| |

“I have a special fondness for elements that are unlike anything I’ve seen/heard/felt before. True originality is hard to find, of course, but I’m always looking for a certain frisson (be it a camera angle, a line delivery, a facial or gestural expression, a visual effect, art direction, sound design, montage or narrative structure) that evokes a genuine sense of wonder in me.” |

| |

From Writer/Director Peet Gelderblom’s own Five Word Challenge* |

Note: Director Peet Gelderblom had the première of his remarkable film on the 31st August this year in the Netherlands. It will be making the Film Festival rounds I’m sure but this is just to let you know that if I convince you to seek it out, for the moment it’s only being screened at selected festivals. You may have a bit of a wait for a disk or a streaming release. It’s well worth it…

Once upon a time, a passionate and committed filmmaker was given access to what one assumes were thousands of hours of archived film from silent classics to animated commercials, newsreels to stop motion shorts. From a carefully chosen selection of wonderfully diverse imagery, the filmmaker created a very personal work about the eternal relationship between the sexes, a relationship sailing on thunderous, choppy and rarely calm waters. It is one of very few films that was directed retrospectively, long after the original craftspeople had retired or passed on. Images are interpreted, re-interpreted by thoughtful, creative juxtapositions and the whole offers an experience that is quite unique. And did we ever live happily ever after?

When Forever Dies is not only a passionate love letter to the sublime shine, shrine and chiaroscuro shadows of cinema itself, it’s also thousands of metaphors cut into a single dynamic narrative. Despite the long-forgotten archive shots’ inevitably disparate nature, they are shepherded into an overarching history of the human animal, a goal almost mythic in its ambition. The film also tells you a great deal you might want to know about the artist himself. You might say the same about Eraserhead and David Lynch (perhaps until you actually meet him) but When Forever Dies is more than Lady Bird Johnson’s “art is a window to man’s soul”. It’s an outpouring, a release of the filmmaker’s personal vision on (of all things) the procreative human relationship and all of life that this ongoing association touches, faintly and without restraint, both subtle and gross. Let’s ignore the title’s other dual life, auditioning for a James Bond film – vying with Diamonds Are Tomorrow – and dive right into the bricks and mortar that make up this singular edifice, one with such an idiosyncratic and compelling point of view.

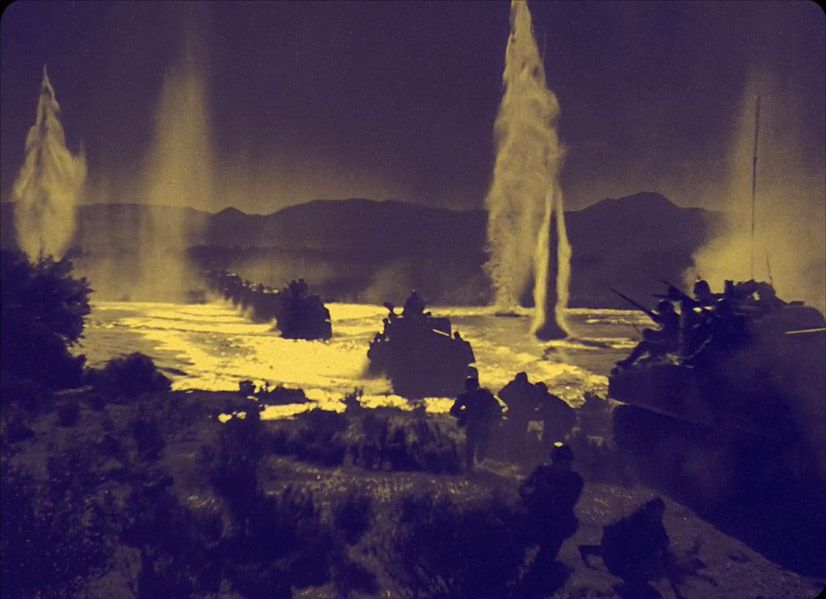

So, you’ve heard of Shakespeare’s ‘The seven ages of man…’? Here’s Peet Gelderblom’s five stages of man and woman, an epic traipse through the archives highlighting the fabled roots and milestones of our tumultuous affairs and interactions. The titles of the five sections are very telling. They are variations in light levels which has so much more to do with cinema than with evolved primates and believe it or not, that penny took its sweet time to drop… First Light, Magic Hour, Total Eclipse, Fire Fall and Afterglow… Spelled out like that, I started to feel a bit slow on the uptake. The irony is, of course, that archived film has to be preserved in the dark. All of human life is here told with the help of some extraordinary footage that usually survives in cool shadows in a vault to preserve its life. But is film only ever alive when its dappled light is dancing in front of us? When ‘Forever’ man discovers ‘Forever’ woman, Heaven and Earth would not stop his relentless march to her side. As armies sprint to find their sirens, Gelderblom intercuts sperm racing towards the maidens, every one of them seeking its moment in the ovum… I was instantly struck by an extract from the 1984 8-hour stage performance and album United States I-V by Laurie Anderson… (an astonishing live event I was fortunate enough to attend).

“If a sperm were the size of a whale, however, it would be traveling at 15,000 miles per hour, or Mach 20. Now imagine, if you will, four hundred million, blind and desperate sperm whales departing from the Pacific coast of North America swimming at 15,000 mph and arriving in Japanese coastal waters in just under 45 minutes… How would they be received? Would they realize that they were carrying information, a message?”

Now that message is sometimes thundered home and sometimes delivered with a sleight of hand that belies a range of techniques employed in the editing of this film (and make no mistake, editing is the principal film discipline on show here). Direction is defined merely as the selection of the shot. I have no idea how many shots were ‘manipulated’ in the post-production but I suspect Gelderblom wanted to maintain the integrity of the originals in some form or another. I’m happy to be proved wrong on that one. Editing is the honing of an idea. Juxtapositions are ripe with meaning and whether we are wading through uncomfortable stereotypes of the traditional women’s role or religious inspired lunacy of devilish deeds and satanic signatures, there are sublime connections to be gleaned everywhere. What Gelderblom manages to achieve more often than not is to sow a seed within seconds, have it flower frames later and then you don’t have time to mourn it before another seed belligerently buds in your mind throwing the previous one out as the outsized cuckoo chick does to its competitors, the callous goal of the impostor in the nest. The irony of this approach is that as soon as the filmmaker gives more weight and time to one single source of archive and lets its own narrative play out relatively undisturbed, it weakens his own thesis. Thankfully this happens very few times and the editorial God quickly snatches back control. There is some fun to be had spotting from where certain shots had originated (hullo, Dennis Hopper and Jane Russell!) but for the most part their stark anonymity is their strength. And therein lies one of the film’s immense joys; you literally have no clue what’s coming next. This is why spending a disproportionate time cutting from a single source is less satisfying. The film is firing on all cylinders when you have no idea what’s after the next cut. The ideas are smoothly streamlined but the range of shots on offer give a new meaning to the word ‘eclectic’. As an editor and a filmmaker myself, even I have trouble imagining what must be the infinite trim bin of the outtakes.

The film is also full of surprising parallels to our more modern film history. Forgive my ignorance at not being able to identify some of the more famous works plundered for more twenty-first century meaning (I spotted a few but this little game really isn’t the point) but there is an almost shot for shot sequence which the great Stanley Kubrick seems to have plundered for The Shining.** There is nudity and sexual activity that serves to remind us that the Hays Code took a while to impose its restrictions on cinematic art. For a short period (pre-1934) filmmakers were unfettered by moral and ethical constraints and gleefully, Gelderblom falls on this (ahem) racy footage with real gusto. Yes, it’s politically incorrect but you’re allowed to be so in art (but maybe not on Twitter). A woman reads a book titled “How To Be Happy Though Married,” (I mean, where did Peet find that?) I was ready to be taken through many iterations of that title like we were guided through the alternate horror and relief of The Simpsons’ “How To Cook Forty Humans”. There is an extraordinary scene of a woman being (presumably) pleasured by a small purple man roaming all over her body. Standing at about 8 inches tall, you can’t imagine (go on then, you probably can) what he may be up to when he’s not actually visible. My mind fractures trying to conceive in what context the original footage was created. I mean the man was purple. Do I have to elaborate? Lust, as has been presented before, is indicated by the presentation of lava flows and volcanic explosions but the main question I had throughout the Total Eclipse section was “How can anyone find the cartoon form of Betty Boop in any way attractive?” I mean her head is wider than her shoulders! Religion gets a very practical nod (apples and serpents, Eves and Adams) but I particularly enjoyed the renditions of Satan. The pristine black and white footage of what presumably were the crowds in Washington during the March for Jobs and Freedom is so stark, clean and vibrant, it leaps off the screen as if it were shot yesterday. On the subject of film restoration, Gelderblom has opted for the dirt and damage of the ages to remain on ninety-five per cent of his shot choices. I think not only is this artistically defensible, it’s significantly cheaper. This undeniably helps.

Where the money was spent, I suspect, was in the absolutely superb quality of the soundtrack, both in the sound design and the original and sourced music. Composer Pieter Straatman’s work is first class and the selection of the well-known classics is measured and these pieces never outstay their welcome. The sound design brings vibrancy to the images in very much the same way that Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old did. Sound, as most experienced filmmakers know, provides and prompts over half the emotional punch of any film and Gelderblom (also the sound editor) does a superb job of buttressing his images with emotive sound design. There was a bed creak I appreciated late on in the film but also a stick whittle on a boat in an early part that I strained to hear but couldn’t. Perhaps it would be more obvious in the 5.1 Surround presentation.

Cinema means many things to many people. To those like Peet Gelderblom, and dare I say myself, its sprockets are our lifeblood, its promise and potential are particularly alliterative; cinema is personal, potent and powerful. Great or small, it transports you and gives you a glimpse of, or a wallow in, another world, sometimes like our own, sometimes far from familiar. In art, cinema is the book’s more flamboyant younger sibling always showing off feeding our imaginations through images in a far more direct way (if not categorically a better or worse one) than a book’s ‘mere’ words do. Books elicit thought and provoke mind’s eye images, with a limitless budget. Written words are achingly personal as the author becomes a close friend for the relatively fleeting period of page turning. Cinema reflects what a book gives you through the prism of another creative mind, a film director, splitting colour and light and throwing it onto a screen to touch and awe us. Cinema is real because what it evokes is real. I was extremely lucky to have started my career as 35mm and 16mm film wound down their own media-market ascendancy. I worked in the cutting rooms for the last six years of celluloid’s dominant life where the smell of recently processed film stock still conjured up an almost overwhelming romanticism for the physical stuff. That tickety-tick sound of a projector is still as emotive as any industrial sound can be. As far as I have been aware, since digital swept film aside in the late 80s and early 90s, computers have no odour. There’s no getting away from the primal stirring that smells are connected to living things... ergo, film is still very much alive.

Devoted people (and Christopher Nolan is certainly one of them) are working to ensure that the future doesn’t spell the end for physical film. In Amsterdam’s Eye Filmmuseum (a beautifully modern piece of architecture where in 2018 I viewed rushes of a film of my own as coincidence would have it) exists a wealth of once loved but now abandoned celluloid; old features, adverts, commercial reels, animation, you name it. The museum opened up its archives to Gelderblom and let his fertile imagination impress upon what he found there, and a form took elemental shape. The filmmaker himself says on the film’s website;

“When Forever Dies is my attempt to take this concept [a chance for orphaned reels of film to find a second home] as far as I can but I never expected the end product to feel so deeply personal.”

He’s not wrong there, Ted. Made from the detritus of scratched colour and black and white film is a work that is compellingly entertaining, at times laugh out-loud funny, arousing, scary and never less than stimulating. As you are watching it you can hear and feel Gelderblom’s world-view whispered into the air dancing between the motes of dust displaced by the projector beam. And it’s one I might share and have it intersect with my own in so many ways. I know I’m a little older than Peet but our explosive cinematic landmarks seem undeniably in sync. It’s probably for this reason that I think I understood the film or at least was in total sympathy with its goals. It’s a fascinating piece of work with the filmmaker’s passion fizzing off the screen and I urge you, if you can, to catch it on a big screen. Here’s the website…

https://www.whenforeverdies.com

|