Author's Note: This review started originally with paragraph three in which I invoke the magical moment of 'Eureka!' as the discovery of the structure of DNA was made in a highly crafted BBC Horizon Special in 1987. I then covered many points about my interpretation of the movie Eureka and then to my delight and disappointment (I do cognitive dissonance in my sleep), writer Paul Mayersberg not only mentions everything I'd written up to that point in his interview on the disc (even Crick and Watson's DNA discovery) but in a far better and more lucid way than I did. This necessitated something of a rewrite. So to those nitpickers out there, I swear I did not play the Mayersberg interview and then write my review based on his comments. Thank you.

| |

"I wanted to make a film about ecstasy, the many forms of ecstasy, ecstasy in individual people, and ecstasy as the mystic sense of life. How our actions are connected to everything and everyone around us. It's not a mystery film, it's not a thriller. And I hope you can't put it into a slot. There isn't a slot to put it in. To do so would make it a thing it isn't." |

|

Director Nic Roeg* |

What comes to mind when I say 'adult film'? Yeah, right. Let's turn that around – films for adults. Director Nicolas Roeg makes fascinating, visceral, re-watchable and intellectually stimulating films for adults. It's shocking to me that this may need saying out loud but these days I can't say it loudly enough. His first seven movies, mostly the work he will be celebrated for, share a startling eclecticism made personally distinctive by his directorial and editorial style. He started his career as a noted cameraman working with directors like David Lean, John Schlesinger and François Truffaut but from my own editorially biased point of view, it's his cutting style that stands out a mile. You can usually guess you're watching a Nic Roeg movie by his glorious transitions and in-out flash cut juxtapositions – not that Roeg has any respect for linear time, and nor should he have. Roeg's editorial style is the only instance of the craft when I would ignore the usual cliché that good editing is invisible. Yes, his varied film editors, specifically Graeme Clifford and Tony Lawson must take some credit as it's very hard to believe Roeg had these transitions planned from the first shooting day. His filmmaking evolves and revels in expanding ideas made greater by happenstance over the course of the process. Filmmakers who storyboard can be as open to serendipity as the next man/woman (Indiana Jones shooting the Arab swordsman in Raiders comes immediately to mind) but Roeg seems fluid throughout the process and that lends his films a palpable air of excitement because you honestly cannot say where his films are going one scene from the next. In his own interview on this disc, film editor Tony Lawson suggests that Roeg left the first assembly to the editor. In his own contribution to this disc, Roeg states that he and the editor work very closely once the rough assembly is finished; now that I can well believe.

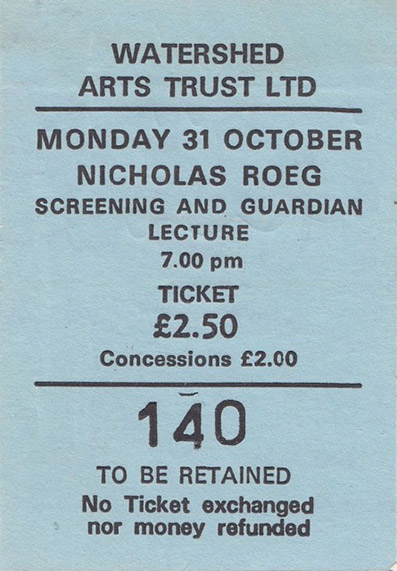

When I left the cinema after my first screening of Eureka, I was spellbound. The fact that it soon disappeared from cinemas was very disappointing. It would end up two years later being released in the US falling foul of studio upheavals. Here was a film for grown-ups with actors at the top of their game telling a fascinating story, a power struggle with damaged characters drowning in the currents of life-defining wealth. The screening I attended in Bristol featured Roeg in attendance (very similar to the Roeg Q & A featured as an Extra)**. He was doing the rounds promoting the film with a wired-up jaw after an accident. After the screening, as he sat down to address a very enthusiastic audience, he sighed and said that the film had been projected wrongly, cropped by the wrong lens. He caught the last five minutes so it was too late to correct the issue. It wasn't a great way to say 'Hullo,' but the evening was hugely memorable. Roeg is an unapologetic, iconoclastic filmmaker and we need (ironically) as many of those as we can get.

In Mick Jackson's superlative TV film Life Story, Jeff Goldblum as James Watson, the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, is standing on a bridge with his sister. It's just after the main event, Crick and Watson's big discovery. Goldblum says "When you want something, want it so bad it hurts and... then you get it..." Eureka is the story of a man whose life ended the moment he got everything he wanted. Prospecting alone in the snowy wastes of the Klondike in northwest Canada is a determined soul. Spiritually related to There Will Be Blood's ruthless oilman, Daniel Plainview, Jack McCann has eschewed any human partnership vowing over and over that "I never earned a nickel off another man's sweat..." and for fifteen years he has been seeking that elusive strike. In the nearest town's brothel, he shares a spiritual relationship with the madam, Frieda who sends him back out into the snow where McCann stumbles upon a gold strike of unprecedented size. Nothing, as the Rocky Horror song goes, will ever be the same... Just how McCann actually 'earns' the gold (the reward for looking for so long with so little to show for his labours?) is in question and this precise idea is stated at a dinner table much to the rich man's chagrin.

Many years later McCann, now deliriously rich, lives a cavernously hollow life on his own Caribbean island with his frequently inebriated wife. You can tell he's wealthy because he wears a muumuu. McCann's beloved daughter is in love with playboy Claude and let's just say that McCann is not a fan. Being taunted by Claude from one side (the affections of and relationship with his daughter both at risk), he is also being approached by mafia entrepreneurs and their associates who are looking for permission to build a casino on McCann's land. Jack, staunchly unlikeable all throughout the movie, sticks to his guns, refuses to emotionally release his daughter and unmindful of what may happen, he turns down the many offers from the entrepreneurs. After a climax of unflinching barbarity, a terrible crime is committed and the courtroom drama third act pits loved ones against each other in a battle for their souls. And that's a simplified version of events.

Roeg doesn't do the Hollywood three act model even though Eureka is divided neatly into three distinct chunks – prospector strikes gold (25 mins), unsympathetic rich man assailed from all sides (1 hour, 12 mins) and the courtroom drama resolution (32 mins). And one common complaint about the movie is that the third act scuppers the other two in terms of drama and visual interest. I found the courtroom scene compelling, superbly acted and drawing a morbid and touching veil over the whole proceedings. Other filmmakers may have climaxed the movie with the barbaric act and put title cards up explaining what actually happened at the court case but although this story is based on real events, Roeg and writer Mayersberg threw out all the real names and changed them to give them the freedom (as Picasso said) to lie to get at the truth. You cannot bind a man with Roeg's sensitivities and proclivities to the lumpen weight of the actuality. Freedom to soar is also accompanied by the very real possibility of plummeting. The risk of failure is success's rocket fuel. Everything depends on which direction you're looking and Roeg is always, in one way literally, shooting at the stars. He's a filmmaker who's also aware that film time can be slashed, broken up and generally disregarded altogether in search of a relevant and dazzling idea or metaphor. In short, and playing somewhat in the mainstream, Roeg is an experimental artist up to the point that he can raise money by convincing the studios that he's nothing of the sort.

There are Roeg's common thematic concerns woven throughout the narrative (such as time, destiny and the supernatural) as well as well-distributed visual tropes. There are many reflective surfaces and lead characters often come in contact with mirrors at emotional moments and events are foreshadowed and intercut with creative abandon. Some of the cutting, as in all Roeg's films, makes me squeal with delight. Some transitions are audacious in terms of ideas but the stand out scene of Eureka is a masterpiece of suggestive, associative editing. When McCann falls into an ice cavern where he will find his great discovery, the action is intercut with icy mountain scenery increasing in movement from static to zoom to wild 360 degree pans. Just before he starts to use his pick-axe, McCann touches the wall of rock as if he would a lover's hip or shoulder. Frieda coughs in reaction (the subtlety of this kind of cut engenders such respect from me and you never know if its discovery is luck or judgement. If it's the former, then recognising it deserves kudos). The climax ably accompanied by Wagner's opening to Das Rheingold on the soundtrack (the hoard of gold guarded by the Rhine maidens, naturally) is suitably orgasmic but the editing doesn't let you go. We are in the surreal realms of signs and their meanings here and of course metaphorically, despite covered in the stuff for which he's been looking for years, this is the first moment of McCann's slow death. He will never feel this way again and will always be gnawed to pieces by this moment of ecstasy's memory. He also develops an exquisitely paranoid nature regarding everyone's behaviour towards him – or what he represents. Once he's back with a dying Frieda – his dripping, thawing face provides her tears, a masterstroke of direction – a coal is spat from the flames and in a cut that rivals a certain bone/spaceship juxtaposition in terms of time having passed, we are twenty years down the line, a greying McCann brushing a lit coal off his coat. A sofa design behind the shocked and grieving Claude (at about 58 mins, 18 seconds in) directly echoes the blood soaked pillows to be found at the scene of the barbaric act. If we want to bring sex into the mix (as Roeg invariably does), Frieda says that Jack's cock and her crack was "a crock of gold, more than love. It was a power..." This metaphor sends Jack into the cold wastes where his phallic pickaxe penetrates a crack in the wall and out comes... Perhaps better not belabour that one. But there are so many readings provoked and tickled by Roeg's cutting style that to write about them you're almost falling over yourself with the cascade of creative thought that's gone into the work. This is how dense movies should be. It is clear I mean packed with ideas and not idiotic, right?

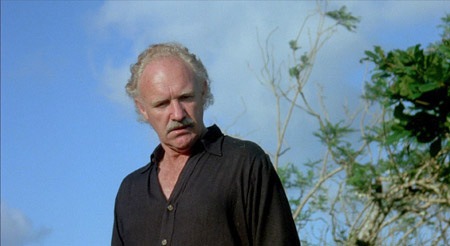

And I haven't even mentioned the actors. No leading man of his generation was ever so willing to be so unlikeable, all the time. Jack McCann is a paranoid powerhouse with a physical intimidation and a justifiably cynical take on humanity. No other actor but Gene Hackman could have pulled Jack off (sorry, just the way the words came... sorry again) so superbly convincingly. He's not a nice man but he is compelling. He's also got a look that allowed him to play men of vaguely indeterminate age (he was 41 in The French Connection and so 53 in Eureka) and also easily convinces playing a man ten years older and younger than he actually was. He really grounds the film as the character that everyone is reacting against or rather what he represents. He also gives the idea of wealth bringing happiness into serious doubt and that is just as it should be. Helena Kallianiotes plays past love Freida with exactly the right amount of far away mysticism. The half-cut wife with whom McCann once shared a romantic honeymoon period, is played by Jane Lapotaire, a British TV regular and once wife of director Roland Joffé. Ex-model, Theresa Russell, far too famous for being Nic Roeg's wife at the time rather than the alluring and effective actress she is, plays Tracy McCann, the source of father Jack's (R.I.P. Ted fans) only pleasure. The fact she married a man whom her father despises seems to make her stronger. Her beau, the impossibly chiselled and striking Rutger Hauer, a year after his stunning turn in Blade Runner, plays Claude van Horn. He is scornful of wealth despite having it himself and despite his wanderings with voodoo debauchery, his love for Tracy seems sincere until a confrontation reveals something that lovers and loved ones should never reveal about themselves – their own truth. Relationships are spun on webs not strong enough to survive after the blowtorch of personal truth. I would say more about the blowtorch but will leave that for you to discover. On the villainous side of the cast sits the entrepreneurial crime boss Mayakofsky played with an enormous cigar by Joe Pesci. At last, Pesci gets to play a boss and not the sidekick. His lawyer and the man who witnesses the slow destruction of Jack McCann and sees an opportunity with Tracy once her husband is out of the way, is the post Diner youthful and angelic face of Mickey Rourke playing D'Amato with a voice like a sugared whisper.

The screenplay by Paul Mayersberg is no ordinary piece of work. In the first twenty minutes all the characters seem to talk in pithy aphorisms and most of the dialogue is mannered and oddly formal, a lot of it jackdawed from a great many literary sources. Mayersberg admits to his sources in his interview, which is honest and oddly refreshing. But he admits it almost with a mischievous twinkle in his eye. It's a maxim in the writing community that 'Good writers borrow but great writers steal.' This has always been the case. But this is what Roeg wanted. Naturalism in dialogue doesn't give you the opportunities for layered ideas as much as crafted maxims... Try these for almost totemic pronouncements; "Gold smells stronger than a woman..." It doesn't but you get the point. "Everybody pays." Yes, they do. "It's not over until it's over," with no fat lady in sight. "There's some left-over life to kill," so, he's a dead man walking. "I've reached the edge of eternity, beyond eternity..." Years before Buzz. "Do unto others as they do unto you, everything else is conversation." Nicked wholesale from Rabbi Hillel's famous reply to a gentile wanting to convert to Judaism. "Once I had it all, now I just have everything." A soul brother to "The future's ain't what it used to be..." from baseball legend, the rather quaintly named Yogi Berra.

Yes, there's an argument in stating that the film's style has dated. There are plentiful zooms which tend to nail down a film's production date range but unlike Michael Winner whose use of same was crass and over the top, Roeg's zooms are sly moves towards characters inviting us to adjust, to edit as the shot progresses. They never feel like they've stepped in from another century. I could write another few pages on the use of mirrors in this extraordinary movie but will leave it there. Like Hauer's vicious slap meted out to his wife and then an instant later a bear hug of need and remorse after hearing about the death of his mother, Eureka slaps you in the face with its unsympathetic lead character. Then, with ideas and metaphors as the comparison to the resulting bear hug, it dares you to embrace its ideas and craft and a cinematic intelligence that is unique and at times dazzling.

The 1.85:1 restoration from a 4K transfer in 1080p HD on the Blu-ray is solid with stable blacks and an overall pleasing contrast. I'm thrilled to see the two very thin black lines at the top and bottom of screen... So many 1.85:1 framings have been 'modified' because we've all got to have our plasma's full up, haven't we? No. 'Modified to fit your screen?' My ass. Well done Eureka and Eureka. The grain is most visible (as to be expected) on the, one assumes, 'multi-generations from the original' MGM Logo but the feature is mainly free of such distractions and damage. It's scrubbed up very well. The colour timing (the word for grading in the 80s) displays some odd moments of bizarre hues but I think this is what happens when you mix from gold to blue hued snow white, particularly in the prospecting climax. You have to visit an unhealthy shade of green along the way, a real world chemical dye issue. But generally, this is a cracking transfer visually speaking.

The PCM Mono is clear throughout despite the film's relative age. There is never any difficulty in understanding the dialogue and the creativity in the rest of the soundtrack, while being best served by a surround sound mix, sadly probably non-existent, is still notable in its original mono iteration. There are optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing-impaired.

Audio recording of Q&A with Nicolas Roeg at the world premiere – contained as a separate stereo track on the movie, placed instead of a scene specific commentary (1 hour, 39' 30")

Ah, the time when this film was just coming out, the world was its oyster. What the hell went wrong? Eureka was two years in limbo before it crossed the Pond due to studio regime change and the ousting of studio head/known embezzler, David Begelman. This was an NFT screening (National Film Theatre for those of you unfamiliar with the initials) on the 12th February 1983 with Roeg interviewed on stage after the movie by then Guardian critic Philip Strick. There is a sustained applause as Roeg is introduced that stirs me and makes me smile. If you are going to find Nic Roeg fans, then a World premiere in London sans red carpet is the place to be. I now realise that my cinematic viewing must have been while Roeg was on this series of publicity jaunts because we were also told that his broken jaw was wired in Bristol.

Roeg is not an effusive speaker and does most of his talking with his images but if you add to that a wired up jaw, there is some effort to make him out a lot of the time. Amps up to eleven if you want to hear the audience's questions at the close but most come through. Here are some of Roeg's thoughts, the ones I responded to... On Lawrence of Arabia, under the 2nd Unit direction of Andre de Toth, Roeg explained David Lean's reaction to one of de Toth's more outrageous ideas... Working with Roger Corman taught Roeg to work fast. Working with Truffaut (as cinematographer on Fahrenheit 451) was 'special'. Incidentally, the camera operator on 451 was Alex Thomson, Eureka's own cinematographer. On Performance, "...there wasn't a script!" Artists often have the same obsessions and move their thoughts of them to another step. He also said that audiences were not challenged, or not even thought of at all... That was true then and now. As an audience, we're just demographics. Finally, Roeg admitted that he doesn't pre-plan at all as this may "...take away what may happen..." Well said. My own motto on shooting is 'Be prepared and be prepared to throw away the preparation.'

Exclusive new interviews with:

Producer Jeremy Thomas (13' 35")

Legendary producer Jeremy Thomas gives us the origin story of the film and describes the various locations used and the dangers posed by the arctic conditions. He talks about studio regime change, preview screenings, and the changes demanded by the new studio. Fascinating for those of us desperate for background detail from a trusted source.

Writer Paul Mayersberg (53' 18")

Almost an hour of Paul Mayersberg holding court on the genesis of the film, the historical reality and the creative process working with Roeg and every minute is a certified gem (if I was giving out the certificates). Cunningly edited, it seems as if Mayersberg just starts with Harry Oakes (the real life McCann) and ends on the unattainable quest talking straight for almost an hour. The descriptions of how the script took shape, twenty pages at a time, makes me yearn to collaborate with fellow filmmakers in a similar fashion.

Editor Tony Lawson (13' 06")

Another self-effacing editor slightly under-cutting (!) their own contribution to the final work, this interview with Tony Lawson is brief but illuminating all the same. Lawson has worked with Kubrick and Peckinpah and suggests that editing "is just editing," whoever the director. There's some truth in that statement – you are serving the story at all times but his working relationship with Nic Roeg seems to be much more collaborative. Roeg shoots material that he freely hands to the editor without notes rubber-stamping a creative partnership that we editors have known about for a long time while the director gets most of and in most cases, all of the credit. To be fair, in Roeg's case, it's only the first assembly that the editor is directly responsible for. From then on, it's a total collaboration.

Isolated music and effects track

Again, my confusion at the inclusion of the M&E... It's lovely that it's available but it's a functional soundtrack that enables non-English dubbing. Who is ever going to play it? Music soundtrack aficionados perhaps (composer Stanley Myers haunting work is not available on CD or vinyl) but then there are sound effects over everything.

Theatrical trailer (2' 42")

This is a surprisingly good, beautifully edited trailer with more than a few existential nuggets to unpack. There's liberal use of the most famous piece of music in the movie (The Rheingold) and if I had actually seen this, it would have intrigued me enough to commit to it as a potential audience member. And that cast!

A booklet featuring an excerpt from Roeg's autobiography, a new essay by Daniel Bird, a reprinted interview with Roeg and Robert W. Service's poem The Spell of the Yukon

This is another winner from Masters of Cinema, even just the loving attention to the re-design, a terrific updating of some of the core imagery. It is very inviting. Roeg's own autobiography extract is short but telling. First there's the mention of the use of mirrors available in the great colonial house and secondly the belief that the movie was mistimed, being released in the era where it was said that 'greed is good'. Yes, the 80s. I don't miss them. Daniel Bird's essay is revealing, parking on many points the film raises and dissecting them with some relish. Again, I swear I didn't read this article and then quietly steal from it. In fact I am reading it for the first time now and cursing myself for missing some of the points he raises. The 1983 Monthly Film Bulletin interview with Nic Roeg is extremely interesting. He mentions shot but unseen scenes that clarified the link with the cosmos, regretted the lack of war signifiers in the movie and celebrated the utter 'rightness' of the title. Roeg also gives away what he uses as a talisman. The poem is the poem (not my area but it serves the movie well). There are notes on viewing and Blu-ray and DVD credits. All in all, this is a terrific physical extra.

Eureka is a bold, experimental drama about how ecstasy can destroy a man directed by an artist at the height of his creative enquiry. It's not for everyone (nor should it be) but if you connect and are sympathetic to its ideas and conclusions, it's a film that will stay with you for a long time. From this reviewer, Eureka comes highly recommended.

* http://americancinemapapers.homestead.com/files/EUREKA.htm

I sincerely suggest that you read the whole piece. It's one of the rare examples of Roeg peeling back a few layers and there's gold to be mined in that situation.

** Thanks to fellow attendee Paul New for confirming the date of this screening – 31st October 1983. If the NFT premiere date is correct (12th February), the Bristol Watershed screening was eight and a half months later so Roeg’s wired jaw must have been unwired and significantly better but I distinctly remember asking the great man himself how his jaw was… Not a question that exactly furthers cinematic appreciation but it seemed the right way to introduce myself. Do jaws take that long to heal? Or was the NFT date mistaken?

|