| The British Establishment: Sex, Lies, and Hypocrisy |

|

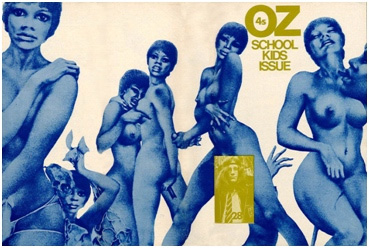

Geoffrey Robertson's exemplary career as a lawyer and public figure draws attention to historic aspects of institutional hypocrisy almost as shocking as those revisited in Mea Maxima Culpa. Robertson cut his legal teeth, as an enthusiastic young barrister assisting the late John Mortimer's landmark defence of free speech and the counter-cultural values of the 60s, in the 1971 Oz obscenity trial – then the longest running, most expensive obscenity trial in British history. The publishers of Oz, a magazine that challenged the sexual repression and hypocrisies of 'straight' society, stood accused of "intent to debauch and corrupt the morals of children and other young people" – at a time when priests and other adults were routinely abusing "children and other young people," safe in the knowledge that retribution would be slow in coming, if it came at all. Discussing the Obscene Publications Squad, a police protection racket in operation at the time of the Oz trial, Robertson says: "There was the extraordinary irony that some of the police who were going to battle against the underground press on the basis that it was endangering their children were those who were allowing pornography of the most ugly, desolating kind to flourish in Soho."

At the Q&A after the screening of Mea Maxima Culpa I attended, someone asked Alex Gibney if he'd heard of the case of 'much-loved' British entertainer Jimmy Savile, whose paedophile activities over decades are only now coming to light, a year after his death. Gibney hadn't heard of Savile's abhorrent behavior; nor had the British public until a few months ago. It was, we now learn, an open secret in establishment circles. I recently had a sideswipe at Andrew O'Hagan for the disingenuous arguments he deployed to justify his retirement as the Daily Telegraph's 'film critic'. I now call him as a witness for the prosecution in the case of establishment hypocrisy. In an article titled 'Light Entertainment' (London Review of Books, 8 November), he says: "If you grew up during 'the golden era of British television', the 1970's, when light entertainment was tapping deep into the national unconscious, particularly the more perverted parts, you got used to grown-men like Rod Hull clowning around on stage with girls like Lena Zavaroni." The paedophile crimes of Jimmy Savile and pop star Gary Glitter, and subsequent arrests of comedian Freddie Starr and Radio One DJ Dave Lee Travis (a.k.a. ‘Hairy Cornflake’), were conducted within a sexist culture that sexualizes the young, and the very young, in a culture that turns a blind eye to numerous crimes. Andrew O'Hagan notes that a well-researched BBC Newsnight investigation into the Savile case was shelved in favour of two pre-prepared BBC tributes to Savile. O'Hagan also talks about Dan Davis, who had been working on a biography of Jimmy Savile for several years: "He always said the story was seedy and strange and that when the book was published he would call it Apocalypse Now Then." Davis's book remains unpublished.

Shocking as these revelations and those repeated in Mea Maxima Culpa are, it is appalling that hardly anybody investigated these matters at the time. We need effective investigative journalism and, particularly when that is in such short supply, we need a fearless independent documentary culture. With yellow journalists and the Forth Estate increasingly intimidated, if not pocketed by corporate power; with a pervasive culture of self-censorship helping to render the cross-examination of power ineffective, inept or invisible; we need punchy documentaries more than ever; with the mainstream media increasingly functioning as a monolithic propaganda machine for power, we now need punchy documentaries more than ever. We need them as an escape route from escapism, because they help us make sense of a complex world, and because they address the democratic deficit. Recent scandals in the City, at the BBC, and within the Palace of Westminster, reveal an establishment rotten to the core. The Eleveden, Hillsborough, and Leveson inquiries into police and press lies; the FSA reports on corruption at Barclays, RBS, and Standard Life; the revelations about paedophilia at the BBC, in the Catholic Church, and in North Wales care homes; the ongoing scandals around MP's expenses – it all points to the establishment's arrogance and greed while begging the old question, "Who guards the guardians?" It highlights a decline in public conversation and the mechanisms of public accountability, and a concomitant contempt for the public and the idea of public service. It highlights, too, the crying need for an inquisitive, inquisitorial documentary film culture as a combative counterbalance to spurious notions of 'objectivity'.

There were few documentaries in sight in Sight & Sound's recent list of 'The Greatest Films of All Time'. Godard's L'Histoire(s) du cinéma, Mikhail Kalatozov's I am Cuba, Claude Lanzmann's Shoah, and Dziga Vertov's seminal Chelovek s kinoapparatom/Man With a Movie Camera all featured, as you'd hope. Mentions for Tomás Gutíerrez Alea's Memories of Underdevelopment and Pino Solanas's La Hora de los Hornas/The Hour of the Furnaces indicate that Third Cinema hasn't been entirely forgotten, and Humphrey Jennings' Listen to Britain is there to keep the memory of the British Documentary Movement alive. Chris Marker, Patricio Guzmán and Godfrey Reggio get passing mentions too, but that's about it. Not a single documentarian made the Top 25 list of directors in the poll.

Fortunately, the picture for documentary film culture isn't as bleak as that hideously riveting Sight & Sound poll suggests. Despite having listed from a list, I'm generally as suspicious of official lists as I am of official versions of history. Lists can be useful though, particularly those that prove the fatuousness of other lists; one such is provided by Films for Action, their list of 100 World Changing documentaries.* I confess I've only seen a fifth of their selected films, but, to pick out a few gems: Jennifer Abbot and Mark Achbar's The Corporation, Eugene Jurecki's Why We Fight, Robert Kenner's Food Inc, Robert McChesney's Rich Media, Poor Democracy, and John Pilger's The War on Democracy would, taken together, be sufficient to reshape most people's view of the world. Well-researched documentaries that challenge the status quo are there waiting for those prepared to look for them. It's a question of making the time to do so. It's a matter, too, of what, and whether or not, we're informed about films that would inform us.

Films for Action's mission statement offers a useful summary of the reasons documentaries matter. In order to foreground the background to all discussions of documentary, it's worth returning to basic principles and restating the unfashionable views that the censorious, homogenizing tendency of corporate power is bad for our cultural and political health; that the free flow of information and ideas essential to free societies is staunched by commerce; that a vibrant, independent documentary film culture leads to a more effective cross-examination of power; and that documentaries, of all kinds and intentions, lead to a better informed, more politically conscious citizenry. Welcome initiatives such as Films for Action, and the documentaries they recommend, help fill a vacuum in the distribution of information and, as such are a vital part of democratic participation. That wise warhorse of the Left, Tony Benn, distilled a lifetime of accumulated knowledge into a series of democratic questions we should always ask of the powerful: "What power have you got? Where did you get it from? In whose interest do you exercise it? To whom are you accountable? How do we get rid of you?" Arnold Wesker put it more bluntly in an introduction to his play Chips With Everything: "The battle is between those who ask questions and those who don't want questions to be asked." Documentaries ask questions on our behalf. When we feel documentaries are being undervalued and marginalized, we might think of those who benefit from that.

Documentaries question but they also explain. As Peter Wollen says: "Truth has no meaning, unless it has explanatory force, unless it is knowledge, a product of thought. Different people may experience the fact of poverty, but can attribute to it all kinds of different causes: the will of god, bad luck, natural death, capitalism. They all have a genuine experience of poverty, but what they know about it is completely different." In the absence of explanation and information we become confused. Time after time lately the cross-examination of power has been revealed to be ineffective, inept and insufficiently courageous. By way of contrast, in 1947, in the first issue of the short-lived Informational Film Year Book, Norman Wilson says: "It should be the aim of everyone who believes in democracy to make the freedom of the screen as much a reality as the freedom of the press." This is a good time to consider documentary. For those who've followed me this far, I'd like to return, briefly, to my colleague's chair and consider what we're sitting on when we watch documentaries like Alex Gibney's and Shola Lynch's. Or, better say, I'd like to step out of the chair, stand back, look at where it sits in the wider room and wonder how it got there.

| Grierson and the Founding Fathers |

|

Anyone who has consistently argued that unpleasant facts should be served straight, no-chaser will be familiar with a set of stock responses: you will have been told to 'lighten up', maybe to 'put up or shut up', you will probably, at some point, have been accused of killjoy Puritanism. You may bristle, but you learn to shrug off such censorious refrains and ask for arguments instead of airy Panglossian invective. The shrill enquiry, "Anyway, what's so wrong with a bit of entertainment?" usually arrives as an afterthought that at least implies an open-minded interest in ideas. Pick your own answer, I usually fight vagueness with vagueness and say, "Nothing, but there's a time and place for everything. There's a time and a place for stories, but it's not in documentaries." Documentaries help us to rethink our place in the world in different ways. They provide us with the information, ideas and hard facts we need in order to make informed decisions and hard choices. They satisfy our urge to know. They bring us down to earth. They get us talking and thinking as few other forms. They can even motivate us to act, enraging us to a point where we feel forced to confront injustice when we learn of it.

In a note on John Grierson that appears on the Grierson Trust's own website, John Chittock, says: "If the role of the moving picture in society today has succumbed to becoming chewing gum for the masses, it is because the world has no real successors to the likes of Grierson and his colleagues." I'd propose Patricio Guzmán, that doughty Chilean champion of non-fiction film, as a worthy successor to Grierson, but I share Chittock's sentiments. One can no more imagine John Grierson arguing for documentaries as a form of entertainment than one can picture his reaction to a film about child sexual abuse in the Catholic Church, straight-backed embodiment of Calvinist rectitude that he was. Grierson's faith in facts was inextricable from his faith in the possibilities of radical political transformation, and in his audiences. Grierson saw film as means towards an end, namely, the creation of a healthy democracy and an informed citizenry. He stressed the Documentary Movement's sense of educational mission and its social motives. He was a missionary with a movie camera who viewed cinema as a pulpit. His ethos was shared by most of the young directors he nurtured. As Lindsay Anderson noted, Grierson was proud that "the group was inspired, not by the fiction and the romance of the movies, but by the romance of social advance, community, and the technological society."

The world has changed since Grierson's day. Television has arrived, for starters. Yet, documentaries still reflect the zeitgeist, or, to put it another way, the dominant ideology. Grierson, Jennings et al. were driven by a shared sense of social purpose and supported by the commonwealth: Alex Gibney and Shola Lynch operate in an atomized culture obsessed with money, one that places commercial and entertainment values at the heart of our culture. To put it even more crudely, hedonism and fiction films are fashionable; education and factual films are not. David Hare wrote in The Guardian: "Of course, you must expect it, in rightwing times, rightwing art flourishes." Well, Grierson and his disciples were shaping documentary during rightwing times too, in an era when democracy was floundering, unemployment was high, and fascism was rising. Crucially, though, the 30's and 40's were also a time of great competing hopes and active resistance; an era in which respect for education was crystallised in organizations such as the BFI, the WEA, and, ultimately, the comprehensive education system; a time, too, when faith in social progress and the 'good society' was embodied in the welfare state in the UK and the WPA in the US.

That shared sense of public purpose and the public good, far from encouraging formulaic filmmaking practices, generated increasingly daring formal innovation. That daring is most evident in the work of Humphrey Jennings, particularly in his masterpiece Listen to Britain, which, with its lyricism and hypnotic rhythms, demonstrates the exhilarating heights documentary can rise to when it lets associative ideas, images, sounds, and facts speak for themselves. The Documentary Movement may have been as one in their ardent desire to educate and inform, and their associated belief in political change, but they developed conflicting approaches to the form they formed. As they invented on the hoof, the directors Grierson nurtured veered off the course he'd set them on. He must have thought he'd created a Frankenstein's monster when he saw the gradual integration of 'informational films' and 'story-films'. He must have seen it coming and it might, perhaps, have informed his decision to follow the geese to Canada in 1938. While he was there, creating what was to become the National Film Board of Canada, the world's greatest monument to the documentary form, the 'wartime marriage' of documentary and fiction was gathering pace. In his definitive study, Humphrey Jennings, Keith Beattie notes Andrew Higson's argument that the fusion of fictional and documentary practice in the story-documentary was at the heart of Britain's contribution to wartime and post-war cinema. Beattie also mentions James Chapman's description of the fiction-documentary formula as "the characteristic mode of representation in most 1950's war films." Chapman cites The Colditz Story (1950), The Wooden Horse (1950), and The Dam Busters (1958) to make his point.

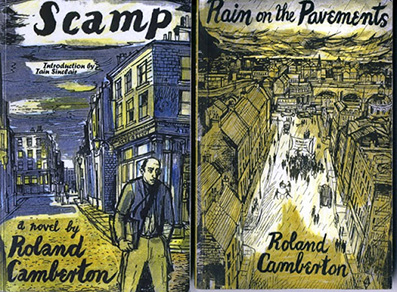

As I began to piece together these thoughts on Grierson and documentary, something beautiful happened, one of those coincidences so loved by Humphrey Jennings. My friend, Sydney Davies, and his partner, Jules Lyne, called round bearing gifts that made my heart race: boxes packed with film journals, including first edition copies of Sight & Sound from 1932 to 1968, and first edition copies of books such as Forsyth Hardy's indispensable anthology Grierson on Documentary, Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach's 1938 Histoire du Cinema, and Pudovkin's works on Film Technique and Film Acting. [This cinephile treasure trove was part of the legacy left by Jules's father, Douglas Lyne, MA Oxon, who died in 2010. A veteran of the battles of El Alamein and Monte Cassino, Douglas devoted much of his life to "taking war off the menu of mankind" through organisations like the Monte Cassino Federation of Remembrance and Reconciliation. After helping to liberate Rome, he returned to Civvy Street to work in theatre, documentary and PR. In the bohemian Soho of the post-war years, Douglas mixed with filmmakers like Paul Rotha and writers like his friend Henry Cohen, a.k.a. Roland Camberton. I have Douglas's insatiable curiosity and love of cinema to thank for an incredible collection of books; the world can thank him, in a roundabout way, for the belated reappearance of two 'lost' London novels of the 50's: Roland Camberton's Scamp and Rain on the Pavement. Author and filmmaker Iain Sinclair had been trying to trace Camberton ever since reading the vanished writer's work 30 years earlier. He had drawn a blank, until he read about a meeting between Douglas, William Burroughs and Roland Camberton in my friend Syd's book, Walking the London Scene: Five Walks in the Footsteps of the Beat Generation. Sinclair contacted Syd immediately, Syd introduced Sinclair to Douglas, they discussed Burroughs and Camberton, Sinclair turned their conversation into an article on Camberton for The Guardian, and that lead, eventually, to a reprint of the novels. Thank you Douglas.].

| An Instrument of Public Thinking |

|

Rummaging excitedly through my boxes, and reading through its contents in the interim, the contrast between post-war optimism and present-day cynicism struck me forcibly, as did the distance film has come since its studio-bound days. Back in the 30s and 40s the battle lines were clearly drawn. I could quote from the books in those boxes all day. In First Principles of Documentary, Grierson says: "We believe that the cinema's capacity for getting around, for observing and selecting from life itself, can be exploited in a new and vital form. The studio films largely ignore this possibility . . . documentaries can achieve an intimacy of knowledge and effect impossible to the shim-sham mechanisms of the studio and the lily-fingered interpretations of the metropolitan actor. . . There is nothing to prevent the studios going really high in the manner of theatre or the manner of fairy tale. . . I make this distinction to the point of asserting that the young director cannot, in nature, go documentary and go studio both." Grierson's comments are drenched in disdain for the studios and contain an echo of Vertov's battle cry: "Down with bourgeois fairytale scenarios . . . Long live life as it is!"

Once cinema had broken out of imprisoning studios, all films became documentaries of a sort. It is no wonder that the pioneers of documentary honoured the debt they owed to those of their antecedents who challenged the studio-bound cinema. My jaw dropped when I found, in one of my lovely Lyne boxes, an illustrated appreciation of Eisenstein, published to mark the director's death in 1948. Other than Pudovkin, no director had as marked an influence on the founders of documentary as Eisenstein. Pudovkin and Eisenstein: the song and the scream. Grierson and Rotha saw documentary differently but they would both have approved of Eisenstein's view that film should plough the audience's psyche. In the magazine's introductory encomium, Paul Rotha says: "Eisenstein used his camera like a marksman uses his rifle . . . With Kuleshov and Pudovkin, he seems the first director after Griffith to understand the time-space flexibility of the film medium . . . How much of today's shooting, rigidly held to the script page, so many shots an hour, so much completed film shot in a day, has that spontaneous vitality which makes the work of Eisenstein and Flaherty alive today?" Elsewhere in the magazine, John Grierson says: "Eisenstein was not a poet like Pudovkin . . . nor a finely tuned descriptive director like Flaherty . . . His raw material was documentary, and it was in this connection with his work and with Flaherty's that we first coined the term 'documentary' and put it into circulation . . . I speak personally and with some emotion, but perhaps I can say nothing more profoundly grateful in homage to Eisenstein than that he was our guide and teacher in the early days when we were developing our own domestic cinema into an instrument of public thinking."

In Sight & Sound Vol. 1. No. 2. Summer 1932, beneath an editorial advocating the establishment of a National Film Institute, the Director-General of the BBC, John Reith, says: "I should like to wish every success to SIGHT AND SOUND. It is of supreme importance that in the exploitation of applied science the single aim of the advancement of culture and intellectual standards should be recognised as an ideal by us all." The same emphasis on education and respect for learning is evident in the magazine's description of itself as "A Quarterly Review of Modern Aids to Learning Published Under The Auspices of The British Institute of Adult Education." It is evident, too, in an equally earnest welcome for the magazine, not from a commercial sponsor, though the magazine opens to 14 pages of ads, but from Ernest Barker, Professor of Political Science, Cambridge. Mr Barker says: "There is only one danger about these "modern aids to learning': but is so obvious to us all that I am sure we shall all avoid it. It is so easy to sit, and just see and hear; but real learning and teaching are never too easy, because they both involve a painful effort of the mind and a genuine 'discipline'." How times have changed. We say 'documentarian' where they said 'documentalist', we say "narrative' where they said 'story-film', we say 'propaganda' where they said 'public relations', we say 'me' where they said 'we'.

| Television and Documentary |

|

How did we get here from there? How did we get from John Grierson to Simon Callow, from Clement Attlee to Margaret Thatcher, from Humphrey Jennings to Sam Mendes? Public ownership arrived, then privatization; the Eady Levy, then a commercial free-for-all-who-could-afford-it in television, then home entertainment platforms. It's hard to pin down the ways the political shift to right since the 1970's have affected culture. All that is solid melts into air. The dominant ideology has crept over and seeped into our culture like a fetid fog, bearing within its masking mist a myopic cynicism. Out of that clammy haze loom the indefinite shapes of 'dumbing down' and 'entertaining up'. It's hard to discern where those processes came from and how they move, but they're there all right. In keeping with La Thatcher's belief that there is no such thing as society and the prevailing view that industries (unlike banks!) should sink or swim in a storm-tossed marketplace, successive Thatcherite governments, to this day, have treated culture as a branch of commerce. The influence of television on documentary is too vast a field of enquiry to cover here, but, in order to make any kind of sense of it, we should skim two significant Thatcherite interventions in audio-visual culture: the abolition of the Eady Levy in 1984, and the 1990 Broadcasting Act.

First proposed by Harold Wilson in 1940, when he was President of the Board of Trade, the Eady Levy (named after its architect, the Treasury mandarin Wilfred Eady), provided a form of subsidy to producers of British films as part of an attempt to tackle the monopolistic practice of 'vertical integration' (the ownership of the means of production, distribution and exhibition by the same companies). The levy pooled a proportion of UK box office revenue, with half being retained by exhibitors and half divided among qualifying 'British' films. It was also part of an attempt to address the perennial problem of the ability of European films to compete with Hollywood; because the European market is comparatively small, they have tended, and tend, to be made with America in mind and/or with American money. Ironically, the concession made it possible for foreign film companies to write off a significant proportion of their production costs by filming here and had attracted filmmakers such as Antonioni, Polanski and Kubrick here. The levy did much to buoy up the film industry in the 60's and 70's, and its abolition inaugurated a downward trend in self-financing British film: with Eady gone many studios closed or concentrated on TV work. This process, combined with the 1980 and 1989 crises in the film industry, lead to a panicked search for exportable images and copycat commissioning, to the detriment of documentary. The big money, the American money, felt what British cinema did best was literary adaptation, historical drama, and romantic comedy.

The shift in power and resources from film to television may have been forced upon those involved but it had a partially positive outcome in that it concentrated funding possibilities. Channel Four, in particular, established in 1982 with a brief to 'encourage innovation and experiment in the form and content of programmes', was a boon to the industry. Through its production company Film on Four, later Film Four, Channel Four produced or funded 170 feature films in the 80's. Film production hit another of its all-time lows in 1989 as Channel Four decided to return to commercial TV and make programmes like Big Brother, but the introduction of public funding for films through the National Lottery began, just in the nick of time, to plug the gap.

Meanwhile, the problem of exhibition continued to come between audiences and documentaries. Little action had been taken to break up the Rank/Odeon and ABPC/ABC 'duopoly' so loathed by Clement Attlee and Harold Wilson, but, in 1985, the UK's first multiplex (AMC's The Point in Milton Keynes) opened. It ushered in a new wave of investment in cinema building which, half a century after the birth of the 'people's palaces' (the super-cinemas for the talkies era), challenged the duopoly. Sadly, despite promises to the contrary, documentaries and independent films, have struggled to find a home within the multiplexes. As Samantha Lay says in British Social Documentary Realism: From Documentary to Brit Grit: "It had been suggested that the advent of the multiplex would increase consumer choice; however, it has largely meant an increased choice of Hollywood product." A similar prognosis might be applied to the Thatcherite new dawn of competitive commercial television, which promised choice and delivered a hundred varieties of the same programmes.

Winston Churchill, although he regarded TV as 'a tuppenny Punch and Judy Show', was one of the instigators of the privatization of TV. Unsurprisingly, John Reith opposed him. In a famous speech in the House of Lords the doughty patrician said: "Somebody introduced Christianity into England and somebody introduced smallpox, bubonic plague and the Black Death. Somebody is minded now to introduce sponsored broadcasting." He was concerned that ethical and intellectual standards would decline with the breakup of the BBC's monopoly on TV. It is easy to guess what Reith would have thought of the 1990 Broadcasting Act, which took the Thatcherite project of competition, privatization and deregulation deep into the heart of our culture, exacerbating the trends toward 'dumbing down' and creeping Americanization. By stipulating that the BBC and Channel 3/ITV companies commission a quarter of their programmes from independent producers, the Act effectively reduced budgets for in-house productions. In 1992 Thames TV's This Week documentary slot ceased to broadcast. In 1998 Granda's World in Action slot followed suit.

Mercifully, BBC's Panorama survives as a reminder of the virtues of public broadcasting, in a television landscape that makes traditional Reithian paternalism look more attractive than it once did. In 2006, Panorama gave us Sex Crimes and the Vatican, in 2009 Whatever Happen to People Power?, in 2010, three days before the first papal visit to the UK in three decades, What the Pope Knew, and, last year, Undercover Care: The Abuse Exposed. The wave of independent production companies that rushed into the vacuum created by the Broadcasting Act, however, have tended to turn out cheaper, more profitable mock-factual and fictional programmes rather than more time-consuming and expensive drama and documentary. Docudrama, docusoap and reality TV increasingly rushed into the chasm separating the new dispensation's educational and public service obligations on the one hand, and the drive to maximize profits by providing bread and circuses for mass audiences on the other. Docudrama proliferated, but not as Peter Watkins envisaged it; docusoap too, but not as Paul Watson shaped it. Interesting new hybrid forms resulted from that clash of cultures and values, but the dramatization of fact became the prevalent mode of address. Audiences have become increasingly distrustful of the mock-factual programmes they watch, In his survey of docudrama, in Intellect's excellent Studies in Documentary Film series, Jonathan Bignell summarizes Annette Hill's survey of viewer reactions to factual programmes containing dramatic reconstruction. Over 70 per cent of Hill's sample viewers thought the stories were exaggerated or false, 45 per cent had difficulty discerning the difference between 'real' filmed stories and a recreations.

| David Rose and Important Stories |

|

That blurring of the divide between the real and the fictional might be a metaphor for contemporary culture. It means we not only need 'straight' documentary more than ever, but stories rooted in reality too. Respect for documentary and love of stories is not mutually exclusive. As the great American poet Muriel Rukeyser said: "The universe is made of stories, not atoms." Life-affirming, occasionally life-changing stories inform our understanding of ourselves, and of the world. Film delivers such stories by the thousands. I was reminded of some the best at the Sands Film Studios a few weeks ago. At the studios, in a converted granary on the banks of the Thames, I had the pleasure of an enlightening afternoon in the company of a man who may have given us more filmed stories than anyone else alive: pioneering producer David Rose, who makes no distinction between films for TV or Cinema. Awarded a Special Prize at Cannes for services to cinema in 1987 and recipient of a BFI Fellowship in 2012, Rose was the driving force behind one of British television's most fondly remembered series, Z-Cars, and one of its most glorious achievements, the BBC's Play for Today series. As if that were not enough, he also helped revitalize the British film industry in the 80s. While Channel Four's first Commissioning Editor for Fiction (and ably assisted by Peter Ansorge, Karin Bamborough, and Walter Donohue) he created the Film on Four strand, and guided 136 feature films onto our cinema and TV screens. When Channel Four celebrated its 25th Anniversary recently, David Rose wasn't invited to the party.

In his film, My Journey Together, Rose, a former RAF pilot, reminisces about his high-flying time in television. He tells an amusing anecdote from his time at the newly opened 13-acre BBC Television Centre in the early 60s. Due to its circular design and cosy corridors, the iconic building was often the scene of impromptu parties. The BBC's Head of Personnel at the time sent a directive out to all staff informing them that the building was not, repeat not, under any circumstances, to be used for the purposes of entertainment. While working at Television Centre and, later, at the Pebble Mill studios in Birmingham, Rose provided the nation with original, challenging entertainment of the highest order. At the BBC he nurtured directors like Alan Clarke, Mike Leigh, Ken Loach and John McGrath; and writers like Alan Bleasdale, David Hare, Peter Terson and Willy Russell. At Channel Four he did much the same for directors such as Terence Davis, Bill Douglas, Derek Jarman and Peter Greenway. We can thank David Rose, among other things, for such unforgettable classics as Boys from The Blackstuff, Comrades, Distant Voices/Still Lives, Nuts in May, The Last of England, Licking Hitler, Penda's Fen, A Very British Coup, and The Cook, The Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover. So, I'm not knocking stories, far from it, just grizzling at the overemphasis on stories at the expense of information and reacting against the mantra that insists it is on television, not in the cinema, that we are most likely to find innovative, edgy stories today. But that's another argument for another day. Rose trusted his audiences. He trusted his writers and directors too. They rewarded him with stories that challenged the national narrative and aided countless individuals in their search for more authentic selves at odds with social normality. The Pebble Mill Studios have since been demolished, BBC Television Centre is to be flogged off, the combative Channel Four of old has all but disappeared, and David Rose has retired. We may never see their like again.

* Film for Action's List of 100 Top Documentaries

|