"Who

the hell cared about Rwanda?" |

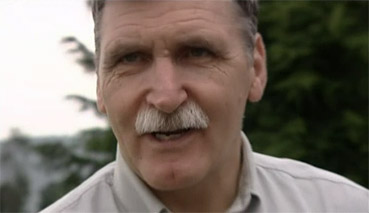

Lt. Gen. Roméo Dallaire |

|

"It's

the U.N." |

A Rwanda based U.N. worker giving an

excuse for bureaucratic incompetence. |

Ten

years ago, while the world's media centred on the fate of

a single black man in California, no one heard – or indeed

wanted to hear – the hundreds of thousands of screams coming

from the middle of Africa... What price human life?

In

Rwanda, central Africa, in 1994, while the world was hypnotically

distracted by the O.J. Simpson circus (sorry, trial), an

African government-backed militia and extremist factions

exterminated 800,000 human beings in one of the worst atrocities

of the late 20th century. Over a period of three months,

the Hutu soldiers and citizens of Rwanda shot and mostly

hacked to death their Tutsi brethren and Hutu moderates

in one of the most appalling acts of mass murder the world

has ever witnessed (or in this case, one which the world

had pointedly avoided witnessing). I have outlined the historical,

political and sociological aspects of the massacre in my

review for Hotel

Rwanda and won't dwell on them in this piece

except perhaps to underline one historical facet of this

awful event.

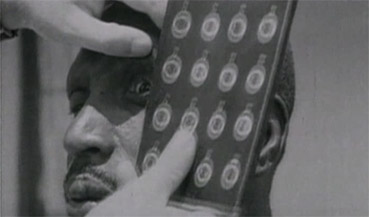

White

colonials (in this case Belgian) essentially divided the

population of Rwanda according to a series of physical attributes

that were measured with instruments that seem to have been

left over from Hitler's eugenic programme. In the fifties,

a nation was divided by bad science employed by an arrogant,

self-appointed white supremacy and kick-started an already

tribal based culture on the road to genocide. I mentioned

in Hotel Rwanda that it was not 'our fault'

but historically it seems I was mistaken. It feels simply

wrong to hear these native Africans speaking in perfect,

one assumes, Belgian French. Their colonial chains had become,

over successive generations, their unnaturally selected

method of verbal communication.

Hotel

Rwanda is a dramatic reconstruction of one hotelier's

brave attempts to save as many lives as possible during

the terrible carnage. Its perfect DVD companion, Shake

Hands With The Devil, is a character study, an

unflinching look at a man who played a central role in attempting

to arrest the unfolding atrocities (in Hotel Rwanda,

it's Nick Nolte's character who plays an interpretation

of Lieutenant General Roméo Dallaire). Dallaire cried

out for help and the world simply ignored him. He now lives

with the terrible burden of guilt (he's a staunch Roman

Catholic which cannot ease that particular burden) believing

that if he had done his job differently, lives would have

been saved. The overwhelming feeling after seeing the movie

is that Dallaire is the only one with this horrifying delusion,

one which led him to a park bench in Canada, having numbed

the grief with a great deal of alcohol culminating in several

post-traumatic stress syndrome driven suicide attempts.

It is this documentary's triumph that Dallaire's story is

presented with passion and heartbreaking depth. Not for

nothing did Robert Redford say that Shake Hands

With The Devil was a film his Sundance festival

was created for. Bravo Bob.

Imagine,

if you will, the United Nations. Yes, that emasculated organisation

that refused to give Bush and Blair an easy politically

sanctioned way out while they plotted to invade Iraq. Its

principal function (logically speaking) is to monitor the

world and assist in situations that require peace-keeping

forces. Rwanda was a powder keg and the fuse had been lit.

Dallaire's mission was to put the fuse out. He was given

a handkerchief and ordered to cover a football field. To

the man's credit, he really tried. But the world didn't

want to help. The world didn't want to know. Who cared about

Africa? Dallaire was to enforce the peace in a situation

that was clearly going to blow up in his face. He had so

little support from the United Nations that one wonders

why he was sent out there in the first place. Just because

he spoke French? If it was a token gesture then it was lost

on a beautiful country ripped apart by civil war and one

about to be hacked apart splattering the history books with

the blood of innocents.

The quintessential core of this fine documentary is the

character of Roméo Dallaire. We are invited to see

this appalling tragedy through his eyes and his eyes alone.

He had written a book because he did not want something

like this to ever happen again (who would?) and to exorcise

a few particularly horrific personal demons. He wanted the

world to know that international apathy costs more than

political leverage. Be warned. The snatched footage of machete

murder and the butchered bodies floating garishly in the

rivers of Rwanda take a strong stomach to handle. I doubt

if the film-makers wavered for a second in the decision

to include this footage (the director's commentary tells

us otherwise but these images are vital in grasping the

leaf of the blood soaked rainforest). You really do have

to see it front and centre because it is – by its scale

– almost impossible to believe.

The

director Peter Raymont (or editor, Michèle Hozer

– impossible to know whose creative decisions prevailed)

has peppered the film with visuals that act as tug boats

to the story. Sometimes they are a little too contrived

(nodding to and playfully linking to Dallaire's own voiceover)

and make you think of the film-makers' choices rather than

their subject; "the fog of war..." line on the

soundtrack cutting to a real ground fog in the Rwandan archive

footage. This is a small gripe as I have been as guilty

and more as a director and editor myself. Sometimes there

is simply not enough footage and you have to get creative.

The film follows Dallaire back to Rwanda with his wife (cheaper

than his psychiatrist as the director's commentary tells

us) ten years after the genocide reliving his story as he

revisits significant locations and meets significant people,

survivors of a bloodbath.

The

film opens and closes with Samuel Barber's Adagio for Strings

on the soundtrack. Those of you who either know (a) your

music or (b) your Vietnam movies will recognise this sublimely

haunting track as Oliver Stone's choix de jour for Platoon.

I'm not suggesting that the music has been overused (well,

yes, I am) but the justification is that it was played as

Dallaire wrote his book and one can't argue with that –

well, one can but it's such an amazingly haunting piece

that it's justified here in spades despite its now apparent

ubiquity. Without using a lot of poor quality library material,

director Peter Raymont had to trust his story and stay focussed

on Dallaire and the film is stronger for that decision.

Why?

Because

Dallaire is the perfect soldier. I say this with no personal

first hand knowledge of the man or his methods. It's simply

because if Dallaire is half the man as presented in this

documentary, then you would want him commanding you in war.

He never forgets or sidelines his humanity – his best asset.

He is visibly moved by situations and people. He is stunned

that the political world, specifically the U.N., can casually

dismiss Africans as sub-human (the subtext in all of his

contact with them). President Clinton, after the event,

apologised for not knowing what would happen and interview

subject U.N. Envoy Stephen Lewis airily dismisses this as

the lie he believed it to be. In a tense and fraught situation

(Dallaire's HQ is being attacked), the General plays music,

an absurd pro U.N. rock anthem, which makes all of his soldiers

smile despite themselves and their awful predicament. His

is a leadership with a capital 'L'.

In trying to find ways to express himself, Dallaire falls

back on religious terminology (he is a religious man after

all), a convenient and unfortunately straitjacketed way

of processing his experience. Dallaire is staunchly moral

and in his job (enforcing his masters' and his own moral

code on to others) he has to believe what he is doing is

in all ways 'right'. One cannot argue with the idea of 'peace

keepers'. To invoke 'evil' and 'the devil' as a way to understand

what happened in Rwanda is a little too narrow for me. As

critic Geoff Pevere said on the second commentary, these

terms provide us with a way to understand the inconceivable.

But understanding is the booby prize. How can anyone understand

the will of half a nation to cut down the other half in

a hundred days?

In

a scene when Dallaire is hauled up before a Belgian M.P.

and made accountable for the deaths of Belgian soldiers,

the west's complicit act of deliberate obfuscation becomes

the most morally unworthy act of the movie (in a genocide

this is saying something). It brought to mind Sigourney

Weaver's observations in Aliens when confronted

with a political team leader, Burke (played deliciously

by Paul Reiser). "You know Burke, I don't know which

species is worse. You don't see them fucking each other

over for a goddamn percentage!" The Belgian was playing

to the crowd, gaining political points while a good man

is smeared. They have a face to face but by then – to the

world's media – it's too late. Accuse a man of 'x' and the

'x' sticks regardless of his innocence. But then I am only

seeing this film's point of view. See how difficult the

truth is to mine? But we have the festering bodies as evidence,

the horror that turned man against neighbour. A sane, humanitarian

man would have stopped at nothing to prevent such a tragedy.

Nothing

was all Dallaire got in return for being a decent man in

a morass of indecency – both African and Western.

Originated

on 16x9 DV and various format sources of library material,

the film looks as good as can be expected and to the casual

viewer there is no remarkable downside to the 1.75:1 visuals

despite their obvious lack of quality (in our post modern

days, these images would look 'wrong' if they were perfect

in quality). The editor has chosen to add a slow motion

strobe on the actuality that makes things clear when mixing

Dallaire's re-visit and 1994's 'memories' via news bulletins.

The

Dolby 5.1 soundtrack really uses the surround element and

the sub woofer gets a few moments, mostly musical and one

utterly horrific. It is very clear that a great deal of

time has been taken in the mix. It is always clear – Dallaire

is a very good speaker and overall this aspect of the production

is particularly noteworthy.

Commentary

by Director Peter Raymont

Commentary by Toronto Star Critic, Geoff Prevere

There

are two commentaries and I have never encountered two for

one movie that were more polarized in style. The first is

by director Peter Raymont. His is laconic, respectful and

one must say, somewhat sparse. The second, by Toronto Star

critic, Geoff Pevere, offers us practically no pauses for

breath – it's extraordinary, almost as if he was told that

for every pause, he would receive an electric shock. This

relentless stream of comment is about as satisfying as the

other more laid back one mostly because you tend to zone

out at certain times because of their styles. With too many

words, you step back and I had a similar reaction to the

commentary of too few words. This isn't to say both are

not enlightening but both do cover ground the film has already

covered with more aplomb.

To

be fair, there are deliberate pauses in Pevere's commentary

– over the still living victims of the genocides near death

and pathetic in the true sense of the word and Dallaire's

take on the 'drunken' nature of genocidal violence but to

his credit, Pevere did describe his commentary as "babbling"!

Both reveal more about the men performing them than about

the film itself – that is not to be taken as a criticism.

Commentaries are points of views. Both men have such respect

for the film (based on the subject and effectiveness of

the storytelling of course) that in some way, they tiptoe

carefully as if a pensive Dallaire is in the room with them.

But Pevere does make a very good point, that Dallaire's

non-ironic ideals were so horribly ignored, perverted and

exterminated in Rwanda and that's what affects him deeply

(aside from the heavy cloak of guilt at being unable to

save lives).

Interview

with Director Peter Raymont (4x3, 7:43)

This touches on Raymont's relationship with his subject

and it's no surprise that Dallaire was treated very well

by the crew and he rewards them with a presence that has

integrity running out of every craggy pore. There isn't

a moment in the film where you think he's playing to the

camera.

Excerpt

Reading by Lt-General Roméo Dallaire

(4x3, 5:41)

All dressed up, medals displayed, this is Dallaire's video

address to the tenth anniversary memorials held in Kigali

in 2004. He reads two extracts from his book and both are

quite startling. He recalls meeting with the Interhamway,

the Hutu extremists who used mass media to kick start the

atrocities. There was still blood on one of their representative's

cuffs as they shook hands. Dallaire mentioned he had emptied

his gun before the meeting just in case he was moved to

shoot them all.

They

admitted that they were the perpetrators in a line that

sickens and repels. Out of respect of the U.N. and the character

of Dallaire, they agreed "not to massacre near U.N.

protected sites...", a practical admission of guilt.

It's a chilling memory. His second extract is more of a

coda summed up with the words that the 21st "must become

the century of humanity"... No luck so far.

Photo

Gallery

Chief Photographer Peter Bregg took pictures of Dallaire's

return to Rwanda and offers commentary on all 31 stills,

some family stories, some pertaining to Dallaire. An extraordinary

moment happens in his commentary over the schoolbook that

lays in a church were thousands were shot and hacked to

death and the bodies left to rot as a memorial to their

suffering. The recollection catches Bregg unawares and the

emotion comes through just for an instant. It's startlingly

moving.

This

is an important work for all sorts of reasons but aside

from alerting us to the horror we can inflict on one another,

it is also a character study of a man of conscience, goodness

and integrity. The fact he was a general in the U.N. is

heartening. Someone in power somewhere saw fit to give this

man a command. This is a good thing. They didn't see fit

to give him what he needed to do his job. In terms of lives

lost, this was a catastrophic thing. Shake Hands

With The Devil is a solid document of a singular

atrocity. I just hope that we can learn from its message.

|