|

Africa.

I

bet the first images that flood most minds are lions, vast

vistas of endless grasslands, maybe a red and white clothed

Maasai leaping up and down about to introduce Eastenders on the BBC. It always seems odd to me that such a vast continent

suffers from such a derisory public relations effort despite

having the tireless, crusading Bob Geldof on its side. Commandeered

as an enormous backdrop for the would-be Attenboroughs of

the rest of the world, Africa has been the wildlife wonder

of the planet since lenses were ground from the sands. Its

southern tenth has attracted the world's attention for rather

less than aesthetic reasons (that's if you don't include

Botswana and Alexander McCall Smith's rosy view of the country

via his Lady Detective Agency series of novels). The crux

of Africa's problems always seemed to come from miserably

grim, European intervention and rule. I'm reminded of the

sorry state the country is in by that neat little anti-missionary

aphorism: "When the white man arrived we owned the

land and they had the Bibles. They taught us to pray and

when we opened our eyes, we had the Bibles and they owned

the land." It would be interesting to speculate what

Africa would be now untouched by white bureaucracy, Christianity

and colonial rule. But there was no way that such a jewel

of a country would remain hidden, especially not from eyes

beady with visions of wealth and status. And this, I believe,

was one of the more insignificant reasons the genocidal

violence in Rwanda was so terrifying, so shocking. White

people seemed to have nothing to do with it (we can't blame

us). And after the violence erupted, we still wanted to

have nothing to do with it (we can shame us).

In Hotel Rwanda, Joachim Phoenix's cameraman

asks the obvious question: "What is the difference

between Hutus and Tutsis?" Or to boil the question

down to its fundamentals: why are Africans killing Africans?

The answer he gets is unsurprising if a little simplistic.

The original colonial Belgians divided up the populace by

employment and very broad physical characteristics. It's

generally believed that the Hutus are farmers and the Tutsis

a pastoral people. Physically, it seems, the Tutsis are

merely taller. Up until about 1980, a school of thought

known as Essentialism held sway in Rwanda - the belief that

you could not change what you were, what you were born to

be. Your very life was fixed. This and a profound lack of

basic education fuelled inter-continental racism until something

snapped. And something snapped loudly and horrifically in

Rwanda.

Working

in Africa (granted a mere decade ago), one quickly realised

that western ideals and practises are seen as curios in

a land where cocktails are served for the white tourist

elite, costing as much as the man or woman who serves it

earns in a month. Time operates in odd ways. Pre-arranged

appointments with officials are quite often breezily forgotten

or 'squeezed in' sometime in the working day. What Europe

and the US brought to Africa in the more enlightened period

of history (maybe Mandela's release could be the year things

started to get better) is proof that beyond a hand to mouth

existence there is a luxurious life to be had 'out there'.

The guy who drove me on a documentary recce in Tanzania

asked me to bring him back a Nikon camera (he went so far

as to have specified the lenses he wanted) and he wasn't

kidding, so deep the illusion of great white wealth is wedged

in the minds of the average African wage earner.

The

white man also brought the all too visible (but alas unaffordable)

trappings of an enviable lifestyle. In Hotel Rwanda,

small minded, violent men prize the smallest things we take

for granted. Most of the brutes portrayed in the movie are

appeased by the odd bottle of spirits, the crate of beer

("…for your men who must be very thirsty…").

But beyond that, the eccentricities of the Western culture

(and from an African perspective, they are hilarious eccentricities)

simply don't count here. What counts is raw power and that

usually means the biggest brute with a gun or machete. I

think I may have just stumbled on a parallel universality.

Surely Uncle Sam is the biggest brute with the biggest gun.

It's just in Africa, the violence is so immediate and not

cloaked in political rhetoric or justifications that would

make even Homer Simpson blush. I mean, did anyone see Bush

at a press conference a few weeks ago saying that Syria

really should move its troops out of Lebanon? I think I

actually barked hearing him say that. Light simply cannot

escape from the colour of Bush's pot.

There

is a sublime moment in Roger Spottiswood's Under

Fire. This particular genre could be called 'Hero

Journo in Dangerous Foreign Climes'. When a country destabilises

due to coups, insurrections or civil war, the threat of

meaningless and instant death is always around the corner.

It's the scariest threat of all because it is avoidable

IF you can outwit the brutes with guns, or IF you know exactly

the right thing to say. Your life is in your hands and minds

quite literally. Gene Hackman, watched by heroic photographer

Nick Nolte, blithely negotiates passage with a group of

rebels seen in a long shot. Hackman is an American. He is

even dressed in white. He is assured, confident and the

next second very dead in a terrible shock of realism in

a film that up to this point has certainly resonated but

not really caught fire. Hackman's superbly performed death

(like a marionette with its strings cut) slams Under

Fire into a third gear. NO ONE is safe. Films in

this genre trade on this never-ending presence of death

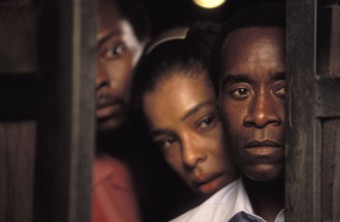

on a whim, a sort of Caligula-Effect. Hotel Rwanda falls into this genre despite the hero, Paul Rusesabagina,

being African. Paul is played with restraint and dignity

by American Don Cheadle, his African accent here a little

more convincing than his English Cockney in Ocean's

11 and 12.

Joachim Phoenix's character (news cameraman, Jack) expresses

very accurately what the rest of the world sees as Africa.

It's just that place where there are lions, where bad things

happen and we then return to our full Western plates and

push our snouts around the bounteous trough that is Western

culture. In some ways it's inevitable. People who have 'x',

have lived with 'x' all their life, take 'x' for granted.

'X' can be health care, food, water, civilisation and the

assumption that tomorrow morning all the Scots won't wake

up, hear of a plane crash, blame and then slaughter (with

machetes) all the Welsh - including the children (to stop

them from breeding). It is inconceivable.

It

IS inconceivable. It cannot be conceived. This is as alien

to us as an iPod must be to an African subsistence farmer.

It has been said that Rwanda's only hope is with the women.

If the men go on perpetuating the myth of inequality then

machetes and machine guns will continue to slash and spit

(whilst Hutu and Tutsi women mix and benignly compare methods

of child care). It's just that the hatred is so ingrained

it's almost like asking the Pope to denounce Catholicism.

Now there's an idea. It's not as if there are no precedents

(both Indian Hindus and Muslims were at each other’s

throats in 1947) but in Rwanda, it was like a fog of madness

had descended on the country and where there were once well

tended lawns in a prosperous Kigali street, there were now

corpses, slashed at and chopped down by a simple profoundly

lodged belief that 'If we don't kill them, they will kill

us…' To the more far-gone in terms of hatred, the

Tutsis were simply cockroaches, men, women and children;

disgusting things to be exterminated. It's tempting for

the west to regard Africa as '3rd world' or to use the euphemism

in vogue now 'a developing country'. But Africa is still

lodged in most western minds as a place where human life

is cheap (this has a ring of truth to it) but oh, the sunsets…

In

the middle of this escalating carnage is a mid-level hotel

manager trying to keep his family (he is Hutu, his wife

Tutsi) and innocents safe. As the situation worsens and

Tutsis are being killed on sight, the hotel becomes a haven

or ark for the displaced. Nick Nolte (again) plays Colonel

Oliver, a fiercely proud UN soldier whose job it is to keep

the peace - not maintain it indefinitely nor militarily

enforce it. Like the British soldiers in Bosnia, politically

forced to pull out of a region knowing that those they leave

behind will be slaughtered, Nolte is man torn by political

expediency and decent human values. His real relationship

with Paul is human and touching. They do not see skin colour

or nationality but respond to a situation as intelligent

men. Nolte's "You're dirt" speech is telling and

all the more horrific for being true. "You're worse

than niggers," he tells Cheadle, savagely parodying

the voice of his superiors' subtext in their orders to pull

out. "You're African."

Similarly,

Sabena's Belgian Flight Company President who runs Paul's

hotel from Europe is shocked to learn that his employees

are all about to be hacked to death. Extraordinarily, he

has enough clout to call off the attack on the hotel via

the French (whom the film states are giving the rebels the

arms they need). Played by Jean Reno, now moving into dignified

middle-aged roles (and sadly, middle aged roles in adverts

for DHL), the President offers Paul a lifeline. He's been

deftly manoeuvred into doing just that. Paul calls him up

to say good-bye as he will be slaughtered soon. That news

tends to make decent people act. When money is involved,

the world shifts. How dreadfully cynical is that? But Paul

knows this, exploits it, makes it work for him on a personal

level. Something that Hotel Rwanda explores

very well is the effort made by Paul to join the white elite,

to become (in his eyes) an efficient, civilised man whose

talents are prized in the wider world. It's a club his skin

will never let him join (the irony of a famous Hollywood

star with the same colour skin enjoying the west's best

on his days off is never far from the surface but all power

to Cheadle for taking the role on). The film underlines

his shock at being left behind as all the pasty skinned

tourists and religious helpers (yes, I admit, the clergy

are looking after the disadvantaged) are thrown out, some

reluctantly and some with great relief.

Directorially,

Terry George (much like Eastwood with Million

Dollar Baby) gets out of the way

and just tells the story. This is good simply because Hollywood

is a great medium (if the film is made well enough and not

cloying and righteous regarding its 'true story' origins)

for communicating injustice. It may have no tangible 'real-world'

result but at least someone can learn something by sitting

down and giving a few hours to one of mankind's most striking

acts of communal violence. The two elements that stop the

two thumbs piercing the atmosphere are the ending and the

music. Unwisely, it's scored very conventionally. This means

that just as you are gearing up- to be affected by these

awful images, the music steps in and says "Just in

case you don't get it, THIS IS TERRIBLE, feel baaaaad!" Hotel Rwanda needs none of this and mercifully

the instances the music pushes forward and becomes noticeable

are rare. Then we have the need for an ending and it's a

Hollywood doozy. Trouble is, it's true, albeit probably

time-shifted to serve as the climax of this solid and respectful

movie about one of Africa's darker periods. I can't complain. Hotel Rwanda is worthy film making in the

best tradition of that much-maligned term.

|