|

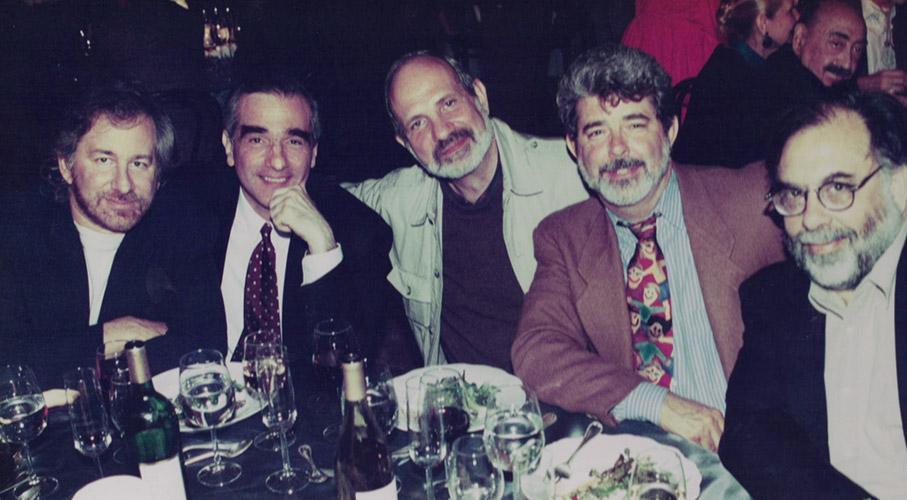

Brian De Palma is a director who seems to have divided critical opinion throughout his career. In Michael Pye and Linda Myles' generation-defining book The Movie Brats: How the Film Generation Took Over Hollywood, I always felt that of the five filmmakers under examination (the others being Francis Coppola, Martin Scorsese, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg), De Palma was the one whose work they liked the least. Others, including celebrated critic Pauline Kael, were more supportive, but De Palma's films have sometimes suffered a critical mauling and public indifference, only to later be the subject of re-evaluation and cult adoration. A perfect case in point is his 1983 remake of Scarface, which took a critical pounding on its release and even landed De Palma a Razzie nomination for Worst Director, but was later the subject of almost obsessive idolisation by gangsta rap stars and Italian mobsters, and is now widely regarded as one of the all-time great American gangster movies. Intermittently, he'd strike gold, as he did with his 1987 The Untouchables, only to take a swan dive into the critical and box-office toilet three years later with his big budget adaptation of Tom Wolfe's seminal Bonfire of the Vanities.

My own engagement with and enjoyment of De Palma's cinema has been a similarly uneven ride. I was of the right age to be knocked for six by Carrie when it hit cinema screens, and through a Movie Brats season at the NFT (now the BFI Southbank), I discovered and was utterly enraptured by Sisters, Obsession and The Phantom of the Paradise, each for very different reasons. It was also through this season that I was introduced to De Palma's more experimental and light-hearted early films, Greetings and Hi, Mom!, both of which featured a youthful Robert De Niro, who was already radiating the sort of talent and charisma that would make him one of the hottest properties in American cinema in the years that followed. But after Carrie, my apprecitaion began to falter a little. The Fury never seemed to quite click for me (I watched it again recently and had the same reaction), and I struggled to engage with what I perceived as the artificiality of Dressed to Kill, although that's a film I am now quite keen to revisit. I did enjoy Blow Out, in spite of some issues I had with the technical aspects of the investigation and the proclaimed greatness of Nancy Allen's parting scream, but fell absolutely head of over heels in love with Scarface on my very first viewing and never understood the critical hostility to it. The turning point for me was probably Body Double, a film that so got up the nose of my closest friend that he wrote a parody of it that we were set to commit to video just for the fun of it, a project that was tragically cut short by my friend's unexpected passing. From this point on I found it hard to easily categorise what defined a Brian De Palma film. Was it the full-blooded magnificence of The Untouchables, or the compelling but altogether subtler smarts of Carlito's Way? And how could it be that the man who made the impressively confrontational Casualties of War would go on to deliver the plodding science fiction opus Mission to Mars?

In recent years, of course, De Palma's whole oeuvre has been subject to fanboy-driven re-evaluation, and that's no bad thing. Revisiting even the films that I once disliked, I've almost always found worthwhile and even exciting things in them. Yet I still can't shake of the conviction that the occasional artificiality of the drama and small but memorable explosions of almost barnstorming excess are being conveniently ignored by some of the director's more ardent devotees. For many, this is all part of the fun of this unique director's bold and distinctive style, and in some ways I'd have to agree with that assessment. But these moments do tend to loudly remind me that I'm watching a film, pulling me out of the story and inviting me instead to marvel at the technical ingenuity of the execution of the sequence or recall the Hitchcock film from which a shot or scene has been borrowed. But given the frankly unreasonable hostility that was directed at some De Palma's work on its release, it seems only fair that we should be encouraged to look the films in a different light. And in these days of shooting scenes with multiple cameras with the aim of crafting a film primarily in the edit, I still get something of a buzz from watching a movie where a whole section of the story can be told in a single, meticulously planned and executed camera shot.

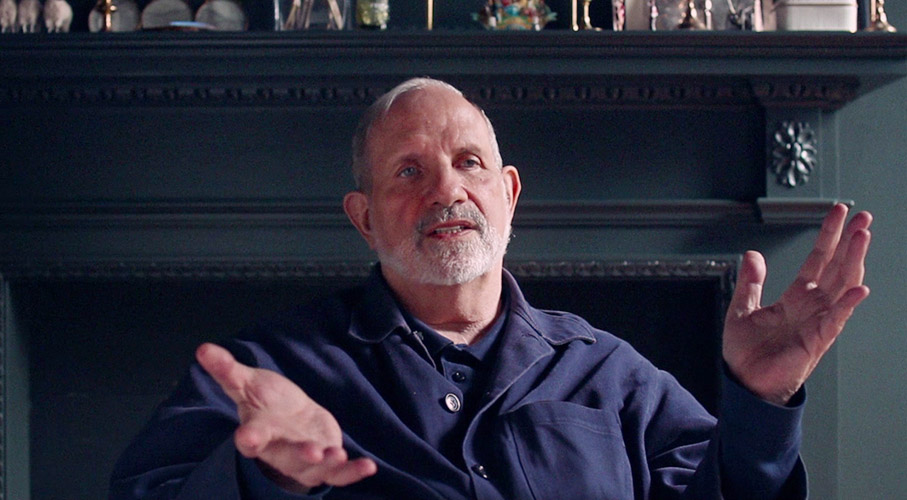

One thing that struck me about halfway through De Palma, a new documentary feature from Frances Ha director Noah Baumbach and The Good Night helmer Jake Paltrow, is that it's actually an unusual choice for a cinema release and a difficult one to critically evaluate. Cinematically, there's really not that much to talk about, since for the most part it consists of a single static shot of De Palma in conversation, which is broken up only by a plentiful supply of film extracts and stills. There's little I can say about the soundtrack either, except to note the slight change in sound quality when the interview switches to clips that were presumably recorded to fill in a number of small narrative gaps, and that a few of the sound edits could have done with an additional beat between them to not make the edits themselves feel quite as obvious. Indeed, should you catch this later when it comes out on Blu-ray and/or DVD, you're likely to experience a small rush of déjà-vu as you watch what may well feel more like a luxuriously extended special feature on a disc for one of De Palma's own films.

But does this matter? Not a jot. The rise of digital projection has made it more cost effective to distribute films that will not have anything close to mainstream appeal, and I'd imagine that this one could still fill a well located specialist cinema with eager film fans for at least a couple of evenings. And while the content may be restricted largely to just one man talking about his career, it's worth remembering that the same could also be said of Errol Morris's The Fog of War, which was critically lauded and won the Oscar for Best Documentary. Sure, Robert McNamara was probably more revealing in Morris's film than De Palma is here, but when it comes to entertainment, De Palma wins it by a beard.

Playing a little like a film version of one of those Faber & Faber books that chart a filmmaker's career entirely through their own words – a filmic De Palma on De Palma if you will – the director takes us chronologically through his film career from his pre-movie days (he was a bit of a science geek) and his early, more experimental work through to his recent features and his decision to abandon the Hollywood system. And it's utterly enthralling from start to finish. De Palma proves to be a great raconteur who gives the impression that he holds no bitter grudges and who frequently laughs at memories that others might still carry as a chip-shaped lump on their shoulder. He's bristling with interesting and sometimes amusing anecdotes about the films and their production – I laughed out loud on more than one occasion – and while some will be familiar to those collecting the more recent disc releases of his films (most of them from Arrow), a fair few are still likely to catch you by surprise (I was unaware, for instance, that he and George Lucas were casting Carrie and Star Wars side-by-side, and that a number of the Carrie actors also auditioned for Lucas's movie). Some of his comments on the success or failure of his own films are certainly memorable, notably when he reflects on the later remakes and alternative versions of Carrie and says with a grin, "It's wonderful to see what happens when somebody takes a piece of material and makes all the mistakes that you avoided." He's also disarmingly open about his personal life and his formative years, which has its share of very real surprises, the most revealing of which saw him secretly following his father when he was cheating on his mother, surreptitiously photographing him and eventually confronting him with a knife. Does any of this ring a cinematic bell?

At a time when documentaries are sometimes sexed up with eye-catching animated graphics and music-driven editing, there really is something to be said for the uncluttered simplicity of the way that this film unfolds. It has a serious advantage over the Blu-ray special features to which I have drawn somewhat spurious comparison by having the budget to include clips of just about every film that even gets a mention, from De Palma's early works to others that merely come up in conversation. Occasionally, these are used to add suggestion to an argument that otherwise remains undeveloped – as De Palma brushes off past accusations of misogyny for the manner in which some of women in his films were killed, Baumbach and Paltrow cut to a shot from Psycho's shower scene, the inference being that he is merely following in the footsteps of others and perhaps even upholding a cinematic tradition. Hmm.

Despite being one of the most structurally unadventurous documentaries I've watched in some while, De Palma is also one of the most entertaining. Its simplicity ultimately works in its favour as it only really asks one thing of its audience, to watch and listen to this man and his stories, and what a pleasurable experience this turns out to be. Ultimately, the only real issue I had with the film is that with a body of work such as this to explore and such an engaging interviewee, I could happily have watched another couple of hours of this – I'm sure there are plenty more stories currently sitting on the electronic cutting room floor. Directors' cut, anyone?

|