|

Rock and pop musicals are precarious beasts, something especially true of those featuring a popular group or musical artist of the day. Such fame can be fleeting, and a couple of decades later the appeal of such films can be lost in time, re-branding them as curios and musical barometers of a bygone time. It's perhaps no surprise that the most celebrated rock musicals had a life before they became committed to film – The Rocky Horror Picture Show was already a cult stage success, and both Tommy and Quadrophenia were hugely popular concept rock albums.

Any attempt to create a film rock musical from scratch takes some balls and asks a lot of the composer, who is required to produce an album's worth of songs and make them both relative to the story and strong enough to score as stand-alone set-pieces. Such was the case with Phantom of the Paradise, a too little seen film from 1974 that was directed by Brian De Palma. Excuse me? Brian De Palma? The man who two years later would strike commercial gold with Carrie* and whose name is more readily associated with visually stylish thrillers and big budget crime dramas like Scarface and The Untouchables? The very same. The project seems all the more surprising when you consider that it was sandwiched between the Hitchcockian double of Sisters and Obsession. And one thing you would definitely not call Phantom of the Paradise is Hitchcockian.

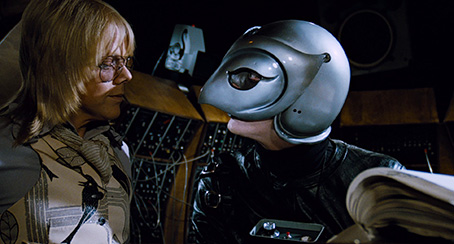

As the title suggests, the key inspiration here is Gaston Leroux's celebrated novel The Phantom of the Opera and the film adaptations of it. Struggling young composer Winslow Leach is working on a rock opera version of Faust when he comes to the attention of a hugely successful but Machiavellian music impresario known as Swan, who believes this is the perfect music to open his new rock palace known as The Paradise. But instead of hiring Winslow, Swan steals his composition and has him beaten up and thrown in jail on a trumped-up charge of drug possession. Furious at the news that Sawn has scored yet another hit with his stolen music, Winslow escapes, but in the course of a rampage through Swan's company headquarters, an accident with a record press leaves him facially deformed. As the opening night approaches, the masked and costumed Winslow stalks the corridors of The Paradise, hell bent on sabotage and determined that only the beautiful and angelically voiced Phoenix, with whom he has become entranced, should ever sing his music.

For the record I'm just giving you the essentials and there's a good deal more plot than I've outlined here. As both writer and director, De Palma moves his narrative forward at a dizzying lick, fuelled by a fantasy-reality visual style and a storytelling economy that dispenses with the need for real world logic without ever feeling absurd. Thus Winslow's escape from jail consists of nothing more than him diving into a box (in plain view of everyone), from which he explodes moments later when it tumbles from a delivery van onto a city street. Stop to think about it and it makes no sense, but in the film it works a treat and occupies a mere ten breathless seconds of screen time.

This supercharged approach to story development is perfectly complimented by William Finley's energised performance as the hapless and tormented Winslow Leach. Finley was one of those criminally underused character actors who you just know would have been in constant demand if the right high profile role had just come his way. In a career spanning 44 years (he sadly died in 2012), he only appeared in a paltry twenty-one films, several of them for De Palma** (the two met at Columbia University), including a splendidly creepy turn as Margot Kidder's protective ex-husband in Sisters, which is also set for a future Arrow release. Here he gets to play his only lead feature role and works small wonders with it, engaging us from the off with his passion and worldly innocence and, as stated by Paul Williams in the extras on this disc, able to do more with one eye when encased in the Phantom's mask than a good many others can do with their whole face and body.

Ah yes, Paul Williams. I'll confess that when I first saw Phantom of the Paradise back in the late 1970s I had no idea who Paul Williams was, despite his considerable fame within the music business. This was perhaps indicative of a common youthful romance with the performers of pop music rather than those who write or produce the songs, though I was never a fan of the higher profile acts that he most famously wrote for. I remember back then thinking that he was an oddball choice for Swan, his diminutive stature, cherubic looks, David Cassidy hairstyle and peculiar cod-English accent (bad guys had to be English in American movies even back in the 70s) making him about as hard a sell as you can imagine as the all powerful and amoral monster that Swan is supposed to be. I had the same reaction when I watched the film again all these years later. At least I did at first. You see, once you get past the initial "You mean, that's Swan?" surprise, this contrary casting actually proves rather effective, his almost child-like sweetness lending his cruel double-dealing and self-satisfied amusement at Winslow's misfortune a particularly nasty edge. As an actor he's outclassed by Finley at every turn, but he still has his moments, notably in a rare but utterly convincing look of troubled regret while watching a tape of his own recent misdeeds, and in a climactic bathtub flashback that provides an explanation for his meteoric success and stubbornly youthful looks.

Completing the trio of leads is the then impossibly young-looking Jessica Harper, a strikingly pretty actress whose wide-eyed schoolgirl looks and subtle undertow of bubbling sensuality would surely have set her up for superstar status had she been born and raised in the silent era. I first saw Harper in John Byrum's 1974 Inserts, a rarely seen and seriously undervalued tale of a once great silent filmmaker reduced to making porno flicks (check it out if you can find it – the cast alone is worth the price of admission), and shortly after in Dario Argento's visually and aurally astonishing 1977 horror opera Suspiria, where her way with facial innocence is exploited to the full. Hearing her sing for the first time here can be something of a shock, one triggered by the disbelief that so powerful a voice could emerge from so seemingly delicate a frame. It's in the performance of her audition song that her musical talent is showcased most effectively, as she commands the stage with her singing, her body language and her fiery sexuality in a manner that still makes me go a little weak at the knees.

Which rather neatly brings me to Paul Williams' score of songs for the film. In the months and even years that followed that first London viewing I had fond recollections of the film and of Finley in particular, but had it in my head that the songs were a bit cheesy and not all that good. Coming back to the film later I've been given cause to revise that viewpoint. The songs are good, and I mean really good, a solid collection of consistently well written and passionately performed numbers that are also key to the film's dark satirical sense of fun, parodying everything from greaser rock 'n' roll to Beach Boys surfing tunes with wit and considerable musical aplomb. What they're not, at least for me, is stick-in-the-brain memorable – I've re-watched the film three times in the past couple of weeks and still couldn't hum a single one of them or recall their lyrics. This does mean that every time I watch the film I'm actually surprised by how good the music numbers are – why they don't seem to stay with me is anybody's guess, but I wouldn't change a note, so effectively is the score weaved into the fabric of the film.

Although it plays cheerful games with its source material, in other ways Phantom is more faithful to Leroux than you might expect, including the role played in the story of a musical version of Faust, which here escapes Winslow's song sheet and is weaved into the story. By agreeing to work with Swan, Winslow makes that fabled deal with the devil and leaves himself open to exploitation and ruin, while the art in which he invests his heart and soul is transformed by corporate greed into yet another commodity to be sold to an audience pre-programmed to throw money at whatever they are told is the Next Big Thing. Swan is the very epitome of amoral capitalism, getting rich on the efforts of others whom he then casts aside, and whose role in the creative process is limited to tweaking the damaged Winslow's electronic voice ("Perfect" he remarks with clear satisfaction when he has it sounding like his own) and to pump him with amphetamines when he is close to collapse.

That the story is not destined to end well for anyone is signposted some time before the surprisingly moving finale (full marks again to Finley, who really does commit here). But the journey there is peppered with amusing encounters and references, from Swan's response to being first confronted by The Phantom (he reacts not with shock but an amused and almost friendly, "Why Winslow, good to see you. Been looking for you everywhere") to the split-screen bombing that parodies the famous opening shot from Touch of Evil. The humour we're encouraged to draw from the camped-up delivery of monster rocker Beef may date the film to a less progressive time, but the role is still performed with infectious enthusiasm by Gerrit Graham, and he absolutely shines in a sequence that initially apes the shower scene from Psycho, only to take an unexpected and hilarious turn, its comic effectiveness down almost solely to Graham's eyeball acting and a perfectly timed yelp.

There's been some debate about whether the makeup worn by Beef's backing group The Undead was purloined from the recently formed Kiss or was purely coincidental. Kiss has claimed the former – well they would, wouldn't they? – but it's worth noting that Beef's stage show has just a whiff of the rock-horror theatrics of the by then well established Alice Cooper, who was also rather famous for his facial make-up and is even name-checked on the cards at the Death Records reception desk. And seriously, does it matter? It's just one more ingredient in a consistently enjoyable blend of inventively referenced material and imaginative thinking on the part of De Palma and his talented collaborators. They even get the jump on Ken Russell through cinematographer Larry Pizer's lively and expressionistic use of ultra-wide-angle lenses, which pre-dates Dick Bush's equally stylised use of the same on Tommy by a good two years.

When I heard of this re-release and started reading the fan comments, I did wonder whether a key reason that the film has achieved cult status was its lack of widespread fame and initial box office success (that it ended up screening as a supporting feature to The Rocky Horror Picture Show particularly irked its admirers – personally that sounds like a mother of a double bill), and I've not always shared the unbridled enthusiasm that has seen some of De Palma's 80s thrillers championed as previously misjudged masterpieces. But revisiting Phantom of the Paradise after a gap of so many years has proved a thoroughly pleasurable experience in every respect, and I'd actually suggest the film is even better than I remember.

OK, the contrast is a bit on the aggressive side at times, delivering inky blacks but at the expense of some of the shadow detail, but in every other respect this is a splendid transfer, with strong picture detail and vibrant colour, which really brings the film's almost comic-book fantasy palette to life. As you would hope of such a restoration, there's not a dust spot to be seen, and no trace of any damage. Pleasingly the framing is the original 1.85:1, not the 1.78:1 crop that's becoming so popular for Blu-ray transfers of older films.

There are two soundtracks on offer, Linear PCM 2.0 stereo and DTS-HD Master Audio 4.0 surround. There's not a huge difference between them, but the 4.0 track definitely feels fuller and livelier, while the PCM seems to have a slightly brighter treble response. Clarity and dynamic range are good, but both take a considerable jump during the music numbers, which leap from the speakers and really do sound superb, particularly impressive for a forty-year-old low-budget feature.

Actually, there is also an isolated music and effects track, which is also Linear PCM 2.0 stereo. As a musical, this film does at least justify the inclusion of this sometimes bemusing feature.

Optional English SDH subtitles are also available.

Paradise Regained (50:13)

Made in 2006 for a French DVD release (which explains why Gerrit Graham intermittently breaks into the French language), this is a comprehensive look back at the making of the film, built around interviews with key participants. Contributors include writer-director De Palma, composer and actor Paul Williams, producer Edward Pressman, cinematographer Larry Pizer, editor Paul Hirsch and actors Jessica Harper, Gerrit Graham and (hoorah!) William Finley. There are plenty of entertaining and revealing stories here, including details of the four law suits that were hurled at the film just as 20th Century-Fox was preparing to give it a sizeable release, and I particularly liked the tale of the feathered bikini bottoms that the religious dancing girls refused to wear because they looked like pubic hair.

Guillermo del Toro Interviews Paul Williams (72:22)

The affable Paul Wiiliams is interviewed by his friend and Phantom devotee Guillermo del Toro, whose enthusiasm, as ever, is impossibly infectious. Their friendship dissolves that cautionary barrier between interviewer and subject, allowing for a chat that is both enthralling and surprisingly frank – Williams is open about his wandering weight and health during a period in which he was, by his own admission, "a major addict." As a fan of Williams' music as well as his performance in the film, del Toro's questions and observations are as intriguing as Williams' responses, and Williams pays impressive tribute to leading man Finley's talent when he says of the scene in which the horrified Winslow watches Swan and Phoenix cavorting on Swan's bed: "Bill Finley does more with one eye behind that mask than I could have done with six of Paul Williams' talents." Great stuff.

The Swan Song Fiasco (11:25)

A fascinating featurette that details the changes that De Palma was required to make when his choice of record label name – Swan Song Records – turned out to be the very one selected by Led Zeppelin for their own record label. The Zeppelin lawyers sued and the filmmakers were forced to remove all trace of the name from the by then completed film, which involved trimming some shots and employing time consuming and sometimes wobbly process work to hide it. Nowadays, of course, this would be far less of an issue, as painting out or replacing unwanted elements can be done by almost anyone with a laptop computer and the right bit of software.

Archive Interview with Rosanna Norton (9:38)

Shot about ten years ago on a low-band hand-held camcorder with the date stamp switched on (why did people do this?), the film's costume designer talks directly to the camera about her work on the film, with particular focus on the costumes for The Phantom and Beef. Interesting to learn that due to the film's low budget she did much of her shopping for costumes at thrift stores (that's charity shops to us Brits).

William Finley on the Phantom Doll (0:35)

The wonderful William Finley does a quick sales pitch for a Phantom action figure, which probably changes hands for hundreds of dollars now.

Paradise Lost and Found (13:39)

A collection of deleted shots, alternate takes and bloopers. None are accompanied by the location sound and so are instead scored with music, except where side-by-side comparisons are made with the finished film. There are a LOT of takes of The Phantom's triumphant reaction to his attack on Beef.

Original Trailers (3:28)

Two different but equally serious-voiced trailers with their share of spoilers, especially the second one.

Radio Spots (2:28)

4 radio spots, three of which are voiced by cult DJ Wolfman Jack!

Gallery

A collection of 31 monochrome stills, including a couple of publicity photos and some behind-the-scenes shots by Randy Black.

A cult rock musical that justifies that label and one that really does deserve to find a wider audience, even all these years after it should have been a hit. Had it found the success it deserved, I can't help wondering what direction De Palma's career might have subsequently taken and what other unexpected projects might have come his way. It's also the late, great William Finley's very finest film hour (well, hour-and-a-half), and what the hell, it may also be Paul Williams' too. Arrow have once again picked a goodie and done full justice to it with a generally strong transfer and a splendid collection of extras. Enthusiastically recommended.

* Sissy Spacek, who went on to play the titular Carrie in De Palma's breakthrough hit, was a set dresser on Phantom, while her husband Jack Fisk was the film's production designer. If this wasn't enough to lend the pair a small cult status, they also worked on David Lynch's Eraserhead.

** A fan favourite Finley role was his memorable guest spot as magician flamboyant Marco the Magnificent in Tobe Hooper’s underrated 1981 The Funhouse.

|