|

When you've been watching films for as long as I have (which is a sly way of avoiding the admission that I'm a forgetful old fart), you do sometimes struggle to recall when you discovered the work of a particular filmmaker or even which of his or her movies you were exposed to first. So it was with Nicolas Roeg, a director whose films had a considerable impact not just on the young film student that I once was, but on pretty much all of my classmates. If I had to try and pinpoint when and where I first encountered Roeg's movies, I'm guessing it would be then and there.

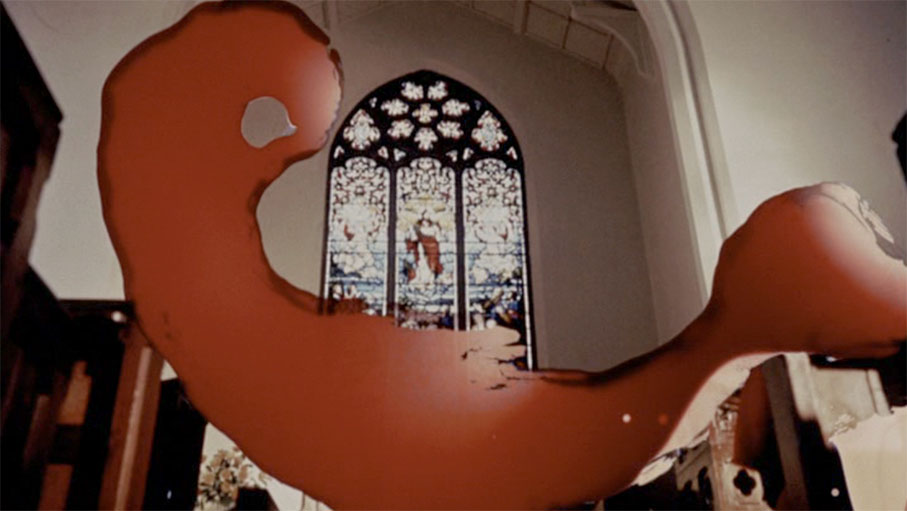

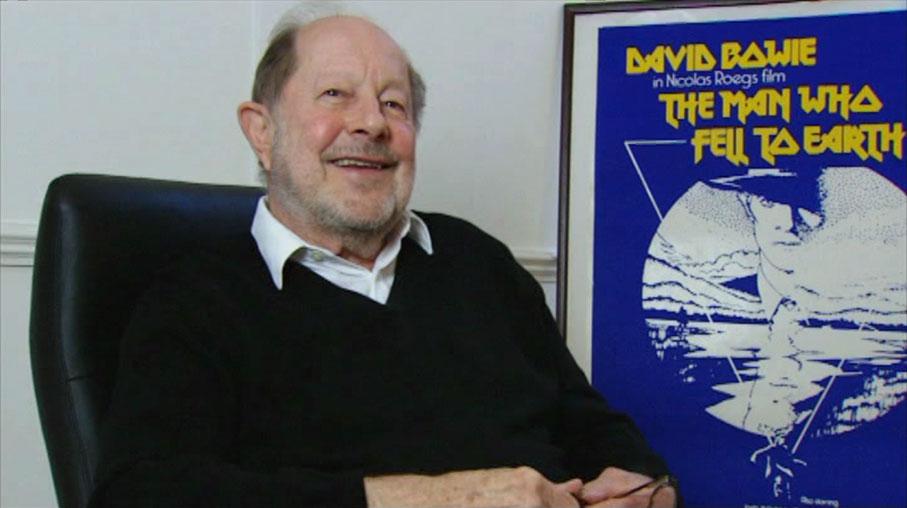

In the late 1970s, Bournemouth wasn't a bad place to study film and television. The college was within easy reach of a number of cinemas, including three with epic-sized screens and an arts centre with a small cinema that showed the sort of movies that you'd otherwise have to go to London to see. Every Saturday night the Gaumont – which had the biggest screen of all – would have a midnight screening, and despite the fact that many of those in attendance had just spilled out of the pubs and were thus pissed and a little rowdy, it seemed to us that the films they showed were not selected with this audience in mind. They were, we liked to think, picked specifically for us. I mean, look at this collection: The Day of the Jackal, The Mean Machine (aka The Longest Yard), Where Eagles Dare, Murder By Death, The Devil Rides Out, M*A*S*H, The Getaway, Inserts (this so needs a special edition UK Blu-ray release), The Birds, Rocky, Marathon Man, Suspiria, High Plains Drifter, Play Misty for Me, The Outlaw Josey Wales... I could go on. I first started attending these on the specific recommendation of one of my fellow students, who was excited as hell by what was programmed for that weekend. The film in question was Don't Look Now. A few months later it was The Man Who Fell to Earth. Can you imagine how the drunken hoard reacted to that when it spilled back out onto the street at 2am on Sunday morning?

As students still discovering the sheer breadth of what cinema had to offer, we became obsessed with these films, or at least the memories of them. Nowadays it's so easy to track down a favourite film and buy a high definition copy to watch whenever and wherever you choose, but back then almost the only way to see a film that was not currently on general release was to travel to London and scour the listings in Time Out in the hope that it was showing at one of the city's many independent cinemas. It usually wasn't. You could always hope for a TV screening, but back then there was no way that either Don't Look Now or The Man Who Fell to Earth would have made its way onto British TV without cuts and certainly not in the original aspect ratio. This is why these late night screenings were so important to us, and why we were prepared to tolerate the drunken wankers at the back of the cinema, many of whom would thankfully fall asleep long before the end. But here's the thing. While our other movie obsessions heavily influenced the films that we ourselves made, we were all too aware that Roeg's unique approach to scene structure, storytelling and editing was out of our league. Almost everyone there seemed to think they were Martin Scorsese, but no-one even tried to be Nicolas Roeg.

So unique and rule-breaking was Roeg's style, particularly his ability to shatter linear time without diluting the clarity of the story, that I still instantly reference him when discussing later films that dipped their toes in similar territory, as I did in my DVD review of Kitano Takeshi's Dolls. His distinctive approach also led to many wrongly assuming that the lion's share of the creative decisions made on Performance – his first stint in the director's chair – were primarily down to him, and it took later articles and documentaries to confirm that the film was a close collaboration between Roeg and co-director Donald Cammell and that if anyone it was Cammell who was the film's key creative driving force. Yet it was Roeg who was soon to establish himself as one of modern cinema's most visionary directors, first with the 1971 Walkabout and then, most emphatically, with Don't Look Now, which remains one of the most haunting, brilliant and influential thrillers of twentieth-century cinema. The rest, as they say, is cinema history.

It was only after I left film school that I became aware (in pre-internet days such information was harder to come by) that before becoming a director Roeg has been a cinematographer of considerable note and that he had also been behind the camera on Performance and Walkabout. His eye for colour and composition made Roger Corman's The Masque of the Red Death the most visually ravishing of the director's Edgar Allen Poe adaptations (and , I would argue, the best-looking film of Corman's long career). He also helped to bring a cool futuristic sheen to François Truffaut's 1966 adaptation of Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, as well as a richness to the landscapes in John Schlesinger's 1967 film of Thomas Hardy's Far From the Madding Crowd. In common with Alfred Hitchcock, he was too often passed over when it came to major awards (only three BAFTA nominations and no hint of an Oscar), but his impact on film culture and even popular culture is perhaps stronger than many realise. What follows may seem like a non-sequitur but go with me, it will make sense.

In my late teens, my love of punk and post-punk music was dominated by The Clash. I saw them live more frequently than any other group and bought every record they released. When they broke up it really felt like the end of an era, so I was fired up when lead guitarist Mick Jones teamed up with the group's regular videographer Don Letts to form Big Audio Dynamite. Sure, they weren't The Clash, but I really enjoyed their first album and still intermittently go back to it to lift my spirits. Their first two singles were taken from it, and the second – which is often cited as their most popular – was titled E=MC2 and delighted me by including samples from Roeg and Cammell's Performance. Only when I actually listened to the lyrics did I realise that the entire song was a tribute to the directorial career of Nicolas Roeg, something that becomes more obvious in the Letts-directed music video, which includes snippets from some of his key movies. Given that Roeg was never what you'd call a household name, I'd say such a tribute is kind of special. The plots of several of his films are alluded to (including a major spoiler for Don't Look Now), but I'll sign off with its concise late-song comment on Roeg's refusal to play by the rules and his subsequent importance and influence:

"It's assault course celluloid the money makers would avoid

Sometimes notions get reversed – centre of the universe."

Absolutely.

Nic Roeg was a cameraman and director, one of the very few who could be called visionary. Look him up. I don't need to list his credits. Nic Roeg was also the patron of the editors' guild (the Guild of British Film and Television Editors) of which I am a board member. No other director that I know of was more cognisant with the power of the cut.

But he was so, so much more than that.

Power. Cut.

Nic Roeg was the cultural avatar of the all-gendered cool kid who showed you that life was not what you thought it was. Nic Roeg was the spirit guide of all of us movie-obsessed freaks who thought that what they felt was aberrant and anti-society but was just – as in righteous – (aka creative), draped in another style of jacket. Nic Roeg was an infrequent but welcome Anti-Claus for all those kids who knew they were unapologetically naughty and therefore couldn't depend on the other guy to deliver. And what works that he delivered to those happy few that were artistically and deliriously astonishing.

Nic Roeg taught me more about human anatomy and sex than my nearest and dearest because he wasn't scared to do so. Talk about Walkabout. Nic Roeg had the perfect artist's name. Great artists steal (what better name than 'Nic'?) and like the shark very much unlike any other shark in Jaws… ("Now, this shark that swims along… What's it called?" "Rogue." "Rogue, yeah. Now this guy, he keeps swimming around in a place 'til the food supply is gone, right?") Roeg is a pirate's synonym – emphasis on the 'sin' – and Nic was a pirate who never ran out of food.

Nic Roeg may have run out of people and resources that could have maintained, supported, nurtured and expanded his artistic output but like the best artists he strove for and, more than most, thrust and pinned truth on his diverse and eclectic canvas. Storytelling as a commercial enterprise is never regarded as one of the arts. What did the guy have to do to prove that his level of artistry was just that? If you have to make good coin, never trust an artist. If you want minds blown and human creativity squeezed from contracting and fisted fingers then he was your man. Nic Roeg recognised (Christ, his name is almost an anagram of that verb, albeit ED-less and S-less) that the human being was not compartmentalised into tropes and canards and so his art didn't baseline those clichés. If Nic Roeg did anything at all, it was to acknowledge the complexity of the human experience, which is why an extra-terrestrial was sometimes needed to underline that point. And as we're swimming in sci-fi waters…

Nic Roeg once said that if you could travel forward in time to the finished locked and mixed cut of a movie, you could save 80 per cent of its budget. This was wisdom, wisdom that acknowledged that not only did you have to break the eggs to make the omelette but you had to make the time to chose to do so and take the time it took to choose and do so.

Nic Roeg's passing is comparable to the last curtain falling, one that protected us from the prosaic window of Trump and Brexit. Roeg's artistry, if it could be applied to today's political climate, is needed more than ever before. If he was in a heavenly green room with Bill Hicks then I hope the pair of them are champing at the bit to get back to Earth to right a few significant wrongs.

Cheers, Nic. We're not as accomplished or qualified to take the fight from here but we will do so with a fervency that may surprise even you.

Nic Roeg. The next world is simply not worthy.

1928 – 2018.

|