60 Years of Superlative Performances –

Gene Hackman, RIP |

|

| With the news that Gene Hackman has passed away in as-yet uncertain circumstances at the grand age of 95 along with his wife Betsy Arakawa, Camus pays trubute of one of the very finest and most beloved screen actors of his generation. |

|

| |

|

There is a very rare kind of actor who upends and subverts the traditional and clichéd boxes that actors are often placed inside. As a screen presence, you are either a ‘character actor’ (is there any other kind?) or a ‘star’. Once you are a star, people will pay more to see you and not the role you are playing. Only the very few get to flit between both ‘character’ and ‘stardom’ boxes. Two come to mind. There’s the ultra-committed Daniel Day Lewis, now retired and the unfailingly professional and always great Gene Hackman, recently deceased. I won’t linger on the odd circumstances of his passing (he was found with his wife and one of his three dogs also deceased…) and instead let’s take a dip into an extraordinary career.

Friends with a certain Dustin Hoffman while in a California acting class, both men were voted ‘Least likely to succeed’. With a will of iron, Hackman made it his life’s work to prove his naysayers wrong. You might say he over-compensated. His 60 year career was punctuated with a few Oscars, BAFTAs and Golden Globes and to my mind, he never turned in a dishonest performance.

Starting out, he mixed theatre work with a smattering of small parts in films and first came to wider recognition playing Buck Barrow, Clyde’s doomed brother in Bonnie and Clyde (1967). At 37, Hackman went back to act in TV until he was cast in the role that, despite his 95 films and TV shows, would define the Hackman persona, one he staunchly resisted going on to diversify his roles throughout his long career. Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle was a role of a lifetime. Director William Friedkin initiated the 70s rogue cop genre with The French Connection. Hackman played the cop with an almost preternaturally amped up frustration with violence only just below the surface. The film was also notable for the good guys not getting the bad guys in the end. Or specifically, ‘the’ bad guy. Aside from a few guest starring roles on the comedy show Rowan and Martin’s Laugh In, Hackman’s career was kickstarted by a Best Actor Oscar for The French Connection and movie stardom beckoned and was promptly swatted away by Hackman’s ambition to be an actor, not a star, taking on a huge diversity of roles.

From my perspective (and there are a great deal to choose from), here are my most treasured Hackman moments in chronological order;

- The preacher sacrificing himself in The Poseidon Adventure (1972) cursing God as he shuts off the steam valve, always a winner. He drops into a flame topped body of water, a drop that would have barely affected an 80s action hero. That always bugged me and I always half-expected him to turn up at the close, joining his fellow survivors at the propellors of the upturned ship, smiling beatifically saying “I knew we’d make it in the end,” no pun intended.

- As Harry Caul, expert sound-bugging man reduced to a mass of paranoia, he sits alone in his torn up apartment at the end of The Conversation (1974) playing his mournful saxophone.

- There’s his oft-quoted ‘uncredited’ cameo as the blind man making life difficult for the creature in Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein (1974). He was credited just not with the sizeable credit a star of his then magnitude could have insisted upon. He just wanted to play comedy.

- In another remarkable performance showing an immense range and command of his craft, Hackman revisits his most famous role but this time as a heroin addicted Popeye Doyle attempting to go cold turkey in The French Connection II (1975). I remember being stunned watching how convincing he was suffering from withdrawal symptoms.

- Hackman gets to deliver the greatest line in superhero cinema in Superman (1979). As lines go, it’s right up there even without the ‘superhero’ caveat. While Superman is compromised underwater wearing a necklace of kryptonite, Lex Luthor has revealed his plan – having bought up all the wasteland east of the coast of California – to detonate an explosion causing an earthquake centred on the San Andreas Fault thereby becoming the owner of the new Californian coast. He says, “We all have our faults… Mine’s in California.” Priceless.

- Then there’s Jack McCann, a gold tycoon driven to distrust all around him in Nic Roeg’s criminally underrated, largely unseen and unbelievably good, Eureka. It’s a bravura performance that the entire film grows organically from.

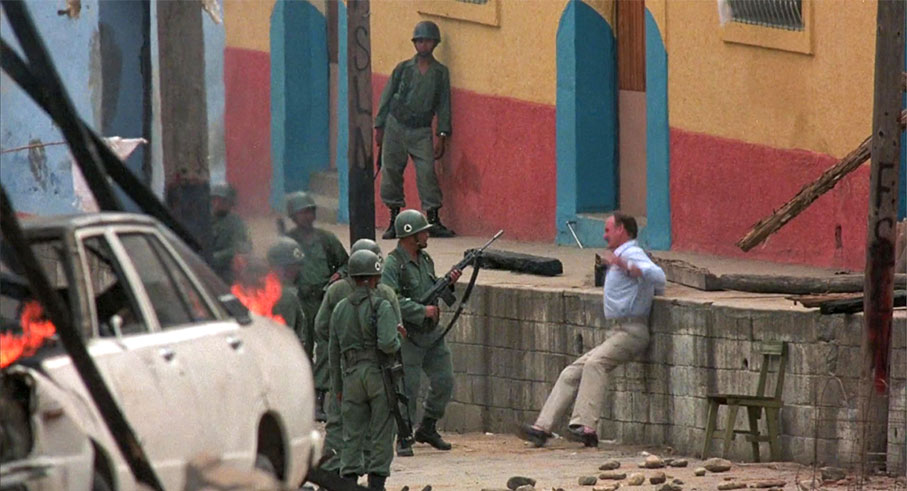

- Apparently, actors enjoy dying on screen. Who knew? In Under Fire, Hackman walks off to a militia roadblock to ask for directions in war torn Nicaragua. As Nick Nolte watches, we see only what he can see from a distance. Shockingly, one of the troops walks up to Hackman and shoots him in the chest. He falls against a wall as realistically as any actor has ‘died’ on screen. The way he sells this moment is as shocking as the moment itself.

- In Mississippi Burning, Hackman’s character is to Willem Dafoe’s as Connery’s is to Costner’s in The Untouchables. He’s the guy who knows what works while his younger superiors are walking the wavy line of trying to stay morally upright. His intimidation of Michael Rooker (you have to be especially intimidating to frighten Rooker) is a classic Hackman scene. To be fair, Rooker does his part by being utterly convincing having his testicles squeezed to bursting. “Thanks for the beer!”

- Finally, it’s hard to ignore his other Oscar winning turn in Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. As he disarms and kicks “English” Bob multiple times as an example to other bounty hunters not to look for ‘whores’ gold’, Hackman moves in for one last rib-cracking strike and almost as an afterthought, slips off his Stetson and swipes Bob with it ineffectually. As he wipes his head, his frustration morphs into a subtle incredulity that people could be so dumb to muscle in on his patch. He picks up his hat, brushes it off and looks at it as if it still carries the stain of the man he last swiped. Later, in a jailhouse speech, Hackman’s “Little” Bill Daggett takes the western by the scruff of the neck and demythologises it with a story of ineptitude, bad luck and cowardice. Fairness and justice in the West of Unforgiven are absent parties. And there aren’t that many actors who could face up to Clint Eastwood and get to call him “…a cowardly son of a bitch.”

I sincerely hope the circumstances of his death, when they eventually come to light, don’t overshadow what the man achieved in an extraordinary career. The only significant upside of a great actor’s death is the wealth of work that’s left behind. And it’s such a legacy that all but guarantees a slice of immortality. RIP, Gene Hackman.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Below is a small selection of the films in which Hackman appeared during the course of his 60+ year career as a screen actor. They have been by Slarek, who heartily recommends each one for Hackman's performance in them, and in the vast majority of cases for the films themselves. Just take a look at some of the directors that this remarkable actor worked with over the years. |

| Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) |

| Downhill Racer (Michael Ritchie, 1969) |

| Marooned (John Sturges, 1969) |

| The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971) |

| Cisco Pike (Bill Norton, 1971) |

| Prime Cut (Michael Ritchie, 1972) |

| The Poseidon Adventure (Ronald Neame, 1972) |

| Scarecrow (Jerry Schatzberg, 1973) |

| The Conversation (Francis Ford Copolla, 1974) |

| Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks, 1974) |

| Night Moves (Arthur Penn, 1975) |

| French Connection II (John Frankenheimer, 1975) |

| A Bridge Too Far (Richard Attenboirough, 1977) |

| March or Die (Dick Richards, 1977) |

| Superman (Richard Donner, 1978) |

| Superman II (Richard Donner, Richard lester, 1980) |

| Reds (Warren Beatty, 1981) |

| Eureka (Nicolas Roer, 1983) |

| Under Fire (Eoger Spottiswoode) |

| Hoosiers (David Anspaugh, 1986) |

| No Way Out (Roger Donaldson, 1987) |

| Mississippi Burning (Alan Parker, 1988) |

| Unforgiven (Clint Eastwood, 1992) |

| The Firm (Sidney Pollack, 1993) |

| Geronimo: An American Legend (Walter Hill, 1993) |

| Wyatt Earp (Lawrence Kasdan, 1994) |

| The Quick and the Dead (Sam Raimi, 1995) |

| Criimson Tide (Tony Scott, 1995) |

| Get Shorty (Barry Sennenfeld, 1995) |

| The Birdcage (Mike Nicols, 1996) |

| Absolute Power (Clint Eastwood, 1997) |

| Enemy of the State (Tony Scott, 1998) |

| The Royal Tennenbaums (Wes Anderson, 2001) |

|

|

| article posted |

| 1 March 2025 |

|

|

| See all of Camus' revciews and articles |

|

|