|

Every now and then, a film comes along in which the story is kicked off when the leading man comes home to find his wife or girlfriend engaged in sexual activity with an insignificant other. In 1985 it sent Jeff Goldblum on an international adventure in John Landis's Into the Night, and twelve years later set Yakusho Kôji on the road to brutal murder and later redemption in Imamura Shôhei's Unagi [The Eel]. Beating Landis by a year was Brian De Palma and his 1984 erotic thriller Body Double, whose main story begins after struggling actor Jake Scully (Craig Wasson) is given a week's furlough from the low budget vampire movie on which he is working when his claustrophobia causes him to freeze during a take, and he comes home to find his wife going at it like she's training for the sex Olympics.

As always seems to be the way, rather than blowing up at his wife and throwing her out, Scully departs with his dignity between his legs (though it's revealed a short while later that his wife owns the apartment, so in this case the script has that particular plot point covered). In need of a place to stay, he accepts the offer of fellow actor Sam Bouchard (Gregg Henry), who is house-sitting for a friend and needs someone to stand in for him for a few weeks while he takes a gig in Seattle. It's a luxurious place with an overview of the city, and all Scully has to do is make sure that the plants are watered each day. It all seems a little too good to be true, but there's an added bonus in the shape of attractive female neighbour Gloria Revelle (Deborah Shelton), whose nightly erotic display is clearly visible through the lens of the telescope you can't help thinking was installed for this purpose. It's a temptation Scully is unable to resist, but when he takes another peek at her later that night, he sees what looks like a robbery in progress while Gloria is sleeping. When she wakes, a verbal altercation takes place that suggests she and the intruder are known to each other, and concludes with the man slapping Gloria in the face and departing.

OK, let's take a breath here. As anyone who has seen their share of Brian De Palma movies will be fully aware, he has quite a thing for Hitchcock and frequently borrows and reworks sequences and themes from his unofficial mentor. And if you know your Hitchcock movies (and you do, don't you?) then you'll be well aware that Rear Window is a key influence here, and we're only just getting started with that particular borrowing. But there's more. The following night Gloria's back to the erotic dancing, but this time Scully notices that he's not the only one watching from outside. Dressed in workman's clothing, this bad-looking muther is someone you'd run like the wind from if you accidentally spilt his beer. We'll call him the Indian, as that's the moniker he's given in the film because he has the features of a Native American and we're still in the 1980s.

The next day Scully spots the Indian again, and this time he's tailing Gloria into town. Scully gives cautious chase, and when he loses track of his quarry he becomes fixated on following Gloria instead, and Rear Window takes a sharp left turn into Vertigo. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, De Palma takes Scully where the altogether more wholesome James Stewart would be unlikely to tread, spying on Gloria as she tries on a new pair of panties in the poorly positioned changing room of a chic clothing shop, and even pocketing them for himself when she later discards them (quite why she does so is anybody's guess). He then follows Gloria to the beach and at one point positions himself so close to her that he doesn't seem to care if she sees him or not. This all comes to a head when he reveals himself to her and the Indian suddenly appears and snatches her handbag. Scully runs after him, but once they enter a dark underpass his claustrophobia kicks in and the Indian gets away with whatever it was he was looking for.

To talk about what happens next will take us into spoiler territory, but it's also the kicking off point for the investigation of the mystery that sits at the film's core, one that involves the introduction of an important new character. It's also where the most contentious scenes sit, and it's nigh-on impossible to critically engage with the film without discussing them. So in the spirit of not ruining things for first-timers, if you've not seen the film and have every intention of doing so then you might want to skip ahead to the technical specs when I sound the final warning bell below. I'm not going to give away the ending, but am going to reveal at least one major plot twist, albeit one that those who know their Hitchcock influences might just see coming.

But before I get to that, I feel the need to make a confession. I first saw Body Double on its initial cinema release and was not a fan. OK, that's probably a small understatement. I hated it. My creative viewing companion of the time loathed it so much that he spent the next few weeks writing a mocking parody of it that if we'd had the sort of easy access to quality cameras and editing equipment that we have now, we would have doubtless have filmed and thrown up on YouTube, where De Palma fans everywhere would be free to curse us for the judgemental twerps that we doubtless were. Then again, we weren't the only ones with bugs up our arses about this particular movie, which took an absolute critical caning on its release and was widely reviled for is misogyny, its blatant Hitchcock borrowings and its cinematic excess. The cult following that has elevated De Palma to the point where an interview with him can form the basis of a feature film of its own is one I have not yet been swallowed up by, and revisiting the De Palma films that irked me in my youth, I've found they still irk me for the same reasons today. But soundly countering this are substantial elements in all of these film that made little impression on me back in my younger days but impressed the hell out of me all these years later.

And so it also proved to be with Body Double. Having been gently encouraged to give it a look by someone whose views I respect, I apprehensively agreed to take the review disc and give it a spin. My first viewing of it was late at night immediately after coming out of hospital following an operation on my foot that required me to lie down and keep the damned thing elevated. I put this film on (confession #2) because I expected to find it easy to turn off once I was tired enough to sleep. Instead I ended not going to bed until almost 2am. Against all expectations, this time around I was soundly hooked from an early stage.

There's a lot De Palma gets so right in the film's first half-hour that I began to seriously wonder what my earlier problem with it was. What really impressed was how much time he devotes to setting up the main characters and the story, giving us plenty of time to get to know Scully and engage with him as a character before the mystery really starts to unfold. De Palma also builds the foundations for film's biggest twist here (which I won't be revealing), and re-watching it again a couple of days later I was struck by how effectively he covers his tracks – I didn't feel like kicking myself for missing something, nor cheated because essential clues were kept from me. That the horror flick that Scully is working on at the start is the sort of low budget vampire movie that only really exists in the mind of directors who've never really watched a low-budget vampire movie is something I'll let slide.

My first pang of flashback apprehension occurred when Scully took his first look at Gloria doing her nightly erotic display. It's not the display itself that's an issue – it's a plot point, after all – but the length of time this sequence goes on for, far longer than is required to establish that Scully is both intrigued and a just little uncertain about the moral implications of what he is doing. Whether running this in real time is designed to prompt us to question our role as potential voyeurs when we sit down to watch a movie (it does have that effect), or is the result De Palma's fondness for photographing beautiful women (he said it, not me), is up for discussion. It's probably not helped by the musical theme that accompanies these furtive telescopic encounters, one whose tinkling electronic erotica has just a whiff of soft-core porn.

But no matter. In spite of the fact that Scully would make the world's worst private detective – at least when it comes to secretively tailing a subject – his stalking of Gloria, punctuated as it is by unpredictable appearances by the Indian and a claustrophobic episode in a packed scenic elevator, proves strangely addictive, in spite of the sheer length of the sequence as a whole. It comes to a head with Scully's claustrophobic episode in the dark underpass, which is superbly realised through a combination of inventive camera trickery, Pino Donnagio's panic music and actor Craig Wasson's convincing physical distress. Yet just a couple of minutes later, all this good work is colourfully undone when Scully and Gloria kiss in a sequence that still has me slapping my forehead in disbelief. As they engage in the sort of completely artificial kissy-feely dance that people only do in movies, they are rotated on a turntable against a matted-on backdrop, while Donnagio's score goes into romantic overdrive, as comically artificial a representation of romantic passion as I've seen, at least in the context of a serious drama. I was waiting for a Billy Liar moment to reveal that the whole thing had been created in Scully's delusional head, yet while it does calm down as the kiss comes to a close, we're left to assume that it actually happened, which means that Gloria's reaction to being suddenly kissed by a stranger who's been stalking her all morning (albeit one who chased down a mugger and retrieved her handbag) is to unquestionably accept his advances and kiss him back. Wow. Intriguingly, in the extra features on this very disc, De Palma openly admits that this sequence was a mistake, one that made audiences laugh and pulled them temporarily out of the film.

But the scene that caused the most controversy is yet to come, and it's here that I'm walking into spoiler territory and thus now that newcomers would do best to bail. See you at the tech specs.

OK. The scene in question takes place the following night when Scully is spying on Gloria again and spots the Indian inside her house clearing out her safe. Yep, we're back in Rear Window territory, this time by way of John Carpenter's own borrowing from the same in his 1977 TV movie Someone's Watching Me. Scully's attempt to warn Gloria by calling her by phone not only comes too late, but appears to help seal her fate when the Indian strangles her with the telephone cord. She manages to break free, so her assailant attacks her instead with an electric drill, one with the biggest and longest drill bit you're likely to have ever seen. Even today, having had a couple of decades to prepare myself for re-watching this sequence, it still struck me as over-the-top to an absurd degree. De Palma's justification for this choice of weapon was that he needed something that could bore through both Gloria's body and the floor below and allow blood to run through the ceiling for hapless Scully to witness. Fine, but what about story logic? The Indian had easy access to the house via the key card that he stole and appears to have known the combination of the safe, so exactly why is he carrying this unwieldy and functionally pointless power tool? You could probably argue that he always intended to kill Gloria in a messy and spectacular manner (later events give this a small degree of credence), but since his first move is to try and strangle her with the telephone cord, that doesn't really wash. In an interview in the booklet included with this disc, De Palma claims that the Indian brought the drill with him to crack the safe, but unless its walls were about three feet thick and made of wood, that cuts no ice either. This is also one of those kills that unfolds slowly enough to make you wonder what the Indian is waiting for as he leeringly advances on Gloria at the speed of a sedated tortoise (yeah, I know, this is De Palma setting up the power cord gag that will soon follow), while Gloria stands motionless before him being all female and frightened. Can De Palma really have been all that surprised when people read this in Freudian terms, presented as we are with the sight of a hulking alpha male advancing on a helpless woman with a huge rotating phallus, which he then uses to bloodily penetrate her, an action framed at one point to position the descending dill bit between his legs? This really is a case of the tail wagging the dog, and for a few crucial minutes transforms this Hitchcockian thriller into a sensationalist giallo, where murder is all about the spectacle of the kill, despite the fact that we don't actually witness the graphic details.

I'm guessing it was this scene and that whirly kissing sequence that helped taint my first viewing back in the mid-80s, and they continue to function as eye-widening disruptions to an otherwise largely arresting narrative. That said, the film's second half, where Scully teams up with porn star Holly Body (a bold breakthrough role for a defiantly unembarrassed Melanie Griffith), also delivers a couple of minor niggles. Transforming the shooting of a porn movie into a pop video for Relax by Frankie Goes to Hollywood is a peculiar but lively interlude in itself, but this particular porno feels about as grounded in the real world as the low budget vampire flick in the opening scene, while the sequence in which Scully calls investigating Detective Jim McLean to explain what's been happening feels as clunky a piece of catch-up exposition as that tagged-on psychiatric babble at the end of Psycho (that said, this is very much Scully's interpretation of events and De Palma is clearly using it to re-enforce his biggest plot deception). And while I rather liked Big Jim McLean, who has damned good reason to believe Scully is a bit of a perv, the patrol cop who tries to stop Scully at the climax is a dumb as a post, completely ignoring Scully's warning that an assault is taking place just a few yards away and trying to arrest him instead for being a pest, then failing to give chase or alert any of his nearby colleagues when Scully thumps him and runs away. Maybe he was only two days from retirement.

If I seem to be laying into Body Double a bit, then it's probably because the things that still bugged me after all this time really still bugged me. But countering and ultimately conquering this is my happy discovery that there's way more to enjoy and admire here than I ever remember there being. The mystery at the film's core is ingeniously constructed and unfolds compellingly, Scully's debilitating claustrophobia is put to effective narrative use (the finale is particularly neat on this score), the performances are solid and many of the key scenes are captivatingly directed. The jury's likely to be out for a good many years on whether the film indulges in and celebrates male voyeurism and sexualisation of women, is an exploration and sly critique of a film audience's role as complicit voyeur, or is, as De Palma claims, really all about learning to not trust anything we see on the screen. Take your pick. One thing's for sure, it's every inch a Brian De Palma film, and despite its nutball moments (or, if the mood takes you, because of them), Body Double is a smartly devised and well-crafted thriller that I'm rather glad I took the time to revisit.

The 1.85:1 transfer here was sourced from a 4K restoration by Sony and looks pretty damned fine. There's a strong level of detail that particularly shines on the daylight exteriors, which is also where the well-balanced contrast and naturalistic colour are at their finest. Black levels are unwaveringly solid, but not in a manner that is detrimental to picture detail (don't trust the screen grabs here), even in the film's many (and carefully lit) night scenes. A fine and un-enhanced film grain is visible throughout, there's little to no trace of any damage or dirt and the image sits rock solidly within frame. Nice one.

You can choose between the original Linear PCM 2.0 stereo soundtrack or a DTS-HD 5.1 surround remix; both are in fine shape, but the music really gets an extra kick on the 5.1 track, with the pounding bass on Relax the most obvious benefactor. The difference in volume between the dialogue and the louder blasts of music is sometimes substantial on both tracks, so be cautious with that volume control if you want to keep your ears and your windows healthy.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have also been included.

Craig Wasson Interview (7:26)

An archive interview with lead actor Craig Wasson from what looks like one of those American daytime shows in which chats with celebs are conducted on a set that's been made up to be the female host's living room. We don't learn a lot here, though our host claims she's never seen Brian De Palma smile, which surprises Wasson, who describes him as the best director he's ever worked with. She also predicts that Body Double will make Wasson a household name. Erm...

Pure Cinema (38:16)

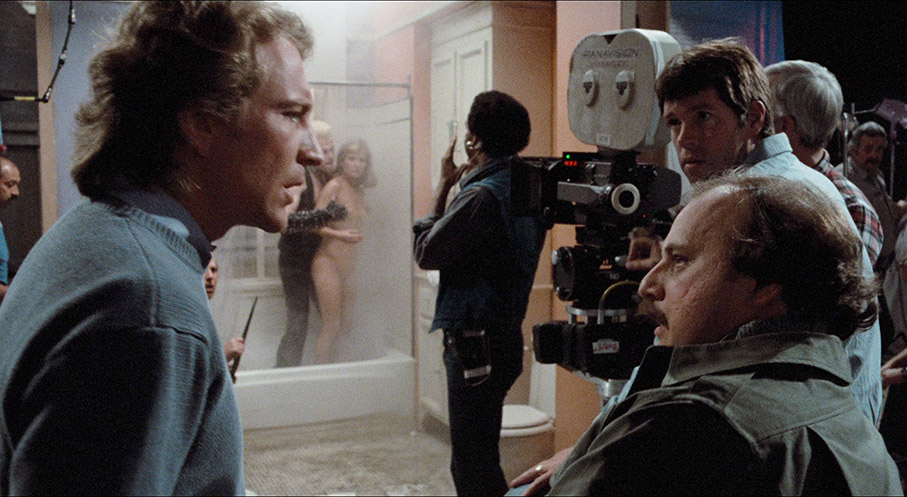

An interview with Joe Napolitano, who was De Palma's first assistant director on Blow Out, Scarface and, of course, Body Double. There's quite a bit of praise for the film and its director, but also some useful behind-the-scenes details, including info on the locations (a couple of which are shown as they are now – the beach hotel is depressingly decrepit), shooting the porno scenes, how they controlled the sunlight when filming the mall scene (this is really interesting) and the technical problems they faced on the aqueduct climax. This was produced by regular disc extra favourites Fiction Factory.

The next four extras are actually separate chapters of a single documentary on the film and its making, and include interviews with De Palma and actors Melanie Griffith, Grey Henry, Deborah Shelton and Dennis Franz.

The Seduction (16:43) looks at how the film went into production, and De Palma reveals that he originally cast an actual porn star in the Holly Body role but the head of Columbia Pictures apparently went ballistic at the prospect. Griffiths outlines how she became friends with De Palma through her then husband Steven Bauer (who co-starred in Scarface) and how she pushed for the Holly Body role. Shelton recalls her audition consisting of scenes from Body Heat and Scenes From a Marriage. Henry discusses a plot point you shouldn't know about before you see the film for the first time, and Dennis Franz reveals that he agreed to play the director of the in-film vampire movie if he could play him as De Palma – De Palma even leant him his own jacket for the role.

In The Setup (16:54) De Palma talks about telling stories in purely visual terms, while Shelton reveals that he was very precise about the women's costumes, their materials and even the nail varnish used. It's here that De Palma expresses his satisfaction with the visual representation of Scully's claustrophobia and admits that the rotating kissing scene doesn't really work and was a mistake on his part. I was intrigued to learn that the dog that attacks Scully in Gloria's house was the one from Sam Fuller's White Dog – actually there were three visually identical canines of varying degrees of viciousness, and the angriest one was apparently something to be feared. The suggestion is that this is the one that they set on Wasson.

In The Mystery (12:15) De Palma talks about the process of making the in-film porn movies and trailers and the porn pop video, and Griffith outlines her determination to play Holly as smart and not in any way dirty or nasty. We get some more info on the filming of the finale, and De Palma explains why the original opening sequence was moved to the end credits.

The Controversy (5:31) looks at the negative reaction to the film on its release, which effectively gets brushed aside as political correctness, while De Palma counters accusations of misogyny by explaining how much he likes women, including how much he likes photographing them. To be fair, everything I've read and all the interviews I've watched suggest he has a strong rapport with the women he works with, but none of this really addresses the charges made against the film itself.

Theatrical Trailer (1:29)

Presented as an artistic soft-core porn piece in which the camera trails over a naked female body in soft focus close-up, before a final sting that is suggestive of violence without actually showing it.

The Isolated Score focuses exclusively on Pino Donnagio's music for the film in Linear PCM 2.0 stereo – no Frankie Goes to Hollywood here. The sound quality is very good.

Image Gallery

70 production and behind-the-scenes stills and one poster, which are manually advanced.

Booklet

Another fine booklet from the good people at Indicator, this one kicks off with a new essay on the film by Ashley Clark that thoughtfully deconstructs its Hitchcock borrowings and makes a solid case for it as a work in which the viewer should not trust anything they see. This is followed by an interview with Brian De Palma from the September/October 1984 issue of Film Comment in which he is questioned directly about the film, the nature of and influence of cinematic violence and pornography, and more, to which he gives some interesting responses. This is followed by Brian De Palma's Guilty Pleasures, a reprint of an article from the May 1987 edition of Film Comment in which De Palma selects some of his favourite and sometimes unsung films and elaborates on why they are special to him. There's some terrific stuff here, including Sam Fuller's White Dog, William Castle's Homicidal, Mike Hodges' Get Carter and (this one caught me out) the Maysles brothers' ground-breaking documentary Salesman. Finishing things off is a reprint of Richard Combs' negative review of the film from the May 1985 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin. Credits, very brief info on the restoration and a number of production still have also been included.

As you've probably gathered, I still have a few issues with Body Double, but coming back to it after years of it being on my dislike list, I was surprised and a little delighted by just how well so much of it plays and how much I enjoyed it. As a thriller it's ingenious and smartly constructed, and while it's Hitchcock borrowings and occasional excesses do tend to occasionally break the spell and remind you that you're watching a movie construct, it's surprisingly easy to drop back in and get caught up in the story again. The HD transfer on Indicator's Blu-ray is a strong one, and the special features – particularly the excellent booklet – are all well chosen (the Craig Wasson interview may not amount to much, but since he doesn't take part in the documentary it's nice to have something). The film still won't be for everyone, but against my expectations I find myself having to warmly recommend this disc.

|