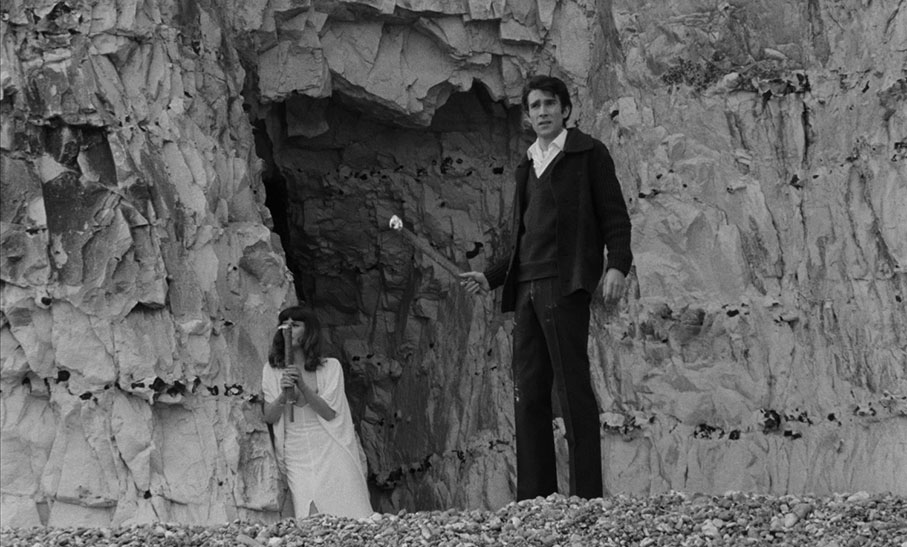

Note: due to the copy protection on this UHD disc I have been so far unable to get screen grabs from it, so have included screen grabs instead from the Blu-ray edition instead. My sincere thanks to Gary Couzens for providing me with these.

| |

“When we finished the mixing, we were all quite discouraged because we didn’t understand the film we had made. We didn’t get it. We didn’t know what it was about.” |

| |

Jean-Denis Bonan, editor of Rape of the Vampire |

As potentially problematic titles go, The Rape of the Vampire (an accurate translation of the French original, Le viol du vampire), the debut feature from French genre director Jean Rollin, is something of a peach. Quite aside from its teasingly ambiguous nature – is the vampire in question the rapist or the victim of rape, or perhaps even both? – the use of the word ‘rape’ in the title of a fantasy horror film would absolutely be frowned upon today, and with good reason. We have, I would hope, come a long way since the “I like rape” gag in Blazing Saddles and the “Been out raping, lad?” exchange in Yellowbeard, and the sensitivity with which the subject is now rightly treated could potentially create its own problems for a film that is much more than this sensationalist sounding title might suggest. Indeed, author and film expert Tim Lucas opens his commentary by revealing that when he started a discussion on Facebook about the film, contributors would replace letters in the offending word with asterisks to avoid triggering the platform’s censorial algorithm. It’ll be interesting to see what happens when I post links to this review on social media and put the title in capital letters.

The title alone has the potential to offend and upset some, particularly those who have been victims of this heinous crime, and if you’re worried about the possible content of such a work, know that on its French release, audiences were so outraged by it that they were shouting at the screen. What was it that so upset so many people? Too much sex and violence, perhaps, or a particularly egregious treatment of women in order to make good on that title? Well, not quite. If you fancy trying to guess the true reason before I reveal it, take a hint from the quote at the top of this review. I took that from an interview on this disc with the film’s editor, as he reflects on how he reacted to the film after he had completed the edit and the final sound mix. Despite being given a near free hand by Rollin to edit the footage how he pleased, even completing this task he didn’t understand what he been so instrumental in creating. Now imagine an audience that has paid good money to see what they think will be a Hammer-like vampire movie, only to be presented with a work that it could barely comprehend. Making matters worse was that the film was released slap-bang in the middle of the Paris uprising of May 1968, a time when revolution was in the air and many of those flocking into cinemas screening the film were doing so primarily to escape from the police, only to be presented with a film that they mistakenly believed was mocking them. Anger was in the air, and much of it ended up directed at Rollin’s movie.

I should probably admit here that only became aware of much of the above after making my way through the special features on Indicator’s new UHD. Often when reviewing a disc I will write the bulk of my review of the film before moving on to the special features to avoid being influenced by the opinions of others, even if this sometimes backfires when the contributors say the same things in a similar way, instantly making my efforts look lazily plagiarised. Here, however, I needed those special features like never before, because try as I might, there were times when I was as bemused by what was unfolding as those who were confronted by it back in 1968. At others, however, I was captivated, though not always for reasons I could easily explain, and after wading through the mountain of special features on this disc, I watched the film a second time and so much that mystified me on that first viewing became clear. That doesn’t mean it tells a cohesive and clearly defined story or that everything makes sense, because it absolutely does not, the result in part of Rollin’s improvisational approach, and a script that was being written and rewritten during the course of making the film. Compounding things further, almost everyone involved in the production was new to feature filmmaking, and the actors were all either friends and associates of Rollin (who even has a small role himself) or people he met and persuaded to play a part. Apprehensive yet? Well wait, as there’s more. Having initially completed what was originally a 45-minute film, Rollin was then offered the opportunity by his American producer Sam Selsky to expand it to feature length by extending the story further, a task seriously complicated by the manner in which the first part concludes. Rollin thus brought in new characters, found ways to bring characters that had died back to life, and took the story in a whole new direction. Challenging cinema? Oh yes, but if you’re patient and receptive to experimentation and the lessons learned from the French Nouvelle Vague and the avant-garde, it also proves oddly rewarding and artistically exciting cinema, and I say that knowing and fully accepting that some will think that such a claim is evidence that I’ve lost my marbles.

So, after three lengthy paragraphs of introduction, what is The Rape of the Vampire about? In Part One, four young women live an isolated existence in a castle and are convinced that they are vampires, one of them believing she was rendered blind after seeing her sister raped years before by men from the nearby village, hence the title. Commanding them and effectively keeping them prisoner in the castle and its grounds is what looks like a statue ot Jesus that has been transformed into a grotesque gargoyle of a Vampire God, while wooden crucifixes made by the local villagers effectively block all exit routes. Arriving from Paris to ‘cure’ them of what they are convinced is a group delusion are psychoanalyst Thomas (Bernard Letrou) and his friends Marc (Marco Pauly) and Brigitte (Catherine Deville),* none of whom believes in the existence of vampires. Thomas discovers that two of the girls do indeed have a vampiric aversion to sunlight, but when he bursts in carrying a large wooden cross and forces one of them (Solange Pradel) to grasp it, it has no negative effects on her, and she starts to realise that her condition may be an illusion after all.

Already we have proposals that feel new to vampire cinema of the time and that mark the start of a revisionist turning point for the genre. George Romero’s masterful Martin, in which a young man convinced he is a vampire may be no more than a seriously mixed-up kid, was still almost a decade away at this point, but the seeds for that film are being sown here. Having questioned the very concept of the supernatural vampire, the film then reveals that the Vampire God that controls them is also a sham, with the orders it dishes out are shown to be delivered by the local Lord of the Manor (Doc Moyle) from behind the edifice for his own only vaguely hinted at reasons. This dude proves a destructive force all round, ordering one of the women to kill the newcomers after the burn all of the crucifixes surrounding the castle, then riling up a group of local villagers by claiming that these visitors are in the process of setting the vampire women free.

And so we once again reach that point in the review where I feel it only right to give newcomers the chance to sidestep possible spoilers. Discussing the second part of the film in even imprecise detail will inevitably involve revealing some key details about the first, so if you have not yet seen the film and want to go in as coldly as possible, I’d skip the next two paragraphs or click here to do so automatically.

Right, for those who are still with me, there’s an interesting twist at the tail end of the finale of the first part of the film. Having proved to the one girl (I do wish Rollin had given them names, but it’s his movie not mine) that she cannot be harmed by a crucifix, and even found a way to restore the sight of the blind girl (Nicole Romain) – which immediately and ironically backfires – Thomas invites the girl he first helped to give him a ‘vampire kiss’, and when she does so he learns the hard way that after all his work, the girls really are vampires after all, and now he is one too. Prior to this, in the tradition of Frankenstein movies of old, the villagers rush to the castle to wreak havoc on its occupants in an assault that leaves key characters dead by the time first part reaches its end. And if you approach the film unaware of its two-part structure, the arrival of Part Two just 32 minutes after the film begins is likely to give you a bit of a jolt. Rollin makes no attempt to invisibly transition to the new material here, instead loudly announcing its arrival with the title Part Deux: Les Femmes Vampires (The Vampire Women), complete with its own set of opening credits. That said, this new story does dovetail seamlessly into the first, as the Lord or the Manor is surrounded and overpowered by a group of robed vampire women on the beach to which Thomas and the blind girl have fled. As he lies tied up and helpless, the Queen of the Vampires (Jacqueline Sieger) is carried out of the sea on a sedan chair, and calmly executes him with a curved dagger that she then licks the blood from in what has become the film’s most iconic image.

Blessed with a slightly higher budget than was scraped together by Selsky for Part One, the second half is longer, has a wider range of characters and locations, and is even more adventurous in its genre revisionism. First up, it proposes that vampirism is not a supernatural curse but a medical condition, one that could theoretically be isolated and cured with a biological antidote, which is developed here by Thomas with the help of a Dr. Samsky (a composite of the producer’s first and second names, played by an uncredited Jean-Loup Philippe), who, like Thomas, is effectively being held prisoner by the Vampire Queen in a hospital in which new victims are prepared for her to feed on. Also worth a mention are the girls who stand naked and trance-like whilst acting as living blood-banks, their blood draining slowly into large bell jars from which the Queen and her minions can feed. Now I should point out that neither of these intriguing ideas are actually new. The notion of vampirism as a curable biological condition was explored back 1945 in the Universal crossover genre film, House of Dracula, and the idea of women being used as living blood banks dates back several centuries, being one of the stories that emerged following the arrest of Countess Elizabeth Báthory in 1612. But with Hammer having since re-established vampires as the supernatural blood-sucking creatures of old and Countess Dracula still three years away, these notions still signal a potentially fresh new direction for the genre.

So far, so intriguing, so what’s the problem? Well, I’d be lying my face off if I claimed to have drawn all of the above from my first exposure to the film, as it took some useful nudges from the special features and a second viewing to clarify things. Rollin stages sequences stand-alone scenes that do not always connect directly with the action that precedes or follows them, and spoken exposition is rarely employed to fill in the gaps that result. Some scenes also require a bit of lateral thinking to decipher, including the opening duel set in the distant past that I only later twigged was a component of one of the vampire women’s origin story. Even then, was I looking at history or the invented creation of a woman who believes she is a centuries-old vampire? Your guess here would be as good as mine. This approach can sometimes prove jarring, and back when it screened in Parisian cinemas, the audience couldn’t put the film on pause and wind it back to take another look at what they’d just seen (I didn’t do this, by the way, but did revisit individual sequences later). Adding to the trippy nature of Part Two is a switch from the classical music of the previous scenes to a sometimes borderline avant-garde score by French free jazz pioneer François Tusques, music that reflects and enhances the film’s improvisational approach and disorientating structure to help create what may be cinema’s only authentically free jazz vampire movie. As is claimed repeatedly in the special features, the film is infused with Surrealist and even Dadaist elements, and while the nudity may have been included for commercial reasons at the behest of producer Sam Selsky, it lends the film a strange and melancholic eroticism that would quickly become a Rollin signature. In many ways, the film is also a reflection of the freedom of expression and rejection of societal convention that was central to the counterculture movement of the era, while the influence of the Beat Generation can be seen in the look of The Vampire Queen’s two male henchmen, who are played by the film’s credited art director Alain Yves Beaujour (he did much more than this – see his interview below) and Rollin’s brother Olivier.

The Rape of the Vampire is a tough film to easily categorise, despite the genre labelling suggested by its title. It’s a vampire movie, yes, but not like any you’re likely to have seen, even in Rollin’s later filmography. Despite my confusion, I still found much to admire even on that first disorientating viewing, as for all its improvisation, experimentation and discombobulated structure, I still found it astonishing that this was a first film for everyone involved. Yes, there is iffy acting here and there, but technically the film looks every inch the work of experienced professionals. The often striking framing and lighting of Guy Leblond’s monochrome cinematography makes evocative use of the castle and beach locations, and even when filming in a real psychiatric hospital, where creative use of lighting was doubtless restricted, Leblond delivers the cinematic goods. Intermittently, however, he moves into a different league entirely. When Thomas is attempting to cure the sightless girl’s psychological blindness, the camera circles around them dizzyingly in the sort of shot that Brian De Palma would later grasp with both hands. It then come to a smooth rest rest with such perfect timing and framing for the character move that follows that I genuinely can’t imagine the shot being done better by even the most experienced camera operator today. The creativity doesn’t end there, being quickly followed by another sublimely executed shot, as the girl breaks away and runs for the door, and the camera travels with her and invisibly switches from objective to subjective, then back to objective again without a bump or a cut. Seriously, this is top-flight teaching material here.

How you react to the film may depend on your tolerance for the sort of rule-breaking and fragmented storytelling that fans of experimental cinema will take in their stride and likely warm to without any extra encouragement from me. If you hate it, I won’t fault you, as it just won’t work for everyone, but over the course of what has now been three viewings and the slew of special features that accompany this presentation, I kind of fell in love with the film and the spirit in which it was made. For Rollin fans, it’s essential viewing, as this is the film that effectively gave birth to his feature career, and thematically it sets the tone and many of the themes that would characterise the poetic, slyly erotic, often melancholic genre works for which he would soon become known. And it may be a small thing, but the film also has some of the most convincingly believable vampire fangs that the genre has to offer. Fans of more traditional vampire movies and those who prefer their stories to be told with focussed clarity may struggle here, but if you’re up for the challenge, Rollin delivers more in this wild, creative, and seductively playful first feature than you’ll find in many a mainstream genre movie of today.

One of the things that struck me most when I first started watching films on Blu-ray was that well restored black-and-white films tended to look even more striking than their colour counterparts. Maybe it’s down to unconscious expectations, built from years of growing up watching shabby prints on TV, that older films will look inferior to a modern ones by default, but a great Blu-ray transfer of a first-rate restoration of a monochrome film has a beauty to its greyscale that I find utterly seductive. Now we have the even higher resolution of UHD, which when combined with the wider colour and contrast gamut offered by HDR, has the potential to make these films look even more impressive. Can you see where this is leading?

The result of a new restoration from the original negative by Powerhouse Films, the transfer on this 4K UHD with Dolby Vision HDR is downright glorious. A low budget film The Rape of the Vampire may have been, but it was shot on 35mm by someone who knew how to light and frame and set the exposure to achieve the best results, and the restoration and transfer really showcase his work. The sharpness and level of detail is often superb, and the contrast has a wonderful range, with solid blacks and clearly defined highlights, and the best material (there is some slight variance) boasts a generous, HDR-assisted greyscale in-between. There is a fine film grain that only becomes coarser on a couple of interior shots, and while there is some very light flickering in places, it’s never distracting. As you would hope, just about every trace of dust and damage has been eliminated. There are a couple of shots where the focus is soft (a shot of the two doctors as they evaluate their work loses some sharpness as the camera zooms in), but this was clearly a slight miscalculation on the focus during the shooting stage. A fine film grain is visible throughout, and does occasionally coarsen a little, suggesting an occasional switch of film stock to shoot in lower light. A phenomenal job.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is in decent shape, and while the tonal range is not exactly generous, and there are a couple of moments when the music comes close to distorting, the dialogue is always clear, and the score for the most part sounds fine. Again, there is no trace of serious wear or damage.

English subtitles kick on by default but can be switched off either on the main menu or on the fly. As far as I’m aware, there are no specific subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired.

Audio Commentary with Jean Rollin

When you elect to play this commentary, a text screen appears informing you that it was recorded for 2007 DVD release and that the original mix was mistimed, with the result that Rollin’s comments were often out of sync with the material he was referring to. In an effort to correct this, the fine people at Indicator have invested what I can only imagine were long hours of work to bring Rollin’s words and the on-screen images into synchronisation. As they did not have access to the raw, unmixed commentary, this means that the soundtrack of the film, which can still be heard playing faintly in the background, is now sometimes out of sync with the picture. Frankly, this matters not a jot, as the commentary is the key focus here, and having sat through my share of mistimed commentaries and been frustrated by every one of them, I salute the work that Indicator has done here. Seriously, bravo.

So after all that effort, is the commentary worth it? Most definitely. Rollin is an engaging storyteller and has plenty of stories both factual and anecdotal to share about the film and its making. He states up front that everyone involved was making their first feature (or in his case, his first complete feature – see below) and describes himself and his collaborators as amateurs who improvised much of what we see on screen. Areas covered include American producer Sam Selsky’s insistence on the inclusion of female nudity to enable him to sell the film, the castle location and Rollin’s beloved beach, the night-time duel scene lit solely by magnesium torches and smoke bombs, the low-budget execution of the striking circular tracking shot, shooting in an actual hospital, the influence of the films of Louis Feuillade (Judex, Les vampires), and much more. He addresses the negative audience reaction to the film with good humour, with the sudden location switch from the castle to the beach apparently being a particular point of outrage for an audience full of agitated viewers “who had already endured half-an-hour of this crazy film” and were apparently shouting at the screen at this point. The ending, where one of the characters walks quoting Gaston Leroux, apparently drove them crazy. An indicator of the film’s low budget is provided when Rollin admits that he wasn’t there for a couple of scenes because he had to go off and collect his unemployment benefit. There’s tons more of real interest here.

Audio Commentary with Tim Lucas

This second commentary by film expert and author Tim Lucas initially sounds as if it’s going to be a rather dry and academic affair, but the sheer range and depth of Lucas’s knowledge of the genre, coupled with his always interesting readings of scenes and characters, quickly makes this an essential listen. In tune with other commentators, he describes the film as both Surrealist and Dadaist, but also calls it the most impressionist vampire film since Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932). Hesuggests it was influenced in part by Jules Michelet’s 1892 book La Sorcière (The Sorcerers), finds connections to Brian De Palma, David Cronenberg and aJean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville, and even corrects a cast detail mistake on the film’s IMDb page. His analysis of the film is of particular interest, noting that it sets out to deconstruct the things that frighten us, that it can now be seen as a metaphor for post-traumatic stress disorder, and that the story revolves around well-meaning people who came to solve a problem, only to then become the problem themselves. I’m just scratching the surface here, and there’s so much more of value, though there are a couple of comments that suggest Lucas hadn’t previously heard the Rollin commentary when he recorded his – his analysis of the slightly surreal image of the vampire women carrying torches whilst walking in daylight is undercut a tad by Rollin’s revelation that the grading of the shots is off and it’s meant to look like night.

Jean Rollin Introduces ‘The Rape of the Vampire’ (2:33)

Sourced from a previous DVD release and clearly filmed at the same time as the introduction included on Indicator’s UHD release of The Shiver of the Vampires, a reclined Rollin provides and overview of the film in English, while an unidentified figure sits beside him holding a ghostly white mask over their face. He reiterates here his view that this was an amateur production, that everyone in the cast and crew was working on a feature film for the first time, and that many of the scenes were not scripted but improvised. He outlines how the original 45-minute film was expanded to feature length, and how the it outraged audiences but was ultimately a financial success that allowed him to make his next film.

Fragments of Pavement Under the Sand (31:54)

A retrospective documentary about the making of The Rape of the Vampire by Jean Rollin’s personal assistant, Daniel Gouyette, built around interviews with Rollin, editor Jean-Denis Bonan, actor Jean-Loup Philippe, and critic Jean-Pierre Bouyxou, and very much in the style of the one he made on The Shiver of the Vampires (which is included on the Indicator UHD and Blu-ray of that film). A lot of interesting ground is covered, primarily by Bonan and Rollin, who are without question the lead interviewees here. Bonan recalls first meeting and becoming firm friends with Rollin whilst working in the editing department at French newsreel production company, Les Actualités Françaises, and the making of Rollin’s debut short film The Far Countries (Le Pays lions, 1965 – see below). He then moves on to the production of Rape of the Vampire, whose lack of clear plot and natural flow to the footage simultaneously created challenges and multiple opportunities for him as an editor. Rollin acknowledges the importance of director Robert Hossein and the Nouvelle Vague for opening the door for new young filmmakers at a time when you usually had to be over 50 to direct, but admits to having little interest in the films being made by this emerging talent and going his own way instead. He recalls throwing out his initial plans for Rape of the Vampire just a couple of days into shooting and realising that he couldn’t make a ‘normal’ film after watching rushes of the villagers, all of whom were played by crew members (Rollin included). Only when he watched audiences screaming with outrage in the cinema did he realise that the plot was nonsensical and that he’d made something “hybrid and strange.” Jean-Loup Philippe pops up briefly a couple of times to comment on his performance and reveal that Rollin used to sneak into cinemas incognito to watch the audience reaction, concurring with his colleagues with the understatement that “people didn’t like it.” Of particular interest when it comes to audience reaction is Jean-Pierre Bouyxou, who recalls looking forward to seeing the film, only to emerge from the screening believing that it was “extremely terrible, amateurish, dumb, without an ounce of poetry.” Only when revisiting the film years later did he realise that he’d missed the point and that initial reaction was shaped by the film’s revolutionary nature, suggesting that it “threw a Molotov cocktail” into middle-class bourgeoise thinking and was a slap in the face of ‘decent’ societal values. He now describes it as “a near masterpiece” and claims that all those who hated the film on its release have since changed their minds about it. Fascinating stuff.

Cast and Crew Interviews takes you to a sub-menu containing five archive interviews.

Jean Rollin on ‘The Rape of the Vampire’ (4:23)

A brief chat with Jean Rollin, conducted by Joshua T Gravel at the 2007 Fantasia Film Festival, in which he touches on why he prefers vampires to other classical monsters, confirms that the producer Sam Selsky told him he could do whatever he wanted as long as he included some female nudity to enable him to sell the film, and notes the influence of surrealist painter Paul Delvaux on his compositions.

Jean-Denis Bonan: Jean Rollin L’Effervescence (39:30)

The film’s editor, Jean-Denis Bonan – who here is identified here as director, editor, sculptor, painter, poet, and friend of Jean Rollin – looks back at first meeting and befriending Rollin, the impact of the May ’68 student uprising (a memorable news footage shot of which is frozen to identify Rollin in the crowd), the script Rollin wrote for Nicholas Devil’s comic strip Saga de xam, and the artistic collective that grew up around Devil. He talks about Rollin’s first short film, The Far Countries, his own deliberately provocative short film Tristesse des anthropophages (1966), and what would have been Rollin’s first feature L’Itinéraire marin had the funding not dried up during production. He then moves on to Rape of the Vampire and Rollin himself, about both of which he speaks revealingly and at some length. He also comments on the film’s release and the negative audience reaction, the role of the seashore in Rollin’s films, and how Rollin’s melancholia manifests itself in his compositions. The interview is bookended with footage of Bonan completing and talking to a doll of his own making that represents Rollin, who by the time of this interview had clearly passed away.

Jaqueline Sieger: Je ne regrette rien (12:27)

In a 4:3-framed 2007 interview sourced from Encore Filmed Entertainment, Jaqueline Sieger, so enigmatic as the Queen of the Vampires in the film, looks back at being asked to play the role when she was working as an instructor in a psychiatric hospital and thinking “Why not?” at a time when people were experimenting with new experiences. She recalls being given a sum of money by Rollin to create her own costume and enjoying picking up exotic accessories at flea markets, and reveals that she did some colouring of above-mentioned comic strip by Nicolas Devil, who helped her with the design of her costume. When she picks the scene in which she stabs a sacrificial victim and licks the blood from the knife as one of her favourites, Jean Rollin himself is revealed to be in the room, interrupting the interview to show her a poster for Extrême Cinéma featuring that very image.

Alain-Yves Beaujour: The All-Rounder (17:58)

Another 2007 interview sourced from Encore Filmed Entertainment, this time with Alain-Yves Beaujour, who plays the bearded servant of the Queen of the Vampires, which turns out to be a minor aspect of his work on the film. Both he and a once again off-screen Rollin confirm that he did a bit of everything, including writing much of the dialogue, working as production manager and set dresser, choregraphing the duel scenes, and even redubbing American Doc Moyle’s dialogue as the Lord of the Manor. He outlines the process of making the vampire statue in the Grand Guignol Theatre finale, explains why one of the bedsheet wings has clearly not been ironed (“I can’t unsee that now”), and has an anecdote about how exhaustion was causing them all to hallucinate, one that that voice of Rollin then expands on.

François Tusques: Parallel Routes (11:25)

This third Encore Entertainment sourced interview is with François Tusques, whose free-jazz-inspired, almost avant-garde score is so integral to the tone of the film’s second part. Unsurprisingly but usefully, he discusses his approach to composing the music, the idea being to improvise freely but in a way that related to the imagery, as well as contributing the gloomy atmosphere that was the in spirit of the vampires in the film. He talks about his work since (composing music for TV, he reveals, pays badly), and admits to being uninterested in the way music is used in American movies, believing that the score should tell a story that is parallel to the film. As an example of a score he admires, he cites the one that accompanies Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt, which Georges Delerue apparently composed without watching the film itself.

Virginie Sélavy: Indelible Impressions (8:15)

Slightly tricky, this one. Author and film historian Virginie Sélavy provides a concise overview of the film and its production, but by the time I got to this particular special feature I’d heard the vast majority of what she has to say before, often outlined in greater detail and by those directly involved in the production. Thus it’s probably best to watch this one first – it would probably make for a sound introduction.

Alternative Scene (2:10)

An alternative edit of the sequence in which a tied-up Thomas pleads with an already operated-on vampire hospital victim (Yolande Leclerc) to get up from the operating table and free him. This has less nudity than the version in the film, but a stronger focus on the woman’s expression makes it feel more threatening (Leclerc was apparently a patient at the psychiatric hospital at which they were filming – in his commentary, Rollin questions the wisdom of handing her a scalpel to cut Thomas’s bindings).

Super 8 Version (16:39)

It’s always rather fun to see how distributors of these cut-down 8mm editions could compress a feature-length movie into the running time of a particularly brisk short, and this one is no exception. All but ignoring the film’s second part, from which it borrows only to provide a vampiric take on a romantic ending, it skips through the comparatively shorter first part without a soundtrack, with dialogue occasionally represented as French intra-titles (for which optional English translations are provided). It does tell a similar tale to the first part of the feature-length version, but does so without a whisper of nuance or character detail, and while it tries to take more straightforward approach to storytelling, occasionally it manages to be even more bemusing – when two of the vampire women fight a duel to the death, the reasons are left to us to pluck out of thin air.

Theatrical Trailer (4:30)

Not the easiest film to sell as a commercially viable genre work, so this trailer doesn’t try, instead almost randomly juxtaposing disconnected sequences to François Tusques’ free jazz score to create a sense of steadily building madness. A caption does announce it as the first French vampire film, which turns a convenient blind eye to Roger Vadim’s 1960 Blood and Roses [Et mourir de Plaisir].

There are two Image Galleries, both of which primarily consist of monochrome photographs of variable but sometime pristine quality. Original Promotional Material has 112 screens of productions stills, plus what looks like a ticket to the premiere, press booklet pages, a VHS sleeve, and the film’s memorable poster. Behind the Scenes has 90 screens of production shots showing the actors between takes and Rollin and his crew at work. Includes a couple of photos revealing how the eye-catching circular track was achieved.

The Far Countries (1965) (16:25)

A real coup of an inclusion this, The Far Countries [Les pays loin] being an early short film by Jean Rollin made before The Rape of the Vampire. It’s a work that is referred to repeatedly in the special features, so it’s great to be able to see it, particularly looking as good as it does here – this has also been restored from the original 35mm negative for this release. As it starts, an unnamed man appears to be running from someone or something and seeking refuge in alleyways between run-down and decrepit buildings. Eventually he meets up with a woman whom he has only recently met after the two of them found themselves inexplicably transported to a city they simultaneously seem to recognise and not know the name of. Almost everyone they meet and ask for help speaks a different language, and when the man recognises a house as belonging to a friend, he barely has time to reveal his presence before the friend urgently puts on his coat and leaves the building, leaving the man in the company of a woman who also speaks an unknown language. A fascinating, surreal science-fiction infused piece that has an authentically dreamlike feel, resembling as it does those frustration dreams where you can’t quite get to where you need to go or find the person you are supposed to meet, and set in a place that bears little resemblance to the location that you somehow know it is. In the early scenes, an argument could be made for seeing the film as a reactionary response to multiculturalism, but this is soon quashed by the warm welcome the couple receive from the location’s black community, and a comment by the departing friend that suggests that the man is also an immigrant and that French is not his native language.

The Far Countries Jean Rollin Audio Commentary

I’m unsure when this was recorded and by whom, but Rollin is here joined by an unidentified male host, who most effectively prods him for information on the making of the film, which we learn early on was shot in an area of the Belville neighbourhood of Paris whose fascinatingly run-down buildings no longer exist. Rollin confirms that the cast are all friends, friends of friends, or locals invited to be in the film, that it was shot at weekends on a borrowed 35mm camera and otherwise self-financed, and that when it was finished, a lack of distribution meant that nobody saw it. Both men praise the monochrome cinematography of Georges Delaunay, who has since gone on to rack up over 100 film and TV credits.

The Far Countries Image Gallery

A gallery of 48 production stills, including some welcome behind-the-scenes shots, plus a poster for a screening that the film did receive, all of which are credited to Gilbert Gibdouny and the Cinémathèque de Toulouse.

L’Itinéraire souvenir (2018) (27:43)

Adding to the gloriously completist feel of this release is Rollin’s 2018 reconstruction of what would have been his first feature had the funding not dried up and the laboratory not lost all of the shot footage. This is created through a montage stills taken during the production, which are intercut with film extracts, newly shot footage, and close-ups of the screenplay. The soundtrack is driven by a descriptive narration and dialogue read by actors Jean-Loup Philippe, Mickael Collart, Helene Polsky and Maurice Briere, and is backed by music and a subtle and evocative use of sound effects, which collectively paints an intriguing picture of the film that might have been.

Two bachelors named R.J. and Denis find themselves in the same train compartment, and after a frosty first encounter they unexpectedly become friends, and by chance hook up with a younger girl named Sophie, whom they invite to join them on a trip to Brittany to visit Denis’ uncle. There’s a definite Novelle Vague vibe to the tale, though it is also has the air of a visual poem and is touched the melancholia that hangs over so many of the characters in Rollin’s cinema. It marks Rollin’s first cinematic trip to his treasured Plage de Dieppe beach location, and as is pointed out in the special features, had the work been completed and released, his film career might have taken a different path. A fascinating and most welcome inclusion.

De la grève: A Short History of L’Itinéraire marin (6:55)

Jean-Loup Philippe, who plays Dr. Samsky in Rape of the Vampire, recalls quitting acting at a young age to start a poetry theatre group, meeting Jean Rollin when he came to one of their shows, and being asked by him to play role in what was to be his first feature, L’Itinéraire marin. He confirms that the film was never completed due to a lack of funding, and claims that an actress he prefers not to name walked off the production anyway when she found out it was an unpaid gig. Jean-Denis Bonan chips in to reveal that he only saw a short clip of the film and that he really loved it, and closes by stating that if the lost rushes are ever discovered, he’ll edit them for free. The soundtrack is Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo and is of excellent quality, with clear frontal separation of the actors’ voices during conversations, making it easy to identify which character is speaking at any time.

Also included is a Limited Edition Exclusive 80-page Book, which opens with separate credits for both parts of the film, then launches into an essay by film critic Beatrice Loayza, who recalls first discovering the imagery of Jean Rollin on Tumblr, of all places, before moving on to a fascinating look at Rape of the Vampire and its director. Next up, we have the liner notes from the Encore Films 2007 DVD, written by Rollin himself, who takes a thorough and compellingly detailed look back at the making of the film, one that compliments, expands on, and adds to the information delivered in his commentary rather than repeating it. He talks about the eroticism in his films, admits that, "I thought that my screenplay was perfectly constructed and clear, but I was the only one who did," and "Once the film was edited, everybody (but me) had to face the fact that it was impossible to understand any of it," and provides some new detail on the release and the audience and critical reaction to it. This is followed by a 1996 interview with Rollin by Peter Blumenstock for Video Watchdog magazine that covers Rape of the Vampire and Rollin's subsequent film career, all of which makes for enjoyable and interesting reading. After this, we have the credits for The Far Countries, and a 2005 piece by Rollin for the Encore Films DVD liner notes in which he revisits the making of the film. The book is handsomely illustrated, and concludes with details of the restoration, which are always welcome.

The film that effectively launched and shaped Jean Rollin’s feature film career is given the best of royal treatment by Indicator on this fabulous UHD release, The restoration and transfer are both terrific, and the special features have everything you could really want and more. The film may still divide audiences even today, but I wanted to hug it, and seeing it looking this good and with this level of background detail proved to be the perfect introduction. Highly recommended.

|