|

There are times when a title technically counts as a spoiler but has either been chosen to help get the punters through the door, or because it seems to be the most logical or even the most poetic choice. Take Two Orphan Vampires [Les deux orphelines vampires], the penultimate work in this particular subgenre by one of its most creative exponents. There are two rather neat twists in the first 18 minutes, but the second of these (that the two orphan lead characters are vampires) only counts as a twist if you go into the film not knowing the title, its genre, or the name of the director. The first twist is a different story, and loath though I am to reveal it, it’s nigh-on impossible to avoid doing so if I’m going to discuss the film on any more than a one-paragraph precis level. And Two Orphan Vampires deserves so much more than that.

The film opens in undramatic manner in an orphanage office, where the Mother Superior (Anne Duguël) and her assistant, Sister Marthe (Nathalie Perrey), are telling middle-aged Doctor Dennary (Bernard Charnacé) about two of the teenage girls in their charge, Louise (Alexandra Pic) and Henriette (Isabelle Teboul). They tell him that the girls lost their ability to distinguish colour in childhood, which eventually degenerated into total blindness. When the girls arrive, white canes in hand, the doctor examines them and confirms their condition. The nuns then drop some heavy hints that a man like the doctor might consider adopting and taking care of them, and possibly even find a cure for their condition. The suggestion of a possible cure momentarily excites the girls, but they are quickly brought down by their expressed belief that it is God’s will that they should never regain their sight.

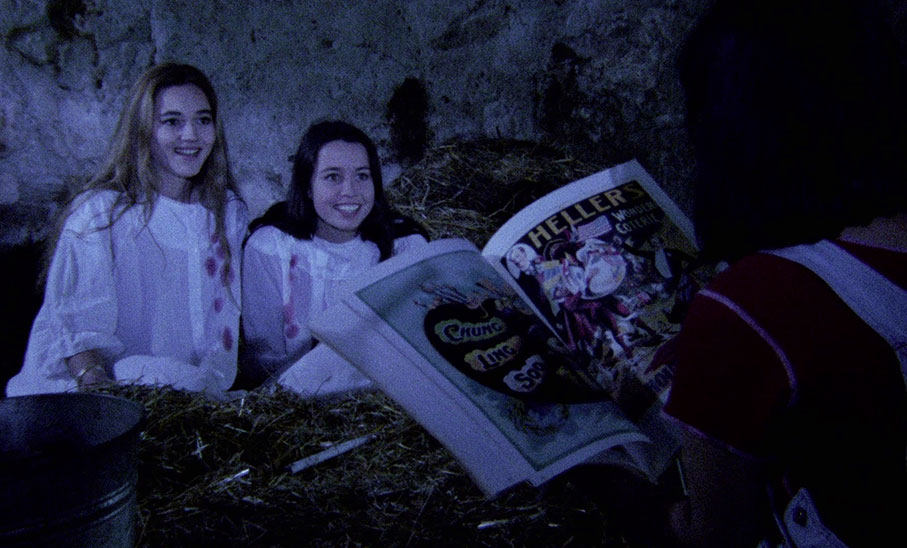

That night, as Sister Marthe prays that the good doctor will adopt these two patient, gentle and innocent little martyrs (an intriguing choice of words on her part given their true nature), Louise and Henriette wake giggling from their faked slumber and look out into the night towards a cemetery to which they then quietly but cheerfully make their way. So were they faking their blindness after all? Not according to the doctor who examined them, and he should know. The answer is supplied in snippets and is an intriguing twist on established vampire lore, the suggestion being that around the time they hit puberty they were stricken blind, but only during the daylight hours. When night falls, however, their sight is restored, but they are only able to see the colour blue. It’s an inventive take on the nocturnal power of the vampire as envisioned in that godfather of vampire novels, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, whose titular Count was able to move freely around in daylight, but with his powers severely diminished. The choice of blue as the colour they are able to see is also interesting, being the symbolic colour of moonlight, and later cited by filmmaker Derek Jarman as the only colour he was able to see once Aids – which by the late 1980s had become a favourite subtext for the vampire movie – had almost completely robbed him of his sight.

As Louise and Henriette hold each other in the cemetery, dressed like wandering spirits in their white nightgowns, they recall the many times they have died and returned to life, only to the fall victim to another “mishap” and die violent dead at the hands of others. As they struggle to remember the specifics of these previous lives, they recall a time when they killed and drank the blood of a painter (Martin Snaric) on New York’s Brooklyn Bridge, a distant location that suggests that they do not stay in one place for too long before fate or expediency forces a relocation. They revel in the night air of the cemetery, and after dancing with each other to music wafting from a nearby open window, they feed on the blood of a dog that innocently comes to their deceptively friendly calls.

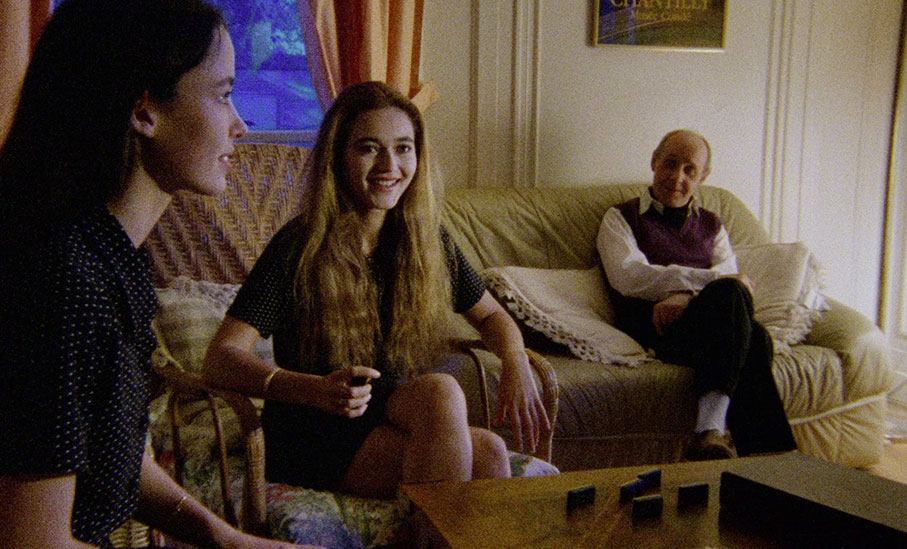

If the now suspect concept of a middle-aged bachelor adopting two teenage girls on nothing more than a nod and a wink from a couple of orphanage nuns concerns you, be comforted by the news that his intentions really are honourable here. After driving the girls to their new home and guiding them to their room, he kisses each of them lightly on the forehead in a show of fatherly affection and retires to his room for the night, blissfully unaware that sleep is the last thing on the minds of his two adoptees. Again they venture out, this time preying on a lone carnival worker (Brigitte Lahaie) who mistakes the girls for pranksters and chases them around a circus tent with a whip, only to then pay the price when they turn the tables and leap upon her. The doctor remains blissfully unaware of their nocturnal activities, and so trusting is he that he feels comfortable leaving them alone in the house for a night while he attends an out-of-town medical conference. The girls relish the freedom this gives them, and as soon as the doctor departs they make their way to a large city cemetery, where they sleep until the arrival of nightfall allows them to hunt that evening’s prey, but the impending threat of capture leads them to a strange encounter with another of their kind.

The case has been made – and indeed is made in the commentary on this disc – that if you come to Two Orphan Vampires after feasting on Rollin’s early genre works, then you might be setting yourself up for a disappointment. This film is longer and slower paced than the likes of The Shiver of the Vampires (Le frisson des vampires, 1971), Requiem for a Vampire (Requiem pour un vampire, 1971) or Lips of Blood (Lèvres de sang, 1975), and the nudity, eroticism and bloodletting of the earlier films is carefully rationed here. Indeed, Two Orphan Vampires has more in common tonally with the director’s 1989 made-for-TV movie, Lost in New York [Perdues dans New York], a poetically surrealistic work that also features dual female leads and is regarded as one of the director’s most personal films. As is made clear in the special features, this film was also dear to Rollin’s heart, being an adaptation of two of his own vampire novels and the first genre film where he did not feel pressured to spice up the gore or the nudity to give it a more commercial appeal. Indeed, the vampirism is secondary here to a story of two outsiders who are probably sisters (this is never confirmed), and whose relationship is now so strong that it has become almost symbiotic – you genuinely cannot imagine one surviving for long without the other.

Where the film does share DNA with Rollin’s earlier works is its semi-surrealistic adult fairy tale feel. This is most evident in the humanoid creatures that the girls encounter in their wanderings, whether it be the She-Wolf (Nathalie Karsenty) who hides in a deserted train yard from the dogs that recognise her for what she is and attack her, or the Ghoul (Tina Aumont) who wanders the countryside and claims to draw nourishment from the earth. Most striking of these is the large-winged Bat Woman (Véronique Djaouti), whose graveyard lair the girls enter when fleeing their pursuers and who offers them safe haven for the night. It’s characteristic of Rollin that this multi-stranded subculture is exclusively female, if a seemingly sad and lonely one. All three of these creatures live and hunt in isolation, each offering food for thought to the two girls but ultimately then sending them on their way. Whether they all are what they initially seem is another matter. The Bat Woman’s gargantuan wings, vampiric fangs, and ability to sleep whilst standing suggest that she is the real deal, but the She-Wolf and the Ghoul display none of the physical characteristics of the creatures they claim to be, and the She-Wolf even reveals that she recently escaped from a clinic in which she was held because she was considered by others to be mad. Then again, if she only transforms into a wolf when the moon is full, as is the way with the werewolves of legend and genre movie lore, she would at other times appear in human form.

This brings me to a viewpoint expressed multiple times in the commentary by David Flint and Adrian Smith, who propose that this is actually a story of two troubled and mixed-up girls who merely fantasise about being vampires. I get where they’re coming from, but for me this reading strips the story of some of its folk tale magic and dilutes the effectiveness of its subtext. At its best, it narrows elements of the film – those that comment on society, social interaction and what it means to be different from those around you – down to the girls’ anxieties. At its least inspiring, it casts them – and by association their fellow creatures of the night – as nothing more than embodiments of characters they read about in the mythology books that they so adore. To back up their claim, Flint and Smith cite George Romero’s masterful Martin (1977), where the ambiguity over whether the titular lead character really is a vampire or simply a seriously messed-up kid is never confirmed one way or the other. But when we see Martin kill to drink blood, his actions are not those of the classical vampire but a calculating serial killer, which openly invites us to read the film both ways from the opening scene. In Two Orphan Vampires, the girls are shown biting the chest and necks of their victims with elongated fangs, so if they aren’t actually vampires, then everything vampiric that they do and all of the creatures that they meet are a fantasy on their part. Quite apart from the fact that this would mean that both girls are simultaneously experiencing the exact same illusions, this takes the film dangerously close to the dreaded “it was all a dream” territory. Sorry, no sale.

Except…

There’s one scene, a crucial one that I can’t discuss without delivering a sizeable spoiler, that only really makes sense if there is something to Flint and Smith’s reading. If you want to trust me on this and avoid having a late film plot point ruined (if so, definitely don’t watch the trailer before the film), then hop past the following paragraph or click here to do so automatically. For those who’ve seen the film, or who want to hear the evidence, regardless of the spoiler, feel free to read on.

The scene in question kicks off the film’s final act and begins when Doctor Dennary comes downstairs one evening to discover that Louise and Henriette are not blind after all. They blag their way out of it with tales of a small but miraculous improvement that they didn’t want to tell him about until they were sure it was not temporary, but then decide that in order to be completely free they have to kill their new guardian. Surprisingly, they don’t bite him and drain him of his blood as you would expect of a pair of vampires, but instead put him at ease in the kitchen so that Louise can then stab him in the back with a kitchen knife. And here’s the thing. When the time comes for Louise to do the deed, she’s clearly traumatised by the prospect of having to see it through, hesitating in her actions and having to be urgently goaded on by the nearby Henriette. The whole scene reminded me of supremely uncomfortable climactic scene in Peter Jackson’s 1994 Heavenly Creatures (1994), another tale of two girls whose close relationship and fantasy daydreaming ultimately lead to murder. It also it left me with a couple of questions that I can’t comfortably answer if I reject the notion that Louise and Henriette are fantasists. If they are vampires and have killed many people to feed of their blood by biting their victim’s throats, why choose to murder the Doctor with a kitchen knife? And why is it that when she is preparing to do so, Louise reacts like a teenager who has never committed a single violent act in her life and is suddenly confronted with the horrible reality of what it means to actually take a person’s life? It’s also worth noting that religion plays no significant role here, and certainly does not represent any sort of threat to the girls. They are initially sheltered by nuns in an orphanage and have a crucifix on their bedroom wall that does not affect them in any way, and they even accompany the good doctor to church, not the most vampire-friendly of locations. Maybe the learned Flint and Smith are onto something after all.

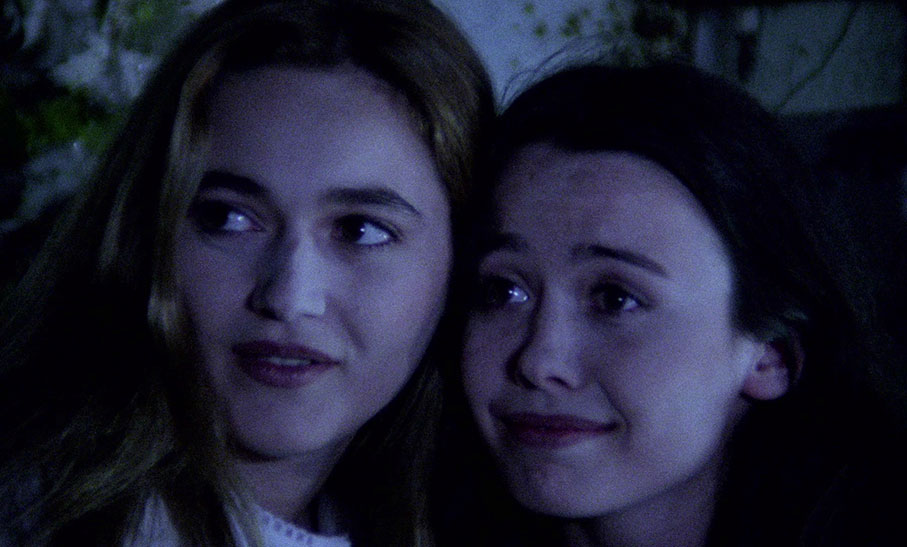

Ultimately, it matters little how you choose to read it as long as you buy into its manufactured reality, and this, for me, proved one of the film’s real strengths. Leading the way here are lead actors Alexandra Pic and Isabelle Teboul, who absolutely sell the bond between Louise and Henriette as touchingly real, which is sometimes at its most effective in almost throwaway moments. A prime example occurs in the New York flashback, when after killing the man on the Brooklyn Bridge, the two run through the streets with their long hair, loosely flowing skirts and circular sunglasses like excited hippies at a music festival, pausing on the way to laugh and playfully wipe the blood from each other’s lips. These two really are the heart of this film.

Visually, the film lacks the multi-colour vibrancy of Rollin’s early work, but that was clearly a deliberate decision on the part of Rollin and cinematographer Norbert Marfaing-Sintes. While the daylight scenes have a naturalistic look, those set at night are lit and filtered to appear to us as they would to Louise and Henriette, being drained of almost all colour except a dominant blue. It's a bold but strongly mood-defining choice, though does vary a little depending on the location, with the gentle lighting of the early cemetery scene giving way to harsher filtration on locations where lighting the scene artificially was simply not an option. The unhurried pacing has clearly proved a problem for even some Rollin fans, but for me it works for the tone of a film whose plot is secondary to its haunting vibe. This is further enhanced by a superb score from composer Philippe D'Aram, which blends traditional instruments with synthesisers and ethereal choirs to unsettling and intermittently eerie effect – the music that accompanies the girls’ first encounter with the Bat Woman transforms an already strong scene into something magical.

Others clearly disagree, but I was mesmerised by Two Orphan Vampires. As a lifelong outsider (where do you think this site got its name?), I found it oddly easy to identify with the two girls despite their murderous actions, emotionally connecting their inability to conform, and moved by how genuine the bond between them feels. Just how you read the final scene will depend on which interpretation of the film works best for you, and despite initially rejecting the notion that the girls were fantasists who dreamed of being vampires, the sheer honesty of emotion expressed in that sequence had me choking back tears. I have a feeling that if I was to rewatch it with the conviction that they were just a pair of tragically messed-up teens, those suppressed tears would start to freely flow. For some, the film’s leisurely pace, low action quota, and rationing of the nudity, gore and eroticism of Rollin’s earlier genre films will be a problem. It's definitely a film out of its time and won’t work for everyone, but as far as I’m concerned, it fully deserves to be ranked alongside the director’s best.

I’ve not been able to definitively confirm this, but I have a strong suspicion that Two Orphan Vampires was shot on 16mm film, a suspicion that a couple of things in the special features seem to support. Firstly, there are is a photo of the New York location shoot that includes the camera, which bears more than a passing similarity to a 16mm Arriflex that I once shot a film on. If it is a 35mm camera, it’s an uncharacteristically small one. The second occurs during the Memories of the Blue World documentary, when Véronique Djaouti Travers briefly mentions a 35mm blow-up, a process only really necessary when the format that you filmed on was dimensionally smaller than the then 35mm projected standard. This would explain the slightly more pronounced grain in some shots (the slow pan of the train yard, for example, where the higher resolution also betrays a small smudge on the lens), and a sharpness that doesn’t quite hit the expected 35mm heights. I’m not knocking the film for what is still an attractive low budget aesthetic, as the detail here is still nicely defined, and the film grain is, for the most part, is surprisingly fine for 16mm stock. Some of the imagery does present a challenge for any digital transfer, particularly when the girls encounter the Ghoul, where the subjective blue wash is combined in one shot with a graduated filter in a way that sucks shadow detail into the darkness, but this works for the scene, and the transfers on both the Blu-ray and the UHD editions cope with this without issue. Elsewhere, the colour has a naturalistic feel, particularly in the rare sunlit exterior shots, and no attempt has been made to pretty-up location shots filmed in fading light with supplementary lighting. That said, the more vibrant blues, particurlarly those visible through the windows of warmer interiors, are vividly rendered. The image is framed in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1.

In terms of sharpness and detail definition, the UHD release does not represent a substantial leap over the Blu-ray, but minor improvements on this score are still clearly evident, something is particularly true of the sunlit exterior sequences (when Doctor Dennary and the girls exit the church service, for example). Where the UHD once again scores over the Blu-ray is in the implantation of HDR, which results in a subtler contrast range whose improved shadow detail allows the image to be darkened just a notch, which makes the day-for-night exterior shots feel more authentically dusk-like. Colours are also more pleasingly rendered here – again, the effect is subtle but definitely visible.

The original French language soundtrack and the English dub prepared for British and American markets are available in Linear PCM 1.0 mono on both the Blu-ray and UHD discs, and although lacking the tonal breadth of more modern films, the dialogue is always clear, the music very nicely reproduced, and there is no distortion or obvious traces of damage or wear. Obviously, the original French language track is the way to go for us purists, and while Isabelle Teboul claims to really like the English language dub, for me, the middle-class elocution lesson accents of the replacement voices just do not suit the personalities of the two girls.

The Setup menu has options to play the film with the French language track with or without English subtitles, or with the English language track with or without English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired. Both tracks can be switched on or off at any time.

Audio Commentary with David Flint and Adrian J Smith

Editor of The Reprobate David Flint teams up with Adrian Smith, who runs the Movies and Mania website, to discuss a film they both admit to being disappointed by on a first viewing but have warmed to over time and now hold in rather high regard, despite still having issues with aspects of it. Subjects covered include the lead actors, the music score, the locations, the sad pall that hangs over the film, the influence of surrealism on Rollin’s work, the scenes filmed by assistant director Jean-Noël Delamarre when Rollin was incapacitated by kidney dialysis, the higher quality evident in the porn films that Rollin directed to pay the bills, and a lot more. They make a case for the importance of the UK’s Redemption Films (I’ll second that), whose DVD releases of Rollin’s work gave many of us our first exposure to key works from his oeuvre, and praise how much better actors Alexandra Pic and Isabelle Teboul are than some critics have claimed (I genuinely don't get where such negative criticism is coming from), and how convincingly they play blind. They also explore at some length the notion that the whole thing might be the fantasy on the part of the two girls, which I’ve discussed above. I did find myself in disagreement with them on a couple of points, and there are a couple of comments that I found surprising – 18 minutes before the end they question why the girls have their hair in pigtails for the first time, yet this is how their hair was styled in the opening scene and the early daylight sequences at the home of their new guardian, initially being used to differentiate the image they present to others from their nocturnal true selves, when they literally let their hair down. Nonetheless, a solid and consistently interesting commentary.

Memories of a Blue World (42:30)

A 2012 documentary on the making of Two Orphan Vampires by Rollin’s personal assistant, Daniel Gouyette, built around interviews with assistant director Jean-Noël Delamarre, actor, stills photographer and production assistant Véronique Djaouti Travers, score composer Philippe D’Aram, and actors Isabelle Teboul, Bernard Charnacé and Nathalie Karsenty. Several stories about the making of the film are related, including details of the scenes shot by Delamarre when Rollin was in dialysis, and D’Aram reveals that the film’s music budget was close to zero and explains why he was ultimately unhappy with the result. Teboul cheerfully claims that she adores watching the film dubbed in English, and Travers provides the full gruesome details of how wearing the insanely heavy wings as the Bat Woman cracked three of her vertebrae. That she still finished the scene despite being in excruciating pain – something confirmed by others – tells you a lot about her long-standing working relationship and friendship with Rollin, a man whom no-one here has a bad word for.

Jean Rollin: Infinite Dreams (35:04)

A 2002 interview with Jean Rollin conducted and filmed by Lucas Balbo and Merrill Aldighieri, who are also responsible for several of the other legacy special features here. Here, Rollin discusses the influence on his work of the Surrealist movement in revealing detail, noting the importance of painters René Magritte and Paul Delvaux, and praising Luis Buñuel and Georges Franjou as two of the true masters of cinema. In what must have been the most frustrating coincidence of his career, he almost worked for both of them as an assistant on two films that ultimately never got made. His description of the plot of the 1935 Henry Hathaway film, Peter Ibbetson – a favourite of the Surrealists – made me instantly want to see it, and I was intrigued to hear that he was never a fan of Salvador Dali, a view I remember being also expressed by my art history teacher when we studied Surrealism. When asked why he is attracted to vampire tales, Rollin replies with wry smile, “I’ve been asked that so many times I’m tempted to tell you to get the answer from a magazine,” but he provides a detailed answer, nonetheless. He also has a few interesting stories about the making of Two Orphan Vampires, including how his illness affected the shoot.

Alexandra Pic: Bonded by Blood (13:30)

A lively and hugely likeable Alexandra Pic reveals how she landed the role of Louise in Two Orphan Vampires, and how her love of fantasy and vampire literature made her jump at this opportunity, particularly as so few genre films were being made in France at that time. She confirms that she and Isabelle Teboul hit it off from the moment they met, and that they had a great time filming the New York sequence (the first to be filmed, while Rollin was back in France on dialysis), and while she enjoyed the gore, she insists that she wouldn’t do the nude scene if she were making the film now. She also has an interesting take on her character, describing vampires as asexual and cruel and Louise and Henriette as being quite literally bonded by blood.

Isabelle Teboul: Eyesight to the Blind (11:01)

A similarly bubbly and upbeat Isabelle Teboul expresses her respect for Jean Rollin for always picking the right people to work with, and for making films for little money whilst others were banging their heads against the wall trying to finance their cherished projects. She remembers New York exerting a magical hold and confirms the fun that she and her co-star had when filming there. She recalls her discomfort at filming the nude scene and provides details of the second such sequence that was ultimately abandoned after she and Pic made a convincing case against it, one that was supported by others working on the production.

The Smoking Vampires (4:00)

A handheld record of Alexandra Pic and Isabelle Teboul as they revisit the Paris cemetery in which a key scene of the film was shot, where they seem to have as much fun as they apparently did on the shoot itself. An attempt to tint a sequence in the manner of the film doesn’t quite come off, in part because the camerawork is a little too wobbly, and the whole thing is a little content-light, but the two women are so infectiously effervescent that it’s a still highly enjoyable to watch. The title comes from a moment when Pic nips off to collect her cigarettes, leaving Teboul to recall how young she started smoking and when she decided to quit.

Livres de sang (7:26)

Shot in the same session as Infinite Dreams above, here Rollin shows the interviewer and unsteady camera operator copies of the vampire novels he has written, including an English translation of Little Orphan Vampires released in the UK by Redemption, bless ’em. Also on display are some of the prizes he has won at festivals, some of which are fabulously designed.

Theatrical Trailer (2:02)

A ploddingly assembled French trailer that pushes the film as an all-out vampire tale and gives far too much away, even including the key moment from the scene that I provided a spoiler-warning for before discussing.

There are two Image Galleries, both of which are manually advanced using your player’s remote control. Production and Publicity features 42 screens of promotional images, behind-the-scenes photos, and scans from what looks like the press book. New York Location Photography consists of 81 screen of colour photos taken of the New York shoot, including a few that show assistant director Jean-Noël Delamarre standing in for the medically absent Rollin.

Booklet

Another handsomely presented booklet from Indicator, whose lead essay here is by author and professor of continental philosophy at ARU, Cambridge, Patricia MacCormack, who nicely describes Two Orphan Vampires as “a lyrical love-letter” and recalls being told two fairy tales by Rollin in his Paris flat in 2004. Her assessment of the film is fascinating and quite unlike any other that I have so far read. Next up is a 1997 introduction to Two Orphan Vampires by Jean Rollin, who describes it up front as “Certainly my most accomplished and professional film,” and praises his actors and crew. He provides some interesting background information of the film’s production, and makes it clear what a pleasure it was to work on. Following this is a report from the set of Two Orphan Vampires from the January 1996 edition of Fangoria magazine, which includes comments from Rollin, cinematographer Norbert Marfaing-Sintès, and Rollin’s partner Lionel Wallmann. Also from the same edition of Fangoria is an on-set report by Peter Blumenstock in which he talks to former porn star turned actor Brigitte Lahaie about her career in cinema and her work for directors Jean Rollin and Jesús Franco. Next, we have the entire first chapter of Little Orphan Vampires, the first of the two books on which the film is based, which was translated into English by Rollin expert Pete Tombs and published in the UK by Redemption Books. Having not read the novel, I welcomed this, but it did make me want to read more. Well you should have bought it while you had the chance! Credits for the film and details of the restoration have also been included, and the book is generously illustrated with promotional material.

For some fans of Jean Rollin’s early work, Two Orphan Vampires is disappointing for one of the very reasons I was so taken with it, that for much of its running time it doesn’t play like a vampire film at all. How you interpret it is going to be a subjective call, and it’s just possible that both readings discussed above are simultaneously valid and interchangeable, that the girls both are and aren’t vampires, a paradoxical claim hinted at in Louise’s suggestion to Henriette that they are both dead and alive. Either way, I was utterly entranced and ultimately moved by the film, thanks in no small part to completely believable performances of the two young leads. Again, Indicator has done the film proud on both its Blu-ray and UHD incarnations, and while the case for the UHD version is not quite as strong as it was for the simultaneously released Shiver of the Vampires, the case is still made, and if you are UHD-enabled that’s still the one to go for. Although this one seems to divide viewers, for those of us for whom the film clicks, this edition comes highly recommended.

|