Israeli state displaced, Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish named his final book, In the Presence of Absence. The Arabic phrase an-Nakba is used by the Palestinians to describe their own ongoing 'catastrophe' or Shoah. It is left to Israel's Eyal Sivan to set the record straight, present the anti-Zionist case, and act on Walter Benjamin's advice that we should "brush against the grain of history." Despite its evasions and elisions, Shoah is darkly beautiful in ways Mea Maxima Culpa and Free Angela and All Political Prisoners are not. Simone de Beauvoir, who Lanzmann lived with for several years, was struck by the lyricism and hypnotic rhythms of Shoah. She said of the film: "I would never have imagined such a combination of beauty and horror." It is partly its lack of embellishment that make is so. In her essential work on documentary, New Documentary, Stella Bruzzi notes Lanzmann's "pervasive eschewal of disruptive cinematic techniques for denoting elisions of time and thought such as jump cuts, montage, rapid zooms or pans." Bruzzi also points out a significant irony about Shoah, "that it is easier to watch than the archive footage of the Final Solution that Lanzmann is so convinced we have become immune to."

| The Truth is Hard to Swallow |

|

Films like Lanzmann's aside, documentaries have become increasingly imbued with the devices of narrative film. Meanwhile, fiction films have increasingly borrowed the claims to truth of documentary and many of its formal devices. Even Beasts of the Southern Wild, a film uses fantasy to reflect a child's point of view, borrows from documentary: in the Cannery Row drinking scenes, in particular, extensive use is made the rough-and-readiness of vérité style that used to be called 'wobblyscope'. Documentary seems to have been relegated to an apprenticeship role, with directors seemingly beginning in factual film only to turn to fiction later, almost as part of a career progression (Nick Broomfield, the Dardennes Brothers, Ken Loach, etc). I remember thinking things couldn't get any worse when Richard Linklater took a great piece of investigative journalism by Eric Schlosser and turned it, with the author's help, into Fast Food Nation, a comedy starring Ethan Hawke, Kris Kristofferson, Patricia Arquette and Bruce Willis. I assume the film's producers were not being intentionally ironic when they elected to promote the film with the slogan "The Truth is Hard to Swallow." At last year's London Film Festival I watched and reviewed Tahrir 2011: The Good, The Bad and The Politician, a documentary about the Arab Spring and the ongoing Egyptian revolution; at this year's festival I watched Winter of Discontent, which covers similar ground - as a story, a love story.

The increased seepage or blurring between non-fiction and narrative film, often presented as formal daring, produces some incredible results. It also represents the apotheosis of the trend toward films as 'closed' spectacles to be consumed by audiences and, as such, is the antithesis of the oppositional tendency that sees films as the embodiment of open-ended, problematic ideas and formal strategies requiring interrogative work on our part. Like Alex Gibney's Mea Maxima Culpa, Shola Lynch's equally excellent and similarly flawed film Free Angela and All Political Prisoners is an entertaining spectacle that commands our undivided attention, but asks nothing of us in return, expect our money. That's an idea I'll return to after I've considered Lynch's film, which, even more than Gibney's, exemplifies the belief that information can only hit its target if it is packaged as entertainment.

| Free Angela and All Political Prisoners |

|

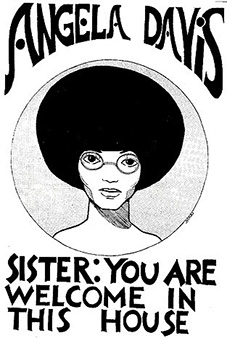

It would be impossible to make an ordinary film about a woman as extraordinary as Angela Davis. In its one hundred and one minutes, Shola Lynch's Free Angela and All Political Prisoners offers a compelling glimpse into what made Davis extraordinary and provides audiences with a hundred and one reasons to learn more about her life and times. Angela Davis should need no introduction. Interviewed after the film's premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival in September, Shola Lynch wondered, "Why isn't she the poster child for all that's great in America?" Indeed. The legendary author, academic and activist embodied the idealistic energy and anger of the late 60's and early 70's. During that tumultuous era of political and intergenerational conflict, Angela Davis was in the eye of the storm and her impassioned, articulate arguments for feminism and socialism, against racism and injustice, had a ready audience. She came to be recognized the world over as an international icon of the radical left and the Black Liberation Movement. Her fierce intelligence, militant eloquence, and unbending defiance of authority ensured she was as loathed and feared by the political establishment as she was loved and respected by those who challenged its power. She has subsequently been airbrushed out of official accounts of history, as unrepentant revolutionaries tend to be, but she remains a potent symbol of progressive politics.

Shola Lynch is an extraordinary woman in her right. She began her life in front of the camera rather than behind it, as a child actor on Seasame Street. While studying for her degree, she trained as a track and field athlete, competing at 800m and 1500m at national and international level. She has said her experience as a top-flight athlete taught her that winning is not the important thing in life but, rather, "the payback of perseverance in the pursuit of a goal," a lesson she might have learned from the two black women she has made documentaries on. Lynch could easily have amended the brilliant title of her debut documentary, Chisholm '72: Unbought and Unbossed (2004) for, this, her second feature, because like Shirley Chisholm, another black woman who symbolized radical integrity, Angela Davis, was 'unbought and unbossed'. Davis shunned shabby compromise and resisted co-option as surely as Chisholm, the first black woman to run for President, did in the same era. Davis did so, too, when she stood ran as Vice-President on a Communist Party ticket at the start of the Reagan-Thatcher era. She has done so ever since. When running for office, both Chisholm and Davis conducted campaigns contemptuous of the calculated, focus-group-based electoral strategies of retail politicians and beyond the reach of corporate payola, campaigns of high principle designed to change the political agenda and raise fundamental questions about democracy. As Barrack Obama begins his second term, it's interesting and instructive to imagine him kicking back, after weeks on the campaign trail, to view Lynch's documentaries back-to-back. He might then meditate on the meaning of progressive politics, and say a little prayer for Shirley Chisholm and Angela Davis, two black women who helped clear the path to the White House for him.

Building on documentaries such as Yolande DuLuart's Angela Davis: Portrait of a Revolutionary (1972), Lee Lew-Lee's All Power to the People! The Black Panther Party and Beyond (1997), and Göran Olson's The Black Power Mixtape (2011), Shola Lynch has provided another riveting reminder of the Communist and honorary Black Panther whose name once appeared alongside that of fellow-traveller Bernadine Dohrn's on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted list. Where DuLuart offered a study in miniature, and Olson and Lew-Lee provided large canvass overviews, Lynch presents a year-in-the-life-of snapshot. In Free Angela and All Political Prisoners she, essentially, tells the gripping story of the event that catapulted Davis to fame in her late twenties: her trial, between 1970 and 1972, on charges of conspiracy, kidnapping and murder for her part in the abduction of Judge Harold Haley from Marin County Court in San Rafael, California.

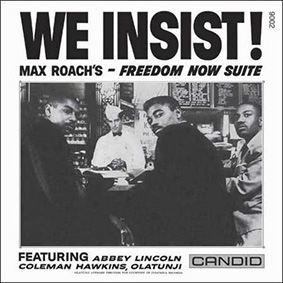

The events surrounding the attempted abduction and Davis's trial are covered in dazzling, dizzying detail. Lynch describes her film as "a political thriller', and thrilling it is. The events Lynch picks out of Davis's life are depicted with verve and vivacity. Finely judged editing by Lewis Erskine and Marion Monnier drives the film forward with fast-paced urgency. Erskine worked with Stanley Nelson on his documentary Jonestown: The Life and Death of People's Temple (2006) while Monnier worked with Olivier Assayas on his epic political thriller Carlos (2009); both bring their experience to bear with pulsating panache. Reviewing The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 I expressed my disappointment that the film's archive footage hadn't found its equal on the soundtrack. In Free Angela and All Political Prisoners that is not a problem. Just as Alex Gibney pulled off a masterstroke in Mea Maxima Culpa with his recording of deaf interviewees, so Lynch did when she lifted Abbey Lincoln's angry, anguished scream from Max Roach's jazz protest LP We Insist! and popped it into place in her film. It is an inspired choice. Lincoln's wired-up, wordless vocals fit that LP and this film perfectly. It makes for exciting, uneasy listening.

Despite its many virtues, Free Angela and All Political Prisoners fails to do its titular subject justice. Interviewed at the Toronto International Film Festival by Shadow and Act website, Lynch says: "You know the challenge in telling this story, where there are a million details related to both the crime and the trial and her politics, was to find a balance between what it is necessary to know and what you don't need to know. And what it is necessary to know is the stuff that allows the narrative to move forward and (the challenge is) not to leave out anything that is essential." The film stands and falls on the question of what Lynch regards as "necessary" and "essential,' and what she assumes "you don't need to know." For audiences with no prior knowledge of Angela Davis the film will, obviously, be a revelation, but Lynch doesn't tell us much about Davis that we didn't already know.

She mentions various aspects of Davis's life, in passing, but focuses on that headline grabbing 'story', to the exclusion of much that might have informed our understanding of Davis. She focuses on the abduction attempt and Davis's trial and passes over much that remains relevant to our times. Lynch's emphasis is on entertainment and narrative at the expense of education and ideas, which wouldn't be so damaging if Angela Davis were not living proof of the importance of education and ideas. Lynch's suspicion of ideas hit home when, after a Festival screening of her film, she described Davis as, 'a bit of a nerd'. In The Black Power Mixtape, Erkyah Badu, just before the Window Seat debacle, tells Göran Olson: "We have to tell the story right. And that's why black people have to document their own history, or history becomes twisted. We get written out." Sadly, placing black history in the hands of black directors is no guarantee of anything. The balance in Free Angela and All Political Prisoners is skewed in favour of 'the crime and the trial', narrative, and, astonishingly for a film about a significant political figure, politics. It is left to us to fill in the gaps and, as I do so below, I hope the film's flaws, and those of a certain tendency in contemporary documentary, will become apparent.

| From Birmingham to Berlin |

|

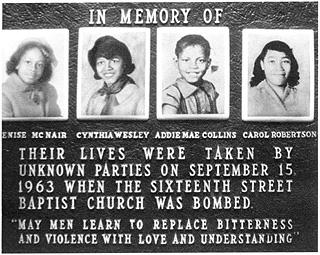

Now a Distinguished Professor Emerita, Angela Davis was always among the best minds of her generation. Like Bernadine Dohrn and Bill Ayers of The Weather Underground, she belonged to that wave of hyper-bright, highly educated middle-class radicals who 'could have had it all' but opted, instead, to dedicate their lives to political struggle. Where the motivation of most white revolutionaries was primarily ideological, Davis had additional personal reasons for revolt. She grew up with unhinged redneck racism in the Deep South, in Birmingham, Alabama; in the town nicknamed 'Bombingham,' and, specifically, in the neighbourhood nicknamed 'Dynamite Hill,' due to the dozens of bomb attacks aimed at the black community by the Klu Klux Klan. This was a town with a vicious, openly racist Chief of Police, Eugene 'Bull' Connor, a town that reacted to the Freedom Rides in 1960-61, and to Dr King's desegregation campaign in 1963, with more bombs. Davis's politics were shaped by the death, in the 1963 Baptist Church bombing, of four girls she knew personally.

These facts of Davis's early life help explain her passionate radicalism, as does the activism of her mother, Sallye Davis, a teacher and leading Civil Rights organiser. Davis grew up around the Communists with whom her mother worked to confront racism. By the time she left home in her late teens, having she secured a place at an integrated school in New York through the Quakers, she was already highly politicized. She soon joined the CP's youth wing, Advance, in which milieu she met red diaper baby Bettina Aptheka, who would later work for her defence in the Marin County Court trial at the heart of the film. Lynch withholds such information about Davis's childhood and adolescence for fear of scaring the horses, and, perhaps, herself. She is as excited by the seductive radical chic of Davis and the Black Panthers as she is alarmed by the realities of their 'actually existing' politics. Such is Lynch's disinterest in and distrust of radical politics, and her impatience to get to 'the story', that audiences are presented with a fully formed, ready-made revolutionary. We are left guessing about what lead Angela Davis to Communism (gullibility and naivety often offer themselves to the gullible and naïve as pre-prepared, uncritically absorbed answers to such questions). I'm no Communist but I cringe, nevertheless, at knee-jerk, force-fed anti-communism like Lynch's. Blind, obedient faith in free-market fundamentalism is the new Stalinism.

In Free Angela and All Political Prisoners, Shola Lynch largely ignores social and political context, thereby passing up an opportunity to clarify confusion surrounding the trial, Angela Davis, and the Black Panthers. Another key influence on Davis's political and philosophical allegiances is also relegated to the margins of the film: her encounter with the anti-fascist European left in France and Germany. Davis was already an ardent Francophile enamoured of Camus and Sartre when, in 1962 she headed for Paris on a Brandeis University scholarship grant. What she learned and saw in the city of light and, later, in Germany, informed her worldview as surely as her childhood experiences of racism and violence.

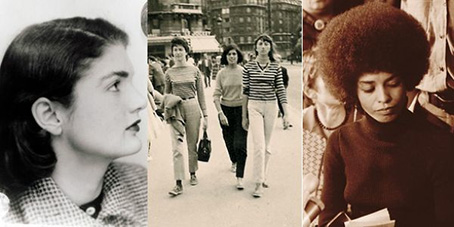

Left to right: Jackie Kennedy, Susan Sontag (centre), and Angela Davis

Angela Davis became an engagé Marxist intellectual after close-quarters contact with the French intellectual and revolutionary traditions, and, it has to be said, the anti-democratic outlook of the Parti communiste français. In France, she also saw racism anew, through different eyes. As Alice Kaplin points out in her latest book, Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag and Angela Davis, she arrived in the city of light to see "racist slogans scratched on the walls of the city proclaiming death to the Algerians." Paris had offered asylum to generations of African-American writers (James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright) and jazz musicians (Josephine Baker, Sidney Bechet, Dexter Gordon), but Davis immediately understood that she was, as a humble citizen, exempt from French racism only because it had other targets. In the mid-60s she moved to Frankfurt to study German Philosophy, where she was further politicized by her discovery of the Frankfurt School of Marxist theorists (Adorno, Horkenheimer but, particularly, Herbert Marcuse – who she studied and under whom she would later study). Many of the young Germans she lived with were confronting the Nazi past through New Left organisations such as the Sozialistische Bund (the Socialist League), the Sozialistische Deutsche Studentendbund (the Socialist Student League), and Rudi Dutschke's Subversive Aktion (provocatively and pointedly named in reference to the Nazi SA, the Sturm Abteilun). Davis cut her political teeth around these groups. It seems worth knowing if you want to know her.

* Ed Murrow’s speech from George Clooney’s Good Night and Good Luck

|