|

After a couple of years back in the US, during which time Angela Davis studied for her Masters under Herbert Marcuse, she returned to Germany to study for her PhD in philosophy. It is significant that she opted to attend Humbolt University in East Berlin. Humbolt, which was run by the Communist Party of the GDR – essentially as a factory for party cadres, was an institution that counted Hegel, Marcuse, Marx, Engels, Karl Liebknecht and William Du Bois among its alumni. It is hardly surprising that Angela Davis, more familiar than most with racism and repression in the US, already more familiar than most would want to be with Communist ideas, warmed so readily to a party and a country that welcomed her with open arms. Anyone baffled by Davis's decision to join the CP in 1968, at a time people were leaving it in droves and Soviet tanks were crushing the Prague Spring, might think this, also, worth including in Free Angela and All Political Prisoners. Sadly, Lynch is so intent on telling a story – and so keen to paint a sympathetic, sanitized portrait of her subject – that she ignores her contradictions and questionable choices. She, therefore, neglects to paint a portrait at all. The film is more a celebration of Davis than an examination, and, actually, more a single story even than a celebration. Despite having open access to Angela Davis, Lynch refrains from asking awkward or indelicate questions. It is clear she admires Davis, rightly so, but one wishes the film had probed as deeply as documentaries should do.

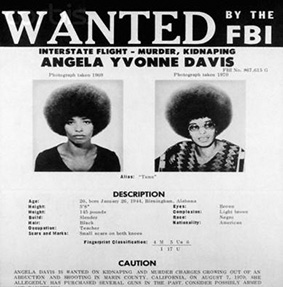

When she graduated in 1965 Angela Davis had joined the brightest of the bright, or what Du Bois called 'the talented tenth', as a worthy member of the elite Phi Beta Kappa Society (as had Francis Ford Coppola and Barack Obama Sr. before her and Terrence Malick would after her). The society's motto is: "Love of learning is the guide to life." An elite academic honours society founded in 1776, Phi Beta Kappa is committed to freedom of enquiry, thought and expression. Davis was called upon to defend those principles in 1969, when, soon after she began teaching at the University California, Los Angeles, she was on the end of an establishment witch hunt that ended in her expulsion from UCLA for her political convictions. Ronald Reagan, urged on by the FBI, persuaded the California Board of Regents to remove Davis from her post. Staunch defender of individual liberties that he was, Reagan called Davis's membership of the Communist Party a "provocation," though he later backed down and claimed it was Davis's "unprofessionalism" that prompted his anti-democratic move. A campaign to reinstate her was initially successful and she resumed teaching, but, in June 1970, she was again stood down. The UCLA debacle was headline news and it polarized opinion. Death threats and hatred directed against her increased a hundredfold. Just as the Black Panthers armed themselves to defend themselves and their communities in the face of police brutality and racist violence, so Davis was forced to arm herself for self-defence.

| Davis, George Jackson, and the Soledad Brothers |

|

Although unemployed after her dismissal from UCLA, Angela Davis was not inactive. She used her newfound fame to highlight injustice and her work with the Black Panthers kept her busy. In particular, she was involved in the campaigns to highlight the institutionalized racism of the prison system and to secure the release of George Jackson. In 1960, Jackson, who had just turned eighteen, was sentenced to 'one year to life' for driving the getaway car while a friend robbed a petrol station of seventy dollars. He had been advised to plead guilty in exchange for a lighter sentence. Jackson's friend was released in 1963, as Angela Davis settled into her studies in France, but Jackson remained locked up, in San Quentin and Soledad prisons, in appalling conditions, more often than not in solitary confinement. As successive parole boards rejected his appeals for release, Jackson was radicalized by his experiences, by extensive reading, and by the escalating racial tensions exploding across the US and inside the prison system. Jackson was still in prison ten years later when, in January 1970, three black inmates were shot dead by a prison guard during a fight between Black Panthers and the Ayran Brotherhood. After the guard was cleared on a verdict of 'justifiable homicide', another guard was killed in retaliation, and the Soledad Brothers (Jackson, John Cluchette, and Fleeta Drumgo) were charged with murder. George Jackson, nominally on a life sentence for his part in the theft of seventy dollars, now faced the death penalty. It is at this point that Free Angela and All Political Prisoners breaks stride, having reached its goal: the Marine County Court incident of August 1970.

Angela Davis was active in the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee. She believed, as did supporters such as Jean Genet and Michael Foucault, that the Soledad Brothers had been targeted for their militancy, and framed. Davis grew close to George Jackson and his family, including his 17-year old younger brother Jonathan, who had joined the Black Panthers soon after his brother. In a desperate attempt to secure freedom for the Soledad Brothers, Jonathan Jackson held up the Marin County Court while it was in session for the trial of James McClain, a black San Quentin inmate charged with stabbing a prison officer. Jackson handed guns to McClain and two other San Quentin inmates present as witnesses. Together, the four men tried to escape with Judge Harold Hayley and four hostages. As they left the building, police opened fire. Jonathan Jackson, the Judge, and two inmates were subsequently shot dead at a roadblock. The guns used in the abduction attempt were registered in Angela Davis's name and a warrant was issued for her arrest. With the FBI's Cointelpro campaign of political assassinations and intimidation at its height, and in an atmosphere of widespread distrust of the political establishment, Davis fled California. She was on the run for two months. She was placed on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted list and, after a nationwide woman hunt, eventually apprehended in a New York motel in October 1970.

| The Trials of Angela Davis |

|

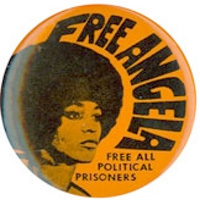

During the 18 months that Angela Davis was subsequently held in prison pending trial, an international campaign to free her gathered momentum. Solidarity committees were formed across the US and thousands marched for her release, with particularly high turnouts in France and the GDR Her case offered the defeated left and the Black Panthers a rallying point. It also touched a nerve with politically non-aligned citizens who felt Davis was being prosecuted for her political convictions and saw her trial as a stand for freedom of speech and thought. In 1972, a Californian diary farmer, Robert McAfee, put up his farm as collateral towards Davis's bail. Lynch includes a riveting clip of McAfee talking to camera. It is a moment typical of the way the film gallops towards its story, leaving us feeling short-changed. Where the facts of the trial are concerned, once again, we're left wanting more. The prosecution's case was based on Davis's provision of the firearms used in the abduction attempt. It might have been worth pressing Angela Davis on that point, now it is no longer sub judice. I'm no lawyer, and I may be naïve, but surely, if only for reasons of political expediency, the case is now well and truly closed. The prosecution also made much of Davis's relationship with George Jackson, implying that a romantic attachment on her part might have prompted her to act as part of a conspiracy, but succeeded only in 'proving' that she loved him.

In August 1971, while Angela Davis languished in prison, George Jackson was shot dead during an alleged escape attempt. Jackson's death triggered the Attica prison riots (cited by Sidney Lumet in Dog Day Afternoon) and added to the widespread sense of anger still raw after the assassinations of Dr King, Bobby Kennedy, Fred Hampton, and others. James Baldwin said: "No Black person will ever believe that George Jackson died the way they tell us he did." Lynch avoids that question. She avoids as many questions as she raises. That's her directorial choice, her right if you like, but it is curious that, while she suggests that Davis and Jackson's relationship went beyond that of platonic comradeship, she doesn't broach the issue with Davis. She lasciviously dwells on the sensuality of their encounters in jail, but asks Davis no direct questions about her relationship with George Jackson. Facing a possible death sentence, grieving over the death of the man she loved, Davis's time in prison must have been traumatic, and she must think about him to this day. It would be understandable, even admirable, therefore, if Lynch refrained from indelicate questioning about Angela Davis's relationship with Jackson in order to respect her privacy and protect her feelings. Sadly, there are worrying signs in the film that Lynch's own relationship to Davis was too close for comfort.

After a Festival screening of the film at The Ritzy in Brixton, Lynch amusingly called for probing questions from "All you Brixtonians," then let slip a suggestion that Davis's contribution to the film might have amounted to a controlling interest. Lynch alluded to three separate, revised contracts agreed with her subject during production. She has talked elsewhere about her tussles with Davis over the film's title, and I would bet my bottom dollar that Davis insisted on the inclusion of the words " . . . and All Political Prisoners." The mutual respect and affection that Davis and Lynch feel for one another is a joy to behold. They might be mother and daughter. Such a close relationship, however, exposes the film's lack of objectivity. Lynch is on record as a believer in the importance of objectivity in documentaries. I'm not myself; claims to objectivity have always been used as a stick to beat dissident directors. As Emilio de Antonio, said, "Honesty and objectivity are not the same thing. Nor are they even closely related."

© Roz Payne/Newsreel Collective

At one point in No, the final film in Pablo Larraín's magnificent Pinochet Trilogy, ad man René Saavedra, as played by Gael García Bernal, looks on as state police clash with left-wing activists crying, "Free all political prisoners." No such cries are heard in Shola Lynch's film. If women are 'the presence of an absence' in Alex Gibney's Mea Maxima Culpa, political prisoners are in Free Angela and All Political Prisoners. After that Festival screening, I asked Lynch about that absence, as I'd asked Claude Lanzmann about the absences in his. She simply smiled and shrugged her shoulders. Shola Lynch is as charming, polite, and impressively energetic as Alex Gibney, which may explain what's lacking in their films: a sense of combative anger. Angela Davis has spent her life fighting for the abolition of prisons and founded the prison abolition campaign, Critical Resistance. In her book Are Prisons Obsolete? she argues that imprisonment is used as a means of social control underscored by racism and the profit motive. To blank out Davis's entire life since the early 1970's, to evade the question of political prisoners, as Lynch does in her film, is part of that retreat from politics discussed above.

It is both shocking and revealing that Lynch doesn't address an issue of such importance to her subject and to African Americans. A documentary cannot say everything, but it's revealing what directors choose to leave out. In his introduction to Jackson's prison letter, Soledad Brother, Jean Genet wrote: "Racism is scattered, diffused throughout the whole of America, grim, underhanded, hypocritical, arrogant. There is one place where we might think it would cease, but on the contrary, it is in this place that it reaches its cruelest pitch, intensifying every second, preying upon body and soul; it is in this place that racism becomes a kind of concentration of racism: in the American prisons." Michael Foucault regarded the black liberation struggle inside US prisons as a new revolutionary front. At a press conference Chapelle SaintBernard in February 1971, he said: "They tell us that the courts are swamped. We can see that. But what if it were the police who had swamped them? They tell us that the prisons are overpopulated. But what if it were the population that were being over-imprisoned?"

Today, there are over one million African Americans prisoners within a prison population of 2.3 million. There are 4,575 prisons in operation in the US, more than four times the number of second-placed country, Russia, which has 1,029 prisons. As Christian Parenti points out in his seminal book on the prison industrial complex, Lockdown America: Police and Prisons in an Age of Crisis, the land of the free deprives more of its fellow citizens of their freedom than any other country in the history of humankind. It is an issue addressed by Eugene Jarecki in his new documentary, The House I Live In, which I'll review shortly. Jarecki dissembles the US 'War on Drugs' and shows how that cynically calculated campaign swells prison numbers. Eugene Jarecki is among the most important and gutsy documentary filmmakers working today. In Why We Fight he took on the military industrial complex. In The House I Live In he tackles the prison industrial complex and the war on drugs.

Those hoping Shola Lynch passed over the pressing issue of prisons and prisoners because she intends to return to it in depth at a later date are likely to be disappointed. I cannot imagine her deciding to focus her considerable energies on political prisoners in Chile, China, Egypt, Ireland, Russia, Syria, the US, or anywhere else come to that. Those hoping that she will return to Shirley Chisholm and Angela Davis in order to delve deeper into the political context of their lives are, likewise, likely to be disappointed. Lynch says: "What I'd love to be able to do is either produce or direct the narrative versions. I think there's room to do the documentaries, to do the research and provide the information for scripting . . . But then, wouldn't it be great – because we'd reach an even wider audience – to do narrative versions? I mean they're fantastic stories." At last year's London Film Festival, I compared Angela Davis to Bernadette Devlin while reviewing Göran Olson's The Black Power Mixtape back-to-back with Leila Doolan's fine film on Devlin, Bernadette: Notes on a Political Journey. With my heart in my mouth, I reported that a 'narrative version' of Devlin's life, with the working title 'Roaring Girl', was in development. It was set to 'star' Sally Hawkins of Happy Go Lucky fame. Bernadette Devlin said: "The whole concept is abhorrent to me. How dare they make a pretend life for me while I'm still living the real one?" At the time, she was fighting the proposed film in the courts. In May, Intandem Films PLC (which describes itself as an organisation split into "four business segments: film sales, executive producer fees, sales commissions, and recoverable project costs," whose "subsidiaries include Intandem Pictures Ltd, Intandem Entertainment Ltd, and Intandem Film Fund 1 LLC") announced it had been appointed to sell the film. It will be called 'Devlin' and is in production. The heart sinks. It sinks lower still at the idea that, sometime soon, we might be reviewing 'Devlin' alongside, 'Davis' starring, say, Janet Jackson or Pam Griers as Angela Davis.

Of all the films I saw at this year's Festival, the one most surely crying out to be made as a documentary was Craig Zobel's Compliance. The opening title card declares it to be "Inspired by true events." The 'true' events in question are the 70 cases in which malicious callers have convinced the management and staff of fast food outlets across the US that they represent authority figures such as the police, and then successfully ordered them to sexually abuse female staff. Zobel takes one such colossal deception, which occurred at a McDonald's n Mount Washington, Kentucky in 2004, and makes a story out of it. I have seldom been so excited at the prospect of seeing a film, or as disappointed and disgusted in what I saw. Zobel and his producers take an important idea and exploit it for commercial gain and sexist sexual titillation. Compliance instantly recalls Stanley Milgram's famous 1963 experiment in social psychology, obedience, conformity, and the power of authority. Milgram monitored the reaction of randomly selected volunteers to inflict pain or death, by electric shock, upon actors in another room if they failed to answer a series of questions correctly. 65 per cent of those sampled continued to apply shocks despite the screams and protest of a fellow human being, beyond the point that the screams stopped. In Zobel's film the victim, Becky (played by blonde, beautiful, shapely Dreama Walker), is strip searched and persuaded to perform sexual acts by men who are 'just following orders'.

It hardly needs saying that a documentary that investigated all 70 cases, or even one, would generate considerable public debate on the significant questions raised. Zobel doesn't shy away from showing the actress strip but he does shy away from the social and political implications of the case. Reviewing the film in Cineaste, Robert Koehler says: "Although the project reflects Zobel's thorough research of the case, the film's essence doesn't lie in its journalistic integrity, its adherence to facts, or its research propriety – all of those tired yet widely respected notions of what lends supposed credibility to the incredible tale, the branded assuredness of 'the true story'. This is just the lure, for those audiences allowing themselves to be hoodwinked by the absurd reasoning that if a movie is based on actual events, it must be truer than those that aren't. No, Zobel knows this is the honey to draw those and other audiences toward this show." In the context of what I've already said above, I hope I can leave Koehler's comments to speak for themselves.

Much I've said above was generated by my troubled doubts about the motives Gibney, Lynch and Zobel had for making their films. When someone in the audience at the Festival screening of Free Angela and All Political Prisoners asked Shola Lynch what prompted her to make a film about Angela Davis, she replied: "I wanted to know who she was, this woman in the funky afro." John Grierson saw documentaries as an essential aspect of education, and education as an instrument of social change "not dreaming in an ivory tower, but outside, on the barricades of social construction, holding citizens to the common purpose their generation has set for them. Education is activist or it is nothing." Documentaries made by directors enraged by things they found in the world, who had to make films to unburden themselves of outrage and in an attempt to achieve change, will inevitably be more charged than those who parachute into a given subject, problem, or question as a job of work, then scamper off to their next project. Nobody wants to watch endless agit-prop but we recognise the ring of truth in documentaries made by directors who 'live' their subjects, and the off-key notes of those that don't. Anybody wanting to delve deeper into Angela Davis and the Black Panthers than Lynch's film does will understand all if they watch the Newsreel Collectives films, Off the Pig, Mayday and Repression, recently gathered together as a DVD compilation, What We Want, What We Believe. The activist group was on the ground, in the action, and in the know – in ways that only activist filmmakers can be.

A couple of nights ago, I was at Tate Modern to watch a riveting documentary double bill: William Klein's contribution to the anti-war anthology film, Loin du Viêtnam/Far From Vietnam, (1967), and his biopic Elridge Cleaver, Black Panther (1970). Klein's film on Cleaver derives its force from its director's prowling camera and curiosity, Cleaver's charisma and confusions, and the sense the film emits of Algeria as an epicentre of international revolution, rather than the sense of political purpose that motivated Cleaver and Klein, at that precise moment. We don't get much more political context in Klein's film than we do in Free Angela and All Political Prisoners, but then Klein was addressing contemporaries familiar with that context. What we get is Cleaver up-close, in his own words. Klein has always been more interested in how people look and act than ideas and information. Despite being seduced by the insurgent energies of the Black Panthers and the New Left, Klein's curiosity is largely restricted to images. In his contribution to Loin du Viêtnam/Far From Vietnam, (1967), Klein focuses, instead, on faces at demos, on the stories of Norman Morrison (the Quaker who doused himself with petrol and burned himself to death in front of Robert McNamara's Pentagon office in 1965 to protest the war), and that of his widow, Anne Morrison, the embodiment of serene stoicism. For this film Klein tapped into the archives of the activist Newsreel Collective. Alain Resnais said of the film: "Far from Vietnam is a film of question marks, of questions we ask ourselves as often perhaps as you. It's for that reason that we put them on the screen: after all, it is as natural for filmmakers to speak on a white canvas as in a café." That's what documentaries are: question marks.

Despite the magnificent contributions of Ivens, Klein, Lelouch, Resnais, Godard, and Varda, Loin du Viêtnam/Far From Vietnam it is Chris Marker's editing skills and activist commitment that holds it all together. It was Marker who mobilised over 200 technicians, cinematographers, editors, runners and so on. It was Marker who kept them at work for four months until the film was finished. In his 1968 Sight & Sound review of the film, David Wilson says: "Far From Vietnam may be hailed as the most important event of the 1967 London Film Festival, just as two years ago Kenneth Tynan said about The War Game that it may be the most important film ever made . . .The importance of (the film) is that it is not a propagandist film. For a collective effort it has a remarkable sense of shape . . . What one is aware of is an examination of 'Vietnam' with all the undercurrents of that emotive word, involving us at a far deeper level than propaganda. By doing so, it forces us into a dialogue with ourselves." That's what the best documentaries do; they force us to think through our own paradoxes, perspectives, philosophies, prejudices and partisan positions; and it's engaged, activist documentaries that do that best. Nobody did that more than Emilio de Antonio. The documentary that most excited me at the 2011 London Film Festival was de Antonio's anti-McCarthy film Point of Order (1964). The documentary that most excited me at the 2012 London Film Festival was de Antonio's In the Year of the Pig (1968).

De Antonio was the epitome of the activist documentary filmmaker. His filmmaking practice, which he called "democratic didactism" and which relied on "radical scavenging," was like a cinematic version of William Burroughs's literary 'cut and paste' techniques. It combined ideas and information, radical quotation and montage to powerful effect. He wore his heart on his sleeve, advocating bias and the honest presentation of up-front argument. His aim was not to teach but to reveal. Introducing the Festival screening of In the Year of the Pig, the estimable Clyde Jeavons, who programmes the Festival's Treasures section, announced that, unusually, this film hadn't been restored. Ross Lipman, of the UCLA Film & TV archive, had been told by de Antonio's daughter, Nancy, that it was not to be 'cleaned up', in honour of her father's radical aesthetics and in keeping with his belief that great films don't look pretty. I relished every crackle and grainy blotch. While de Antonio's made memorable films that stand at the pinnacle of documentary filmmaking, we must bracket those of Alex Gibney and Shola Lynch in the category described by Jean-Louis Comolli & Jean Narboni in Cahiers du cinéma as containing "films which have an explicitly political content . . . but which do not effectively criticize the ideological system in which they are embedded because they unquestioningly adopt its language and its imagery."

I will leave the last, seemingly gloomy but ultimately optimistic, word to that most fluent and fluid of writers, James Agee. Agee was no lover of documentary. He believed that film should work for, and through, the eyes not the mind or, even, the heart, but he was one of the most perceptive critics of his era. Toward the end of a life spent reviewing films, a life that incidentally produced one of the great books of the 20th Century, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee wrote: "Most movies are made in the evident assumption that the audience is passive and wants to remain passive; every effort is made to do all the work – the seeing, the explaining, the understanding, even the feeling . . . but pictures are not acts of seduction or benign enslavement but of liberation, and they require, of anyone who enjoys them, the responsibilities of liberty. They continually open the eye, they awaken curiosity and intelligence." Elsewhere, he says: "I am forced, more and more, to the dull, narrow hope that if good movies are to be made at all any more . . . they will have to be made on shoestrings, far outside the industry, and very likely by amateurs, or at best by semi-professionals."

|