|

This is the third of four Blu-ray box sets, eight feature films per set, to be released by the BFI, which break down Ingmar Bergman’s long and prolific career roughly by decade. By the end of the 1940s, Bergman was establishing himself first as a writer and then as a director, but had only just been allowed by Svensk Filmindustri (henceforward SF), for whom he had worked most often for, to make films from his own scripts. By the end of the following decade, he had established his reputation worldwide, doing so in a very rich period for cinema in languages other than English and had made some of his greatest works, including two shot in the space of less than a year, The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries. Bergman was beginning a lengthy purple patch – about a decade and a half, but one studded with films his reputation will stand on. The 1970s and the part of the 1980s which marked his final decade as a cinema director, were for various reasons more uncertain, more uneven. But that will be for Volume 4 to cover. Volume 3 takes us through the 1960s and what are remarkable are not as much the films included in this third set but also some of the ones not included. In previous reviews, I’ll briefly cover the films not in the set as I get to them chronologically, though for this disc I’ll deviate from this towards the end of this review.

Following The Face, the next project Bergman’s took to SF was The Virgin Spring. Concerned by the grim subject matter, SF asked him to make a more commercial film, a comedy, in return for their backing the darker project, and the result was The Devil’s Eye (Djävulens öga). Although Bergman was sole screenwriter, the film is based on a radio play, The Return of Don Juan, by Oluf Bang.

The film begins with a caption from what purports to be an Irish proverb, that a woman’s chastity is a stye in the Devil’s eye. And now Satan (Stig Järrell) has just such a source of discomfort – a twenty-year-old vicar’s daughter Britt-Marie (Bibi Andersson), a virgin if engaged to be married. Satan fears that her example may cause more young women to hold on to their virginity so liberates Don Juan (Jarl Kulle) from his infernal punishment and sends him to Earth to seduce Britt-Marie.

In 1994, BBC2 showed a short season called Bergman’s Women. Okay, you had an opportunity to see some of Bergman’s least well-known and least-shown feature films. Or, looked at another way, you were offered a season of his comedies minus the one that most people thought was any good, namely Smiles of a Summer Night. While Bergman in 1960, let alone 1994, was regarded as one of the cinema’s great dramatists and tragedians, comedy was certainly not his forte. Bergman may be in more playful mood than normal, but there’s definitely something heavy-handed about his work here, and try as he might it simply isn’t especially funny, despite the best efforts of several of his regular cast. While it’s not Bergman’s worst venture into the lighter side, it simply lacks that vital spark.

The Devil’s Eye brought one of Bergman’s long-standing professional relationships to an end. It is the last of his films to have been shot by Gunnar Fischer, who had contributed immeasurably to the look of many of the films Bergman’s reputation had been built on. Bergman and Fischer fell out during the film’s production, with the result that with his next film, Bergman began his second – and longer – great partnership with a cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, with whom he had previously worked on Sawdust and Tinsel. Fischer continued his long career elsewhere, though it’s fair to say that nothing he made since had the same impact, internationally at least, as his work for Bergman. He died in 2011 at the age of one hundred.

The Devil’s Eye was released before the film Bergman made after it, The Virgin Spring, on 17 October 1960 in Sweden. After a showing at the Edinburgh Film Festival in August 1961, it went on UK release in 1963. Given the extensive list of rival titles, some of them also directed by Bergman, it didn’t trouble any award body and was from the outset regarded as very much a minor work. That it undoubtedly is, though as with anything Bergman wrote or directed or both, there’s plenty there for aficionados.

Sweden, the Middle Ages. Fourteen-year-old Karin (Bigitta Pettersson) is sent by her father Per Töre (Max von Sydow) to take candles to the church. As this is a journey of more than a day, she is accompanied by servant Ingeri (Gunnel Lindblom), who is pregnant with the father unknown and is a secret worshipper of Odin in this Christian society. However, all changes when Karin meets three young men, who turn upon her...

It hadn’t been until 1949, with Prison, Bergman’s sixth feature as director, that he had been allowed to both write an original screenplay and to direct it. Once that Rubicon had been crossed, Bergman rarely looked back. It’s worth noting that The Virgin Spring is the second of just two cinema films after that point in which Bergman had no writing credit on. Both of those films were written by Ulla Isaksson. Bergman had called upon her services three films earlier, with Brink of Life, based on her novel. No doubt Bergman felt himself rather out of depth with the film’s subject matter, a study of three women from different backgrounds and circumstances, in a obstetrics/gynaecology ward. Bergman had certainly had experience of fatherhood by then, but only as a father, and not a good one by his own admission. Maybe the difficult storyline of The Virgin Spring made him want the insurance of a female screenwriter? (Those two Bergman films in his later career which he directed but didn’t write became three with his 1975 version of Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, made for television but also released theatrically. Two more followed later in his career once he had retired from directing for cinema but still did so occasionally for television: The Blessed Ones (De två saliga, 1986), again written by Isaksson from one of her own novels) and The Image Makers (Bildmakarna, 2000), from a play by Per-Oluv Enquist, about the inception and making of the classic Swedish silent The Phantom Carriage, which had been directed by Victor Sjöström, whom Bergman had regarded as a mentor for decades.)

Another influence may have been Kurosawa’s Rashomon, which had had a considerable impact when it was shown in the West a decade earlier. With that film we have four perspectives on a rape and murder in the woods, four witness reports on one event. That event is also a rape and murder, and it’s up to ourselves to work out what “really” happened. Such playing with truth and history is not Bergman and Isaksson’s concern. For Töre, the impetus is to find out what had happened – the one thing, in the one interpretation – and to act upon it. And he does.

Returning to the Middle Ages again after The Seventh Seal, Bergman and Isaksson use the storyline – derived from a thirteenth-century Swedish ballad to explore themes of religious faith, Christianity versus pagan worship. Guilt hangs heavily on all the main characters – for not being there when Karin was being attacked, raped and then murdered, and in Töre’s case particularly for harbouring incestuous desires towards his own daughter. And while the urge for vengeance may well be understandable, what price our humanity if we go down that road?

I’ve mentioned before that many of Bergman’s earliest films did not get wide releases in the West because of a possible mismatch between what we can see and hear and what the American or British censors would then allow. We might get a brief nude scene, or dialogue containing sexual references that went beyond the level of explicitness local audiences would expect. The coming of the X certificate in the UK (then, restricted to sixteens and over) allowed much more of Bergman’s work to be released, both new ones and older films belatedly released due to his fame. However, come the 1960s, some of Bergman’s films were testing boundaries again, and cuts were made to The Virgin Spring in both the UK and the USA to tone down some details of the rape scene. (The film is now uncut, with the original BBFC X certificate now a 15.)

That The Virgin Spring was regarded as a serious work of the cinematic arts, and not some kind of exploitation film, was not in doubt. Quite a lot has been made of The Virgin Spring as a template for the rape-revenge films which peaked in the 1970s, to some discomfort as that what would bracket Bergman, one of the cinema’s major highbrow auteurs, with what was frequently seen as irredeemable trash for grindhouse audiences. (More about that in the commentary.) Yet there is a direct link: Wes Craven more or less remade the film, setting in the USA as The Last House On the Left.

The Virgin Spring was released in Sweden on 31 March 1960, and played in competition at Cannes in May of the same year. It gained a Special Mention and won the FIPRESCI Prize, but that year’s Palme d’Or was Fellini’s La dolce vita. However, The Virgin Spring did win the Golden Globe for Best Foreign-Language Film, plus the Oscar in the same category, Bergman’s first win of the latter. The film also picked up an Academy Award nomination for Marik Vos’s black and white production design.

The popular view of Ingmar Bergman, of a dour angst-merchant forever plying his dark worldview via characters spending the running time debating God and the Devil and tearing each other apart, is an enduring one. It ignores the humanity and humour in his work, even if when he does make an out-and-out comedy the results are more often than not unsuccessful. Yet if that popular image endures, that may well be due to the films Bergman made next, his “Faith Trilogy”, which comprised Through a Glass Darkly (Såsom i en spegel, 1961), and, both from 1963, Winter Light (Nattvardsgästerna) and The Silence (Tystnaden). And in particular the first of these. From its premise alone, it seems like parody Bergman. Robert McKee, author of Story, is often blamed for a plague of formulaic three-act screenplays coming out of Hollywood, is much more wide-ranging than he is always given credit for. Bergman is one of McKee’s screenwriting heroes, and the climactic scene in Through a Glass Darkly is one of the examples he uses.

The Faith Trilogy can be watched in any order, as each film is entirely separate. There are however overlaps in the cast and certainly the crew, with Sven Nykvist having rapidly made himself a vital part of it. Through a Glass Darkly was shot on the island of Fårö, in the Baltic Sea just north of the larger island of Gotland. Bergman was so taken by the location that he shot several more films on the island, and also lived there. You wonder how different Bergman’s life and filmography might have been if he had gone with his original location choice, namely Orkney.

Through a Glass Darkly is a sparse film, with four principal characters and no one else to be seen, and the story takes place over twenty-four hours. Karin (Harriet Andersson) has spent time in an institution following a diagnosis of schizophrenia. She is staying on a remote island with her husband Martin (Max von Sydow), a doctor, and Karin’s father David (Gunnar Björnstrand), a novelist suffering from writer’s block. Also with them is Karin’s teenaged younger brother Minus (Lars Passgård). The interrelationships between the four are complex and not always honourable: having been told by Martin that Karin is incurable, David has been noting her symptoms and behaviour, as if to jumpstart his own stalled creativity. Minus is dealing with his own sexual coming of age. Karin, hearing voices from behind the peeling attic wallpaper, expects God to make an appearance from there...

As well as paring down the visuals, Bergman did the same with the soundtrack, with the exception of some brief moments of cello music. Bergman and Nykvist considered making the film their first colour production, but were dissatisfied with the tests they shot. Andersson declined the film at first, thinking her role too challenging, to which his reply was “Don’t give me that load of shit!” Their relationship with Bergman was long over: he was now married to Käbi Laretei, to whom the film is dedicated. Her performance here earned her a BAFTA nomination, for Best Foreign Actress (Anne Bancroft won for The Miracle Worker).

Released in Sweden on 16 October 1961, Through a Glass Darkly also showed in competition at the 1962 Berlin Film Festival, where it won the OCIC Award (given by the International Catholic Organization for Cinema and Audiovisual), though the Golden Bear was won by A Kind of Loving. Along with Andersson’s nomination, the film was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Film from Any Source, which it lost to Lawrence of Arabia. Meanwhile, Through a Glass Darkly earned Bergman his second nomination for Best Original Screenplay and it won him his second consecutive award for Best Foreign-Language Film.

The second of the trilogy, Winter Light (Nattvardsgästerna), followed Through a Glass Darkly into cinemas a year and a half later. It can be watched entirely separately from its predecessor, although both films have Gunnar Björnstrand and Max von Sydow in principal roles, and there’s at least one brief call-back to the former film’s imagery, namely God being a spider-like entity. As a middle film, Winter Light has tended to fall by the wayside a little, compared to the multi-awarded Through a Glass Darkly, and the what would provide to be a cause célèbre (or maybe succès de scandale) of the final film, The Silence. However, it was Bergman’s own favourite of the three.

Tomas Ericsson (Björnstrand) is the pastor of a remote village, widowed for five years and feeling that his role is more and more irrelevant. His services are poorly attended, one of whom is schoolteacher Märta Lundberg (Ingrid Thulin), who is also his mistress. Another parishioner, Karin (Gunnel Lindblom) asks him to help her husband Jonas (von Sydow) who is in despair due to the world’s arms race and fears nuclear apocalypse. If God is present, Tomas thinks, he is slow to show Himself and Tomas is close to giving up waiting.

Many of Bergman’s films of his peak period are concise, but at 80 minutes, Winter Light is one of the most so, pared down to not much more than essentials. (Not for nothing did some critics mention Robert Bresson – a much older and much less prolific director who was breaking through at the time.) The film is set in cold, miserable winter weather, and that seems somehow to have leaked into the very celluloid. Björnstrand was genuinely unwell during the making of the film. The film was a development of Bergman’s relationship with Sven Nykvist. Normally, Bergman would make films in the summer and theatre in the winter, but in this case he and Nykvist were after a flat, grey, low-contrast light, with one scene lit only by candlelight. Björnstrand may have the lead role, but Thulin delivers a tour de force when Märta writes a letter to Tomas, which Bergman stages by having Thulin read to camera, in one eight-minute take. Winter Light had its own making-of, Ingmar Bergman Makes a Movie (Ingmar Bergman gör en film), originally shown on Swedish television in five episodes in 1963. The director was Vilgot Sjöman, soon to become a director in his own right, sometimes controversially, with 491 (1964, which incidentally hired Gunnar Fischer as cinematographer) and the much-censored diptych I am Curious (Yellow) (Jag är nyfiken – gul, 1967) and I am Curious (Blue) (w, 1968).

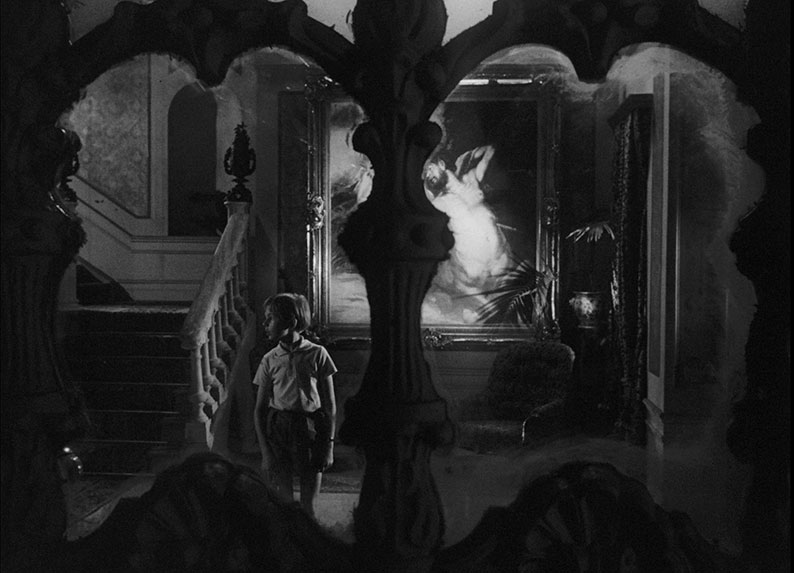

Bergman entered the film industry well into the sound era, but his mentors included Alf Sjöberg and Victor Sjöstrom, men of an earlier generation who had achieved mastery in silent cinema. Bergman began as a writer, although his abilities as a director soon caught up, and as part of a general paring-away and concision were occasional attempts to do without dialogue as much as possible. Even a minor film like Dreams (1955) has a long sequence almost entirely without spoken dialogue. The Silence (Tystnaden) doesn’t eschew dialogue in the same way, but it has a noticeably sparse dialogue script. Bergman reckoned it had between thirty-four and thirty-eight lines of dialogue, depending on your definition, though he adds that if he had had more discipline he’d had removed around ten of them. Communication, or the lack of it, is a vital theme, especially given that the three principal characters are in a city where none of them speak the local language. The Silence may be the third in the Faith Trilogy, but it looks forward to his next-but-one feature, Persona.

Two sisters, Ester (Ingrid Thulin) and Anna (Gunnel Lindblom), and Anna’s ten-year-old son Johan (Jörgen Lindström), are on a train journey late at night. They decide to stop over in Timoka, a town in a Central European country on the brink of war...and one where which none of the three – and Anna is a professional translator – can speak the local language. Ester is ill, getting through it with vodka and cigarettes.

The Silence is one of Bergman’s more difficult films. In it, Bergman has created another world, a particularly hermetic one. So it can seem that we are looking at these three characters from outside and try as we might we can’t find a way in. With the sparse dialogue comes a greater use of lengthy and intricate camera movements. As Ester remains sick in bed and Anna continues to care for her, young Johan takes to wandering around the hotel. When Anna goes out, a waiter makes advances on her. She goes to the theatre, and is both repelled and fascinated by a man and a woman seemingly having sex in a nearby seat.

That scene moves us beyond what Bergman had shown us in recent films, beyond many other directors in fact, and this caused Bergman to run up against censorship overseas. While the edits which had been made to The Virgin Spring had all been visual (the rape and, to some respect, the revenge), in The Silence some visual material was toned down, other edits were made to the dialogue. In a subtitled film, this simply means a retranslation and a toning-down of the dialogue, and unless you are fluent in Swedish, you would be none the wiser. This boundary-pushing didn’t hurt the film’s box-office – in fact, the film was a commercial success.

Cornelius (Jarl Kulle), a music critic, arrives at the large estate of the celebrated cellist Felix, to write his biography. Yet Felix is barely there – and a brief glimpse of him with what Cornelius takes to be his wife, is corrected by Felix’s actual wife Adelaide (Eva Dahlbeck) who says that her husband has several lovers, and the chief of them is “Bumblebee” (Harriet Andersson), who immediately has sex with Cornelius...

After three films delving into such weighty subject matter as the Faith Trilogy had done, and about to go on to do, Ingmar Bergman could certainly be excused for wanting to kick back a little. That’s fine in practice, but not so much in reality. While it’s certainly untrue that Bergman had no sense of humour, and was clearly able to incorporate humorous sequences into otherwise serious work. However, if you make Smiles of a Summer Night the great exception that it is, Bergman’s comedies linger amongst his minor work. All These Women (För att inte tala om alla dessa kvinnor, also known as Now About These Women...), cowritten by Erland Josephson, is a contender for his worst. That said, Bergman was always happy for the film to be shown, unlike his 1950 film This Can’t Happen Here (Sånt händer inte här), which is only available at the time of writing as a VHS-quality online rip. That had been Bergman’s eighth feature as director. By now, he had made seventeen more, and All These Women isn’t negligible for craft reasons.

Bergman and Nykvist had considered shooting Through a Glass Darkly in colour, but had been unsatisfied with the test results. So All These Women became Bergman’s first. It was something of a one-off as his next four feature films are all in black and white. The results aren’t what you might expect. Bergman and Nykvist don’t go for the saturated prime colours that a Hollywood epic might have done, but a more muted, sometimes pastel palette. The opening shot, held for some three minutes, sets the tone: an arrangement in black, silver and grey, with flesh tones added to the mix when people start appearing on screen.

The delicate touch that Bergman brought to Smiles of a Summer Night is wholly missing here. All These Women takes its cue from stage farce of a particularly heavy-handed kind and the results are close to unwatchable. Given his productivity over the last decade, Bergman entered something of a hiatus. it would be two years before the world saw another Ingmar Bergman feature film, but instead of a failure we had one of his greatest works.

There’s a game you can play, for which you’ll need access to online runs of magazines and newspapers. Which great films (or if not great ones, very good ones, cult movies, or at least ones of significant interest) opened on the same day as each other, or were in cinemas at the same time? Let’s say it’s 21 September 1967 and you’re in London. Which films do you want to see today? Bearing in mind you have to be over sixteen given their X certificates, you could see the new Ingmar Bergman at the Academy in Oxford Street and the new Robert Aldrich at what was then called the Warner West End. But did anyone actually go to see both Persona and The Dirty Dozen on their opening night? (And if you didn’t fancy those two, also opening in London that day were the new Roger Corman and the new Peter Yates, The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and Robbery respectively.)

But if that was you, watching Persona on its opening day, with little information to hand (other than the reviews you might have read), it’s clear from the moment the film begins that something has changed. We're back in black and white. A light appears in the darkness: a carbon arc striking, film going through a projector, the leader countdown. Images flash up on the screen: four frames of an erect penis (removed at the time for censorship reasons, later restored, of which more below), part of a silent film comedy with the projector whirring on the soundtrack (actually part of the pastiche silent that featured in Bergman’s earlier Prison), a crucifixion with a nail being hammered into a hand, a spider, a sheep slaughtering. Part of the purpose of this sequence is to reinforce the idea that the viewer is watching a film, a construct, and Bergman will insert further Brechtian alienation effects as the film goes on. Some of the images are references back to his earlier work: that silent comedy for one, but also that vision of God as a spider from Through a Glass Darkly, but now in closeup instead of simply being referred to. A young boy (Jörgen Lindström, himself a reference back to The Silence, though he’s uncredited this time) reaches out towards the image of a woman on a screen…

After this prologue, the film proper begins. Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann), an actress, suddenly falls silent on stage. Suspected of having had a breakdown, she is put in the care of a nurse, Alma (Bibi Andersson). When no progress is made, Alma and Elisabet spend time in a remote cottage by the seaside. As the days pass, Alma tries to break Elisabet’s silence, but soon becomes unsure of her own identity…

Persona was mostly shot on Fårö, and is a two-hander with a total credited cast of four. As with The Silence, Bergman counterpoints sound and silence: Alma’s volubility versus Elisabet’s mutism. All this plays out on Fårö’s landscape, which Bergman and Nykvist make an abstract space for this drama.

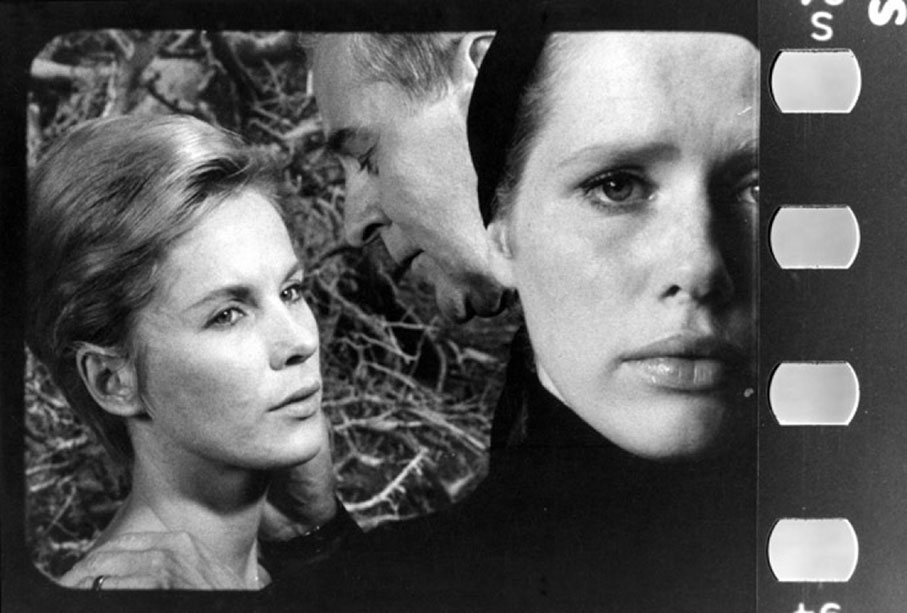

The film is a tour-de-force for the two leads. Bibi Andersson had worked for Bergman before, but in smaller roles. She had had a relationship with him, though that had ended at the end of the previous decade. She has almost all of the film's dialogue, including an extraordinary scene where she relates a sexual encounter with some boys on a beach, revealing much of herself to the silent woman sitting opposite. (Although the script is credited to Bergman solo, Andersson contributed to this monologue, making some changes to it along the lines of what she felt a woman would more likely say.) Persona was Liv Ullmann's first film for Bergman, and it was a significant one as they entered a relationship and later had a daughter together. It's a remarkable performance, relying almost entirely on her face. She speaks a total of fourteen words throughout the film. Bergman is one of the great exponents of the close-up and there are many examples in this film, as if it is possible to use what is an external photographic medium to uncover his characters' souls. The gap between her public face (persona) and her private one is at the core of Elisabet's breakdown, and is at the heart of Alma too. And finally, the two women's faces visually merge.

This is a film from a particular moment in a decade of change. This comes home to us as the external world intrudes on Elisabet as she recoils in horror from then-contemporary television footage of the Vietnam War, with a Tibetan monk setting himself on fire. With this film, Bergman took on techniques which were then moving out of the avant-garde into the wider artistic world, as at several times he makes us aware that this film is not reality, but a construct, beginning with the prologue and credit sequence mentioned above. More than once the fourth wall is being broken, with Bergman framing Andersson and Ullmann so that they speak to camera. Towards the end, we see the camera crew. At one key point, halfway through, the film “breaks” and burns up. If Persona began with the projector striking up, it ends with the film coming out of the projector onto a reel. This deconstruction also extended to the film's publicity as original publicity stills were reproduced with the frame's sprocket holes in view.

If you look at many of the contemporary reactions to Persona, you can – understandably – more than a little puzzlement, with some critics putting Bergman back in their informal international-auteur rankings. (It’s easy to forget that this was a very rich period for world cinema, with many major names in the prime of their careers.) Yet others, for example Susan Sontag in a six-page essay for Sight & Sound (Autumn 1967, before the film had arrived in the UK) were calling it a masterpiece from the outset.

The film rapidly settled in as one of Bergman's greatest works, and within only a few years one that had entered the culture sufficiently that references to it would be quickly understood. Jean-Luc Godard parodied Alma's monologue near the start of Weekend. Longtime Bergman devotee Woody Allen sent up one of the film's most famous shots (you’ll know which one already, but just in case, a very tight combination of profile and close-up) in Love and Death. Before that, William Friedkin had lifted the same shot near the end of The Boys in the Band, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the identity-blurring with the aid of mirrors was among the ferment of ideas and images behind Performance. You can see Persona's influence in films like Two-Lane Blacktop (which also has the trope of film “burning” in the projector) and Mulholland Drive.

Yet there was more. In 2002, it was noticed that the version of Persona which had played widely in the West for over thirty-five years by then was incomplete, due to censorship of the time. A flash-image (four frames) of an erect penis was restored to the prologue. Also, it turned out that Alma’s monologue had been toned down in translation, though granted you would have had to be fluent in Swedish to notice.

In 2012, Persona placed seventeenth in Sight & Sound's all-time best poll. (As I write this, the results of the 2022 poll are awaited.) Persona is not the easiest of Bergman's films to get to grips with, but it's a compelling, disturbing, brilliantly acted work, rewarding many viewings. A truly great film.

Persona would be a high-water mark to end this box set and this review, but due to the logistics of the release, there is one film remaining. In these reviews so far, I’ve included details – a paragraph or so – of Bergman’s films not included in these sets, where they would appear chronologically. I’m going to deviate from this, just the once, so as to make the final part of this four-part review a more coherent look at the final decade and a half of Bergman’s cinematic career. So, details of Bergman’s films of 1967 and 1968 (the portmanteau film Stimulantia and the features Hour of the Wolf (Vargtimmen) and Shame (Skammen)) will be in my review of Volume Four. Then Bergman made another film for Swedish television, which had a theatrical release overseas.

The majority of of Bergman’s career was in the cinema and on stage – at peak productivity, he’d make a film usually in the summer and a theatre production in the winter. However, he worked in other media as well, radio being one. During his particularly prolific year of 1957, he found time to make Mr. Sleeman is Coming (Herr Sleeman kommer), a 43-minute production of a 1917 one-act play by Hjalmar Bergman (no relation), broadcast, presumably live, on 18 April 1957 on Swedish television. For the next decade, Bergman made the occasional television production, which have almost all slipped into obscurity (presuming they still exist): The Venetian (1958), Rabies (1958), Storm Weather (1960), A Dream Play (1963) and Dom Juan (1965).

The Rite (Riten) was different. The Rite was a full-length feature, if on the shorter side at an hour and a quarter. It had a credited cast of four (plus Bergman as a priest) and was shot on film by Sven Nykvist, though given the intended medium and possibly also to reduce costs, it was on 16mm rather than 35mm. (Black and white, still, but most of Europe did not have colour television when The Rite was first broadcast. Colour began officially in Sweden in 1970.) Viewers overseas, where The Rite had a small cinema release, might have been forgiven for not noticing much obvious difference between this and Bergman’s more chamber-style cinema features. That was especially the case as, increasingly rarely in Western Europe, Bergman was able to continue to make his cinema productions in black and white and in Academy Ratio, so The Rite would have looked little different. Maybe the status of The Rite as a hybrid work gave Bergman the idea of producing similar work for both media. And so he went on to do, producing three more “novelistic” serials for television, which were released in shorter versions in cinemas: Scenes from a Marriage (Scener ur ett äktenskap), Face to Face (Ansikte mot ansikte) and his farewell to cinema directing, Fanny and Alexander (Fanny och Alexander). The first and last of these will be released in the BFI’s fourth box set.

Judge Abrahamson (Erik Hell) is hearing the case of a theatre company accused of putting on an obscene performance. The company comprises two men, Hans (Gunnar Björnstrand) and Sebastian (Anders Ek) and a woman, Thea (Ingrid Thulin). Sebastian drinks and is in debt; he killed his former partner and is now having an affair with Thea, the partner’s widow, who is married to the new troupe leader Hans.

The Rite tackles a theme that was increasingly current in later-1960s culture: censorship and its break down. Bergman had played his part in this, particularly with The Silence, and The Rite pushes at a few boundaries – verbal ones and those involving nudity – in its turn. Yet it is not as one-sided as it may seem, with the failings of the artists laid bare, just as much as those of the would-be authoritarian.

You have to wonder how liberal Swedish television was at the time, or maybe it was the case that because Bergman was a recognised name worldwide, he had greater licence. But even so, I can’t think of other countries’ television channels who would have broadcast this unedited at the time. This isn’t just due to frankness of dialogue (which, as we’ve seen, could be toned down in translation) but also of costume design. By the end of the film, those worn by Hans and Ek include large phalluses and Thea’s makes her topless. The Rite is a dense, not always easy to grasp film, and you have to imagine what television audiences would have made of it. On its joint Swedish/Norwegian premiere, on 25 March 1969, the play was preceded by a conversation between Bergman and television and theatre director Lars Löfgren, Bergman suggested that the audience would be better off going to the cinema instead. The Rite played in British cinemas in July 1971, and you may wonder if the BBFC’s revision of their certificates the previous year had had an effect, allowing the film to be passed uncut given that the X certificate was now eighteen and over rather than sixteen and over.

This is the third of what will be four Blu-ray box sets released by the BFI, comprising eight films each. There are five discs, all encoded for Region B only, two films per disc for the first three, one each for the last two, in the order above.

The box set has a 15 certificate. All the feature films except Winter Light carried X certificates on their original UK cinema releases. The Devil’s Eye and All These Women are now PG. Winter Light also has that rating, having originally had an A certificate. The other five films are now rated 15, all uncut.

The first seven films, all made for cinema release, were shot in black and white 35mm, except for All These Women, in Eastmancolour 35mm. All are presented in 1080p at twenty-four frames per second, as you would expect for sound films for cinema release. They are restored at 2K resolution from the original camera negative (The Devil’s Eye, The Virgin Spring, Winter Light, Persona) or interpositive (the others). All are correctly framed in Academy Ratio, 1.37:1. While most of the Western world had gone widescreen by the mid-1950s, Bergman was able to continue using the old Academy Ratio for a decade and a half more. Certainly in the UK, and probably other Western countries, Bergman’s films (being in a foreign language with subtitles) would play in arthouse and repertory cinemas which usually could still show the ratio which was now commercially obsolete. The Academy in Oxford Street, London, where many of Bergman’s films premiered, certainly could: it frequently held long runs of such Academy classics as Les enfants du paradis and The Seven Samurai well into the 1980s. The transfers are fine, with contrast and greyscale as they should be. The Devil’s Eye is darker and more contrasty, though this may reflect Fischer’s cinematic style as opposed to Nykvist’s. The one colour film is, as described above, more intentionally muted than with intentionally saturated primary colours.

The Rite, shot in black and white 16mm as mentioned above, was supplied by the Swedish Film Institute in Standard Definition. Rather oddly, my player tells me the transfer is still 1920x1080 at 24 frames a second, so it has been upscaled at cinema speed, rather than the Swedish PAL television broadcast speed of twenty-five. I don’t know which is correct: twenty-four may indeed be the case given that the film was also intended for cinema release as well as television broadcast. The transfer is in 1.33:1, which is certainly the ratio you’d expect for a television production of its time, slightly narrower than Academy. I have no issues with the transfer itself, which is a little grainier than the other transfers, but that’s to be expected. We’re also watching on less forgiving equipment than Swedish television sets from 1969.

The soundtrack is the original mono in all cases, clear and well balanced and with the dialogue easily audible. English subtitles are available as an option and a default on all eight films and on the The Men and Bergman documentary. They are fixed on the three short introductions to the Faith Trilogy. The Virgin Spring was released in the UK in both subtitled and dubbed versions, but only the subtitled one is available here. I don’t know if that was due to the distributor sensing a possibly wider audience due to controversy, and I also don’t know if that was successful or not.

Audio commentary on The Virgin Spring by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Josh Nelson

It’s about five or so minutes into this commentary that Josh Nelson addresses a particular elephant in the room. Alexandra Heller-Nicholas is an authority on the subject of rape-revenge films and in fact has written a book on the subject, Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study, which saw a second edition in 2021. Indeed, the subject takes up much of the commentary so Heller-Nicholas inevitably dominates, but there’s plenty to engage with here. At one point, she cites Linda Ruth Williams regarding ideological grounds for the proportions of rape and revenge in given films. In this case, the rape happens at the halfway point so you could say it’s an equal emphasis.

Stills galleries

On the appropriate discs are self-navigating stills galleries for The Virgin Spring (3:00), All These Women (4:42) and Persona (5:12). (The booklet, or at least the PDF copy of it sent for review, erroneously says that they are available for The Silence and overlooks All These Women.) These are pretty much as you would expect, though Bergman-now-in-colour was not sufficient a draw to enable many colour stills for All These Women: all but a few are in black and white.

Ingmar Bergman Introductions to the Faith Trilogy

Marie Nyreröd drives Bergman to his office and viewing theatre (which will be familiar to anyone who has seen Mia Hansen-Løve’s 2021 film Bergman Island) and he gives a brief introduction to each of the Faith Trilogy, though given the running times (1:52, 3:38, 3:35 respectively) nothing in-depth. They speak in Swedish and the English subtitles are fixed.

BFI Screen Epiphanies: Richard Ayoade Introduces Persona (11:51)

Recorded at the BFI Southbank in 2011, Ayoade, in conversation with Eddie Berg, gives an appreciation of Persona, which begins with the acting but also encompasses Bergman’s staging. Some of this, including some of the most famous shots, was “found” while shooting was taken place as Bergman had allowed for reshoots and second thoughts. While Ayoade’s admiration for Bergman knows no bounds, he hesitates to compare himself to him, even when Berg invites him to do so regarding his first film Submarine.

Trailer for Persona (2:38)

A US trailer (with the aspect ratio cropped to 1.85:1) gets a philosophical voiceover, with critics’ quotes left as text captions at the end.

The Men and Bergman (51:59)

Sharing a disc with The Rite, this is a companion piece to The Women and Bergman, which can be found in Volume 2. Both produced and directed by Eva Beling in 2007, they follow much the same format as each other. Nils Petter Sundgren interviews three actors who had worked regularly with Bergman: Börje Ahlstedt, Thommy Berggren and Thorsten Flinck. In addition, he interviews Erland Josephson at his home. As with the women’s film, it’s a shame that some of Bergman's major collaborators aren’t present – presumably unavailable if still with us – but the result is heavy on the anecdotes and inevitably less on personal feelings.

Booklet

Eight more essays, again with spoiler warnings. This booklet is available in the first pressing only.

Kat Ellinger kicks off with The Devil’s Eye, which is an interesting contrast to her commentary on Volume Two for The Seventh Seal, from one of the big beasts of Bergman’s filmography to what is usually thought of as a minor work. Yet Ellinger uses both to make the point of Bergman’s humanity, and sense of humour, far away from his reputation as a purveyor of dour Scandinavian doom and gloom. In The Devil’s Eye he gets to show his playful side, though again “man wastes time talking to a God who doesn’t listen”.

Catherine Wheatley’s piece on The Virgin Spring is inevitably very different, and begins by comparing Bergman’s film with another from the same year, which killed off its purported leading lady halfway through. Wheatley also brings the legend of Little Red Riding Hood into her analysis.

Claire Marie Healy talks about Through a Glass Darkly as a change from the period/historical films which made Bergman’s reputation, to something new. Healy also discusses the influence of Bergman’s then (and fourth) wife Käbi Laterai, who was a concert pianist. Through her, Bergman was inspired to incorporate musical ideas in his screenplays. If Through a Glass Darkly is a chamber film, it’s also chamber music, a string quartet with each of the principal characters one of the quartet. Healy also discusses Karin’s mental illness, in the terms understood by the medical profession of the time.

Winter Light is discussed by Jannike Åhlund. By 1961, when Bergman was making this film, he was continuing to direct for the stage, and had become artistic director of Svensk Filmindustri, while turning down a lucrative offer from MGM. The autobiographical overtones Tomas has are clear enough from earlier script drafts where he is referred to as “I” or “I.B”. Åhlund also discusses some technical aspects, particularly Nykvist’s cinematography and Ingrid Thulin’s eight-minute speech to camera. Bergman gave a copy of the latter to Thulin’s husband as a fiftieth-birthday present.

Philip Kemp takes up The Silence, unpicking the title’s several meanings, not least the silence of God, but also the lack of communication between the three principals and everyone else. The local language, which we hear now and again and read on a newspaper, was made up by Bergman, borrowing from Finno-Ugric languages, in particular Estonian, which Käbi Laterai spoke. With the relative dearth of dialogue, Bergman and Nykvist’s camera became a lot more mobile. Kemp also discusses the film’s contribution to the breakdown of censorship in its home country, with the Swedish censor after some deliberation passing the film uncut.

Ellen Cheshire takes a hostage to fortune in her essay on All These Women by beginning with “Ingmar has no sense of humour”, something Bergman’s family told him at a young age. In his autobiography, Bergman does talk about three of his own comedies, but these are Smiles of a Summer Night, The Magic Flute and Fanny and Alexander, but skips over others, including this one. It’s either the short straw, or a challenge, to produce an essay on a film that almost no one rates amongst Bergman’s work, and from the outset Cheshire refers to the various mistresses of Felix (six of them) as caricatures. She has to search hard even for some less-unfavourable reviews. Her essay didn’t change my opinion that this film is a barely-mitigated disaster, but she does find something of worth in it.

Geoff Andrew, who has turned up several times before in the BFI’s Bergman releases, tackles Persona, and does a thorough job in discussing what he (and I) think is one of the greatest films ever made – less so because many of its themes are so characteristic of Bergman’s mature period, but because it was so radically innovative as well. An excellent piece on a film which stands up to countless viewings.

Finally, Andrew Graves talks about The Rite. He begins by citing Bergman’s biography The Magic Lantern and sees the film as a means to his confronting his own fears and shortcomings by means of those of the characters.

Also in the booklet are full credits for the films, notes on and credits for the extras, and stills.

Ingmar Bergman Volume 3 shows the director consolidating his position as one of the pre-eminent figures in world cinema in the 1960s, though not without a couple of misfires. They are all well presented in this Blu-ray set.

|