|

The Phantom Carriage has been simultaneously released in two DVD versions by Tartan – the one included here has a traditional instrumental score and is partnered with Ingmar Bergman's The Image Makers, while the single disc KTL Edition has a darker, more experimental musical accompaniment by the band KTL. The transfer is identical on both discs, but the very different scores on each do havean impact on how you view the film. My review of the KTL edition does cover the qualities that are specific to both versions in enough detail to not need repeated or re-emphasising here. To read that review follow this link.

With the same transfer used for both discs, the comments made regarding the picture on the KTL Edition also apply to this version.

The soundtrack is a different matter. The instrumental score included here was written by Swedish composer Matti Bye, previously responsible for creating a new soundtrack for the 2002 re-issue of the 1916 silent Dödskyssen (aka Kiss of Death), which was co-directed by The Phantom Carriage's Victor Sjöström. A traditional silent movie score in every sense, it mirrors the varying moods of scenes using instruments that would have been available to musicians at the time of the film's initial release. It may not have the immediate impact and stand-alone appeal of the KTL score, but is also more varied in tone and does not cast every sequence in a sinister light.

Mastered in PCM stereo 2.0, the quality of the recording is first rate, having a fine clarity and tonal range. There's a lot less bass than on the KTL soundtrack, but violins, pianos and harps are not as famed for their lower frequency work as synthesisers.

KTL Edition (5:56)

Four extracts from the simultaneously released KTL Edition are usefully included for direct comparison, though all contain imagery as creepy as the accompanying score. The fourth is the sequence, mentioned in a footnote to my KTL Edition review, that bears a striking similarity to a famous scene in The Shining.

The Image Makers [Bildmakarna] is a made-for-TV adaptation of the 1992 play by Per Olov Enquist and the penultimate moving image work of the then 82-year-old Ingmar Bergman. Inspired by a meeting between Victor Sjöström (the director and lead player of the The Phantom Carriage) and Selma Lagerlöf (the widely respected author of the novel on which it is based), it was clearly a work dear to Bergman's heart. The Phantom Carriage was apparently one of his favourite films, and in the late 1990s he directed a production of Enquist's play for the Royal Dramatic Theatre of Sweden that was greeted with acclaim both on home turf and on its cross-Atlantic trip to New York.

The version here could be seen as an opportunity taken to record that stage show for posterity, given that it also features the same cast (and believe me, that itself would be no bad thing), but despite the one-room set and carefully orchestrated entrances and exits of individual characters, this is no simple record of performance, but a compelling piece of television theatre in its own right. Performance and script driven, as such a piece should always be, it is nonetheless as subtly cinematic as many of the director's theatrical features, and shows Bergman to be as comfortable with the medium of television as he has repeatedly proved himself to be with cinema.

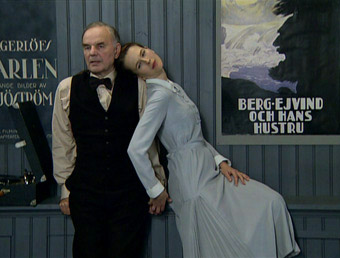

The meeting at the heart of Enquist's play and Bergman's film takes place in a small screening room at the studio at which The Phantom Carriage is being produced. Director Victor Sjöström and cinematographer Julius Jaenzon are nervously awaiting the arrival of ageing, Nobel prize-wining author Selma Lagerlöf to show her clips of their film version of her work. Both men are intimidated by her reputation and status – the one person who is not is stage actress Tora Teje, a brash, beautiful and seemingly self-assured young woman who flirts with Julius but has been having an affair with Victor.

The first meeting between Selma and Tora is deceptively cordial. The writer walks into the screening room just as Tora is reading her work aloud, a recitation that Selma describes simply as "beautiful." But almost from the moment they meet there is a curious if largely one-sided tension between them, with Tora quickly adopting an adversarial stance, her initially too-loud and too-enthusiastic responses seriously winding up Victor. His impatient and persistent requests for her to leave are on the verge of being granted when Selma unexpectedly requests that she stay. From this moment on, the room becomes a battleground of opinion and personality clash, Selma's behavioural advice to Tora sparking an angry response from the actress, who loudly refuses to be intimidated by Selma's presence and verbally assaults Victor for his poor judgement and for "tinkering" with writing that she deeply admires.

That a bond begins to develop between the two women is to be expected, but it's a constantly surprising journey that bristles with sudden and explosive conflict. Seemingly very different in personality and background, the pair discover that they have more in common than suggested by their first contact, and it's in the peeling back of their surface layers that the play and film are at their most powerful and perceptive.

Not being a Swedish speaker, I have to take the accuracy of the English subtitles on trust, but so good is the English prose that if those responsible are being creative with the original then their talents are being wasted. The sometimes electrifying banter between Tora and Selma intermittently pauses for eloquent and revealing monologues, caught in unbroken close-up by Bergman's unobtrusive but always perfectly placed camera. Individual lines are priceless in their suggestive economy: "What did I say?" asks Selma in mild bemusement after Tora's first blow-up, "I've only just got here," to which Tora replies bitterly, "No, you've been here for ages – your spirit has been here for weeks," while Tora herself is later tellingly told by Victor, "You don't know the meaning of fear, and that makes you frightening."

Excellent though Lennart Hjulström and Carl Magnus Delloware are as Victor and Julius, it's the two women who rightly steal the show. As Tora and Selma respectively, Elin Klinga and veteran actress Anita Björk make a thrilling double-act, with Klinga's supercharged, expressive energy balanced by Björk's controlled and knowing restraint, the impetuous passion of youth in collision with the experience and tolerance of old age.

The Image Makers is TV theatre as it should be, preserving the structure and dialogue of its stage original but taking full advantage of the presentation opportunities offered by television. Magnificently played by a superb quartet of actors, it may also prompt you, as it did me, to re-watch Sjöström's The Phantom Carriage in a different light, more aware of the personal relevance of its story to the creative talents at its core.

Made for Swedish television and shot on digital video, the picture quality is consistently excellent. Contrast, colour and sharpness are all just right, and the transfer doesn't have that video look of pre-digital studio-based TV works but pleasingly appears not to have been run through a film-look filter. The framing is 4:3, as it was recorded and originally broadcast.

The Dolby 2.0 mono soundtrack presents the dialogue clearly and that's all that it's asked to do. The optional English subtitles are very clear.

None.

As I said in my coverage of The Phantom Carriage – KTL Edition, if you're looking to watch the film in the spirit in which it was made and originally shown, then the version here is probably the one to go for. It comes recommended anyway for its pairing with The Image Makers, Bergman's penultimate film and a splendid example of how good television theatre can be when the right actors are paired with the right material and a director who understands the unique advantages of the medium rather than seeing it as secondary to cinema.

|